Translate this page into:

Creation of Minimum Standard Tool for Palliative Care in India and Self-evaluation of Palliative Care Programs Using It

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

It is important to ensure that minimum standards for palliative care based on available resources are clearly defined and achieved.

Aims:

(1) Creation of minimum National Standards for Palliative Care for India. (2) Development of a tool for self-evaluation of palliative care organizations. (3) Evaluation of the tool in India. In 2006, Pallium India assembled a working group at the national level to develop minimum standards. The standards were to be evaluated by palliative care services in the country.

Materials and Methods:

The working group prepared a “standards” document, which had two parts – the first composed of eight “essential” components and the second, 22 “desirable” components. The working group sent the document to 86 hospice and palliative care providers nationwide, requesting them to self-evaluate their palliative care services based on the standards document, on a modified Likert scale.

Results:

Forty-nine (57%) palliative care organizations responded, and their self-evaluation of services based on the standards tool was analyzed. The majority of the palliative care providers met most of the standards identified as essential by the working group. A variable percentage of organizations had satisfied the desirable components of the standards.

Conclusions:

We demonstrated that the “standards tool” could be applied effectively in practice for self-evaluation of quality of palliative care services.

Keywords

Audit

Developing countries

Hospice care

India

Limited resources

National standards

Palliative care

Quality assurance

Quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Two and a half million people live with cancer at any given time in India. At least 2.47 million people live with HIV/AIDS, and more than a million people suffer from pain that could be controlled with adequate medication. Only a small minority of those with cancer or HIV have access to palliative care.[12] In this context, it is imperative to evaluate existing palliative care services.

Wherever palliative care is beginning to take root, palliative care enthusiasts work hard to achieve coverage. In our attempt to reach as many of the needy as possible, there is the danger that services will be spread too thin and reduce quality of care. Establishment of national standards for palliative care will pave the way for improvement in quality of palliative care delivery. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that “in low-resource settings it is important to ensure that minimum standards for pain relief and palliative care are progressively adopted at all levels of care in targeted areas, and that there is high coverage of patients through services provided mainly by home-based care” (pg 91).[3] More than 30 countries, mostly in the developed world, have adopted such standards. Unfortunately, very few reports in literature document the development of these hospice or palliative care standards or surveys of the outcomes of standards auditing.

The development of national hospice and palliative care associations and related standards of program operation has evolved over the past 35 years from the first hospice standards adopted by the National Hospice Organization in the United States in 1979.[45] National datasets have been developed to describe hospice services,[6] and a schema to describe levels of palliative care development has been developed.[78] The development of national standards for palliative care is an essential step in each country's palliative care development.

Auditing of health care services is also an important activity that needs monitoring.[9101112] Standards can be audited to measure the degree of compliance for individual providers.

The following were the objectives of the study:

-

Creation of minimum National standards for Palliative Care for India

-

Development of a tool for self-evaluation of palliative care organizations

-

Evaluation of the tool in India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In 2006, Pallium India, a non-Government organization, assembled a working group to develop palliative care standards. Its objective was to draft National Palliative Care Standards for India. Invitations were sent to 18 representatives including non-professional palliative care activists, nurses, and doctors from around the country. Thirteen accepted and were included in the working group.

After numerous emails and a face-to-face meeting, the group decided to establish some benchmarks to assist palliative care practitioners to evaluate their services. The results would indicate strengths, weaknesses, and areas that needed improvement. The group decided to prepare a standardized form to measure the following seven domains of care:

-

Structure and processes of care

-

Training of personnel

-

Physical, psychosocial, and spiritual dimensions

-

Drug availability

-

Ethical and legal aspects

-

Organizational aspects

-

Quality.

The face-to-face discussion and email dialog, which followed, eventually resulted in a draft “standards” document. With funding from the U.S. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), a working group met at Rajagiri College, Kochi on February 7, 2008 for another face-to-face discussion and finalized a standards document. It had two parts–the first composed of eight “essential” factors and the second composed of a group of “desirable” factors. This document was presented to the 400 odd participants of the annual conference of the Indian Association of Palliative Care on February 8, 2008. The participants’ comments were noted, and the working group met again to consider the recommendations and modify the document. The final document with 28 items is given in Appendix 1. The Indian Association for Palliative Care (IAPC) has considered adoption of these standards by the Association.

Between February and June 2008, the working group sent the document to 86 hospice and palliative care providers nationwide, whose addresses or other contact details could be traced. They were requested to self-evaluate their palliative care services based on the standards document on a modified Likert scale.

Respondents were asked to email their results to NHPCO. Forty-nine palliative care agencies responded, giving a 57% response rate. The SAS software was used to generate statistical reports.

Each response was assigned one of the following values:

-

Never = 0 point

-

Rarely = 1 point

-

Sometimes = 2 points

-

Often = 3 points

-

Always = 4 points.

A mean score was calculated by summing up the points for each question and dividing the sum by the total number of respondents. The lowest possible score was 0.00 and the highest possible score was 4.00.

RESULTS

Demographics

Provider type

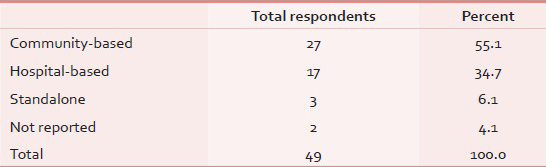

Analysis of responses identified the following provider types: Community-based, Hospital-based, Standalone, and Other. The majority of respondents identified themselves as community-based providers, 34.7% were hospital-based and 6.1% identified themselves as standalone providers [Table 1].

Provider size

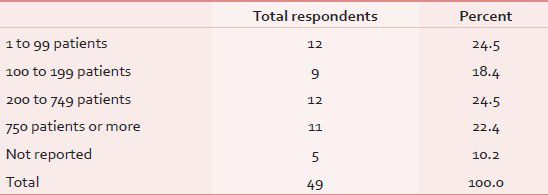

Most providers handled a large volume of patients. The majority were programs that served more than 200 patients per year. The number of patients served varied widely. The smallest program had a census of 46 patients, and the largest had approximately 6,000 patient contacts per year [Table 2].

Overall use of essential palliative care components

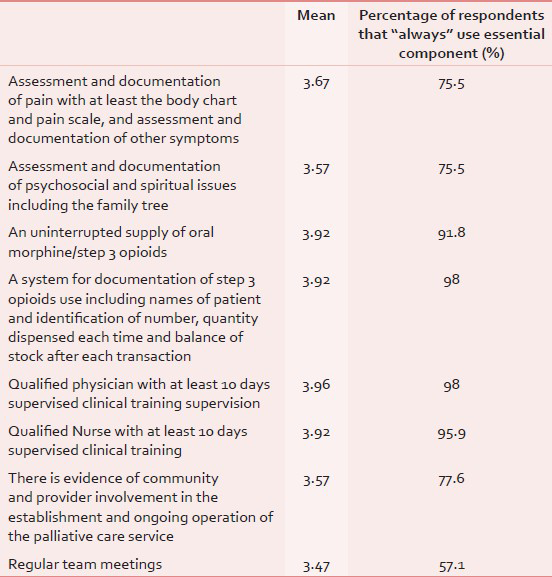

The hospices and palliative care providers met most of the standards identified as “essential” by the working group. Almost all providers had a system to document the use of step 3 opioids and had the services of a trained physician and nurse. Not all programs had “regular team meetings,” suggesting that providers needed to improve communications between team members [Table 3].

Core modules for palliative care (Desirable Standards in Italics)

Clinical care

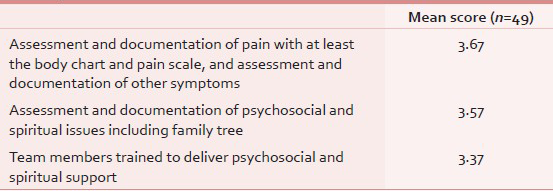

A palliative care service should have in place a system for assessment, documentation, and management of patients that includes at minimum the three items in Table 4.

The responses indicate that all the measures for quality care are being met most of the time by most respondents. Assessment and documentation of pain with at least the body chart and pain scale and assessment and documentation of other symptoms scored the highest. (Mean = 3.67). Training of team members to deliver psychosocial and spiritual support scored the lowest.

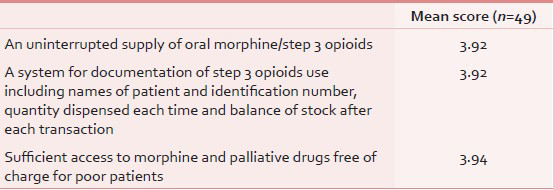

Availability of palliative care medicines

A palliative care service should provide access to essential medications as demonstrated by the three items in Table 5.

All three measures, both essential and desirable, scored very high, suggesting that for responding programs, opioids and other palliative medicines are readily available at all times, properly documented, and free of charge to patients unable to pay for them.

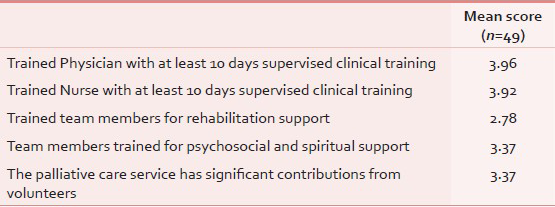

Staffing

A palliative service should adopt a team approach. It should at least have the items in Table 6. Essential staffing components scored higher than aspirational components. The weakest area was trained team members for rehabilitation support (Mean = 2.78).

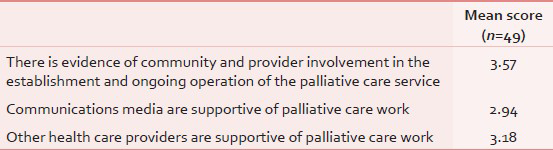

Community and health care provider relations

A palliative care service engages the community and does not work in isolation.

Scores for the community and health care provider relations module indicated the need for improvement. Although there is evidence of community and provider involvement in the establishment and ongoing operation of palliative care services, the essential component of this module scored higher than the desirable components (Mean = 3.57). There is room to improve relationships with the communications media (Mean = 2.94) [Table 7].

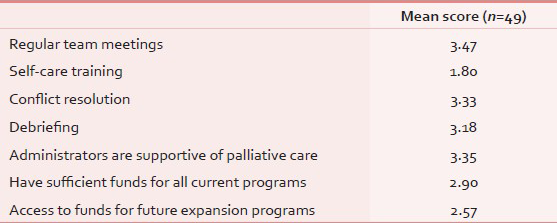

Organizational health

A palliative care service supports the health of the team through the activities described in Table 8. Organizational health could also be improved. Regular team meetings, the only essential component in this module, scored the lowest of all the essential components (Mean = 3.47). Of all the aspirational components, self-care training for staff scored lowest (Mean = 1.80) suggesting a great need in this area.

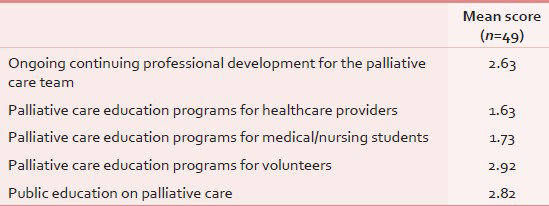

Education

A palliative care service has an education and training program that includes the items in Table 9. The essential measure scored a mean of 2.63, indicating a need for ongoing professional development for the palliative care team. The aspirational measures scored highest for availability of education programs for volunteers. Educational opportunities for healthcare providers (Mean = 1.63), medical and nursing students (Mean = 1.73) needed improvement.

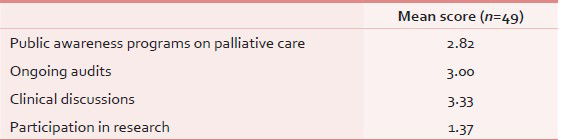

Quality improvement

A palliative care service is committed to continuous quality improvement. Although the quality modules comprised only aspirational measures, they scored well in comparison with the other modules. Most organizations reported clinical discussions and ongoing audits, although these were not always fully integrated. However, “participation in research” scored the lowest of all measures in the survey with a mean of 1.37 [Table 10].

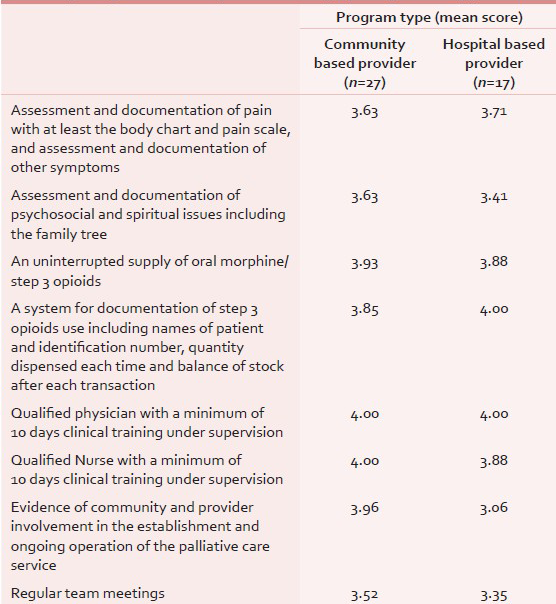

Results by program type

Essential components

The survey demonstrated that standard measures varied according to provider type. Community-based providers reported “always” more often on all the essential measures than hospital-based providers, except for assessment and documentation of pain and a system of documentation of step 3 opioids, including names of patient and identification number, quantity dispensed each time, and balance of stock after each transaction [Table 11].

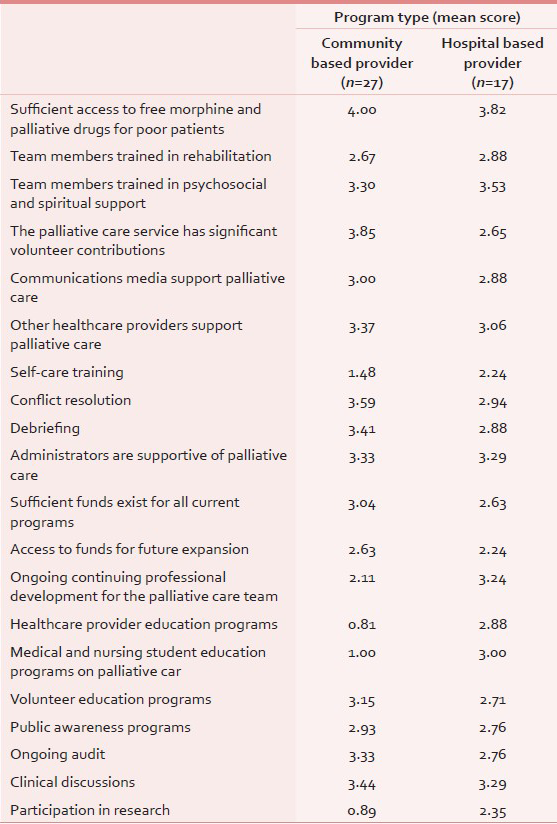

Desirable components

Hospital-based providers scored higher than community-based providers in the domains of professional development, research, and staff self-care [Table 12].

Essential components

The larger programs with more than 750 patients per year had better systems in place for documentation of pain and other symptoms (Q1). Smaller programs reported greater community support (Q7).

Aspirational components

With regard to aspirational components, the larger programs scored highest on availability of funds, professional staff development, and participation in research. The smaller programs reported better organizational health. They scored higher on support from volunteers and administrators, conflict resolution, and debriefing. Interestingly, the smaller programs also scored higher for ongoing audits.

With regard to drug availability, the larger programs that serve more than 750 patients per year were the only ones to report that they did not always have sufficient access to free morphine and palliative drugs for poor patients, when all three other categories reported that they always had these medications available.

DISCUSSION

National standards are a necessary step in the development of palliative care in any country. While a growing number of countries has developed such standards, there is very limited reference in the published literature on their development process. When national standards developed by a working group assembled by Pallium India were used in the evaluation of palliative care services all over India, among the individual items of the “national standards”, clinical care components and drug availability scored high across the board for all provider types and sizes. Although this finding might raise questions about the veracity of the reports, it must be remembered that the questionnaire was sent only to recognized palliative care institutions. In India, since the mid-1990s, palliative care practitioners have, albeit informally, tried to set standards for palliative care. That early work laid the foundation for overcoming barriers to opioid availability. As a result, these recognized palliative care programs have had access to an uninterrupted supply of oral morphine since 1998. However, these excellent scores are in no way representative of the country as a whole. They need to be put in perspective. Approximately four-fifth of all the country's palliative care centers are in Kerala, and many states in the country have no palliative care services at all. It is possible that those who turned in their assessment were the ones who were most confident of submitting presentable reports.

Some weaknesses in the survey and methodology surfaced during the data gathering period. These problems should be addressed and corrected if the standards audit is repeated.

-

Literature suggests that palliative care availability varies by region, and is more prevalent in urban areas than in rural regions.[12] Therefore, respondents should have been asked to indicate their geographical location by state and whether they serve urban or rural communities

-

The McDermott study used the following categories for provider types: NGO, public hospital, private hospital, and hospice. Similar categories could have been used in a standards audit, or providers could have been allowed to describe their type of service in their own words

-

The availability of opioids across settings might seem surprising, so the scale of “Never > Rarely > Sometimes > Often > Always” could be narrowed to a specific period of time. For example, the questions could have been phrased: “Have you experienced an uninterrupted supply of oral morphine/step 3 opioids in the past year?”

-

Many respondents found the PDF format of the survey challenging, especially because once completed, the survey could not be saved in PDF format. A Word document that could be sent as an attachment might be more user-friendly

-

Furthermore, there is a fear that development of national standards may have a negative effect in countries with limited resources–that if Governments insist on standards, some palliative services may not be able to continue operation if unable to meet the standards.

The way forward

The “National Standards Tool” for India, developed over a two-year period is available for free access on the internet.[13] Forty-nine palliative care services used it for self-evaluation of their services. The results show that

-

Most hospices and palliative care providers met the essential measures most of the time

-

“Essential” standards were met more often than “desirable” or “aspirational” standards

-

Most programs reported no interruptions to their supply of pain medications and free availability to poor patients

-

Community-based and hospital-based services reported different levels of services

-

Program size positively influenced service availability.

The users of palliative care standards need to be trained to implement the standards and invited to provide continuous feedback as part of the ongoing review of the standards. The development of national standards is not a one-time event. Standards should evolve and become more rigorous as a way to help advance the field of hospice and palliative care. The use of essential and aspirational standards in this project is one way to stimulate this advancement. Over time, aspirational standards can become essential and new aspirational standards can be identified. Standards, once developed, should be used by national palliative care associations to make service provision more consistent among all providers. National palliative care policies should require that service providers meet the minimum standards of care. The National Quality Forum (NQF) preferred practices in the U.S.A. are an example.[14] Standards also serve as a resource for palliative care training, service development, and the development of standardized data collection tools. Once palliative standards are established, they should ideally be monitored through national palliative care organizations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), the contribution of Ms. Katherine Pettus, Pettus Foundation, USA, in editing the document and of Ms. Jeena Manoj in the final stages of editing and submission.

Source of Support: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- Global atlas of palliative care at the end-of-life. London: Geneva: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance and World Health Organization; 2014. p. :1-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- National associations survey: Advancing hospice and palliative care worldwide. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:386-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- National cancer control programmes: Policies and managerial guidelines. (2nd ed). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. p. :91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of hospice and palliative care in the United States. Omega (Westport) 2007. 2008;56:89-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Task Force Members. The National agenda for quality palliative care: The national consensus project and the national quality forum. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:737-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring hospice care: The national hospice and palliative care organization national hospice data set. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:316-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global view. J Pain Symptom Mgmt. 2008;35:469-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:1094-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring: An illustrative analysis. The methods and findings of quality assessment and monitoring. Vol 3. Ann Arbor Michigan: Health Administration Press; 1985. p. :12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospice and palliative care development in India: A multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:583-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standards Audit Tool for Palliative Care Programs. Available from: http://palliumindia.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/palliumindia-standardstool.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of palliative care at US hospices: Results of a national survey. Med Care. 2011;49:803-9.

- [Google Scholar]