Translate this page into:

Understanding the Organization of Hospital-Based Palliative Care in a Nigerian Hospital: An Ethnographic Study

Address for correspondence: Dr. David A. Agom, Faculty of Health and Society, University of Northampton, Waterside Campus, University Drive, Northampton, United Kingdom. E-mail: agom.david@northampton.ac.uk

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Organization and delivery of palliative care (PC) services vary from one country to another. In Nigeria, PC has continued to develop, yet the organization and scope of PC is not widely known by most clinicians and the public.

Objectives:

The aim of the study is to identify PC services available in a Nigerian Hospital and how they are organized.

Methods:

This ethnographic study, utilized documentary analysis, participant observation, and ethnographic interviews (causal chat during observation and individual interviews) to gather data from members of PC team comprising doctors (n = 10), nurses (n = 4), medical social workers (n = 2), a physiotherapist, and a pharmacist, as well nurses from the oncology department (n = 3). Data were analyzed using Spradley's framework for ethnographic data analysis.

Results:

PC was found to be largely adult patient-centered. A hospital-based care delivery model, in the forms of family meetings, in- and out-patients' consultation services, and a home-based delivery model which is primarily home visits conducted once in a week, were the two models of care available in the studied hospital. The members of the PC team operated two shift patterns from 7:00 am to 2.00 pm and a late shift from 2:00 pm to 7:00 pm instead of 24 h service provision.

Conclusions:

Although PC in this hospital has made significant developmental progress, the organization and scope of services are suggestive of the need for more development, especially in manpower and collaborative care. This study provided knowledge that could be used to improve the clinical practice of PC in various cross-cultural Nigerian societies and other African context, as well as revealing areas for PC development.

Keywords

Care delivery

hospital

models

Nigeria

organization

palliative care

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care (PC) is medical care for patients and families with progressive life-limiting illnesses, aimed at improving the quality of life for both patients and their families. This specialized care is structured and organized differently between, and within, different countries.[12] For instance, PC in the US is organized and delivered by an interdisciplinary team, mainly in hospitals.[3] There is also a hospice-based model in the US but largely nondisease-focused treatments rendered in patients' homes, inpatients' hospice facilities, nursing homes, residential facilities, and acute care hospitals.[34] Overall, PC in the UK is organized into specialist and generalist levels.[5] The specialist level provides hospital-based care led by a National Health Services multidisciplinary team and hospice care in which patients do not need to relinquish disease-focused treatment, unlike in the US.[46] The hospice care model in the UK provides care through inpatient beds, day care, home hospice, and care homes.[7] The generalist level comprises all other health-care professionals but is supported by specialist teams to provide PC services in various care settings.[6]

In Africa, there is a scarcity of research about organization of PC.[8] Specialist, district, community, and home-based care PC levels were found to be available in Kenya and Malawi.[9] In Nigeria, there is a lack of guidelines and policy on palliative and end-of-life care,[101112] implying that hospitals providing this specialized service decide for themselves on how they will structure and organize care provision. Therefore, the organization of care can vary from one hospital to another, and the model of PC may differ across states in Nigeria. A key starting point is to understand the organization of PC in the Nigerian context, because it may enhance knowledge that could promote effective collaboration between PC and nonPC practitioners, consistent with the findings by Horlait et al.[13] In Western Nigeria, PC is organized into hospital- and community-based care.[1415] No study has explored the organization and model of PC in Southeastern Nigeria. Therefore, this qualitative study aimed to understand how PC service was being organized and the kind of services available for service-users in a hospital within Southeastern Nigeria. This study could promote service utilization by the public, particularly those who may not be aware of, but require, such services.[16]

METHODS

Organizational ethnography was employed using participant observation, interviews, and a review of documentary evidence, because such an approach is recommended for understanding how actors work, act, and interact in their organization as they perform their daily activities.[17]

Participants and the setting

This study was conducted in a hospital providing organized PC in the Southeastern Nigeria. The participants were selected purposively, either based on their experience of providing PC or that they clinically engaged with those who provided PC. Therefore, all the members of PC team, comprising three doctors, four nurses, two medical social workers, a physiotherapist, and a pharmacist that work in PC unit, were included. Furthermore, three nurses from the oncology department participated in the study.

Ethical considerations

The ethical approval for this research was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Northampton, UK, and those of the studied hospital in Nigeria.

Data collection

Guided by Spradley, we conducted descriptive, focused, and selective participant observations[18] in the PC unit of the studied hospital. The daily activities and interactions of the PC teams were observed in the wards, the PC outpatient clinic, the PC nurses' station, and meetings between the patients' relatives and the PC team. Overall 387 hours of participant observation was completed from September 2015 to March 2016. Semi-structured in-depth face-to-face interviews were conducted with the 14 healthcare professionals that participated in this study. Spradley's guidance was followed during the ethnographic interviews, by asking descriptive questions, followed by structural questions and then contrast questions.[19] Each interview was conducted in English, was recorded, and lasted between 45 min and 90 min. The four documents were identified and reviewed included the admission, daily report, home visit, and follow-up registers of the PC unit.

Data analysis

Data gathered during the participant observation and review of documents were documented in the field notes, while interviews were transcribed verbatim and were stored in NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10. Data triangulation were utilized to compare and contrast the information collected from the documents, participant observations and interviews. Spradley's framework for ethnographic data analysis, comprising domain, taxonomic, componential analysis, and the discovery of cultural themes, was conducted.[18] During the domain analysis, NVivo 10 was used to aid organization of the voluminous amount of data into what Spradley regarded as “include term” and “cover terms.” Domain analysis worksheets were created and used to search for semantic relationships, in line with Spradley's procedures for domain analysis. Having identified several cultural domains (an important unit that exists in every culture) and the smaller units that constituted these domains, the relationships that existed within and among the cultural domains were organized on the basis of a single semantic relationship to form taxonomy, or what could be regarded as the cultural category. For the next layer of analysis, all the contrasts or components of meanings associated with several cultural categories were searched and organized using what Spradley named a “paradigm worksheet.” Finally, the relationships that existed among the larger set of cultural categories were examined by grouping the categories that fitted together as subsets of single ideas that connected subsystems or elements in the pattern that make up a culture to arrive at two cultural themes: care pathways for patients with serious illnesses and the organization of service provision.

Care pathways for patients with serious or life-limiting illnesses

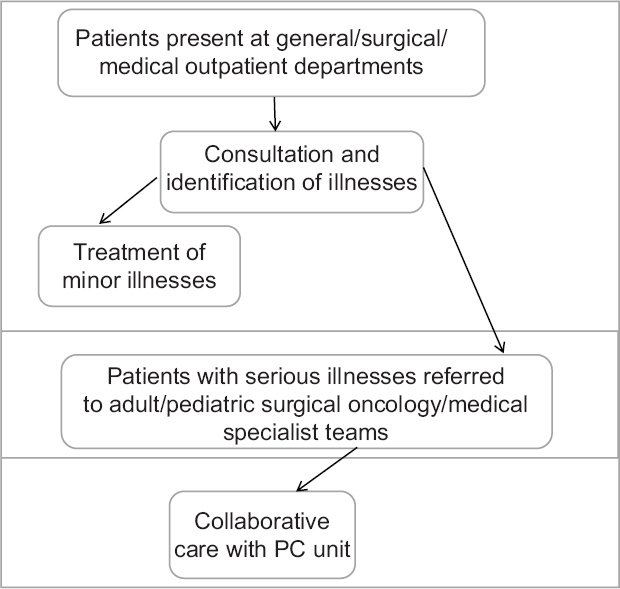

The studied hospital had a care pathway designed so that the first point of entry for all patients was through outpatient departments. At this point, the physicians assessed patients' illnesses for their severity, whereby minor illness was treated, but serious illnesses were referred to specialist teams for expert management, as shown in Figure 1. During participant observations, it was noticed that collaborative care between the PC unit and the specialist teams was at the third layer of the structural care pathway, whereby decisions regarding this collaboration were made by the specialist teams (physicians from the primary unit).

- Structural care pathway

A key feature of this pathway was that collaborative care between members of PC unit and professionals from the primary unit, for patients with cancer and other serious illnesses, were not at the same layer, but at the last layer of this care pathway [Figure 1]. Remarkably, it was consistently noted that PC was not included in the care package for most of the service-users at the point of their diagnosis and/or referral to specialist teams. This provides an impression about a lack of understanding of the benefit that could be gained from early PC. Furthermore, it was also noted that the studied hospital had no protocol or organizational guidelines for collaborative care of patients with serious illnesses, which explains the inadequacies in referrals.

Organization of service provision

The members of the PC team reported how PC was organized in their hospital. The care organization was also observed while working with members of the PC team. This has been grouped into models of PC and the shift patterns of the PC unit.

Models of palliative care delivery

During interviews, members of the PC unit explained that they undertook various aspects of care, such as home visitations, family meetings (meetings between the patients' relatives and members of the PC team), ward rounds, enrolment, and consultations:

We conduct palliative care ward rounds every Monday and Friday. During these ward rounds we go from one ward to another, providing care to our patients in various wards (Interview excerpt, Doctor 1).

We do enrolment on Tuesdays and Thursdays. We also conduct family meetings on Tuesdays and in this meeting, we provide psychological support to the patient's family. We also counsel them and inform them of what they should expect as the outcome of the patients' conditions. On Wednesdays, we visit our patients that live within the city. We are not able to visit those living in rural areas. When we visit them, we provide services like wound dressing, bathing, treat their pressure areas, and assist in their medication, provide counseling on drugs, personal and environmental hygiene (Interview excerpt, Nurse 1).

Two models of PC delivery appeared to be available in this hospital. These were first hospital-based care delivery in the forms of family meetings and in- and out-patients' consultation services, and second, the home-based delivery model (home visits) conducted once a week, usually on a specified day. The organization of home-based care implies that service-users may not have access to services when required, and this may lead to poor quality of life. Overall, these two models of care are suggestive that other models, such as an ambulatory PC clinic and hospice care models, were lacking.

In addition, it was repeatedly observed that patients were not involved in “family meetings” and that they were predominantly conducted when patients were nearing the end of life. Members of the PC team during interviews made statements that reinforced this observation. For instance:

In palliative care, we invite the patients' relatives for family meetings, especially when the patient is nearing his or her last days of life, because most of these patients are often referred late to us. We provide explanations to the family members of the patients about the prognosis and the goal of care (Interview excerpt, Nurse 4).

The predominant practice of conducting a family meeting at the later stage of the illness trajectory could be associated with the organizational cultural norm rooted in the dominant discourse of late collaborative care with the PC team. However, members of the PC team used the principle of nonmaleficence to justify noninclusion of patients in these meetings. One of the doctors said:

I have experienced some cases where a patient was depressed when she was told that her condition is incurable…from that moment, the woman stopped talking. During my ward round the next day, the sister said she has not eaten and refused to talk to anyone. Two days later, the woman died of depression (Interview excerpt, Doctor 1).

The clinicians avoided involvement of patients at these meetings due to their previous experiences, whereby patients presented some emotional difficulties. Thus, it is plausible to postulate that these professionals preferred noninclusion of the patients to deal with difficult and unpleasant reactions that may manifest during, or after, such meetings. Therefore, the members of the PC team appeared to either lack the emotional resilience or competence to directly engage in difficult conversations with patients.

Furthermore, it may be important to mention that the PC services were mostly available for adults; even the available services were sometimes inaccessible to nonadult service-users:

If you look at our enrolment record, you rarely see paediatrics receiving palliative care but there are many children in the wards with malignancies that require palliation but they don't refer to us (Interview excerpt, Doctor 1).

We don't provide care for all the children that are supposed to benefit from palliative care services (Interview excerpt, Nurse 2).

The data show that PC services were slightly available for children, indicating that this hospital may be failing in its responsibility to provide PC to improve the quality of life for children with progressive life-limiting illnesses. An alternative explanation could be that many pediatricians managed children with serious illnesses without collaborating with the PC team. In addition, while working with the PC teams, it was observed that ward rounds and PC consultation were strictly doctor led. This indicates that if a doctor was not available to lead the service provision, the patients may not have access to care. Several participants repeatedly mentioned that service-users did not receive care when a doctor was not available, which corroborated with the several observed missed PC ward rounds and consultations:

… Last week, we had many consults but no doctor to see these patients (Interview except, Nurse 1).

Most of the time, patients come here without receiving care. We are not allowed to lead ward round (Interview excerpt, Nurse 4).

These comments show that the participants acknowledged that the available PC services in this hospital were not consistently accessible to the service-users, indicating that the aims of PC may not have been adequately met. Furthermore, the comment by “Nurse 4,” above, suggests that nurses and other members of the PC team were not empowered to independently provide care to the service-users in the study setting. A physician, who was one of the participants, reaffirmed that nurses were prohibited from prescribing morphine and to independently lead PC ward rounds:

… Some nurses went for training in Uganda. When they came back they started agitating that they want to prescribe morphine because their colleagues over there prescribe drugs to their patients. We told them that it cannot work in Nigeria because medical laws preclude anyone other than a doctor to prescribe opioids (Interview excerpt, Doctor 1).

Although the preclusion of other members of PC team from leading PC ward rounds or prescribing opioids was empowered by Nigeria Medical Regulation and National Drug Policy,[20] some participants perceived that it was rooted in a persistent power struggle between doctors and other health-care professionals:

In this hospital, doctors tried to hold power on all aspects of clinical services. They try to use their power to suppress other members of the healthcare team by not allowing them to lead. This has caused some conflicts which negatively affected the care of our patients (Interview excerpt, Pharmacist Lily).

The perceived power rivalry was not obviously manifested in the studied hospital, although it may have been tacitly displayed, thereby impacting the care for patients with serious illnesses.

Shift patterns of the palliative care unit

It was observed that nurses from the PC unit had only two shift patterns, which were an early shift from 7:00 am to 2.00 pm and a late shift from 2:00 pm to 7:00 pm. It was, however, surprising to note that nurses and other members of the PC unit did not work weekend shifts (Saturday and Sunday) or night shifts:

We do two shifts in this unit. The morning and evening shifts. Our patients are provided care by other nurses at nights and weekends (Interview excerpt, Nurse 1).

We do not have specific ward for palliative care. We only do ward round and sometimes, we go back to the ward to provide support to our patients (Interview excerpt, Nurse 4).

This provides the understanding that the PC unit in this hospital arguably operated as a PC day center, although they had patients admitted to various wards. Almost certainly, the PC needs of the inpatients were not being adequately met, especially during weekends and overnight because the nurses and other team members from the PC unit did not operate a 24-h shift pattern. During the periods when the PC team members were not available to provide care to service-users, they assumed that doctors and nurses from the primary units would continue with routine medical care of their patients. This provided the insight that some critical layers of PC may not be available for patients when the PC team was not on duty. When interviewed, nurses from oncology units consistently professed that they had no time to provide psychosocial and spiritual support as the trained PC nurses would, due to their workloads. Oncology Nurse 3 said:

We do not provide emotional, spiritual and psychological care to these patients because of the workloads. Some patients already have mindset that nurses are very wicked and even when a nurse want to come close to the patient, the person will not give her attention.

The partial access to fundamental aspects of care required to improve well-being of patients with progressive life-limiting illnesses suggests that they may have not achieved the good quality of life. However, some members of the PC team repeatedly mentioned that the lack of a dedicated PC ward was a hindrance to enabling 24-h PC in the studied hospital. Although this made sense, it would be possible to organize members of their team into groups that could supervise and monitor the implementation of individualized care plans for every patient requiring PC in the various wards at all times, without necessarily having a specific ward for PC.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The care pathway leading to collaboration with PC professionals in the care of patients with serious illnesses shows that many of the service-users in the studied hospital may either have accessed PC late, or not at all, in their disease trajectory. This organizational norm demonstrated lack of early PC, despite numerous studies that have shown that PC delivered simultaneously with standard oncology care from the time of diagnosis leads to a better quality of life, reduced costs, and less futile treatment.[21222324] Lack of guidelines for effective collaborative practice was found to be a key contributor to this organizational norm; this requires further investigation.

PC was found to be delivered by few professionals and organized into two models of care similar to those that existed in other African countries,[9] although services were organized differently in the studied hospital. A summary of the kinds of services available for service-users in the studied hospital is shown in Figure 2.

- Organization of care

Importantly, the lack of nurse-led outpatients' consultations and inpatient ward rounds was understood by some participants to be a manifestation of power rivalry between the physicians and other health-care professionals. The impression about power, medical, and leadership dominance is not surprising, because there is a long history of a “latent war” existing in the Nigerian health-care system between doctors and other health-care professionals.[25] A shift to a nurse-led PC approach may be necessary in this hospital to compensate for the inadequate number of doctors available for this specialized care. Several countries, such as the UK, Switzerland, Australia, Sweden, the US, Austria, and Canada, have introduced nurse-led PC clinics, which have been shown to broaden access, reduce costs, improve the quality of care, and facilitate an interdisciplinary network of care.[25262728]

Again, there is a need to improve human resource for PC services in the studied hospital, as this will enable the availability of a 24-h PC service; in order that service-users can gain access to care that may improve their quality of life. Overall, PC in the studied hospital could be said to be majorly adult-oriented, with minimal care delivery to children, contrary to the philosophy of PC, which seeks to improve the quality of life for patients irrespective of their age. The organization and model of care revealed that both collaborative care and the shift patterns required improvement. However, further study is needed to understand other complexities about PC delivery in the studied hospital in order to generate more evidence that could contribute toward the improvement of practice. Clinical guidelines that include collaborative care with the PC team at the point of referral to specialist teams is essential, as this would encourage early PC to the benefit of patients.

Finally, given that this study was conducted in one hospital in Southeastern Nigeria, the findings presented herein cannot be generalized. However, an in-depth information from one study site is valuable in understanding this problem, thereby provided evidence for analytical and theoretical generation. Specifically, this study provided knowledge that could be used to improve the clinical practice of PC in various cross-cultural Nigerian societies and other African context, as well as revealing areas for PC development.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Professor Judith Sixsmith is appreciated for input during data analysis.

REFERENCES

- White paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe, part 2. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17:22-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance; 2014.

- Models of palliative care delivery in the United States. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7:201-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care in the USA and England: A critical analysis of meaning and implementation towards a public health approach. Mortality. 2016;22:275-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Duration and determinants of hospice-based specialist palliative care: A national retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2018;32:1322-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Models of delivering palliative and end-of-life care in the UK. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7:195-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- End of life care in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10:6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding models of palliative care delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: Learning from programs in Kenya and Malawi. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:362-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Telemedicine's potential to support good dying in Nigeria: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126820.

- [Google Scholar]

- Twenty- first century palliative care: A tale of four nations. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013;22:597-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care trends and challenges in Nigeria – The journey so far. J Emerg Internal Med. 2017;1:17.

- [Google Scholar]

- What are the barriers faced by medical oncologists in initiating discussion of palliative care? A qualitative study in Flanders, Belgium. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3873-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care in developing countries: University of Ilorin teaching hospital experience. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:222.

- [Google Scholar]

- Home-based palliative care for adult cancer patients in Ibadan – A three-year review. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:490.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care awareness amongst religious leaders and seminarians: A Nigerian study. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organizational Ethnography. London: Sage Publications; 2008.

- Participant Observation. United State of America: Waveland Press, Inc; 2016.

- Participant Observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1979.

- 2005. Federal Ministry of Health, World Health Organisation. National Drug Policy 2005. Federal Ministry of Health, World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s16450e/s16450e.pdf

- Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:834-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does modality matter? Palliative care unit associated with more cost-avoidance than consultations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:766-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Earlier initiation of community-based palliative care is associated with fewer unplanned hospitalizations and emergency department presentations in the final months of life: A population-based study among cancer decedents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:745-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical dominance and resistance in Nigeria's health care system. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47:778-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurse-led palliative care services facilitate an interdisciplinary network of care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2016;22:404-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurse-led navigation to provide early palliative care in rural areas: A pilot study. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16:37.

- [Google Scholar]

- The costs, resource use and cost-effectiveness of clinical nurse specialist-led interventions for patients with palliative care needs: A systematic review of international evidence. Palliat Med. 2018;32:447-65.

- [Google Scholar]