Translate this page into:

A Survey of Medical Professionals in an Apex Tertiary Care Hospital to Assess Awareness, Interest, Practices, and Knowledge in Palliative Care: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sushma Bhatnagar, Room No. 242, Dr. BRA Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, AIIMS, New Delhi - 110 029, India. E-mail: sushmabhatnagar1@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Medical discipline in India focuses on cure rather than comfort care. Palliative care is concerned with improving quality of life and relieving sufferings in patients with advanced incurable terminal diseases. Palliative care in India is still in infancy stage due to lack of knowledge, attitude and skills among health care providers. The reason being lack of training in under graduate as well as postgraduate teaching curriculum and lack of sensitization among policy makers.

Aims and Objectives:

To assess the awareness, interest, practices and knowledge in palliative care among medical professionals working in a tertiary care hospital.

Materials and Methods:

All participants were mailed proforma to be filled in a fixed format including details of their qualification, demographic data, their field of work, their training in palliative care and multiple choice questions regarding awareness interest, practices and knowledge of palliative care.

Results:

Out of 186 respondents, 56% had not received any basic training in palliative care. 81% wanted palliative care education to be included in undergraduate curriculum. Poor program was identified as the most common barrier in learning palliative care. 77% respondents had no idea about home based palliative care services. 50.8% patients dies in hospital in their terminal stage. 88% were interested in learning safe opioid practices. Although 89.8% were aware of the need of palliative care in metastatic cancer but less than 50% were aware of the fact that palliative care is also required in MDR-TB and mental illness.

Conclusion:

This study reflects data of an apex cancer institute of the country. The result of awareness is not very encouraging despite a dedicated palliative care department. So, we can assume what will be the palliative care status in other parts of India where there is no palliative care at all.

Recommendation:

We strongly recommends that palliative care teaching should be incorporated in undergraduate curriculum to sensitize the students from the beginning. Budding residents in their learning phase can play an important role by learning and providing palliative care as the first person to come into contact with the patients are residents. There is a strong need of spreading palliative care awareness all over the country.

Keywords

Awareness

interest

knowledge

palliative care

practices

INTRODUCTION

In Latin, the word “palliative” means “caring.”[1] Palliative care is concerned with improving quality of life in patients with advanced incurable terminal diseases. It can be provided anywhere – home, hospice, nongovernmental organizations, or hospital depending on the patient wishes and resources available. However, in developing countries like India, it is still not a very popular specialty, may be because of poor training or program and poor perks.

Palliative care is growing as a separate specialty in itself which aims at relieving sufferings of both patients and their family members by following a holistic approach. It not only deals with the terminal illness like cancer but also provides comfort care in neurological disorders, mental illness, elderly population, cardiac patients, end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection, Alzheimer's disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and those on dialysis.[2] In India, cancer has taken the lead over chronic cardiac diseases and has become number one killer in the country. India has limited cancer hospitals, and 70%–80% of patients present to the hospital in advanced stages and will require palliative care. In this era of advancement in medical specialties and increase in life expectancy, there is an increased burden of both cancer and chronic progressive noncommunicable diseases. Therefore, the concept of end-of-life care has to be strengthened among medical professionals. India has 908 palliative care services, but <1% population has access to it.[3]

Death is always considered as a result of inadequate medical treatment. Palliative care skills include defining death with dignity and being comfortable with dying patients. Being in a medical profession, we have to deal with death and end-of-life care at some points of life, and we should be mentally prepared to deal with it and should have necessary skills for the same.

Looking at the present scenario, palliative care in India is still in an infancy stage, and there are many challenges and barriers in providing palliative care to our patients. The major challenge is lack of knowledge among physicians as well as patients and lack of sensitization among policymakers. The knowledge of palliative care has been succumbed in journals and publications, and only the tip of iceberg represents its actual skills and application among health-care professionals.[4] WHO has recommended palliative care to be made compulsory in basic medical professional courses.[5] However, in India, palliative care is taught neither at undergraduate and nor at postgraduate level. Hence, this is high time to incorporate principles of palliative care in continuum of medical care in all chronic debilitating diseases. Health-care professionals should have adequate knowledge of palliative care so that this knowledge could be applied practically.

Recently, the Government of India has also recognized the importance of palliative care, and it has been incorporated in the National Health Policy in 2017 by Mr. Narendra Modi. To analyze the status of current knowledge of palliative care, we have decided to conduct a survey among medical professionals working in an apex tertiary care hospital, AIIMS. Improving knowledge of palliative care will improve the quality of palliative care in the country.

With this background, we carried out the present descriptive cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey about the awareness, interest, practices, and knowledge in palliative care among medical professionals working in a tertiary care center. The goal of this study was to have an insight of the gap in palliative care knowledge and measures to improve it.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Design of the study

This descriptive cross-sectional study was undertaken in the Department of Onco-Anaesthesia and Palliative Medicine at DR. BRA, IRCH, AIIMS, New Delhi. AIIMS is 1700-bedded India's apex tertiary care institute located in its capital city Delhi. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics and Research Committee of AIIMS Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Selection of participants

All medical professionals including undergraduates, junior residents, senior residents, and consultants in any age group of either sex in the month of June 2017 were recruited in the study. In AIIMS, we have around 500 undergraduates, 1300 postgraduate residents, 650 senior residents, and 450 consultants.

Aims and objectives

The primary outcome of this study was to assess the awareness, interest, practices, and knowledge in palliative care among medical professionals at AIIMS, New Delhi.

Methodology

All participants were given pro forma to be filled in a fixed format including details of their qualification, demographic data, their field of work, their training in palliative care, and 21 multiple choice questions covering all aspects of palliative care. Awareness, interest, practices, and knowledge regarding palliative care were assessed each by five multiple choice questions. The questionnaire covered the following aspects of palliative care:

-

Biodata, qualification, and training in palliative care

-

Basic concepts of palliative care

-

Safe use of opioids and managing its side effects

-

End-of-life care

-

Spiritual needs of the patients

-

Breaking bad news

-

Quality of life

-

Communication

-

Hospice.

These pro forma containing self-administered, structured questionnaire in English with a brief on the aim of the study were sent via e-mail. The questionnaire was transformed into an online version, and a link to the online questionnaire was e-mailed to all the residents and consultants working in AIIMS. The participation of medical professionals in this study was on voluntary basis. By clicking the link, it was assumed that the respondents have consented to participate in the survey. The survey did not contain any question that could disclose the respondent's identity. A maximum of three e-mails were sent to nonresponders as reminders. The results were kept confidential.

Validity and reliability of the study

The questionnaire was revised and validated by a panel of five medical professionals from different health fields. There were 100% agreements among the five panellists regarding the questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered into the Microsoft Excel chart, and results were interpreted accordingly. Percentages were used in conclusion of data.

RESULTS

E-mail was sent to 2800 list of students, residents, and faculties. Only 186 (6.64%) had responded. Most of the respondents were senior residents (49.4%) and were anesthetists (29.5%) [Tables 1 and 2]. Most of the participants were in the age group of 25–35 years (82.8%). Male-to-female ratio was 70:30.

| Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Faculty | 7.2 |

| Senior residents | 49.4 |

| Junior residents | 27.7 |

| Undergraduates | 15.7 |

| Respondents (specialties) | n |

|---|---|

| Anesthesia | 55 |

| Undergraduates | 18 |

| Surgical oncology | 16 |

| Medical oncology | 11 |

| Medicine | 11 |

| Palliative medicine | 9 |

| Radiation oncology | 9 |

| Surgery | 9 |

| Pediatrics | 8 |

| Neurology | 5 |

| Community medicine | 5 |

| Cardiology | 5 |

| Radiology | 4 |

| Biophysics | 3 |

| Orthodontics | 3 |

| Nuclear medicine | 2 |

| Pathology | 2 |

| Orthopedics | 2 |

| Neuroanesthesia | 2 |

| Critical care | 2 |

| Cardiac anesthesia | 1 |

| Infectious disease | 1 |

| Rheumatology | 1 |

| Anatomy | 1 |

| Ophthalmology | 1 |

Awareness

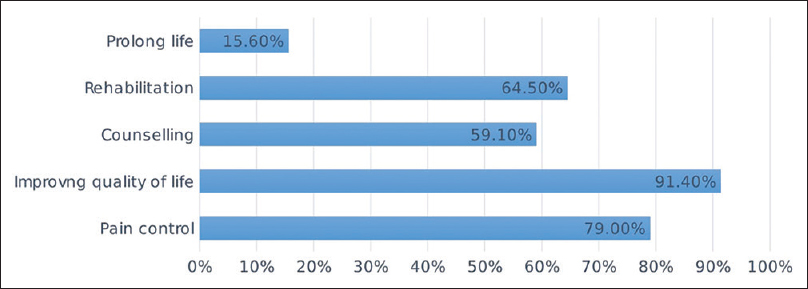

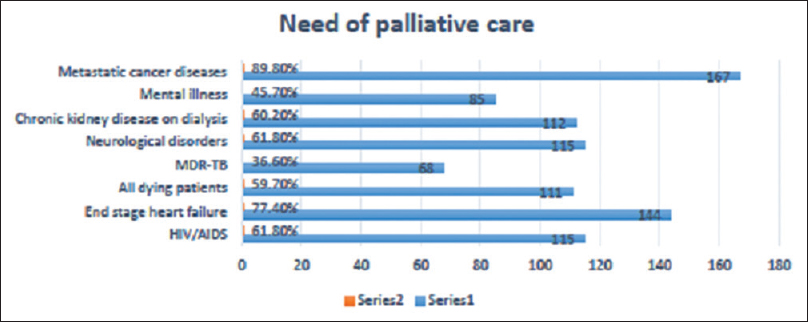

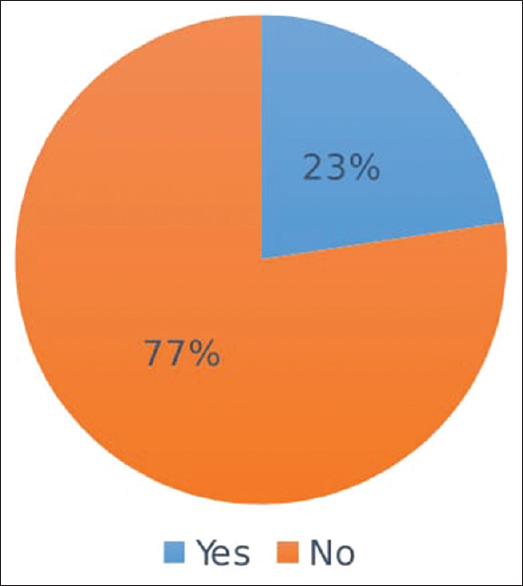

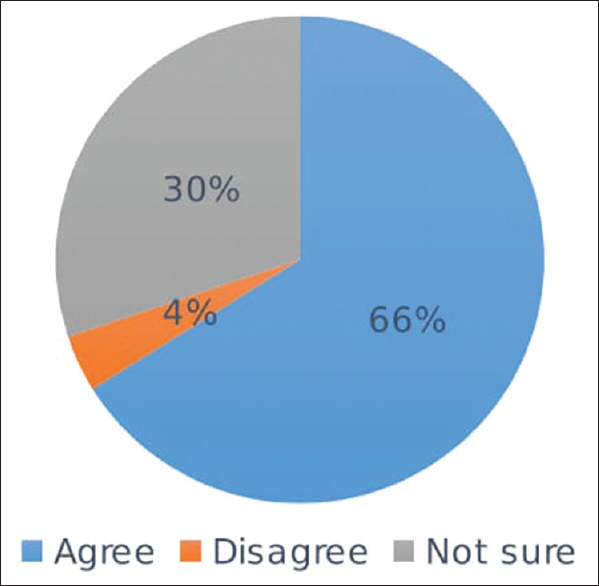

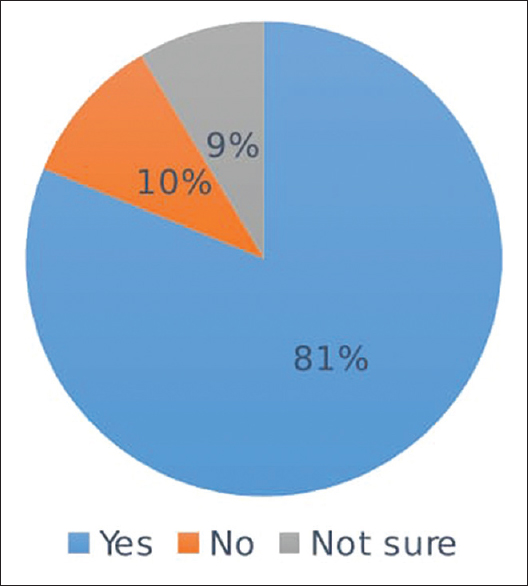

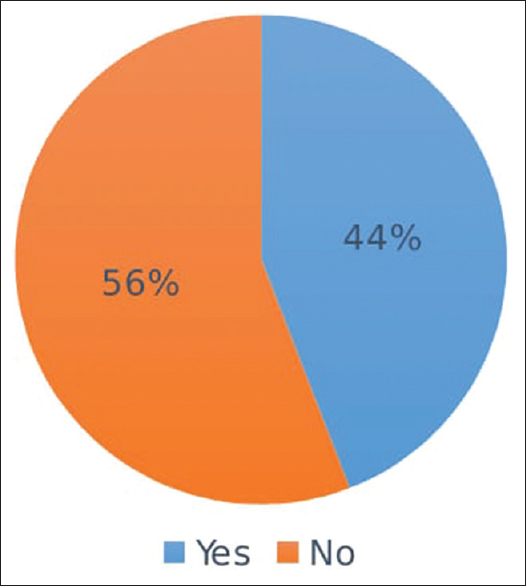

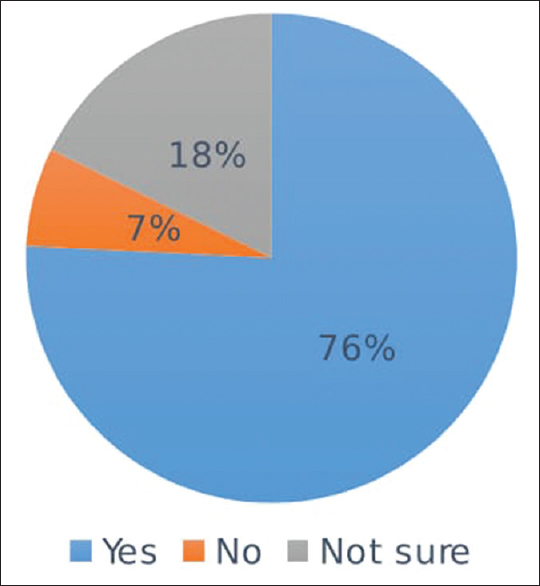

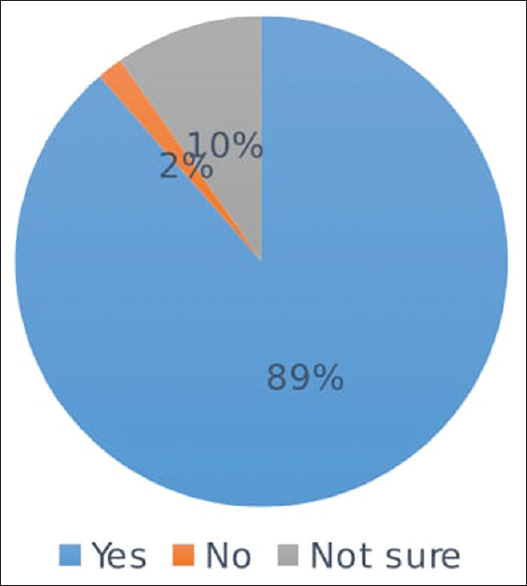

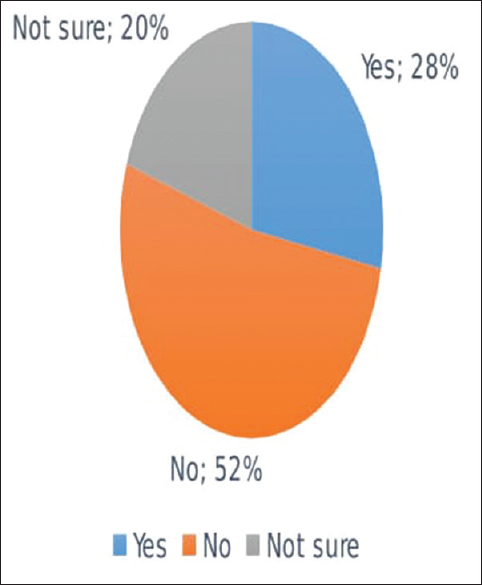

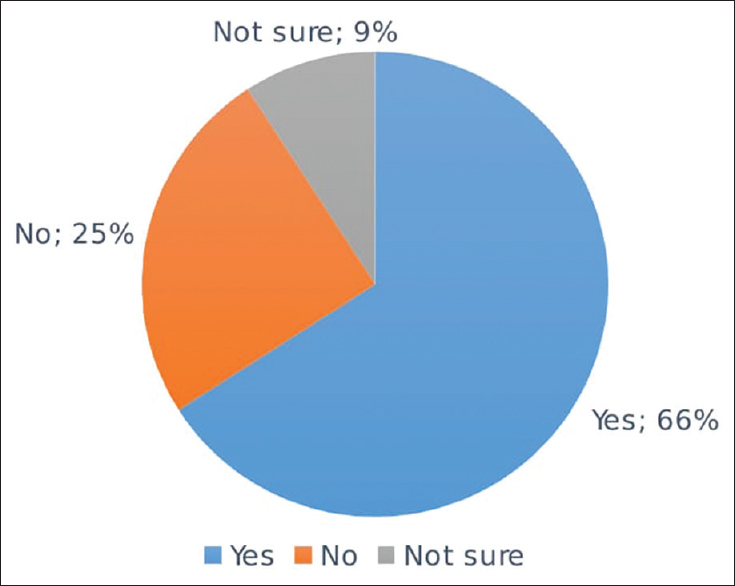

Awareness of palliative care was highly lacking among the participants. About 56% of them had not received any basic training in palliative care [Figure 1]. Most of them were aware of the aim of palliative care, but 15.6% of them had misconception that it also prolongs life [Figure 2]. Although 89.8% were aware of the need of palliative care in metastatic cancer, <50% were aware of the fact that palliative care is also required in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and mental illness [Figure 3]. Seventy-seven percentage of respondents had no idea about home-based palliative care services [Figure 4]. However, 66% had the concept of hospice services [Figure 5].

- Basic training in palliative care (n = 186)

- Aim of palliative care

- Need of palliative care in chronic debilitating condition

- Knowledge on home-based palliative care services

- Hospice knowledge

Interest

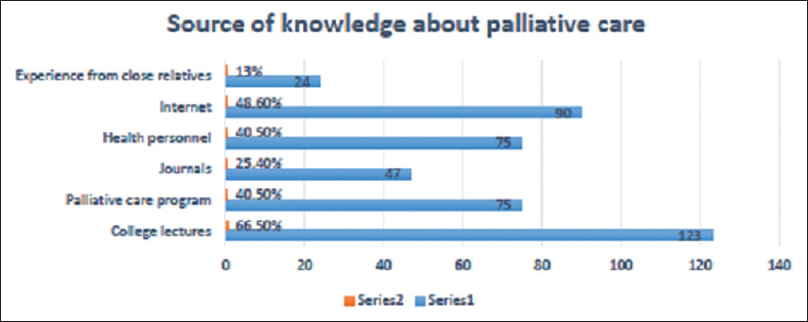

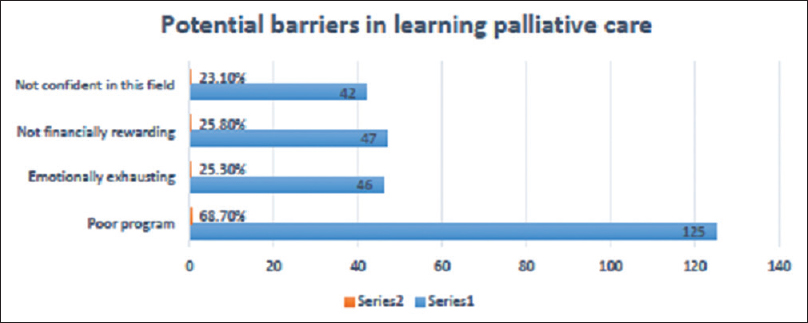

Interest of the participants in learning palliative care was satisfactory. Out of the 186 respondents, 81% wanted palliative care education to be included in undergraduate curriculum [Figure 6]. Fifty-six percent of the respondents had received teaching in communication skills [Figure 7]. Most common sources of knowledge about palliative care were Internet and college lectures [Figure 8]. More than 75% were interested in training in palliative care and learning safe opioid practices [Figures 9 and 10]. Poor program followed by less income was identified as the most common barrier in learning palliative care [Figure 11].

- Palliative care as part of the undergraduate medical curriculum

- Communication skills' teaching in academic curriculum

- Source of knowledge about palliative care

- Interest of training in palliative care

- Interest in learning safe opioid practices

- Potential barriers in learning palliative care

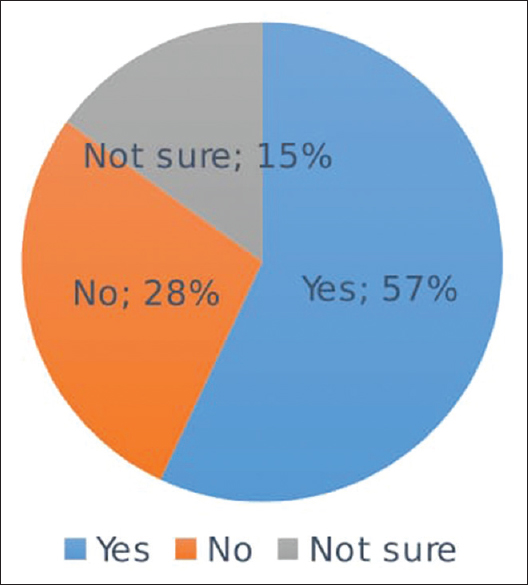

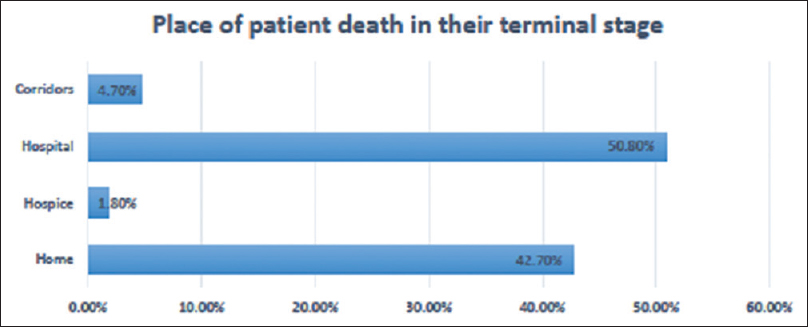

Practices

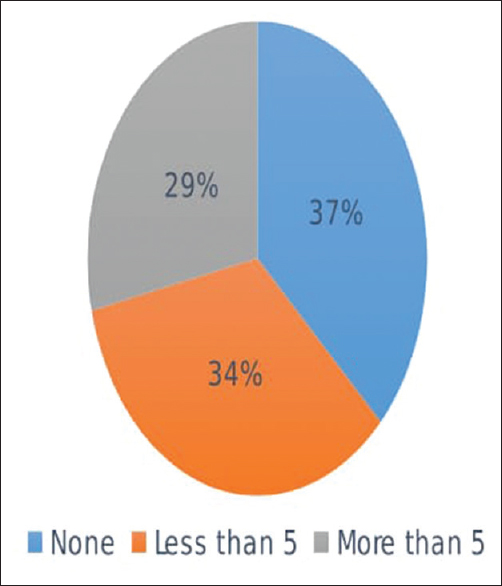

Fifty-seven percent were comfortable in prescribing opioids for acute and chronic pain [Figure 12]. More than 50% were not in favor of resuscitating a gasping patient with an advanced incurable terminal illness [Figure 13]. More than 60% were comfortable in prognosticating patient [Figure 14]. However, 37% of the participants had not counseled for do not resuscitate (DNR) in the past 1 year for terminal illness [Figure 15]. To our disappointment, >50% of patients die in hospital in their terminal stage [Figure 16].

- Comfortable in prescribing opioids for acute and chronic pain

- Opinion regarding resuscitation of gasping patient with an advanced, incurable terminal illness

- Comfort in explaining the patient about his/her poor prognosis or impending death

- Number of patients or relatives counseled for do not resuscitate in the past 1 year for terminal illness

- Place of patient death in their terminal stage in clinical practice

Knowledge

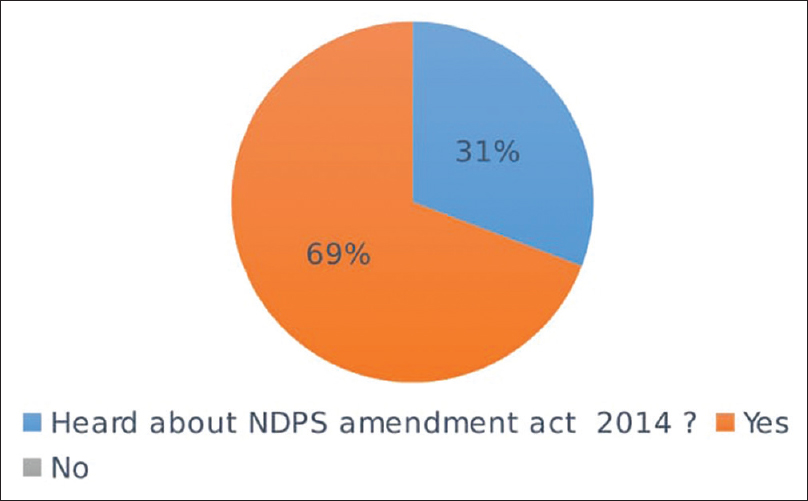

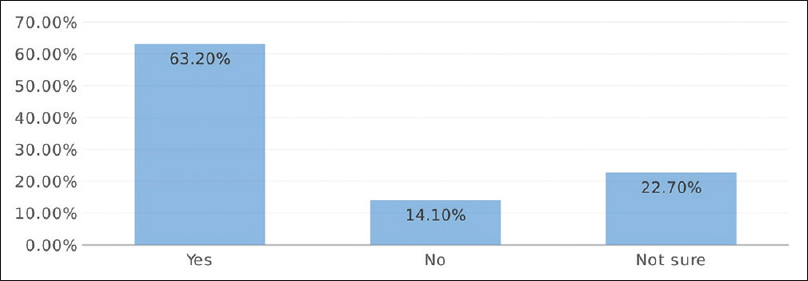

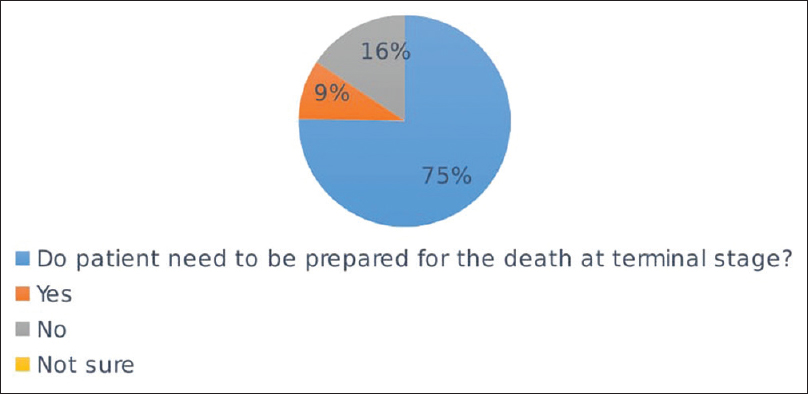

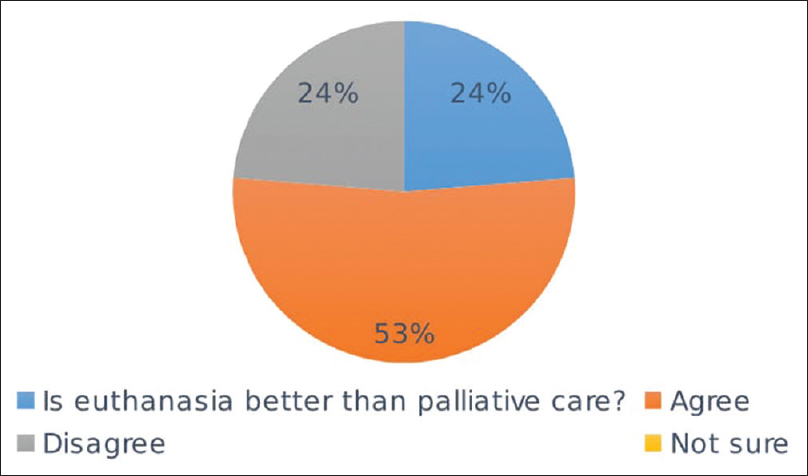

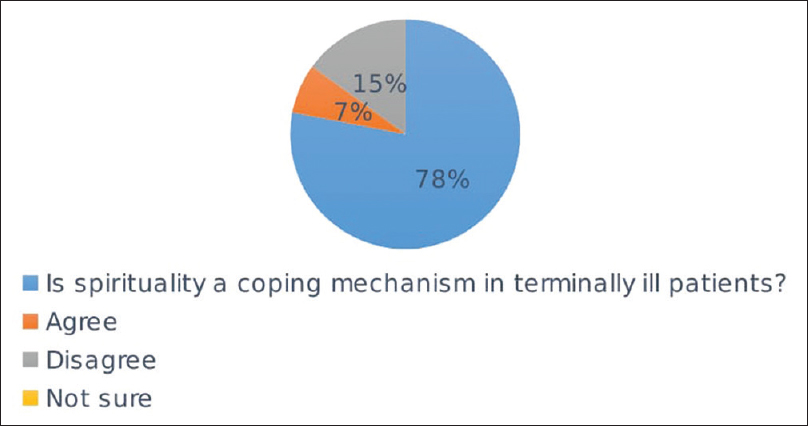

Knowledge of palliative care regarding opioid use, spirituality, euthanasia, and preparation for death was satisfactory among the participants. However, 69% had no idea about the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Amendment Act [Figures 17-21].

- Knowledge of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Amendment Act 2014

- Oral morphine as mainstay approach for the management of moderate-to-severe cancer pain

- Need of patient to be prepared for the death at terminal stage

- Euthanasia better than palliative care at end-of-life care

- Is spirituality a coping mechanism in terminally ill patients

DISCUSSION

This descriptive cross-sectional study was undertaken in the Department of Onco-Anaesthesia and Palliative Medicine at DR. BRA, IRCH, AIIMS, New Delhi, in the month of June 2017.

Response rate of the online survey was 6.64%. Most of the respondents were senior residents (49.4%) belonging to the age group of 25–35 years (82.8%). Male-to-female ratio was 70:30.

Awareness

Awareness of palliative care was highly lacking among the participants. Fifty-six percent of them had not received any basic training in palliative care. Training in palliative care is directly proportional to the knowledge among the trainee.[6] In 2001, Mohanti et al. surveyed palliative care education and training among 49 residents working in a tertiary care hospital and found that the training during residency was considered incomplete by 39% oncology and 62% nononcology residents.[7] In 2012, Alamri investigated knowledge of palliative care among 80 postgraduate residents at King Abdulaziz University Hospital using cross-sectional descriptive study. Only 29.9% of questionnaire were answered correctly, and >70% had not received any prior palliative care teaching. Hence, they recommended to add palliative care in training of medical students.[8]

In our study, participants agreed that the aim of palliative care is improving quality of life followed by pain control, rehabilitation, and counseling similar to another study.[9] Most of them were aware of the aim of palliative care, but 15.6% of them had misconception that it also prolongs life. In another study, 77.7% of participants had myth that palliative care prolongs life.[10] In a study by Shaikh et al., 94.4% of responders were aware of the meaning of palliative care.[11] In our study, 79% of the participants agreed that pain control is one of the aspects of palliative care. Bhadra et al. and Fadare et al. founded similar findings in 70.5%–74% doctors.[910]

Although 89.8% were aware of the need of palliative care in metastatic cancer, <50% were aware of the fact that palliative care is also required in MDR-TB and mental illness. Similarly, 85.2%–93% of doctors agreed that palliative care is most commonly needed in cancer patients.[910] In our study, 60.2%–77.4% of participants were aware of the palliative care need in chronic kidney disease on dialysis and end-stage heart failure similar to findings by other authors.[101213]

Seventy-seven percent of the respondents in our study had no idea about home-based palliative care services. In a study, 53% of doctors agreed that home is the best place to provide terminal care.[9] In India where there is always shortage of hospital beds and other resources, home-based palliative services are boon in relieving hospital and caregiver burden.[14]

Sixty-six percent of the participants had the concept of hospice services since Shanti Avedna Sadan hospice is located very near to our hospital. Similarly, 77% of doctors had heard the term hospice in a study by Bhadra et al.[9] In contrast, in a study by Shaikh et al., 69.7% of nononcologist physicians were unaware of the term hospice.[11]

In 2013, Bhadra et al. evaluated the level of awareness of palliative care among 648 doctors in teaching medical colleges of Kolkata. They concluded lack of training and awareness in comfort care and willingness to learn in this field.[9] Similarly, 75.5% of doctors were unaware of the basic concept of palliative care.[15] However, 74% of health-care providers were aware regarding palliative care in a study.[16]

Interest

Interest of the participants in learning palliative care was satisfactory. Out of the 186 respondents, 81% wanted palliative care education to be included in undergraduate curriculum. Fifty-six percent had received teaching in communication skills.

More than 75% were interested in training in palliative care and learning safe opioid practices. Similarly, in a study by Basol et al., 69% of emergency physicians in Turkey wanted special training to acquire palliative care skills.[17]

Most common sources of knowledge about palliative care were Internet and college lectures. Similarly, the source of palliative care knowledge among 49 medical interns in tertiary institute in Nigeria was through lectures in 49% of the respondents in study by Nnadi and Singh.[18] Internet was source of palliative awareness in 35% of the respondents in a study by Gopal and Archana.[16] In another study, 6% of the residents used to read palliative care journals regularly.[7]

Poor program followed by less income was identified as the most common barrier in learning palliative care. In a study by Shaikh et al., 25.3% of responders considered oncology to be less financially rewarding as compared to other specialties.[11]

Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) is an organization under which all the palliative care activities and program in India are being run. IAPC is concerned with the palliative care awareness, educational programs, drug procurement policies, and drug availability in different parts of the country. The certificate course in essentials of palliative care under IAPC had been started in 2007 as an initiative to enhance knowledge and create interest in palliative care among the participants.

Practices

Fifty-seven percent were comfortable in prescribing opioids for acute and chronic pain. In 2014, Giri and Phalke conducted a cross-sectional study and assessed knowledge about palliative care in 112 medical and 66 dental postgraduate students in Maharashtra, India. They reported that only 34.2% of students had knowledge in terms of correct dose of oral morphine in palliative care.[13] In 2008, Shaikh et al. conducted a cross-sectional study among 236 nononcologist physicians in three tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan and concluded that 14.1% did not know about availability of morphine in the country.[11] Similarly, knowledge of residents regarding opioid use was very low in a study by Alamri.[8]

More than 50% were not in favor of resuscitating a gasping patient with an advanced incurable terminal illness. In another study, 83% of doctors were in favor of resuscitating gasping patient with advanced illness.[15] More than 60% were comfortable in prognosticating patient. Similarly, 73% of doctors were well versed with explaining the prognosis to the patient.[9] However, breaking bad news was not taught to 49% of consultants during their training period.[9] Prognosticating a patient will lead to better acceptance and compliance to treatment and an improved quality of life.[19] However, 37% of participants had not counseled for DNR in the past 1 year for terminal illness. In 2010, Sadhu et al. conducted a study among 326 undergraduate medical (3rd and 4th year), nursing, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy students of Manipal University, India, using 39-point questionnaire. They concluded uncertainty among them in delivering end-of-life care. They found deficiency in knowledge regarding resuscitation in palliative care in 61.7% of students.[12]

Seventy-seven percent of the respondents in our study had no idea about home-based palliative care services. This correlated with our findings that >50% of patients die in hospital in their terminal stage and only 42.7% die at home. Fifty-three percent of doctors preferred home as place for good death.[9] Various studies have reported home as place of death in 16%–86% of patients and hospital as dying place in 14%–76% of cancer patients.[2021] Good palliative care supports death at home with their near and dear ones. Home visits are lacking in India due to training and skills.[22]

Knowledge

Knowledge of palliative care regarding opioid use, spirituality, euthanasia, and preparation for death was satisfactory among the participants. However, 69% had no idea about the NDPS Amendment Act.

About 63.2% of the participants agreed that oral morphine is the mainstay treatment for moderate-to-severe cancer pain. This finding is similar to the study by Shaikh et al. in which 86.3% of responders agreed that morphine is valuable for cancer pain management.[11] Various studies have shown deficiencies in knowledge among residents, especially regarding opioid and its side effects.[23242526]

Nnadi and Singh concluded that palliative care knowledge was poor in 22.5% of the respondents due to ignorance. Fifty percent of the medical interns were unaware of the WHO three-step analgesic ladder for cancer pain management.[18] In 2014, Butola surveyed knowledge, attitude, and practices in palliative care among 210 doctors employed in Border Security Force. He concluded that 75.5% of doctors were not knowing about the basic concept of palliative care and 57% had not heard of WHO analgesic ladder for pain management.[15]

In our study, 78% of the responders believed that the spirituality is a coping mechanism in terminally ill patients. Religious coping mechanism is actually a source of inspiration and spirit.[27]

In 2014, Fadare et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in 170 health-care workers in tertiary hospital of Nigeria and concluded gaps in knowledge regarding palliative care among them.[10]

In 2016, Gu and Cheng evaluated knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward palliative care among 138 Chinese oncologists. Only 29.2% recommended early palliative care, and they had inadequate knowledge about advanced directives and end-of-life care.[28]

In 2011, Weber et al. evaluated knowledge and attitude toward palliative care of 101 medical students (final year) in Germany using a questionnaire-based study. Only 5%–10% of students were confident in dealing palliative care issues and only 33% had scored more than 50% marks.[29]

In 2012, Bogam et al. reported inadequacy in knowledge of palliative care in 109 undergraduate final-year medical students of Maharashtra. Overall poor knowledge was observed among them with average score of 8.11 out of total 17 marks. However, they had good knowledge regarding comprehensive approach, communication skills, euthanasia, and WHO analgesic ladder.[30] Knowledge regarding euthanasia was answered correctly by 59.5% of residents in another study.[13]

Limitation

Most of the participants were senior residents and anesthetists; so, knowledge gap was not assessed among undergraduates and residents of other branches. The study also did not reflect knowledge of medical professionals from all the disciplines as mostly anesthestists had participated in this survey. Moreover, undergraduates, residents, and faculties all were clubbed together in this study. The number of participants was also less in our study. Sample size is too small to extrapolate these findings to all the residents of AIIMS, New Delhi. Our findings from a tertiary care center located in capital city may not be generalized to other centers of India.

CONCLUSION

This is high time to incorporate core themes of palliative care both theoretically and practically in continuum of medical care in all chronic debilitating diseases. Undergraduate training is incomplete unless it is in continuum with regular postgraduate training. This study reflects data of an apex cancer institute of the country. The result of awareness is not very encouraging despite a dedicated palliative care department since 1991. Hence, we can assume what will be the palliative care status in other parts of India where there is no palliative care at all. Awareness programs should be started to identify those in need of palliative care and refer them to palliative specialist.

Recommendation

We strongly recommend that palliative care skills and teaching should be incorporated in undergraduate curriculum to sensitize the students from the beginning.[31] Budding residents in their learning phase can play an important role by learning and providing palliative care as the first person to come into contact with the patients are residents. There is a strong need for spreading palliative care awareness all over the country.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We want to thank all the participants of this survey for giving their time and filling the online form.

REFERENCES

- Hospital-based palliative care: A case for integrating care with cure. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:S74-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The evolution of palliative care programmes in North Kerala. Indian J Palliat Care. 2005;11:15-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Priorities in education and research in palliative care. Palliat Med. 1993;7:65-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Introduction of palliative care into undergraduate medical and nursing education in India; a critical evaluation. Indian J Palliat Care. 2004;10:55-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and experience of palliative medicine among general practitioners in Germany. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007;132:2620-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care education and training during residency: A survey among residents at a tertiary care hospital. Natl Med J India. 2001;14:102-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of the residents at King Abdul-Aziz university hospital (KAAUH) about palliative care. J Family Community Med. 2012;19:194-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Awareness of palliative care among doctors of various departments in all the four teaching medical colleges in a metropolitan city in Eastern India: A survey. J Med Soc. 2013;27:114-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare workers knowledge and attitude toward palliative care in an emerging tertiary centre in South-West Nigeria. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude and practices of non-oncologist physicians regarding cancer and palliative care: A multi-center study from Pakistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:581-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care awareness among Indian undergraduate health care students: A needs-assessment study to determine incorporation of palliative care education in undergraduate medical, nursing and allied health education. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:154-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge regarding palliative care amongst medical and dental postgraduate students of medical university in Western Maharashtra, India. CHRISMED J Health Res. 2014;1:250-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- A model for delivery of palliative care in India – the Calicut experiment. J Palliat Care. 1999;15:44-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding palliative care among doctors in border security force. Prog Palliat Care. 2014;22:272-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Awareness, knowledge and attitude about palliative care, in general population and health care professionals in tertiary care hospital. Int J Sci Stud. 2016;3:31-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thoughts of emergency physicians about palliative care: Evaluation of awareness. J Acad Emerg Med. 2015;14:75-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of palliative care among medical interns in a tertiary health institution in Northwestern Nigeria. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:343-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coping with Cancer. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1979.

- Effect of home care on the place of death of advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1142-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Realigning training with need: A case for mandatory family medicine resident experience in community-based care of the frail elderly. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:697-9. 704-7

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment and knowledge in palliative care in second year family medicine residents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:265-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative medicine and the medical oncologist. Defining the purview of care. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teaching cancer pain management: Durability of educational effects of a role model program. Cancer. 1996;77:996-1001.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chinese oncologists' knowledge, attitudes and practice towards palliative care and end of life issues. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude of final – Year medical students in Germany towards palliative care – An interinstitutional questionnaire-based study. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10:19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of palliative care amongst undergraduate medical students in rural medical college of Maharashtra. Natl J Community Med. 2012;3:666-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Pilot Study on Undergraduate Palliative Care Education–A Study on Changes in Knowledge, Attitudes and Self-Perception. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;5:236. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000236

- [Google Scholar]