Translate this page into:

How Cancer Supportive and Palliative Care is Developed: Comparing the Policy-Making Process in Three Countries from Three Continents

Address for correspondence: Prof. Soudabeh Vatankhah, Department of Health Services Management, Health Management and Economics Research Center, School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. E-mail: Vatankhah.s@iums.ac.ir

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Supportive and palliative care worldwide is recognized as one of the six main cancer control bases and plays an important role in managing the complications of cancer. Limited studies have been published in the field of this policy analysis in the world.

Aim:

This study aimed to analysis the policy-making process of supportive and palliative cancer care in three countries.

Methodology:

This qualitative study is a part of a comparative study. The data were collected through reviewing scientific and administrative documents, the World Health Organization website and reports, government websites, and other authoritative websites. Searches were done through texts in English and valid databases, in the period between 2000 and 2018. To investigate the policy process, heuristic stages model is implemented consisting of the four stages: agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation.

Results:

The findings of the study were categorized based on the conceptual model used in four areas related to the policy process, including agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation, and evaluation of cancer palliative care policies.

Conclusion:

Several factors are involved in how cancer palliative care policy is included in policy-makers' agenda, understanding a necessity, raising public awareness, and acceptance as a result of sensing the physical and nonphysical care outcomes. The stages of development, implementation, and evaluation of palliative care in countries regardless of existing differences are a function of the health system and context of each country.

Keywords

Cancer

palliative care

policy-making process

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, the epidemiological trend has shifted to chronic and noncommunicable diseases, and the aging population as a result of increased life expectancy, great increase in the incidence of cancer and other chronic diseases, as well as urbanization and changes in lifestyle, all in all, have become challenges, and overcoming their complications and outcomes require taking new and innovative measures.[123] One of the most important challenges, which almost all health systems in the world are facing, is the increase in cancer incidence and burden.[4] Cancer is one of the most important causes of death all around the world, with about 14.1 million new cases and 8.2 million cancer deaths globally in 2018.[5] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the incidence of cancer is expected to raise from 10 million in 2000 to 15 million in 2020, with about two-third of the increase occurring in developing countries[6] in addition to, Iran has faced many structural and procedural problems with the purchase of the best health interventions.[7]

In 2007, the WHO defined supportive and palliative care as a series of measures taken with the aim of improving the quality of life for patients and their families, in order to resolve challenges and problems caused by incurable and life-threatening illnesses, through pain relief or prevention, early diagnosis, complete assessment, and treatment of pain and other (psychological and physiological) problems.[8]

Studies show that while many high-income countries have developed and implemented national policies in order to provide supportive and palliative care,[910] and despite the high burden of this disease, many low-income and middle-income countries have developed no plans and policies for designing and the provision of supportive and palliative care at local and national levels yet.[11] Despite the importance of addressing this issue, few systematic studies have been published globally so far in the field of policy-making and analyzing the policies regarding these care services. Although this type of care has many benefits for patients, their families and also the health system, not enough attention has been paid to this issue. Therefore, it should be figured out how policy-making process works in this area.

Conceptual model

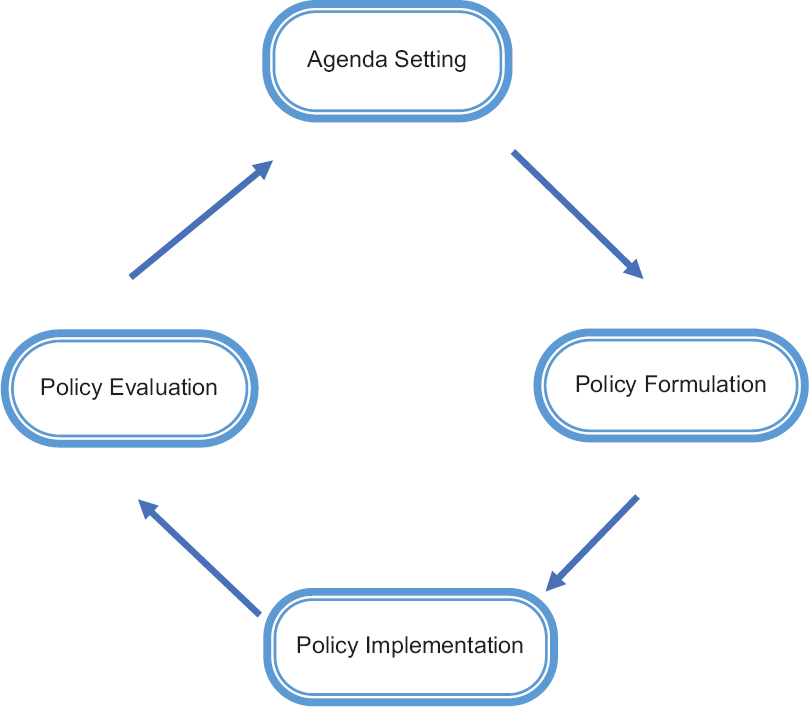

In the science of public policy-making, and subsequently, health policy-making, a variety of frameworks are usually implemented. One of the most famous frameworks used in public policy making is the heuristic stages model. This process refers to the method in which policies are initiated, developed, formulated, selected, implemented, and evaluated. The heuristic stages model is the most common approach to understanding the policy process.[12] With the aim of better understanding policy-making process, this study presents the results related to the process of policy-making in the field of cancer supportive and palliative care, based on heuristic stages model that includes four stages agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. Figure 1 shows the heuristic stages model of the policy-making process.

- Heuristic stages model of the policy making process

METHODOLOGY

This qualitative study is a part of a comparative study, carried out to analyze the policies of cancer supportive and palliative care in various countries around the world. The studied countries were purposefully selected, based on the reports of the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). This report has investigated palliative care status in 80 countries around the world, and classified the countries, using 20 quantitative and qualitative indicators through five categories including palliative and health-care environment, human resources, affordability of care, quality of care, and community engagement (EIU 2015). Accordingly, from each group, one country was selected according to its access to information and the availability of government services, in order to examine the pattern of palliative care services. The selected countries consisted of UK, Malaysia, and South Africa. The data were collected through reviewing scientific and administrative documents, WHO website and reports, government websites, and other authoritative websites. Searches were done through texts in English and the databases Science Direct, Scopus, and PubMed, in the period between 2000 and 2018. To investigate the policy process, heuristic stages model is implemented consisting of the four stages: agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. Key health indicators in the field of the present study are investigated, which are presented in Table 1.

| Source | South Africa | Malaysia | UK | Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WB | 57,398,421 | 32,042,458 | 66,573,50 | Population (2018) |

| WB | 65.29 | 75.37 | 80.6 | Urban population (%) |

| WB | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.59 | Population growth rate |

| WB | 29.178 | 24.621 | 17.619 | Population 0–15 years (%) |

| UNDP | 0.699 (113 Rank) | 0.802 (57 Rank) | 0.922 (14 Rank) | 2018 HDI |

| WB | 295,456.19 | 296,535.93 | 2,650,850.18 | GDP |

| WB | 5480 | 9860 | 42,370 | GNI |

| WB | 470.80 | 385.62 | 4355.86 | Per capita expenditure on health |

| WB | 62.774 | 75.3 | 80.956 | Life expectancy |

| WHO | 41,300 | 21,500 | 166,135 | Cancer mortality (2016) |

| WB | 43.3 | 8.3 | 4.3 | Mortality rate for children under 5 years in 1000 births |

| WB | 138 | 40 | 9 | Maternal mortality in 1000 live births |

| WHO | Africa | Western Pacific | Europe | WHO region |

| WB | Upper-middle income | Upper-middle income | High | Income level classification |

| WHO | 8.20 | 4.00 | 9.88 | Health expenditure (% GDP) 2015 |

WHO: World Health Organization, WB: World Bank, UNDP: United Nations Development Programme, GDP: Gross Domestic Product, GNI: Gross National Income, HDI: Human development index

RESULTS

The findings of this study are based on the model used in four stages of the policy process, including agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. Table 2 gives a brief overview of the categories of these processes in the three selected countries.

| Country | Process components | Significant events |

|---|---|---|

| UK | Agenda setting | After the World War II, for the first time, due to an increase in cancer patients and people with war injuries from caused by the war, the need for the creation a single body was felt in order to provide this type of service |

| Policy formulation | 1967: Saunders’ speech in the USA | |

| 1995: Calman–Hine report | ||

| 1970: Opening of hospice institutions with the support of NHSs | ||

| 1980: Beginning of negotiations between charities and NHS | ||

| 1991: Founding the national council for palliative care, intensive care and hospice, and implementing local groups 2000: Formulation of the NICE clinical guideline for supportive and palliative care, NHS cancer plan, creation of standards for cancer services, development of a strategic draft for evidence-based purchase | ||

| 2003: End-of-life care begins in the UK | ||

| 2004: Changes in the scope of health and palliative care provision for cancer patients; assignment of 50 million Euros to the palliative care sector by NHS. Cooperation begins with the charity sector | ||

| 2008: Developing end-of-life strategies, and establishing the national pediatric palliative care strategy 2016: Codifying government commitments | ||

| Policy implementation | The Ministry of Health manages the public health-care system, but NHS has the executive responsibility, UK’s NHS, as an independent public organization | |

| The UK’s NHS manages the NHS budget and supervises 209 local clinical refounding groups, and ensures that goals obtained by the minister of foreign affairs annually are spent for health-care goals and performance. The public health budget is provided by local authorities | ||

| In 1991, the National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services was founded. Then, the local implementation groups were formed and began to design and plan cancer services in their regions | ||

| Each region worked on its own cancer services plan; moving toward the evidence-based purchase created a framework for developing local policies and recommendations for stronger interactions between agencies | ||

| Protocols were developed for patient referrals including symptom management, pain management, and social and spiritual care for patients under the coverage of the palliative care system through clinical guidelines and specific online protocols | ||

| The Welsh approach of partnership-based health care The UK’s end-of-life care strategy (July, 2008) | ||

| Scottish partnership for palliative care | ||

| Evaluation | The UK’s NHS and the Department of Social Health provide periodic reports on the health impact assessment, patients’ demographic information and the status of service provision | |

| According to these reports, periodic policies such as the end-of-life care strategy are formulated in 2007–2008, and then, measures for end-of-life health care are taken in 2014-2016 | ||

| A report titled National End-of-Life Care Strategy was published in 2008 | ||

| The Care Quality Commission is responsible for organizing health and social care services, and safety and quality standards which consist of hospice services are under this committee. A department has been established to coordinate the places of hospice and palliative care service provision | ||

| Malaysia | Agenda setting | The cultural impact of relevant developments in the UK |

| Policy formulation | The first hospice center was established in 1991 | |

| 2 years later, in 1993, palliative home care services began in the state of Sabah under the supervision of Cancer Society of Sabah | ||

| In 1996, the first palliative medicine center with four beds was established at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital. In the same year, a workshop on palliative medicine was held at the center, visited by the minister | ||

| Conducting the National Palliative Care Conference, and subsequently, approving the palliative care code, which would require all public hospitals to carry out palliative care by the year 2000 | ||

| 2005: Recognition of palliative medicine as a medical specialty | ||

| 2016: Publishing the reports of palliative care need assessment in order to improve services | ||

| Policy implementation | With support and encouragement from the Ministry of Health, palliative care units and teams were formed throughout the country | |

| In July 1998, the Ministry of Health issued official instructions on how to set up palliative care services at public hospitals, and imparted them, as well as two guidelines | ||

| Evaluation | The citizens of this country are asked for their views on services and needs, through public opinion polls | |

| In 2016, the Hospis Malaysia published a report titled Needs Assessment of Palliative Care | ||

| South Africa | Agenda setting | Global health policies, increased mortality rates, cancer incidence, and AIDS |

| Policy formulation | 1979: Saunders’ speech | |

| 1988: The formation of Hospice National Association of South Africa | ||

| 2001–2002: Launching an integrated community-based home care plan | ||

| 2003: Renamed to the Hospice Palliative Care Association of South Africa | ||

| 2006: Membership of 120 organizations in the Association | ||

| 2014: The document WHA67.19 was proposed by the WHO and the South Africa’s membership of this program | ||

| 2016: Approving a political framework for palliative care | ||

| Policy implementation | In 2016, the National Health Council presented a policy and practical framework for palliative care | |

| The committee began its activity with the aim of “revolution in health care through palliative care” | ||

| Evaluation | Palliative care policy-making is very recent in South Africa and has not yet been evaluated | |

| Regarding the quality assessment of services provided by the charity sector during 2005, a set of patient care standards was formulated in collaboration with the COHSASA, in order to measure the quality of services provided by member hospitals | ||

| The standard manual has been edited twice with the cooperation of the COHSASA, and the third version is currently in use (111) |

NHSs: National Health Services, NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, WHO: World Health Organization, COHSASA: Council for Health Services Accreditation of Southern Africa

Agenda setting in cancer supportive and palliative care

During her visit to the United States (1963), in a lecture at Yale University, CicelySaunders proposed to establish a center for nursing and caring for incurable patients. After this speech, the hospice movement expanded in other countries, including the UK. Gradually, governments and health insurance companies figured out the importance of these centers and approved necessary funds for the development of these services.[13]

The concept of palliative care in Malaysia has been a result of influence of the West, in particular, Britain, on this country. At first, palliative care was not easily accepted. Despite this disapproval, several Malaysian health authorities took measures to improve the quality of life in advanced cancer patients. In late 1991, the first Hospice At Home Program began in the Pena Hospice Malaysia ng Cancer Society. At the same time, in Kuala Lumpur, Hospice Malaysia started its activity as a nonprofit charitable organization and provided palliative medicine services.[14]

A speech tour by Saunders in 1979 also facilitated the development of hospice programs in South Africa. Basic hospice care programs in this country were created in accordance with the British model.[15] Home care has significantly become popular in South Africa, due to the increased number of people in need of care and supportive services as a result of the increasing prevalence of HIV, tuberculosis and noncommunicable diseases such as cancer.[16] One of the biggest challenges associated with palliative care in Africa is the increased number of cancer patients, many of whom are in need of palliative care.

Formulating policies on cancer supportive and palliative care

Following public discussions on inequalities in cancer treatment, throughout the UK, a cancer expert group was founded at the Ministry of Health to provide grounds for the development of a cancer service organization in the UK and Wales. In 1995, the group published its report under the name of Calman–Hine report.[17] This report proved the need for specialized palliative care teams and provided a framework for policy-making and the development of cancer services. In 2004, the health scope changed in the UK. The National Council for Hospice and Palliative Care Services, established in 1991, was renamed the National Council for Palliative Care to cover all patients in need of such services.[18]

In March 1993, palliative care was provided throughout the South China Sea in the State of Sabah as a homecare program, by Sabah Cancer Society. The concept of palliative care gradually grew and spread to Penang and Kuala Lumpur. A great advance in this field was the establishment of the first palliative care unit which began its activity in 1995, at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Kota Kinabalu. This center only provided palliative care at first, and its staff was officially trained in this field. In 1996, a workshop on palliative care was held at the hospital, which provided an opportunity to officially introduce palliative care. Finally, the government obliged all public hospitals to establish palliative care units by the year 2000.[14]

In 1988, 14 hospice centers came together, in order to form a national association called the South African Hospice Association. In 2003, the name was changed to the Hospice Palliative Care Association (HPCA). Before 1988, hospitals dealt mostly with oncologic patients, but with the effects of AIDS epidemic, hospice programs changed the methods of care provision and increased access to services. In the years 2001–2002, the South African Association approved an integrated community-based home care program. In the first phase, 28 hospice centers enrolled in the program.[15]

The implementation of policies on cancer supportive and palliative care

Practical programs used to be different across the UK. Initially, palliative care services were volunteer work. By the late 1970s, the government had approved no funds for supporting palliative medicine. Initial efforts were made to establish a strategic development plan in Wales, and Calman–Hine report had a significant impact on palliative medicine being supported by the National Organization for Medicines.[19] In the late 1980s, hospice service developed as palliative care services throughout the country. The charity foundations along with National Cancer Institute and the Ministry of Health made some decisions through discussions, and in 1991, The National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services was established.[20] Then regional executive groups were established and started designing and planning in their regions. In addition, protocols were developed for patient referral.

Formulating the imparted guidelines in Malaysia introduced two methods: first, the establishment of a unit in the form of a palliative care unit with at least six special beds and full-time nurses. In this regard, small hospitals can form palliative care teams with doctors and nurses to provide palliative care throughout the hospital, but without special beds. An evaluation of palliative care services carried out in Malaysia in 2001 noted a total of 11 palliative care units and 49 palliative care teams in public hospitals and 18 PCAs in this country.[21] In 2005, the Ministry of Health officially recognized the discipline as a medical supervisor. At present, nongovernmental organizations such as the Hospice Malaysia and the National Cancer Society of Malaysia are the major providers of palliative care. By the year 2015, 25 nongovernmental training organizations provided this service free of charge.[22]

South African mentorship program

The mentorship strategy of the HPCA is based on the strategic goal of empowering the organizational systems and structures necessary to provide quality palliative care at regional, state, and national level and increasing the capacity of service provision by hospices. As a result of the increased number of AIDS patients, the National Health Council presented a political and practical palliative care framework in 2016. The committee began its activity with the aim of revolution in healthcare through palliative care. The purpose of this framework is to provide specialists' guides in the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of progress in order to achieve the resolution World Health Assembly 67.19 (this resolution, title “Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course” was presented by the World Health Organization, in 2014, following an agreement on Cancer Control and Prevention) objectives. Seven task forces have been created in this regard.[2324]

The assessment of policies on cancer supportive and palliative care

Government commits to high-quality end-of-life care at the Department of Health and Social Care in the UK. This department provides different reports on the implementation of palliative medicine programs, which are reflected in the policies in the field of national medicine. In 2000, the Cancer Quality Improvement Program set standards for cancer services. The National Institute of Medicine and the Department of Health and Social Care provide periodic reports on the evaluation of the health effects and necessary demographic information of patients and the service provision status. In 2008, a report was published titled National End of Life Care Strategy. Following this report in 2014, the Actions for End of Life Care: 2014–2016 was released to update the data until 2016.[2526] Prior to these reports, the guideline Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient was formulated. Along with this document, another guide named Preferred Priorities for Care was published. All of these documents and reports follow the service quality standards developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.[27] The Care Quality Commission has been established to organize health and social care services and quality and safety standards. The services provided by hospices follow these standards, and a department has been established to coordinate hospice and palliative care services.[25]

In 2016, Hospis Malaysia published the report palliative care needs assessment. The center is one of the largest to provide palliative care in Malaysia. This service is mostly provided by charity in this country. During 2015, the center began to assess palliative care needs, using the WHO framework and through a public survey of citizens. These studies give a chance to both the Ministry of Health and private palliative care service providers to correct their policy-making, service, and educational plans, in order to provide the best services in the country.[28]

Policy-making in the field of palliative care has not been evaluated in South Africa yet. However, to assess the quality of services provided by the charity sector in 2005, a set of standards for patient care was developed in cooperation with the Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa (COHSASA) in order to assess the quality of services provided by member hospitals. The standards have been edited twice with the collaboration of COHSASA, and the third version is currently in use. The HPCA implemented a star rating system, in order to accredit the internal process of hospices moving toward full accreditation, in which hospices are ranked after internal accreditation according to their progress. The external accreditation is performed by COHSASA and HPCA. Since November 2015, the accreditation process is done by an electronic self-evaluation tool, and the assessment of the mentorship program has been implemented since 2010.[1623]

DISCUSSION

In the field of policy agenda setting, unlike UK, where on the one hand, the ground for hospice movement was provided by raising public awareness and support from the church, and on the other hand, the interest of statesmen and the insurance companies provided financial resources for these services both by the government and privately, in Malaysia, due to the cultural influence of the West, these services not only had not met public interest, but also were rejected because of publicly being known as luxury services. This issue speaks of the profound and influential effects underlying factors associated with a policy, such as social, cultural, economic, and political factors, may have on the adoption of policies on public health by policy-makers. In addition, Malaysia is a good example of the influence of physical and financial access on the public acceptance of care. In South Africa, too, health care is based on the UK model. However, in addition to cancer, South Africa has been facing the double burden of communicable diseases such as HIV. In fact, as a result of the care needs of these patients becoming a health challenge for the country, policy-makers are obliged to address this type of care inevitably.

In the field of formulating policies, almost simultaneously in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the formulation of policy documents has been considered by policy-makers. However, the issue of debate is who is responsible of such cares in these three countries, which indicates several differences; in the UK, the Ministry of Health, as the major care provider has fulfilled its dominant role in providing care. The UK government is also responsible for setting the main framework for formulation, planning, and implementation of these care services, as one of its main tasks, and has also ensured the proper geographical distribution of hospices, and official recognition of palliative medicine, and has determined the areas under coverage, in accordance with the situation. However in Malaysia, unlike the UK, the government sector has taken charge of these services with a delay, under the influence of activities of other sectors involved in the health sector, by holding a national conference and formulating official guidelines for public hospitals. In South Africa, the major policy-maker and formulator is the HPCA of South Africa, formed by a joint of 14 hospice centers. After the needs of hospitals being identified, the integrated community-based home care program has been approved as the executive arm of this association and in collaboration with other organizations and has become a basis for such policies.

In the field of policy implementation, in the UK, despite the strong role of public sector and centralized decision-making and policy-making, there is a widespread, and in some cases, higher participation of other sectors, including voluntary sectors, in providing and funding services. There is a tendency toward the assignment of service provision to charity and private sectors, in order to increase the service coverage in cooperation with the National Health Service, decentralize programs and policies, and provide equal access to care, through regional implementation and planning. In Malaysia, nongovernmental organizations are the main providers of care. The government sector provides limited services in small hospitals by 11 palliative care units and 49 care teams in accordance with the imparted guidelines, while the number of nongovernmental providers is increasing. Since South Africa has been struggling with the challenges of proper health-care management and new structuring of care provision, especially since the end of apartheid in 1994 and has faced various ups and downs, first of all, efforts have been done to increase the capacity and the strength of organizational systems and care provision structures, through a mentorship program, while focusing on hospices. Then, it is tried to integrate mentorship services through community-based home care, and finally, the National Health Council of the country has determined the main framework for these care services, in order to make revolutionary changes in health care, through palliative care. It seems that due to the high number of HIV patients in South Africa, the government is taking authority over palliative care and has taken measures to provide palliative care. To implement the relevant policies, the government has formed seven task forces with the responsibilities regarding the policy-making, funding, support, training, availability of medicines, vulnerable populations, and ethical issues and has sought to highlight its own role in supporting the present providers, as one of its policies in this area.

In the field of policy evaluation, in UK, there is strong and consistent government supervision in order to improve the quality of services. The necessary standards are set by the cancer quality improvement taskforce and are periodically evaluated and reported by the National Health Service and the Department of Health and Social Care. The considerable point is that these standards focus on the end-of-life care, which can also be attributed to the high elderly population in this country. In Malaysia, evaluation is affected by implementation, and nongovernmental sectors, especially the charity sector, are the pioneers in the evaluation of these care programs as well as funding and implementing them. They assess care services, based on the WHO framework and according to surveys. In fact, a charity institution plays the leading role in policy-making, education, and palliative services both for the public and private sectors, and everything depends on charity. Although in South Africa, due to the newness of these care services, policy evaluation has not reached the implementation phase yet, the service quality evaluation and the mentorship program are currently being carried out. In hospices, this occurs as a combination of internal accreditation by centers and external accreditation under the supervision of public sector, The COHSASA, which indicates the enforcement and the empowerment of government supervision.

CONCLUSION

Several factors are involved in how cancer palliative care policy is included in policy-makers' agenda. First, understanding a necessity as a result of an increase in the number of chronic patients in need of care; second, raising public awareness and acceptance as a result of sensing the physical and nonphysical care outcomes, such as physical and financial access; and third, attracting the attention of policy-makers and other providers of financial and nonfinancial resources, including the private and charity sectors.

In the formulation of policies, the main issue is the government's protective role, which in the UK includes all supportive duties, while in Malaysia and South Africa, the government only fulfills some of these tasks, with the nongovernmental sector sometimes taking over them.

In the field of policy implementation, it seems that there are three different methods of providing supportive and palliative care: government and nongovernment provision of care through collaborative policy-making and planning in the United Kingdom, potent nongovernment and limited government care provision with a feeble government policy-making in Malaysia, and nongovernment care provision through centralized and imperative government policy-making and planning in South Africa.

Finally, three types of evaluations are involved, proportional to the systems of care provision: a government and internal evaluation in the UK, a nongovernmental internal evaluation in Malaysia, and a combination of internal and external evaluations in South Africa.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was part of a PhD thesis supported by School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant no: IUMS/SHMIS_1395/9221557202.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of a PhD thesis supported by the School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant no: IUMS/SHMIS_1395/9221557202).

REFERENCES

- Iran's health system and readiness to meet the aging challenges. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:1716-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of health system challenges and opportunities for possible integration of diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis services in South-Eastern Amhara Region, Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Paying for chronic disease care. In: Nolte E, McKee M, eds. Caring for People with Chronic Conditions: A Health System Perspective (1st ed). Berkshire: Open University Press; 2008. p. :195-221.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological state, quality of life, and coping style in patients with digestive cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:125-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative analysis of national documents on health care services and pharmaceuticals' purchasing challenges: Evidence from Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:410.

- [Google Scholar]

- c2019. Geneva: Cancer Control: Knowledge into Action. WHO Guide for Effective Programmes, Inc; Available from: https://www.who.int/cancer/modules/en

- Country Reports. In: Centeno C, Garralda E, eds. EAPC Atlas of Palliative Care in Europe (Full ed). Juan José Pons: European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC); 2013. p. :334-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2012. Resource and Capability Framework for Integrated Adult Palliative Care Services in New Zealand. Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz

- Perspective of patients, patients' families, and healthcare providers towards designing and delivering hospice care services in a middle income country. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:341-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Areview of specialist palliative care provision and access across London – Mapping the capital. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2017;9:33-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electronic palliative care coordination systems: Devising and testing a methodology for evaluating documentation. Palliat Med. 2017;31:475-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- c2000. Heritage Foundation 2018 Index of Economic Freedom. Inc. Available from: https://www.heritage.org/index/country/southafrica

- Provision of services. In: Healy J, ed. Malaysia Health System Review (1st ed). Malaysia: Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2013. p. :63-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Government health insurance for people below poverty line in India: Quasi-experimental evaluation of insurance and health outcomes. BMJ. 2014;349:g5114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding how low-income families prioritize elements of health care access for their children via the optimal care model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:585.

- [Google Scholar]

- c2008. London: End of Life Care Team Department of Health, Inc. Available from: https://www.orderline.dh.gov.uk

- c1992. Shanthi Ellen Solomon. California: Loma Linda University; Available from: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/270

- 2016. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Kuala Lampur: Health Technology Assessment Section; Available from: http://www.inahta.org/members/mahtas

- 2012. Sithole. Kwazulu-Natal: Durban University of Technology; Available from: https://openscholar.dut.ac.za/bitstream/10321/810/1/Sithole_2012.pdf

- Access to palliative care. In: Curie M, ed. Equity in the Provision of Palliative Care in the UK: Review of Evidence (1st ed). London: Personal Social Services Research Unit; 2015. p. :31-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- cancer palliative care system in Iran: The past, the peresent and the future. 2019. Support Palliat Care Cancer. 1:7. Available from: http://journalssbmuacir/spc/article/view/11929/13735

- [Google Scholar]

- c2000-01. London: Ministry of Health Department of Health and Social Care, Inc. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-commits-to-high-quality-end-of-life-care

- Kuala Lampur: Medical Development Division Ministry of Health Malaysia. 2010. Palliative Care Services Operational Policy. National Library of Malaysia; Available from: http://www.moh.gov.my/images/gallery/Polisi/PALLIATIVE_CARE.pdf

- [Google Scholar]