Translate this page into:

Epilogue: Reflections from International Mentors of the Quality Improvement Training Programme in India

*Corresponding author: Nandini Vallath, Palliative Care Division, National Cancer Grid - India, Tata memorial Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. nvallath@maxoffice.co

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Lorenz K, Dy S, DeNatale M, Rabow MW, Spruijt O, Anderson K, et al. Epilogue: Reflections from international mentors of the quality improvement training programme in India. Indian J Palliat Care 2021;27(2):235-41.

Abstract

The article collates the narratives of experiences of the international faculty who mentored the quality improvement teams from India since 2017.

Keywords

Quality

Improvement

Mentorinng

INTRODUCTION

We have seen a near explosion in palliative care-related activities in India over the past 5 years and witnessed the giant strides taken by several national level organisations, including the Indian Association of Palliative Care, in capacity building activities relevant to palliative care. The professional community has successfully initiated person-centred care services within a disease-centric health care system and has begun to explore more efficient methods to improve the quality as well as coverage of their services. Their efforts are focused initially on creating awareness, strengthening clinical competence, instilling empathy within processes and in raising funds. The phase of self-enquiry is customary to teams who have attained a steady pace of service provision, noticed the gaps in quality which were not getting resolved satisfactorily using the methods they were familiar with.

There is an ancient saying in India that the learning opportunity presents itself, when the disciple is ready and prepared. This came true for the palliative care community in India in 2017, when the missing link that is, a systematic approach to improving quality concerns became accessible through an opportune collaboration with the quality improvement leaders at Stanford Medicine. The collaboration brought in the Gurus, a team of committed mentors from renowned institutions from across the world. The Indian teams witnessed the charm and strength of genuine mentoring through this collaboration which has since continued across cohorts, until date.

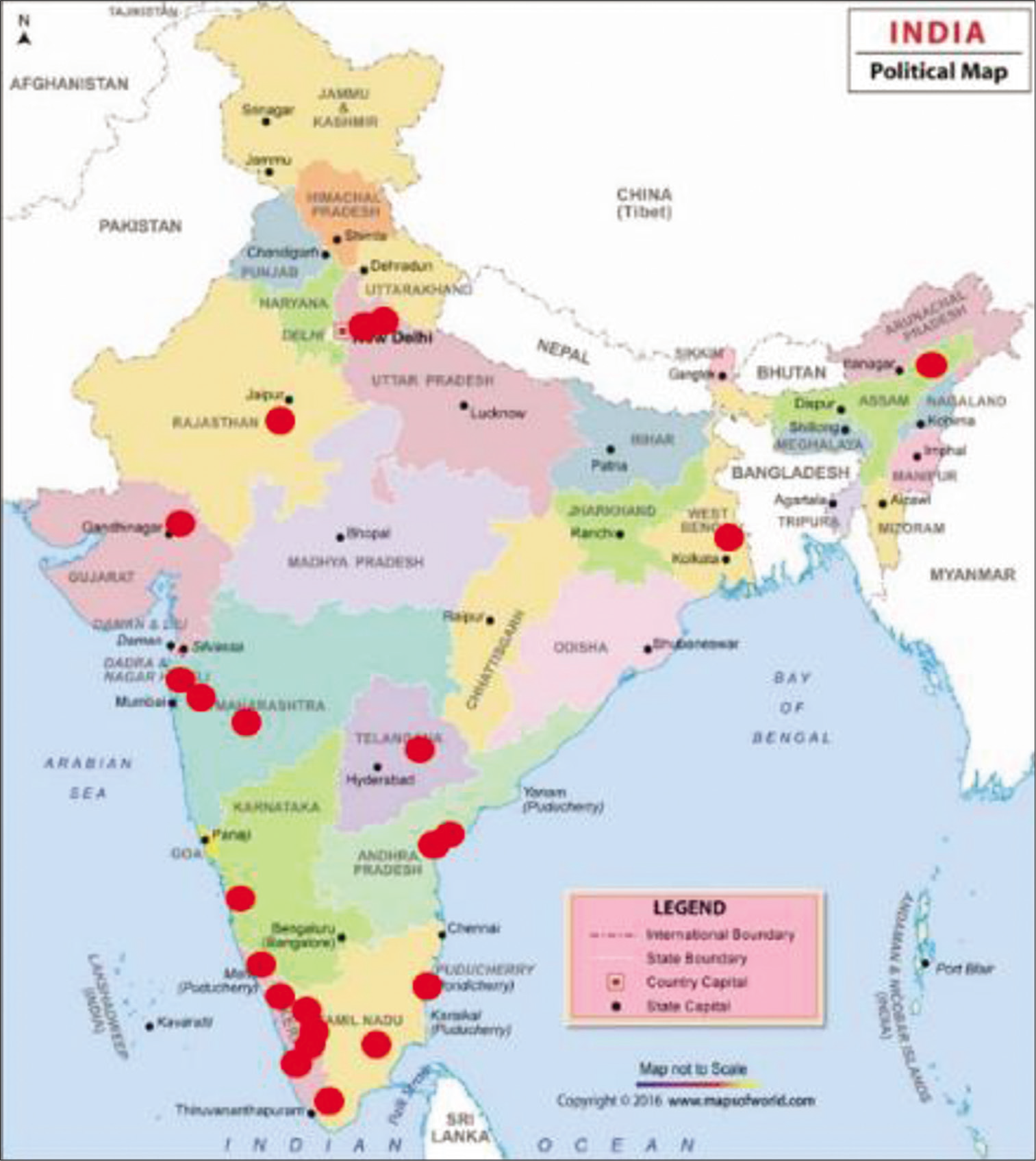

The project teams in India got an opportunity to access international mentorship during the 1st cohort. The multicentric learning collaborative that supported the quality improvement initiative spanned three continents. Figure 1 depicts the geographical distribution of hub members, mentors and the Indian team leaders, who participated in this multicentric international quality improvement collaborative.

- Geographical distribution of the multicentric international quality improvement collaborative for India participants.

Although the terms “Trainer” and “Mentor” are often used synonymously, their roles are unique. A trainer is required to get the team members skilled in a specific task. A mentor has a more informal role than a trainer, but carries several subtle possibilities to transform team dynamics and outcomes through engagement at deeper exploratory levels. The relationship is a professional one and yet, it requires a fair degree of human connectedness to reach through to the mentee’s thought processes.[1] Mentors commit to their role and this commitment includes retreating gradually when no longer required. Excellent mentors scale back their method of engagement as their mentees make progress, but they do not necessarily rush that progress if their mentee is not ready for it. It’s indeed a tough line to walk-on, but the right mentor can work well with the boundaries without crossing them. It is clear that sharing and applying proven improvement methods to geographically dispersed institutions are feasible remotely, even at an international level, and can be instrumental in addressing the most difficult of cancer care and palliative care challenges.

This special supplement is dedicated to highlight the world of quality improvement in palliative care to the readers of this journal. The articles presented earlier in this supplement described several projects completed during the 1st cohort of 2017–2018. Moreover, this article is dedicated to the reflective narratives from our international mentors who have walked alongside the Indian palliative care teams of this cohort and later with the Indian mentors and the project teams for every cohort since then. The giant leap in the capacity for quality improvement in India has been possible due to their dedication and unconditional support.

The contents below are the unabridged statements from the international mentors of the quality improvement projects in India.

KARL LORENZ

Learning Goes Both Ways!

In my experiences of serving as a mentor in PC-PAICE and more recently EQuIP-India, one of the most important lessons I have learnt as a mentor is that “learning goes both ways!” It’s true that mentors often bring specific skills, knowledge and experiences to the task of helping one’s mentees accomplish their goals. As rewarding as it is to share those insights; however, one of the most significant rewards of mentorship is learning!

One of the most important things I have learnt from my mentees is that passion is a critical ingredient in achieving change. A crucial resource that team members bring to improving care is their deep and sustained dedication. In working with palliative care teams in India, this dedication has often arisen from the compassion that clinicians bring to improving suffering. Passion is critical in even signing up for a project, but it comes into play when they revisit the challenge they are facing again and again to try to understand it better, in the strenuous efforts, they go to winning colleagues over to their perspective and in seeking out their collaboration, and in designing solutions and applying them even when unexpected obstacles arise.

A second lesson my mentees have taught me is the importance of relationships in achieving improvements. Yes, mentees have been very creative and capable thinkers, meaningfully reflective with regard to the clinical situations and challenges they’ve faced. However, as important as those qualities are, I have seen that change happens on the strength of personal relationships. I experience their interpersonal skills in the kindness, gratitude and reliability they consistently demonstrate, but they apply those same skills to win over others in their organisations – in educating them, in working collaboratively to design and implement solutions, and in sustaining the change and impact resulting from their efforts.

Finally, I’ve seen that despite the many differences in the Indian and United States health care systems, we are often struggling to change very similar things, and I’ve learnt from the solutions that teams I’ve mentored have come up with. In several cases, teams have worked to improve access to earlier palliative care in specialty settings – they’ve built alliances with colleagues, helped them identify and solve problems in a way that stakeholders find meaningful. They have patiently aligned and educated them, and codesigned processes, tools, measures and provided feedback to achieve earlier referral of patients and families in need of palliative care. Whether in ambulatory cancer care or hospital intensive care units, the problems and solutions have much in common with the challenges and approaches we follow in the United States.

In summary, mentoring has been deeply rewarding, some of the most important of which are the inspiration and insights gained from those who I have been asked to mentor. They are my best coaches!

SYDNEY DY

Learning the skills of quality improvement in palliative care is a process requiring rigor, collaboration and lifelong practice. As palliative care becomes more established in India, lessons from other countries can be valuable, on how they have moved from nascent programmes toward substantial improvement; their approach in responding to the multiple challenges of integration, increasing access and staff and their constant endeavour to improve the quality of palliative care processes of care.

The PC-PAICE collaboration structure was based on a number of key principles of good quality improvement, embraced by the international mentors and our Indian colleagues. It engaged the teams with improving quality, rather than simply expanding programmes; very carefully defining and exploring the problem, rather than jumping to solutions; choosing and documenting measurements carefully; developing contextual team-centred solutions; fostering key collaborations while focusing and refocusing on a single, manageable problem and learning and redirecting the project as it developed, depending on the changing environment, successes and failures and stakeholder inputs.[1]

“Managing up” is valuable to guide mentors in how we can best be helpful; while enthusiasm, focus on the goals and solutions and completion of tasks are valuable attributes of mentees.[2] The high quality of the participants and equally high quality of guidance provided to the mentees in this collaborative reflect successful traits in the learning relationship. Excellent mentees come to a learning partnership prepared with their questions and how their mentors can best help them. Great mentor-mentee relationships involve developing shared goals for both the collaboration and the project; eliciting and embracing feedback from both sides and being prepared and respecting each other’s time.

Finally, while recognising that achieving change in care processes are extremely hard, the PC PAICE experience emphasises the value of collaboration; and listening to different perspectives as imperative for meaningful, effective improvements. As mentors and mentees, we needed to stay open to different perspectives and circumstances and to try different approaches to grow together in nurturing partnerships. In quality improvement, we often have many ideas, often from our own experiences, but need to tailor the solution to the local project and context and support the team when interventions do not improve the situation as expected. Mentors really needed to spend time learning about the mentees and the local context. Many of the innovative lessons learnt were helpful for us to bring back to our own countries internalising the novel perspectives and considering more outside-the-box approaches within our own health care systems.[3]

MICHELLE DENATALE

Those in health care today are faced with on-going pressures to find a way to deliver high-quality care in a low-resourced environment. Clinicians crave for knowledge to solve problems they encounter at the health care system level, but lack the skills, tools and dedicated time to do so. Both the PCPAICE and EQUIP learning collaborative provided a venue where teams from across the globe could come together under a common goal and train in the core fundamentals of quality improvement and implementation science.

To kickstart this effort, QI teams were formed with a composition of front-line physicians, nurses, clinical assistants and a designated mentor. The role of the mentor was to partner with the team leader to reinforce the didactic training and demonstrate use of the QI tools such as the standard A3 thinking using process maps, cause-and-effect diagram, data collection, analysis and monitored interventions. The mentor’s role was to guide the QI team to select a goal that was Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time bound – often narrowing the project’s scope to ensure the project would have a measurable impact and ultimately be able to replicate their success in another venue if successful.

As a team mentor, there were several lessons learnt from coaching team members who were new to quality improvement and improvement science. First, I would think a few steps ahead of the team anticipating questions or issues that may arise during our monthly touchpoint calls. When data collection became difficult to interpret or the QI team would face resistance from their colleagues, I was able to encourage the team to testing their ideas and not be afraid to fail. Second, I would work with the project leader to ensure their local leadership sponsored the team’s work and efforts, encouraging them to meet quarterly with them to provide a status report of their work. When the sponsor would see the methodical approach in which the problem was presented on an A3 worksheet – they were more likely to engage and remove barriers to implementation of the team’s ideas. It was important to gain recognition from the local leadership when the team’s efforts successfully completed their project. This became a key to receiving further support to continue with improvement plans for the quality of care being delivered.

As a mentor of both the PC-PAICE and EQUIP cohort, I had the opportunity to see first-hand how challenges we face in palliative medicine in the United States are quite similar to those in India. When participants selected projects as part of the EQUIP cohort, common themes that I experience in the US health system reoccurred as several Indian sites – including the adoption of standard care pathway, improving access to care and limited resources, improving the patient experience and reducing wait times or delays. After coaching many teams in this collaborative, I walked away from each experience valuing the growth of a professional community in India that is, competent in quality improvement and greatly hope that many of the project team members will become future mentors in this work.

MICHAEL W. RABOW, MD

While there is danger in stereotyping across cultures, and certainly caution is necessary in generalising from individual experiences, my work as an international mentor in the PCPAICE programme has led me to three promising observations.

First, from my perspective as an US academic palliative care physician, I found my mentee colleagues from India to demonstrate a wonderful combination of supportiveness and honesty. The individuals on the team supported each other with enthusiasm but also were able to offer and receive straightforward and honest feedback from each other. This collaborative approach was very effective in moving through the quality improvement process. The well-intentioned directness of my mentees contrasted with my American experience of “political correctness” and indirect communication. I found it quite refreshing and super helpful in the fundamental processes of QI work: Creativity and rapid, evidence-based evaluation of hypotheses – “is it so?”

Second, I believe the benefits of mentoring flowed in both directions. I hope my perspective was helpful to my teams, but I was also excited to learn from and be inspired by my mentees. As a mentor to Indian teams, I found myself often questioning my own assumptions about what was possible and what was beneficial. This “comentoring” has led me to expand my understanding of what palliative care is and has led to friendships and opportunities to support each other at international education events and academic conferences.

Third, my PC-PAICE experience impressed me with the fundamental need and opportunity to continue to promote the QI process in Indian palliative care. This is partly due to the fact that the Indian teams are so committed to the learning and the process and partly due to the incredible potential for impact across the massive scale of Indian health care.

ODETTE SPRUIJT

In the Australasian Palliative Link International – APLI’s Project Hamrahi, a “mentor” is defined as a “fellow traveller,” seeking to expand one’s personal understanding of palliative care in a new and unfamiliar setting, by accompanying local palliative care providers who are pioneering the development of palliative care in their local setting. The mentor in the Humrahi context brings expertise and knowledge about palliative care in a developed country setting, and seeks to collaborate with the local palliative care providers in adapting those practices to the local needs and circumstances. In this way, as much as the mentor is an adviser, counsellor and teacher, so the local provider is an adviser, counsellor and teacher to the mentor. This mutual learning and development is the essence of the Project Humrahi relationship.

This spirit of sharing expertise and learning from each other was present in the quality improvement project initiated by Stanford University Palliative Care department and Clinical Effectiveness Leadership Training (CELT) programme in collaboration with Indian palliative care providers and a group of like-minded international palliative care and research colleagues.

The first round of this mentorship saw all participants carefully navigating the cross-cultural interactions, mastering unfamiliar quality improvement terminology, concepts, processes, run charts and measurement tools. Stanford’s teams patiently led the collaborative. Their respectful attitude and encouragement set the tone for learning and sharing. I shared the first mentoring role with an Australian colleague and we often brainstormed through email and video calls, about how we might better assist the project teams in India, who were facing many challenges in the QI project. I felt better prepared for the second round of the programme and by the time I was invited to join as mentor to the third QI team in India, the familiarity and confidence with the programme were very evident to me.

Each linked team has chosen very different quality improvement projects. The learning from other teams in each cohort was not only a powerful tool in this collaborative, but also a positive experience and incentive. Participants celebrate each other’s successes and spur each other on. The presentations at the graduation ceremony each year have been a highlight for me, not to be missed and to be savoured.

The sign outside the Aarohan Civil Service Institute in Guwahati, India, said “Mentoring is a brain to pick, an ear to listen and a push in the right direction” attributed to John C Crosby. PC PAICE/EQUIP-India programme is definitely a push in the right direction for me as an invited mentor also and one I am very grateful to have participated in.

KAREN ANDERSON

“What counts is not the enormity of the task, but the size of courage.”

Matthieu Ricard

The courage displayed by everyone involved in the EQuIP India/PC-PAICE research project I have experienced was enormous. The project straddles across different continents, various cultural communities, a range of identified diverse projects and skill sets of the participants while all engaging in connecting using assorted technologies. A profound task which initially both excited and aroused interested curiosity in me.

The Stanford University Palliative Care initiation of the project and the CELT team’s introduction to and training in current quality improvement education has been a valuable learning and life experience. Being part of the EQuIP India/PC-PAICE research project has offered me several meaningful observations.

First, there has been a dual benefit throughout all three projects. As a mentor I learnt incredibly from the others I worked with especially regarding encountering different contextual challenges. The Indian project team members were open and available to receiving honest feedback and confidently shared their concerns at all stages throughout their projects. This enabled appropriate ways to approach the challenges and discuss ideas with ease. This was particularly evidenced during the first QI project which I shared with an Australian colleague and which faced significant organisational and systemic issues. Despite these issues being present, the Indian project still reached a useful completion.

Second, the collaborative comentoring was illuminating and rewarding. I comentored with an experienced palliative care physician in India during the second and third projects. It was helpful being able to be backed up by each other, when either of us had other commitments intruding upon a planned feedback session with our project team members. Bringing our different training perspectives of medicine and psychosocial care together in our shared mentoring roles seemed to be advantageous to both projects.

Third, it was a real pleasure and delight to observe and witness the growth in confidence of my Indian colleagues. It became evident as the projects developed that involvement in the QI projects resulted in an expansion of knowledge, understanding and confidence.

On reflection, participation in these projects has also enabled powerful learning across the different cohort projects. During the full Team Meetings and the final project Graduation Presentations, I appreciate the tremendous learning that was acquired. This learning from all projects, together with the more specific quality improvement concepts, project tools and strategies, has been enriching and extremely worthwhile.

MEERA AGAR

“A corporation is a living organism; it has to continue to shed its skin. Methods have to change. Focus has to change. Values have to change. The sum total of those changes is transformation”

Andrew Grove

Is it time for an international effort in quality improvement in palliative care?

The most significant observation from my involvement in the PC-PAICE is the universality of the challenges faced by palliative care services regardless of where you are situated in the world or the resources you may have. PC-PAICE is a delightful exemplar of how honesty, generosity of spirit and the strive to do better for our patients, both from mentees and mentors alike, is truly transformative. Sometimes, the crucial step in solving problems is to realise that you are not the first, and indeed won’t be the last to face the challenge. My observation is that internationally, we face universal challenges in the drive to improve quality of life across the illness trajectory and diagnoses, across settings and to integrate core principles of person-centred care into our daily work.[4]

Quality improvement is relational work. Quality improvement asks us to question the circumstances and settings of care provision. As a mentor our role is often to bolster courage in our teams to reach out to someone who is a critical piece of the jigsaw and to “practice” how to have the conversation to get that person on board. The other role is to provide for the team members a “voice over their shoulder,” providing gentle challenge to the assumptions that may be made or rush to jump to solutions. Through doing this for others, fundamentally, it enhances the mentor’s ability to challenge their own assumptions and question themselves. Witnessing the evolution of our team’s projects has often refreshed my energy to tackle the improvements needed within my own practice. The “ah hah” moments in our teams really bring the most joy – when they realise that they can let go of the pre-configured solutions and let the solutions appear through the exploration. This is the transformative moment. As mentors we get to hear of the subsequent excitement when they see results; and no matter how many teams you mentor the significance of this still always takes you by surprise.

After 3 years of mentoring Indian teams, I am convinced that the fortitude, resolve and shared learning of an international collaborative to improve quality in palliative care have much to offer the sector.

CONCLUSION

The former improvement training named PC-PAICE has now evolved into an India-based improvement resource (QI Hub, India) and training programme called “EQuIP India,” meaning “Enable Quality, Improve Patient Care.” Capacity building for health care improvement and mentor development are the key objectives of the QI Hub offerings.

An online learning platform supports the teaching schedule organised by the Stanford and India Hubs and the coaching of Indian project teams with their mentors. This platform is hosted by the National Cancer Grid in India, a globally recognised resource. The platform currently (i) facilitates health care improvement training, (ii) shares improvement project updates for institutions across the country and (iii) hosts a mentoring forum for the professionals interested more deeply in the improvement science. In the future, access to evidence-based tools and templates for the application of improvement science will also be featured on this platform.

After 3 years of offering this training and mentoring, 22 teams in 11 states in India are now trained in health care improvement science [Figure 2].

- The 22 teams in 11 states in India trained in quality improvement science.

The number of patients directly impacted by the completed projects is in the thousands, and as the years go by, millions of patients will access better care due to continued capacity building in achieving patient-centred improvement project. Furthermore, budding quality improvement leaders access the EQuIP resources to build skills and prepare to serve as mentors or improvement leaders for their local organisations. Newly trained Indian mentors now engage as coaches to subsequent project teams. Some of them are leading the creation of improvement hubs at their local institutions.

We at the Quality Improvement Hub of India salute our mentors for their commitment and generosity of spirit!

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- What Is the Difference Between a Coach a Trainer, and a Mentor? Available from: https://www.integrify.com/blog/posts/difference-between-a-coach-a-trainer-and-a-mentor [Last accessed on 2021 Aug 03]

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality improvement pearls for the palliative care and hospice professional. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:758-65.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- What Mentors Wish their Mentees Knew. 2017. Harvard Business Review. Available from: https://www.hbr.org/2017/11/what-mentors-wish-their-mentees-knew [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 10]

- [Google Scholar]

- Unsettling Lessons Learnt Trying to Make Healthcare Better. 2020. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sachinjain/2020/05/23/12-unsettling-lessons-learnt-trying-to-make-healthcare-better/#6f8e977861ea [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 10]

- [Google Scholar]