Translate this page into:

Awareness and Attitude of Select Professionals toward Euthanasia in Delhi, India

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

The topic of euthanasia has induced differences not only among professionals in the medical fraternity but also in other fields as well. The dying process is being lengthened by the new state of art technologies erupting as such higher pace, and it is at the expense of standard quality of life and of a gracious death.

Aim:

To study the awareness and attitude toward euthanasia among select professionals in Delhi.

Methodology:

It was a questionnaire-based descriptive cross-sectional study. The study population included doctors, nurses, judges, lawyers, journalist, and social activists of Delhi. Tool included a sociodemographic questionnaire, two questions to know awareness regarding euthanasia and a modified euthanasia attitude scale used to measure attitude toward euthanasia. Data were analyzed using Stata 11.2.

Results:

Through our study, it is evident that professionals who participated in the study (judges, advocates, doctors, nurses, journalists, and social activists) in Delhi were familiar with the term euthanasia. No significant difference was seen in the attitude of professionals of different age group and sex toward euthanasia.

Conclusion:

Through this study, it is found that judiciary group most strongly endorsed euthanasia. The attitude of doctors was elicited from mixed group with doctors belonging to different specialties. Oncologists are not in favor of any form of euthanasia. However, doctors from other specialties did support euthanasia.

Keywords

Attitude

Euthanasia

Letting die

Mercy killing

Palliative care

INTRODUCTION

The topic of euthanasia has induced differences not only among professionals in the medical fraternity but also in other fields as well.[1] The word euthanasia is a mix of two ancient Greek words, “thantos” and “eu” where word “thantos” stands for death and word “eu” stands for good. Hence, the word euthanasia means to end life in a painless way. The incongruity over euthanasia has generated different definitions. Some interpret it identical with terms such as “good death” while others understand it as disgraceful.[12] There is another approach with regard to euthanasia that evokes the concepts of voluntary versus involuntary euthanasia. Voluntary euthanasia refers to the patient's voluntarily request to end his or her life, whereas involuntary euthanasia refers to euthanasia decided upon by the health-care provider without any patient request and involves a patient who may or may not have the capacity to express such an opinion.[12]

The dying process is being lengthened by the new state of art technologies erupting at such higher pace, and it is at the expense of standard quality of life and of a gracious death. Physicians frequently administer therapies against the wishes of the patient as life-prolonging treatments. The patients may stress upon their right to take part in decisions which are related to their life.[34]

The wide-ranging opinion for and against euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide (PAS) have made the arguments more distinguished, understated, and urbane. The crucial claims such as opinions based on patients’ sovereignty to regulate their own lives and kindness in relieving agonizing pain and suffering have persisted remarkably the same since the late 19th century debates about euthanasia. However, the present-day arguments have laid significant and exceptional practical research, enlightening many facets of euthanasia and PAS.[1] Independent assessment of the prevailing work and day-to-day practice in a lot of countries demonstrates that substantial variances exist in opinions among patients, doctors, politicians, and lawyers on the subject of end-of-life decisions such as forgoing therapy, do not resuscitate orders, withdrawal of therapy.[1]

Intensive care medicine faces massive challenges with regard to end-of-life decisions such as withdrawal of therapy as it is now possible to continue life for elongated periods without any hope of recovery. Care to confirm the comfort of a dying patient is as vital as the prior attempts to achieve cure.[5]

To avoid confusion of terminology, practice of withholding or withdrawing life-supportive cares should be guided by a thorough understanding of the goal.[6] A large number of cases around the world have discovered the boundaries of present legal differences, drawn between legitimate and nonlegitimate occasions of putting end to life.[7] According to the Dutch euthanasia act, if a physician performs euthanasia or PAS, his/her actions will not be punishable. The physician has been convinced that[7] there is a voluntary and well-considered request from the patient,[8] the patient is suffering unbearably without prospect of improvement,[9] the patient has been informed about his/her situation and prospects,[10] there are no reasonable alternatives to relieve suffering, an independent physician must be consulted, and[3] euthanasia or PAS is performed with due medical care and attention.[11]

Most of the times request for euthanasia arises on three occasions.[1]

-

At birth

-

At the terminal stage

-

When a person is severely compromised due to brain damage (unexpected accident).

At the time of birth

When a physically and mentally handicapped infant is born decision to end life lies with the parents or the doctors supported by the law of the land.[3] In the Netherlands, neonatal and infant deaths preceded by the intentional administration of life-shortening drugs are known to take place although rarely.[5]

At terminal stage

When the patient is at the terminal stage.[12]

Unexpected accident

When a person suffers from hypoxic brain damage from where it cannot recuperate regardless of the treatment given and patient's life can be continued only by artificial means in a state of suspended animation. These incidents evoke our thought process that whether the treatment which is being given is prolonging life or death. In such instances, whether he/she may be allowed to die in comfort and with dignity.

The objective of the present study is to study awareness and attitude toward euthanasia among select professionals in Delhi.

METHODOLOGY

It was a questionnaire-based descriptive cross-sectional study carried out between April and August 2013. The study population included doctors, nurses, judges, lawyers, journalists, and social activists of Delhi.

Nonprobability convenience sampling was done. Tools included a sociodemographic questionnaire, two questions to gauze awareness and the euthanasia attitude scale (EAS) which has 30-statements which are measured on Likert-scale. Questionnaire developed by Holloway, Hayslip, and Murdock, 1995, to gauge attitude toward euthanasia were used. The EAS has both positively worded statements which are 16 in number and negatively worded statements which are 14 in number. The responses are collected on the following scale, namely, definitely agree, agree, disagree, and definitely disagree. To quantify the statements, numbers that range from four to one were given to the positive statement. Numbers for the negative statements were reversed. The total score is derived from the sum of both positive and negative statements. The total score ranges between 30 and 120. The scores between 75 and 120 indicated an endorsement of euthanasia and the scores <75 indicated a negative attitude toward euthanasia. The questionnaire was circulated among the study population to measure the clarity and adequacy of the questions. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was derived, and the value of Cronbach's alpha was calculated as 0.82 in the pilot study in a suitable sample of 30. Data were analyzed using Stata 11.2 (Data analysis was done by the Department of Biostatics, AIIMS) and all the P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Relationship of categorical variables among the groups was compared using Chi-square/Fisher's exact test. Student's t-test was used to compare mean values in the two independent groups, and one-way ANOVA was used for more than two groups.

RESULTS

Three hundred questionnaires were returned out of 460, giving a response rate of 65%. All the respondents were aware of the term euthanasia. Fifty percent of the responders comprehend euthanasia as mercy killing, and around 40% understood euthanasia as PAS [Table 1].

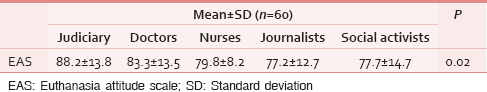

As evident in Table 1, the mean of the total scores for the EAS was statistically significant (P = 0.02). There was a significant difference (P = 0.02) among selected professionals (judiciary, doctors, nurses, social activists, and journalists).

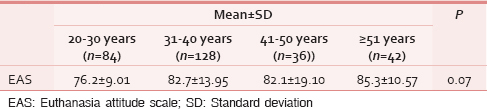

As noted in Table 2, there was no significant difference seen in the attitude of the professionals in different age groups toward euthanasia (P = 0.07) using one-way analysis although professional with more than 51 years of age were found to robustly endorse for euthanasia.

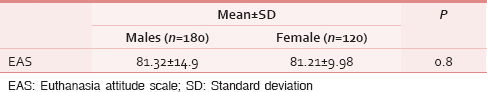

As shown in Table 3, there was no significant difference observed in the attitude of professional groups between the two genders toward euthanasia (P = 0.8).

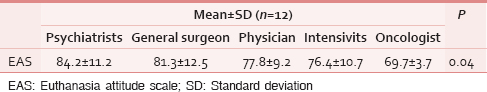

The mean of the total scores for the EAS was statistically significant (P = 0.04) among doctors. There was a significant difference (P = 0.04) among selected doctors (psychiatrist, physician, general surgeon, intensivist, and oncologist) [Table 4].

Seventy-seven percent of journalist, 68% of the nurses, and 62% of social activists believe that no action should be taken to persuade death even if death is superior to life in a terminally ill patient, whereas 77% of the judiciary and 60% of the doctors disagree with the same (P = 0.02). Seventy-seven percent of judiciary, 80% of the doctors, 60% of the journalists, and 58% of the social activists back the practice of comfort procedures only and allow dying in peace without further life-lengthening treatment, whereas more than 50% of the nurses are against the view (P = 0.02). Over 80% of the judiciary, doctors, journalists, and social activists are against keeping a brain dead person alive with proper medical care (P = 0.01). Eighty percent doctors, 77% of judiciary, 72% of the nurses, and 57% of the social activities share the view that a person with a terminal and painful disease should have the right to refuse/reject life-sustaining/support treatment; however, journalist do not hold the same view (P = 0.03).

Eighty-six percent of judiciary, 70% of the doctors, 68% of the nurses, and 57% of the social activists are of the opinion that there should be no ill feelings toward a person, who hastens the death of a loved one to spare them from further unbearable pain; however, journalists do not corroborate with the above opinion (P = 0.04).

Eighty-two percent of the judiciary, 60% of the doctors, and 59% nurses are of the view that there should be legal avenues by which an individual could preauthorize his/her own death, should intolerable illnesses arise, whereas journalists and social activists do not conform with the same (P = 0.13).

Eighty-one percent judiciary, 75% doctors, 64% of the nurses, more than 50% of the journalists, and 50% social activists endorses that terminally ill person in severe pain deserves the right to have his/her life ended in the easiest way possible (P = 0.09). About 75% doctors, 71% social activists, 59% judiciary, and 52% journalists support a doctor's decision to reject extraordinary measures if a patient has no chance of survival; however, 55% of the nurses disagree with it (P = 0.20).

Eighty percent of the doctors, 76% of the social activists, 71% of journalists, and over 50% of the nurses believe that the administration of a lethal dose of some drug to a person in to prevent him from dying an unbearably painful death is unethical although judiciary does not corroborate with the same (P = 0.01). Majority of the professionals swerve with the view that person who assists a suffering, terminally ill person to die is nothing but a common murderer. About 77% of the nurses, 52% of journalists, and 29% of the social activists oppose the view of inducing death for merciful reasons, whereas 50% of the doctors and judiciary agree with this view (P = 0.03). Nearly, 77% nurses and 52% journalist are against forceful parenteral feeding for terminally ill patients, judiciary and doctors are equivocal in their views, 72% social activists are supportive of it in our study (P = 0.03). Fifty-five percent of the nurses are of the opinion that the termination of a person's life, done as an act of mercy, is unacceptable to them, whereas 68% judiciary, 60% doctors, and 57% of journalists differ with this view (P = 0.50).

DISCUSSION

The study was primarily conducted in one city, i.e. Delhi. It was conducted in one of the cities; hence, result cannot be replicated nationwide. Heterogeneity was sought as much as possible in the composition of the study sample. A standardized validated instrument EAS was used to measure the attitude toward euthanasia. This questionnaire was modified to the Indian setting. A pilot study was done, and internal consistency of the questionnaire was calculated the value of Cronbach's alpha was 0.82.

Through our study, it is evident that professionals who participated in the study including judges, advocates, doctors, nurses, journalists, and social activists in Delhi were familiar with the term euthanasia. The reason of this familiarity could be because judiciary including other professionals has spent enormous time over the issue.[7]

No significant difference is seen in the attitude of professionals of different age group toward euthanasia. However, older professionals, i.e., >51 years of age were found to support euthanasia more strongly. Our findings are similar to one of the studies where no difference is found in the attitude of doctors of different age group.[13]

No association was found between gender and attitude toward euthanasia in our study. The results of our study are similar to the Canadian teaching hospital study where no difference in attitude among doctors of different age groups and gender were found although they looked at only one group of professionals, unlike our study.[14] Similarly, no significant correlation between attitude of elderly people toward euthanasia and variables such as gender were found.[3]

Findings of our study are in resonance with the study done among Polish physicians, nurses, and people in which it is found that group of population, who have no professional experience with the terminally ill are in favor of euthanasia.[15]

All the respondents except for judiciary considered the injection of a lethal dose of some drug to a person to prevent that patient from dying an unbearably painful death unethical. Opinion of professionals on euthanasia varies widely between countries.[5] In one of the studies, it was found that legislators and jurisdictions of several countries (France, Scotland, England, South Australia, and New Hampshire) voted against legalizing euthanasia and PAS and have opted to improve palliative care services and to educate health professionals and the public.[161718] Moreover, opinion of legalizing euthanasia is not common among doctors who are more experienced in end-of-life care, more frequently trained in palliative care.[171819]

Probably one of the reasons for these findings were that legislators and jurisdictions of several countries felt that legalizing euthanasia and assisted suicide had placed many people at risk, affected the values of society over time, and had not provided controls and safeguards.[18]

Outcome of our study with regard to euthanasia among doctor population is in consonance with the study conducted among physicians of Washington State where it is evident that hematologists and oncologists were against euthanasia and assisted suicide as they had the most exposure to terminally ill patients. However, psychiatrists were the strongest supporters of the two practices as they had the least contact with terminally ill patients. One explanation for these findings may be that many hematologists and oncologists believe that more effective use of available treatments to relieve pain and suffering would prevent the need for euthanasia and assisted suicide.[20] In another study, it is found that if training in end-of-life care and the ability of doctors to give palliative care is improved a request for euthanasia and PAS are likely to lessen.[5]

In our study, judiciary, doctors, journalists, and social activists support the practice of comfort measures only and allow dying in peace without further life-prolonging treatment, whereas more than 50% of the nurses are against this view. This could be interpreted as complex attitude of the nurses toward euthanasia, as in our study; on one hand, the nurses supported palliative care and on the other hand they are of the view that life-supporting treatments should not be withheld. In one of the studies related to complex attitude of the nurses toward euthanasia, it is found that complexity arises because of the needs of nurses at the level of clinical practice, communication, emotions, decision making, and ethics.[7]

Judiciary, doctors, and nurses strongly support patient's choice and their rights. They believe that terminally ill patients should have the right to end their life, and to reject any life-sustaining/support/additional/extraordinary treatment. They are of the view that there should be legal possibilities by which an individual could choose to make advance directives, which allow the individuals to express and document their treatment preferences at the time when they are competent and to inform health-care professionals how they would like to be treated in case of incompetency.[914]

It was opined that allowing euthanasia may also lead to unethical practices in public life with respect to elderly who should or may receive definitive care and unscrupulous caregivers may opt for euthanasia on unethical grounds.

CONCLUSION

The judiciary group most strongly endorsed euthanasia. The attitude of doctors was elicited from mixed group with doctors belonging to different specialties. About 20% of doctors were oncologist and none of them endorsed euthanasia. It must also be noted that none of the doctors had any experience in palliative care. This could both indirectly inform and create a different attitude in favor of euthanasia compared to the group of oncologists, who are the most closely involved in treating terminally ill patients. The study also indirectly suggests that not only awareness about euthanasia but also the pros and cons of it in terms of alternative modes of treatment/care that are available currently needs to be made more aware to the public, especially those professionals such as judiciary, social, and journalists involved in addressing human beings and quality of life.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: A review of the empirical data from the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:142-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Canadian physicians and euthanasia: 2. Definitions and distinctions. CMAJ. 1993;148:1463-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes towards euthanasia among health workers, students and family members of patients in hospice in North-Eastern Poland. Prog Health Sci. 2012;2:81-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes and practices of U.S. oncologists regarding euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:527-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitude of the macedonian intensivists regarding withdrawal of therapy in intensive care patients: Curriculum for policy development. Med Arh. 2011;65:339-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Euthanasia, assisted suicide, and the philosophical anthropology of Karol Wojtyla. Christ Bioeth. 2001;7:379-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2004. Attitudes of the Elderly Towards Euthanasia: A Cross Cultural Study. Available from: http://www.etd.uovs.ac.za/ETD-db/theses/available/etd./RAMABELET.pdf

- Opinions of health care professionals and the public after eight years of euthanasia legislation in the Netherlands: A mixed methods approach. Palliat Med. 2013;27:273-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review article euthanasia [mercy killing] 2008. J Indian Acad Forensic. 30:92-5. Available from: http://www.medind.nic.in/jal/t08/i2/jalt08i2p92.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes toward euthanasia of physician members of the Italian Society for Palliative Care. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:907-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preferences for receiving information among frail older adults and their informal caregivers: A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2012;29:742-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes towards euthanasia and assisted suicide: A comparison between psychiatrists and other physicians. Bioethics. 2013;27:402-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes toward euthanasia among Polish physicians, nurses and people who have no professional experience with the terminally ill. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;788:407-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Should euthanasia be legal? An international survey of neonatal intensive care units staff. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F19-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Legalizing euthanasia or assisted suicide: The illusion of safeguards and controls. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:e38-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abortion and euthanasia of Down's syndrome children – The parents’ view. J Med Ethics. 1983;9:152-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes toward assisted suicide and euthanasia among physicians in Washington State. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:89-94.

- [Google Scholar]