Translate this page into:

Battling Alone on Multiple Fronts – How Gender Norms Affect the Soldiers’ Wife as Caregiver in India

*Corresponding author: Savita Butola, Border Security Force, Sector Hospital, Panisagar, Tripura, India. savitabutola@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Butola S, Butola D. Battling Alone on Multiple Fronts – How Gender Norms Affect the Soldiers’ Wife as Caregiver in India. Indian J Palliat Care 2024;30:222-31. doi: 10.25259/IJPC_79_2023

Abstract

Objectives:

Women form the backbone of caregiving in palliative home care throughout the world. They put in more intense care for longer hours, perform more intimate tasks, and face more physical and mental strain, comorbidities, anxiety, and depression. However, gender norms that perceive caregiving as a natural part of femininity dismiss this as part of their duty toward their family, thus making their care work invisible, taken for granted, and devalued. This results in women bearing more burden with less support and no appreciation and suffering more negative mental and physical health outcomes than men. Globally, women perform 76.2% of unpaid care work. India ranks a dismal – 135 out of 146 countries in the 2022 Gender Gap report. Less than 10% of Indian men participate in household work. Women in rural India continue to be less educated; the majority are not allowed to travel alone and are culturally not involved in decision-making, which is done by the males. Wives of armed forces personnel are forced to live without their husbands for long periods. This leads to even more challenges when they also need to take care of patients with life-limiting illnesses. No study has been done on this population till now. This study aimed to explore the experiences of the women in armed forces families, caring at home for patients with palliative needs.

Materials and Methods:

This was a qualitative study based on a thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with adult caregivers – either serving personnel or their dependent family members.

Results:

Female relatives were the main caregivers in 13 cases; the majority belonged to rural areas, were between 22 and 47 years of age, most were married, had young children, and reported health issues of their own. Major themes that emerged include lack of information, the expectation of being a caregiver irrespective of ability/needs, physical and psychological burden, neglected emotional needs, difficulty in traveling alone, social isolation, loss of employment with the financial burden, stigmatisation and ill-treatment of widows by in-laws.

Conclusion:

‘Soldier’s wives, who must stay alone, face increased burdens as they face not only the physical and emotional burden of caregiving but also the additional challenges of living alone, mostly in rural Indian society, where gender norms are still deeply ingrained. Creating awareness about this vulnerable community among palliative care providers is required to improve services for them. There is also an urgent need for identifying, challenging, and addressing stereotyped roles and disparities in healthcare systems, practices, care goals, and policies by sensitising staff, educating families, developing gender-sensitive resources and support systems, initiating care discussions, and undertaking more gender-related research.

Keywords

Palliative

Caregiver

Armed force

Gender

India

INTRODUCTION

Women, the backbone of caregiving in palliative care throughout the world, are primary caregivers for the sick and dying. They help with feeding, toileting, bathing, medication, comfort, companionship, and emotional and social support.[1] Caregiving comes with emotional and physical costs, experienced differently by men and women[1], because the prevailing culture and gender norms dictate how people perceive and experience their roles in life. Gender affects not only the caregiving experience but also impacts caregivers’ mental and physical health.[2] Gender, a social construct, is defined as the ‘roles and behaviours which are socially prescribed within a particular historical and cultural context and determine how the concepts of masculinity and femininity are constructed and evolve.’[3] It is, therefore, different from biological sex – ‘the difference between females and males due to chromosomes, sex organs, and endogenous hormonal profiles.’[4]

Gender affects why and how people care.[5] Gender norms dictate that women do household work, bring up children, and take care of the sick. Women do most of the caregiving, yet the perception of nurturing as a natural component of femininity[5] makes this work unacknowledged, devalued, taken for granted, and often obscured by the euphemism ‘family care.’[1] Androcentrism, in biomedical research has further invisibilised women, assimilating them to men.[6]

Globally, women perform 76.2% of unpaid care work, more than thrice as much as men. The average for men – 31 min or 7.9% is the lowest in Asia-Pacific.[7] India ranks dismally- 135 out of 146 countries in the 2022 Gender Gap report.[8] Less than 10% of Indian men participate in household work,[9] spending an average of 19 min compared to 298 min by women.[9,10] The existing literature on caregiving shows that more women than men are negatively affected, with a higher risk of stress, anxiety, and depression and more unmet psychosocial needs as a result of providing higher and more intense levels of care.[5]

A particularly vulnerable group in India is women in service families, who have to live alone for most of their lives in a deeply patriarchal society. Armed forces life is very different from civilian life, with its distinctive lifestyle. The men live in barracks on campuses, where accommodation for families is limited and allotted in rotation to a fixed number for a limited time. Deployment in difficult terrain, remote areas far from home, with a high risk of disability and death, frequent relocations due to unpredictable frequency and duration of outstation duties, and transfers every 2–3 years characterize forces life. The families might get campus accommodation for a year or two, but distance from native places, children’s education, or aged, sick parents may require wives to stay back. The personnel get only 2 months’ annual leave to visit home. Some wives may not get to stay with their husbands throughout the service period. The changing social structure has dismantled the joint family system, where the younger and older members could support each other, and led to more wives being left to manage alone. Some stay in rented accommodation in cities for children’s education. The families staying within campuses get organisational help but those staying outside get neither the safety and security of campuses nor the support of extended village clans. Managing all this in the husband’s absence in rural India, where gender norms are deeply ingrained, puts the soldier’s wife at a double disadvantage as a caregiver.

To date, there is no published literature about the experience of Indian soldiers’ wives as caregivers. A search in PubMed, EMBASE, and CINAHL revealed nil results. This study strives to fill this knowledge gap. The aim was to explore how gender norms affect women caregivers in service families.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The methodology was a qualitative exploration through a ‘thematic analysis of interviews.’ Statistical procedures of quantification fall short when ‘trying to understand processes and phenomena’ or the variety of human experiences. The subjects were caregivers of patients – either serving personnel or dependent family members from the Border Security Force – an armed force of India, who received palliative home care within the past 3 years. Table 1 lists inclusion and exclusion criteria. Semi-structured interviews were chosen for data collection, being more suited to exploring the experiences across illness types and age groups, throwing up a large amount of information. The open-ended questions may not be in any specific order, and each interview may have questions informed by the previous one. Focus groups were not used as people may find it difficult to express feelings publicly. An in-depth study with fewer subjects might not have sufficed the study’s wider aim.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Adult carers (aged more than 18 years) of patients with the following conditions: Carers – defined as ‘People who may or may not be family members, are lay people in a close supportive role, who share the illness experience of the patient and undertake vital care work and emotional management’.[2] Palliative care and caregiving by family/care by the personnel from the unit are considered as starting from the time of diagnosis

|

Those who were:

|

|

|

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, AIDS: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The research involved purposive sampling, commonly used in qualitative research where information-rich cases are needed or when time and resources are limited. This is a non-probability sampling technique, also known as judgemental sampling, where participants are selected due to their having required characteristics, that is, ‘on purpose.’ Since the selection and identification of cases or events depend on the investigator’s judgment, it may suffer from observer or detection bias, where the researcher’s prejudices, opinions, or expectations can affect the perceptions or observations.

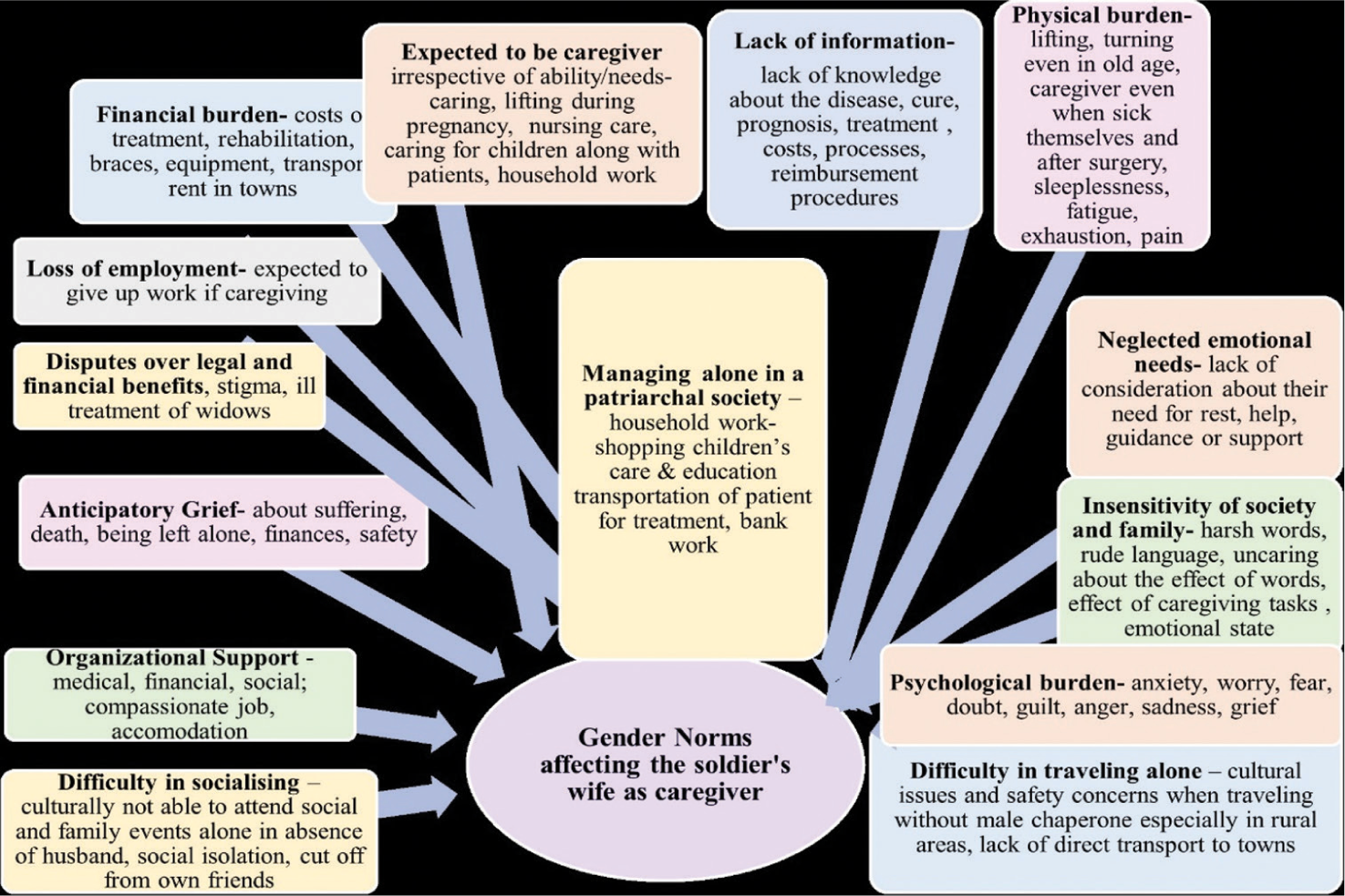

After obtaining ethical approval, eligible beneficiaries were listed and invited to participate through letters. Fifty subjects were invited. Twenty-one agreed, and six later dropped out. Bilingual information sheets in Hindi and English were provided. Informed, voluntary, and written consent was obtained. Participants could refuse participation anytime without negative outcomes – especially important as armed forces, being hierarchal organisations, are ‘vulnerable research subjects’.[11] A ‘distress protocol’ was established to support distressed participants. The date, time, and language of the participant’s choice were decided in advance, through phone or email, and interviews were conducted at their residences to ensure comfort. The literature search informed the interview guide, which was piloted and meticulous field notes recorded. Interviews were conducted over one or more sittings and recorded digitally. The narrations were recorded uninterrupted; questions were asked only as per the pre-decided format [Table 2]. The average duration was 90 min. Anonymized data were stored confidentially under triple-layer security. Ten to 12 interviews were considered optimum as the study – an MSc dissertation had a time limit. However, new themes were still emerging after 12 interviews. Data saturation occurred after fifteen interviews. Data were translated from Hindi to English and transcribed verbatim to ensure exact transcription and documentation of non-verbal communication and finer nuances. A school teacher proficient in both languages checked the soundtracks and transcripts through linguistic evaluation and back translation for accuracy. For analysis, each transcript was read numerous times. The important comments, thoughts, and reflections, highlighted and noted in the margins, formed descriptive codes. Themes were found by color-coding, listing chronologically, grouping codes into categories, and identifying common points between themes to find super-ordinate themes. These were perused twice more to ensure a complete representation of interviews, and finally, the major themes listed [Figure 1].

| Name Sex Age Address Educational qualification Occupation Address Telephone no. Name of patient Relationship to BSF personnel IRLA/Regiment no. Unit Diagnosis Year of diagnosis Year of death

|

BSF: Border Security Force, IRLA: Individual Running Ledger Account

- Thematic map.

The researcher has served in this organisation for 24 years, with an in-depth understanding as an insider. However, preconceptions were also bound to occur. Interviewer bias was most significant here. The effect of the interviewer’s own rank on the participants could not have been entirely eliminated but effort was made to minimize it by interviewing subjects in their own homes, in civil dress, to maximize their comfort. Recall bias was avoided through accurate data recording. Additional insight into responses as a result of own experiences helped further exploration during interviews. Internal validity was ensured through member checking by three subjects after completing the analysis.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Females were main caregivers in thirteen cases

Ten were aged 22–47 years; three were sexagenarians

Eleven were married, two were widows

Ten from rural areas

Eleven were wives/daughters-in-law; two were daughters

Ten had young children (4 months–14 years)

Three were pregnant. Ten reported their own health issues.

Major themes reported

Lack of information

Expectation to be a caregiver

Physical burden

Psychological issues

Neglected emotional needs

Managing things alone

Social isolation

Financial burden

Stigma

Ill-treatment

Organisational support.

DISCUSSION

The majority of caregivers were women – a fact already established in the literature. Social norms assume that it is women who will take care of men, irrespective of their ability to do so. Williams et al. state that: ‘The expectation that older women will provide end-of-life care even when experiencing considerable burden is an unacknowledged outcome of gender norms.’[1] A systematic review on gender and family caregiving found that: ‘Women caregivers experienced a greater degree of a mental and physical strain than male counterparts, linked to the societal expectation of women providing a greater degree of care.’[5] Females have significantly lower self-esteem and suffer more negative impacts on schedules and health than males.[12] This assumes greater importance in the soldiers’ wives, who stay alone for most of their lives.

Lack of information

Eleven participants reported unmet needs for information about diagnosis, prognosis, course of illness, treatment options, rehabilitation, equipment, medication, diet, costs, nursing procedures, homecare, referral, and reimbursement procedures [Table 3] [Item i]. The accounts support what is already known about women’s autonomy in Asian cultures. Information is not shared adequately with women, who rarely have decision-making authority. Health professionals also prefer communicating with males. Guidance for advance care planning or completing financial and legal work is seldom given. Decisions are made by husbands, sons, or other male members, usually without consulting women. A study by Chaturvedi et al. reveals how gender affects communication and collusion.[13] Another states that decisions were made without women’s participation in approximately half (48.5%) of Indian households.[14] All this hinders their ability to care effectively. Even when educated and working, women are considered individuals to be protected and sheltered, not consulted. Having internalised these norms, women also consider it normal as well as convenient to defer autonomy to male family members.

| i. | Lack of information | Caregiver 2 Page 1, Line 2, 3, 20, 21 ‘My husband was HIV positive. I had no idea of his illness. It was only during his last days that I came to know. No one told me, Neither my husband nor the staff’. Caregiver 4, Page 3, Line 11, Page 5, Line 7–9 ‘No-one told me – but they had told my husband that the baby was getting fits. No-one told me the real problem. I, however, had doubts – God knows what is the condition of the child. They are hiding something from me…there is something in the matter. I had to search on the internet’. |

| ii. | Expected to be caregiver irrespective of ability/needs | Caregiver 14, Page 2, Line 7–10, 23–24;P 4, L 32, P 5, L 1–3, 15, 16 ‘Mother falling sick and my wife becoming pregnant and parents shifting in with us, everything happened simultaneously. Being a son, I used to hesitate but my wife learnt all these things-how to change the catheter, how to perform suction, how to give injections, how to feed her through the tube, how to change the diaper, how to clean the tracheostomy tube. Home nursing was very expensive but in just fifteen days, my wife learnt it. My elder daughter is now 10 years, younger is 4 months. Wife is busy taking care of my parents as well as children. First 3 months of pregnancy were tough but she managed her complications and also started caring for mother’. Caregiver 9, Page 5, Line 9–10, 16–17 ‘My daughter looked after my wife alone. My wife’s biggest worry was – ‘Who will lift me up and take me to the hospital? I can’t walk. How will our daughters lift me?’ Caregiver 15, Page 6, line 22,23 ‘My daughter has to take care of the household work. The time meant for studies is wasted in this’. |

| iii. | Physical burden | Carer 1, Page 6, Line 1–6 ‘My mother would sit with him the whole day and throughout the night. He’d tell her to massage his head or press his legs. She’d always be doing something to make him comfortable. For her, there was no rest’. Caregiver 3, Page 17, Line 12–19, Page 21, Line 26–29, Page 22, Line 11–13 ‘She was also an old lady. Being by his side, she would help him up but, all her joints would start creaking. He was quite heavy. She would be up the whole night with him. She was almost 70 years, having multiple age-related problems-high BP, hypothyroidism and had been operated 4–5 times – for disc-prolapse, uterus had been removed. He would be up the whole night and keep telling her – ‘Turn me over. help me sit up…take me to the bathroom…take me for potty… do this… do that’ Then he would sleep in the daytime but she could sleep neither at night nor during the day’. Caregiver 4, Page 11, Line 19–20 ‘Now that I have conceived, I can’t carry him. I start having pains. In future, more problems will come up. So how will I handle him in that condition, I am tense about that’. Caregiver 13, Page 5, Line 22–24 ‘It was physically and mentally exhausting. Sending the daughter to school, getting her homework done…lack of sleep, cooking, cleaning, washing and feeding mother as well as the infant’. |

| iv. | Psychological burden | Caregiver 2, Page 3, L 1–3 L 14–16; ‘When I learned he was HIV positive, I could not get up for two days from the shock. Kept crying. My eyes were swollen. Was in a very, very poor condition. My whole life was shattered. I thought of what will my children do? Who will take care of them?’ Page 13, Line 21–23 ‘I had lost the will to live. I would rather be dead than go through all this. I thought of all the ways one could commit suicide’. Caregiver 5, Page 18, Line 17–19 ‘If something happens to us, who will take care of her? We think of that… worry a lot. Today we are there, but after us? My wife often sits and cries’. |

| v. | Insensitivity | Caregiver 2, Page 4, Line 8–10 ‘People would deliberately ask again and again, even when they knew it was HIV – ’What disease does he have? Why don’t you tell us the name of the disease he has?’ |

| vi. | Neglected emotional needs | Caregiver 4, Page 18, Line 10–13, 17; Page 19, Line 12 ‘Husband has at least his family to support him, I have no one… Even if I talk to my parents, they tell me that it does not matter. ‘Your husband has to meet his relatives. He has come on leave, let him go. It doesn’t matter’. No one understands me, and no one wants to understand. Other than loneliness, there is anger and frustration’. Caregiver 4, Page 24, Line 33–35, Page 25, Line 1–5 ‘It was just ten days ago that I had the miscarriage. After 1 or 2 months, that baby would have been in my lap so I was feeling that my baby has died but everyone else is enjoying. My husband was not at all upset…was having drinks with his friends and I was asked to cook non-veg and serve them. That really hurt… (in tears) Since then, I have stopped having any expectation from my husband also. How could he enjoy like this-it was not even ten days…and they were having a party at home… drinking… asking me to make lemon chicken…and this and that-I could not sleep the whole night… kept crying and crying… The day the miscarriage took place, I was alone and nobody even talked to me. My husband did not even talk to me as if, as if …somehow it was my fault. At that time, I felt that you are all alone in the world and whatever you have to do, you have to do it all alone by yourself. And that is something I have not forgotten till today’. Caregiver 6, Page 11, Line 2–5, 14–15 ‘My In laws had stopped talking to us. None of them would even ask us how we were’. |

| vii. | Managing things alone in absence of the husband | Caregiver 4, Page 3, Line 33–37 ‘We needed fully trained occupational therapists so we shifted here. I had to manage everything on my own – physiotherapy, speech therapy, hippotherapy, hydrotherapy – all these, for the last 4 years, I am getting it done’ Caregiver 1, Page 7, L 30–32 ‘When my father died…I was in the unit and through the illness my wife managed alone…whatever last rites and rituals were to be done, I did that and went back to the unit…mother and wife were left alone’. |

| viii | Difficulty in traveling alone | Caregiver 1, Page 3, L3, 4 ‘Only mummy, missus, were there at home. Whenever he had to be shown to a doctor, one male would be required to accompany them to the hospital’. Caregiver 12, Page 3, Line 3, 4, 8. 9 ‘They called for review after every fifteen days. My wife used to carry him to the hospital every time. It was very difficult. It is 2½ h’ distance from my home – then one has to change two buses and then travel by auto-rickshaw carrying him’. |

| ix. | Difficulty in socialising | Caregiver 8, Page 21, Line 14–26 ‘Recently, we went home to attend a wedding; the 1st time in 22 years of service. We met so many relatives for the first time. We aren’t able to fulfil social and family obligations. As a result, people remain cut off from us. If they remain cut off, they will not support us’ Caregiver 4, Page 6, Line 23–28, Page 13, Line 2–6 ‘Life comes to a stand-still. For the last 5 years, my life has stopped. I have no personal life. I never go to visit any relative. Neither do I have any society. No friends – Nothing. Only he is there (pointing to the son). I carry him to the hospital and back home. From home I go back to the hospital again. If you see my mobile list also, there are doctors, not friends…’ |

| x. | Loss of employment financial burden | Caregiver 13, page 8, Line 24–27 ‘My mother had a stroke and became paralysed when my wife was in early pregnancy. I have two small children and my wife is managing everything on her own. She had to give up her teaching job’. Caregiver 4, Page 13, Line 22–27 ‘I was teaching before he was born. So when his problem started, I left my job. And then I though many times that I should join back but I can’t join back because there is no one to take care of him like I do. I was a lecturer of history. What is the use of all my studies?’ |

| xi. | Disputes over legal and financial benefits | Caregiver 8. Page 23, Line 9–11 ‘Sometimes the wives’ names are not entered into the service record or provident fund and pension nominations. Often a young bride is turned out by her in-laws to avoid giving a share in the property. Caregiver 2 Page 6, L 25–28 ‘When the men from my husband’s unit came to settle the financial benefits after he expired, my sisters-in law told them that she is HIV positive-will not live. Whatever financial benefits are there, they should be given to our mother or to us, not to her. The BSF representatives said that as per documents, I was the recipient. It was only after my aunt, a teacher and the self-help group at the ART Centre threatened to hold a demonstration in the village, that they allowed the unit men to meet me and complete the paper work’. |

| xii. | Stigma | Caregiver 2, Page 3,18–20, 22–23 ‘I felt ashamed of telling anyone about it. Some people in the village got to know. They would give strange looks. I would step out of the house only after it was dark’. Caregiver 6, Page 11, Line 2–5, 14–15 ‘None of the in-laws have helped. My brother-in-law – his wife would not let him talk to us. They believed that if they talk to us… like my husband had cancer, so they would also get it or we would ask them for money. My in-laws never combed my poor children’s hair when I had to leave them alone at home. They did not ever wash or bathe them’. |

| xiii. | Ill-treatment by in-laws | Caregiver 2, Page 5, Line 17–18, Page 6, Line 18; Page 14, Line 18–19 ‘(In a choked voice). After he died, they harassed me. They would tell the relatives-‘Don’t know where she has been wandering to pick up his disease. They had a problem only with me. He was their brother. He could not be in the wrong. He was not at fault. They would gossip about me endlessly’. Caregiver 2, Page 8, Line 14–17 ‘I have become forgetful. I hesitate when saying something. Earlier I had the confidence to do anything. My in-laws literally drove me mad. I felt I was going out of my mind’. Caregiver 2, Page 16, Line 19, 20, 24, 25 ‘They even said to the children-‘You are dogs, coming here to beg for food.’ The children refused to ever go their house again. They have turned my children out of their rightful share in the land and ancestral house’. |

| xiv. | Anticipatory Grief | Caregiver 2, Page Line 1–3, 14–16 ‘I could not get up for two days from the shock. Kept crying. My eyes were swollen. Was in a very, very bad condition. Ever since I came to know, my whole life has been shattered. I keep thinking of how my whole life would be spent. What will my children do? How will they live? Who will take care of them?’ Caregiver 5, Page 18, Line 20-25 If something happens to us, who will take care of her? We think of that. Worry a lot. My wife often sits and weeps. I too sit and cry over the fact that today, we are there but after us, who will take care? Caregiver 4, Page 27, Line 1–5 We are parents, we would never want that something should happen to our child but seeing his suffering… fumbling for words) seeing him…suffer so much, getting so many injections, taking so many medicines, needles pricks for tests… having seizures through-out the day, he is in such agony, it would be better if he were freed of all this pain (in tears). One keeps wondering how much he is suffering. It is better the child should be free of all this suffering… because really, you can’t see your child like that’. |

| xv. | Support from the organisation | Caregiver 2, Page 12, Line 21–28, 36–41. ‘The attendant from the unit called up my in-laws and asked them-‘Is it only her responsibility to look after him? Can none of you come and stay with him in the hospital? The attendant’s wife would often call me and ask, ‘How are things, sister? How are you? Don’t worry. Be brave.’ Three-four times, she came to visit me in the hospital. She stayed with me. He had a friend in the Air force-his wife came to visit and stayed with me to help. She would make my husband’s favourite dishes, whatever he would ask for-and bring it to the hospital. Whatever financial help was required, that too, they gave. His own family did nothing to help’. Caregiver 6, Page 7, Line 2–20; Page 8, Line 7, 19–20; Page 9, Line 30, 31. Page 10 Line 1–6 ‘I feel better after coming to the campus… I got so much relief. Whenever there is any problem, I get prompt care. I sleep and eat properly. Earlier, I could not sleep at night. Earlier, I was not able to share all that was in my heart. Who could I tell? It was very difficult for me to stay in the village. My girls had to walk to school in another village. Now that I have been given a quarter inside the campus, my children are studying here. I am getting reimbursement of tuition fees. All the ladies help me. Someone brought books for my children. I really like it here. Now I want that my son should complete his education, I’ll fill his form and get him enrolled because I think this organisation is a good one’. |

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, The page and line numbers refer to the interview transcripts of the caregivers and are mentioned here for greater validity, reliability and transparency

Physical and emotional burden

Ten participants reported that caregiving tasks – lifting, toileting, bathing, laundry, cooking, and shopping, combined with a lack of rest and sleep led to physical exhaustion. Four caregivers had more than one patient in the family, multiplying the load. Inadequate information combined with caregiving tasks left women bewildered and overwhelmed, leading to chronic stress, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, worry, and sadness, affecting their health and worsened by having to handle things alone [Table 3] [Item ii and iii]. The interviews also highlight the familial and societal indifference and insensitivity toward women’s emotional needs [Table 3] [Item iv and v]. Mothers are often blamed for their children’s illness. Carer 4 gives a touching account of being made to feel responsible for her child’s condition, her husband’s indifference to a subsequent miscarriage, and the resulting anger, loneliness, and bitterness she felt [Table 3] [Item vi].

Expectation to be caregivers irrespective of their ability

Three participants in this study were pregnant; three sexagenarians had arthritis, diabetes, or hypertension and reported significant detrimental effects on physical and psychosocial well-being [Table 3] [Item ii,iii, iv]. An elderly lady, operated on for disc prolapse, persisted in lifting her husband even when helpers were present, risking a recurrence. Three young daughters who were students, looked after the household at the cost of their studies. Sons, brothers, and male relatives neither helped nor were expected to assist with household work. The pregnant caregivers had to carry on with lifting and nursing tasks in the absence of family who could help.

A scoping review of the effect of gender on caregiving in end-of-life care examined 15 studies (assessed with AMSTAR checklist and NICE guidelines; evidence level- strong-2, moderate-5, weak-8). It found a greater incidence of mental strain and significantly more depression in women.[16] A Canadian study of 283 subjects examining gender differences in spousal caregiving found women more likely to have comorbidities, anxiety, stress, and adverse health outcomes.[17] Wives were more vulnerable than husbands regarding both burden and self-esteem. Women caring for spouses, especially older women with unaddressed chronic conditions have significantly higher levels of strain. About 23.9% of women above 65 years reported chronic pain compared to 16.7% of men.[1]

Types of care provided also differ according to role perception. Wives see themselves as nurturers, provide more intensive care involving heavier lifting, rely less on formal care services, and suffer higher physical and emotional burdens, whereas husbands play managerial roles,[2,17] provide more informational support, and use community and homecare services more often.[18]

Gender stereotypes naturalize the ‘moral obligation’ of women to be caregivers – dismissed as ‘just doing their duty.’[5] They are believed to possess ‘greater emotional resilience which confers a natural ability to look after others’ so that even ‘tired or weak’ older women are expected to provide care, regardless of ability/needs.[1] Women internalize and self-impose these stereotypes, accepting their role and duty even when facing significant burdens, feeling incapable, and experiencing role conflicts when asking for or receiving help.[5] Men repress while women somatise negative emotions related to caregiving to make them acceptable. Gender norms require women to put others before themselves, promoting an ‘adherence to duty’ at the cost of their health and time.[1] Concepts of femininity lead to subordination to others’ views, the pursuit of perfection, low self-esteem, and guilt of feeling inadequate.[6] Women violating these expectations face criticism and sanctions.[19]

Notably, men performing hands-on caregiving are seen as doing something extraordinary and receive more appreciation and support. Campbell calls this the ‘Mr Wonderful’ attitude and exhorts that ‘esteeming men, while not extending such praise to women, reinforces gendered norms, devaluing women’s work.’[5] Demystifying and valuing caregiving irrespective of sex is important so that everyone can comfortably share experiences and ask for help, thus ameliorating the burden.[5] In the West, policy decisions have shifted the burden onto informal caregivers, presupposing the families’, especially women’s, ability to care, allegedly at the hidden cost of older women’s health.[1]

They need to manage everything alone [Table 3][item vii]. Traveling alone to the hospital was reportedly difficult due to long distances, lack of transportation, physical difficulty of transferring, and cultural issues which prevent travelling without chaperones [Table 3][Item viii]. Only one-third of Indian women are allowed to travel alone to a health facility.[20] Significantly, the freedom of movement is measured as ‘allowed to go alone,’ in terms of ‘being permitted’, not the ability to decide for themselves. Lack of education (Only 34% of rural Indian women receive 10 or more years of schooling[21]), awareness, and confidence – all contribute. Wives staying alone are, therefore, unable to access care regularly, causing delayed diagnosis and disrupted treatment/care.

Loss of social life

Ten caregivers reported an inability to socialize, resulting in loneliness and sadness [Table 3] [item ix]. Meeting friends relatives, and attending social functions is culturally difficult without spouses. Earlier studies about military families also highlight the difficulties wives have in building and accessing social support systems in the absence of husbands.[22,23]

Financial burden

Two participants had stopped working [Table 3] [Item x], and one was considering resignation due to difficulty in caring and working simultaneously. When caregivers are required to stay at home, it is the women who are automatically expected to give up employment, not the males. ILO also reports that Indian women bear a disproportionate burden of unpaid domestic and care work, hindering their ability to access gainful employment.[7]

More women than men are likely to carry out time-consuming, burdensome household tasks besides putting in more hours for caregiving, performing more intimate tasks, getting less support, and having to change their employment status more often and feel significantly more burdened.[18] Qualitative research suggests that younger adults with families find dealing with competing demands especially tough, leading to guilt, which further compounds the burden.[17,18] Younger women, especially, tend to perceive caregiving more negatively with greater distress. Higher levels of employment loss and emotion-oriented coping are significantly related to higher burden in women.[18] They are more sensitive to interpersonal issues, perceiving a lack of emotional mutuality or reciprocity as an indicator of their own deficiencies, which increases feelings of isolation and social inadequacy, contributing to poorer quality of life.[18]

Stigmatisation

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cancer, and intellectual disability still face stigmatisation in rural India. People believe cancer to be contagious and avoid visiting or even talking to patients and families, leaving caregivers without support. The legal and financial benefits for heirs can become a major bone of contention [Table 3] [Item xi]. Indian widows continue to be among the most vulnerable communities through the ‘triple burden’ of stigmatisation [Table 3] [Item xii], severely constrained resources, and sexual vulnerability.[23,24] Wives of HIV patients bear the brunt of ostracization, even though most Indian women get infected from spouses.[24,25] Both widows in the study reported ill-treatment by in-laws [Table 3] [Item xiii] – one even contemplated suicide. Often, the wives, especially HIV widows, are denied their share in the property.[24-28] Anticipatory grief was evident in nine interviews [Table 3] [Item xiv]. Neither family support nor professional counselling was available for these participants. An earlier study of veterans’ families shows higher levels of anticipatory grief in members who had dependent relationships, lesser education, and less social support[15] – all factors present in this group. However, the organisational support through free Medicare, attendants for admitted patients, daily provisions, bereavement support, and for widows – campus accommodation, children’s education, and compassionate jobs was much appreciated [Table 3, Item xv]. All the participants found the medical, social, and emotional support very helpful.

Verma, in his paper about stress in paramilitary forces, highlights wives having to bear the entire family burden alone.[29] Another article about psychosocial problems among military wives reiterates that stress in the soldier’s wife occurs due to new roles of helping family members cope during his deployment and deprivation of support.[23]

Utilisation of support services also varies.[17] Women use more transportation services, while men use more symptom management consultants. Services women found helpful include:[6,17]

Respite care with extended, flexible hours

Skill improvement training

Information support, counselling, medical/legal assistance

Health/social care navigation guidance

Education about accessing and utilising gender-sensitive psychological resources.[30]

Strengths

This is the first study related to gender roles affecting palliative caregivers in India, especially in service families.

Limitations

Drawn from only armed forces, the sample may not fully represent other groups.

CONCLUSION

Gender norms increase the burden for women caregivers especially soldier’s wives who have to manage alone in the male-dominated Indian society. There is an urgent need for identifying, questioning, challenging, and addressing stereotyped expectations and disparities in healthcare systems, practises, care goals and policies by sensitising staff, educating families, initiating care discussions, and undertaking more gender-related research.

Ethical approval

The research/study is approved by, Institutional Ethical Committee at Composite Hospital, BSF, Jalandhar. Ref No PA/CH Jal Ord /IEC/2016/355-56. Dated 15-03-2016.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was done for a dissertation for an MSc at Cardiff University. The First author received a Commonwealth Scholarship for the MSc.

References

- 'Because It's the Wife Who has to Look after the Man': A Descriptive Qualitative Study of Older Women and the Intersection of Gender and the Provision of Family Caregiving at the End of Life. Palliat Med. 2017;31:223-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becoming an Older Caregiver: A Study of Gender Differences in Family Caregiving at the End of Life. Palliat Support Care. 2022;20:38-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/genomics/gender/en/biological/differences [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Bethesda MD: NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) Available from: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender and Family Caregiving at the End-of-life in the Context of Old Age: A Systematic Review. Palliat Med. 2016;30:616-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender and Observed Complexity in Palliative Home Care: A Prospective Multicentre Study Using the HexCom Model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12307.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organisation Report: Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Pub World Economic Forum. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2022 [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Government of India. Available from: http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/report_tus_2019_0.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Report of OECD Database Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Database. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/521919/time-spent-housework-countries [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 22]

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants. 2006. Vulnerable Research Population. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Medical Research; :10-1. Available from: http://www.thsti.res.in/pdf/icmr_ethical_guidelines2017.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender Differences in Caregiving at End of Life: Implications for Hospice Teams. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:1048-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Communication with Relatives and Collusion in Palliative Care: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:2-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Women's Autonomy in Decision Making for Health Care in South Asia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2009;21:137-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk Factors for Anticipatory Grief in Family Members of Terminally Ill Veterans Receiving Palliative Care Services. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2015;11:244-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender Disparities in End of Life Care: A Scoping Review. J Palliat Care. 2023;38:78-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender Differences among Canadian Spousal Caregivers at the End of Life. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17:159-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender Differences in Caregiver Burden and Its Determinants in Family Members of Terminally Ill Cancer Patients. Psychooncology. 2016;25:808-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What Women Should Be, Shouldn't Be, are Allowed to Be, and Don't Have to Be: The Contents of Prescriptive Gender Stereotypes. Psychol Women Q. 2002;26:269-81.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/nfhs-4reports/india.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_nfhs-5.shtml [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- The Military Family Syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135:1040-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Woes of Waiting Wives: Psychosocial Battle at Homefront. Med J Armed Forces India. 2011;67:58-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender Inequality and the Spread of HIV-AIDS in India. Int J Soc Econ. 2011;38:557-72.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- India: HIV and AIDS-related Discrimination. 2001. Stigmatization and Denial. Available from: https://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub02/jc587-india_en.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Women, Property Rights and HIV in India. 2006. Exchange 3. :9-10. Available from: http://www.bibalex.org/search4dev/files/292431/122954.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Debt, Shame, and Survival: Becoming and Living As Widows in Rural Kerala, India. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2012;12:28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contemporary Social Position of Widowhood among Rural and Urban Area Special Reference to Dindigul district. Int J Adv Res Technol. 2013;2:69-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- An Analysis of Paramilitary Referrals to Psychiatric Services at a Tertiary Care Center. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:54-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caregivers' Morbidity in Palliative Care Unit: Predicting by Gender, Age, Burden and Self-esteem. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1465-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]