Brassiere-Wearing Practices and Issues among Post-mastectomy Women: A Systematic Review

*Corresponding author: Sukhpal Kaur, National Institute of Nursing Education, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. sukhpal.trehan@yahoo.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Saini R, Kaur M, Kumar A, Kaur S. Brassiere-Wearing Practices and Issues among Post-mastectomy Women: A Systematic Review. Indian J Palliat Care. 2024;30:315-21. doi: 10.25259/IJPC_192_2024

Abstract

This systematic review was carried out to appraise the evidence regarding the brassiere-wearing practices and problems faced by breast cancer survivors. An electronic search was carried out across eight databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Embase, CINAHL and ProQuest. Two researchers independently screened the studies for their eligibility and study quality. A total of 309 studies were assessed for eligibility. After conflict resolution by the third reviewer, five studies were selected for systematic review. All study outcomes in terms of the pattern of brassieres/prostheses, issues and challenges faced by women post-mastectomy were reviewed. It was observed that very few studies were published from various countries all over the world. All the studies were of descriptive type except one, which adopted a prospective randomised crossover design. The brassieres or prostheses, the survivors preferred were homemade made of cotton, cloth, wool, rice, sponge or commercially silicon-made. Weight of the brassiere/prostheses, discomfort, displacement while doing activities of daily living and impaired body image were common issues identified, while the unavailability of size or fit of the brassieres or requirement of alteration in clothes to meet clothing styles were common challenges faced by post-mastectomy women. It was concluded that the post- mastectomy used varied types of brassieres or prostheses with various associated issues and challenges.

Keywords

Breast cancer

Brassiere

Clothing issues and problems

Practices

Prostheses

INTRODUCTION

In India, breast cancer is now considered the most common cancer in urban and second most common in rural areas.[1] A higher proportion of the disease in India is occurring at a younger age than the Western countries.[2] Furthermore, a woman’s breast is frequently regarded as a symbol of her identity. It stands for her motherhood, attractiveness, femininity and sexuality. The most common surgical treatments for the disease are mastectomy and lumpectomy.[3] Many surgical and radiation-related physical changes to the breast and torso may include surgical scars, swelling, sensitive skin and alteration in the size and shape of the breast.[4] Moreover, a mastectomy can have a negative emotional, physical and social impact on the women. These negative consequences may include disturbed body image, low self-esteem, diminished self-confidence, diminished femininity and altered interpersonal and societal interactions.[2] To overcome these changes, many survivors require suitable fabric and design of brassiere. The difficulty in getting a well-fitting brassiere can cause both physical and psychological distress, impeding a patient’s sense of normalcy and well-being after cancer.[5] The brassiere is intricately linked to a woman’s body image. Following mastectomy without reconstructive surgery, the women may have two options: either they can go flat or can utilise an external breast prosthesis, such as a full silicone breast or additional bra padding.[6] Patients who elect to go flat have special needs since mastectomy can leave the breast wall concave and excess skin or fat tissue that impairs their body image. These patients might use a camisole or sports brassiere to even out the chest. The women’s shirt is designed in such a way that there is an extra space for the breasts. Thus, the patients undergoing mastectomy had to face this problem when their breasts did not fit well in their dresses, giving them a feeling of poor body image. External breast prostheses require a special kind of brassiere with pockets for the prostheses to fit into it. The prosthetic’s fit is important to women’s satisfaction with their appearance.[7]

It is vital to consider how cultural factors also impact the choices and experiences of a selection of the brasseries. Intercultural differences exist in values, expectations, attitudes, language, surroundings and individual perceptions regarding the disease and treatment understanding. Some patients opt not to wear brassieres after having reconstruction because they do not feel that they need the support or they find wearing brassieres to be too unpleasant. Others choose soft, wireless brassieres like sports brassieres while some have to customise their brassieres. The style and design of the brassiere are influenced by factors such as breast asymmetry, scar location, limited arm movement and skin sensitivity.[6] Following the breast surgery, some of the patients may also experience increased swelling, decreased blood flow, impaired sensation, drainage, pain, etc., necessitating the use of a compression wrap or post-surgical garment.[8] These necessitate the modification in the design and fabric of the brassiere.

This review aimed to systematically search and synthesise the evidence from quantitative studies regarding the brassiere-wearing practices and problems faced by breast cancer survivors; to understand their concerns, and thus to provide a theoretical basis for the researchers, and designers to develop appropriate brassieres for the survivors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was conducted using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with the registration number CRD42023384992.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The review included all the studies related to ‘brassiere practices, issues and problems faced by women who had undergone mastectomy due to breast cancer’. No restriction regarding the patient’s age, race, country, type of study or publication date was made. However, only the English language studies carried out using quantitative approaches were included in the review. All the studies unrelated to research questions, not available as full text or available only as abstracts and qualitative studies were excluded from the search.

Study design

The review included all experimental, quasi-experimental, randomised controlled trials, non-randomised controlled trials, observation, descriptive, prospective and retrospective cohort studies. All the unpublished theses were also considered.

Time frame

There was no restriction on the time frame for extracting studies.

Information sources

Eight electronic databases were searched systematically for the relevant studies to be included in the current systematic review. The databases were as follows: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Embase, CINAHL and ProQuest (grey literature) from their inception till 8th August 2023.

Search strategy

Appropriate Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were recognised and used for search. The following MeSH terms were used: ‘Practices, pattern, issues, problems, behaviour, clothing, undergarment, brassiere, breast cancer and post-mastectomy’. ‘External breast prostheses’ term was used for searching by other methods or by citations. A draft of the search strategy in various databases with the appropriate MeSH terms is depicted in Table 1.

| S. No. | Database | Search strategy | Number ofarticles retrieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | PubMed | (((pattern) OR (practice)) AND ((((bra*) OR (clothing)) OR (undergarment)))) AND (((‘post-mastectomy’ OR (‘breast cancer surgery’)) OR (‘breast cancer survivor’)) (((issue*) OR (problem*)) AND ((((bra*) OR (clothing)) OR (undergarment)))) AND (((‘post-mastectomy’ OR (‘breast cancer surgery’)) OR (‘breast cancer survivor’)) | 23 |

| 2. | Scopus | (pattern OR practice) AND ((bra*) OR (clothing) OR (undergarment)) AND ((‘post-mastectomy’) OR (‘breast cancer surgery’) OR (‘breast cancer survivor’)) (issue* OR problem*) AND ((bra*) OR (clothing) OR (undergarment)) AND ((‘post-mastectomy’) OR (‘breast cancer surgery’) OR (‘breast cancer survivor’)) | 17 |

| 3. | Embase | ‘pattern’ OR ‘practice’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ ‘issue*’ OR ‘problem*’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ | 19 |

| 4. | Web of Science | (Pattern OR practice) AND ((bra*) OR (clothing) OR (undergarment)) AND ((‘post-mastectomy’) OR (‘breast cancer surgery’) OR (‘breast cancer survivor’)) (issue* OR problem*) AND ((bra*) OR (clothing) OR (undergarment)) AND ((‘post-mastectomy’) OR (‘breast cancer surgery’) OR (‘breast cancer survivor’)) | 48 |

| 5. | Science direct | Pattern OR practice AND bra* OR clothing OR undergarment AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery OR ‘breast cancer survivor’issue* OR problem*AND bra* OR clothing OR undergarment AND ‘post-mastectomy’OR ‘breast cancer surgery OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ | 5 |

| 6. | CINAHL | ‘Pattern’ OR ‘practice’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ ‘issue*’ OR ‘problem*’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ | 153 |

| 7. | ProQuest (grey literature) | ‘Pattern’ OR ‘practice’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ ‘issue*’ OR ‘problem*’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ | 8 |

| 8. | Google Scholar | ‘Pattern’ OR ‘practice’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ ‘issue*’ OR ‘problem*’ AND ‘bra*’ OR ‘clothing’ OR ‘undergarment’ AND ‘post-mastectomy’ OR ‘breast cancer surgery’ OR ‘breast cancer survivor’ | 32 |

| 9. | Search by other methods or by citations | ‘External breast prostheses’ | 4 |

Selection of studies

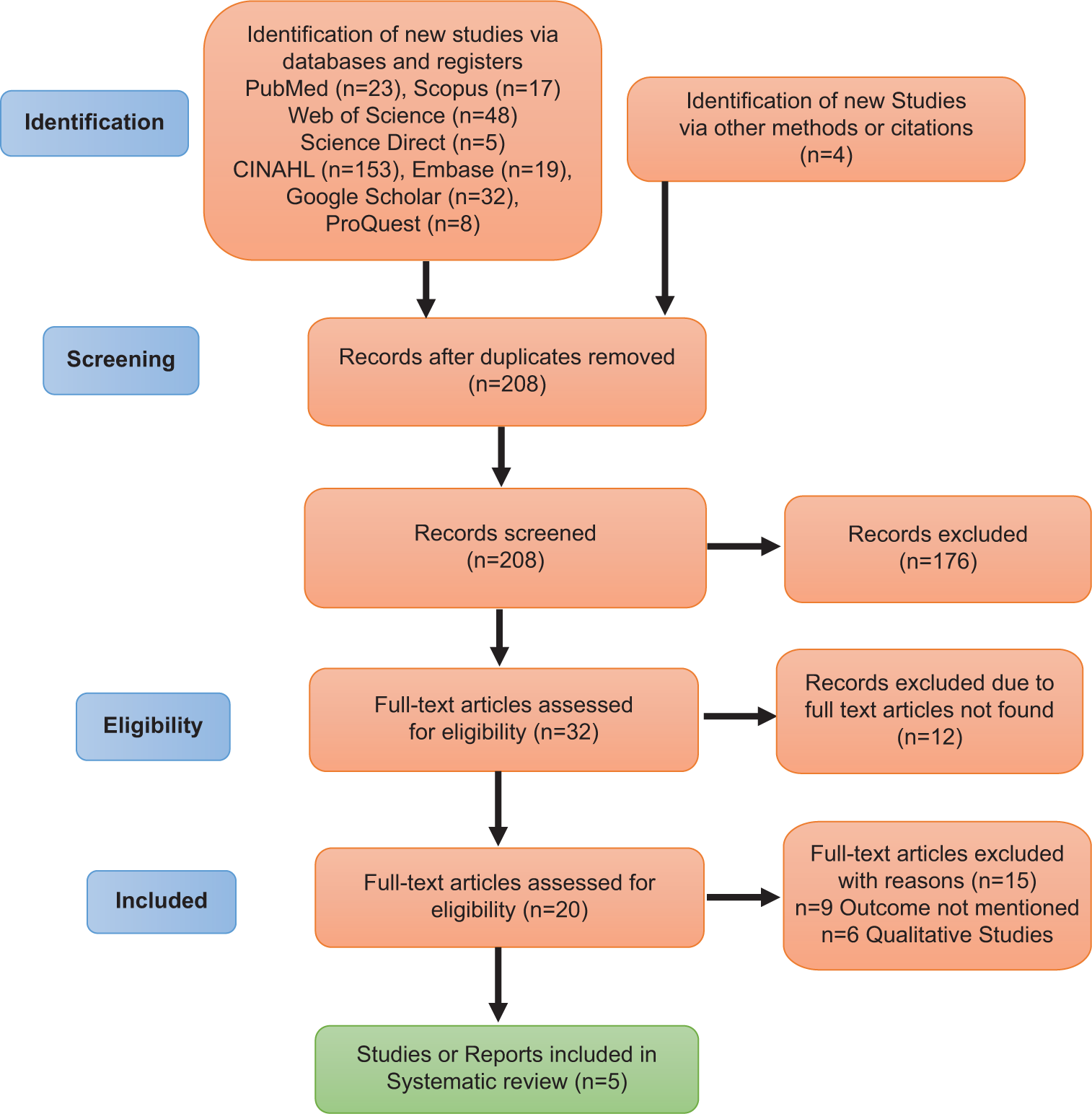

On the completion of the search, a total of 309 studies were assessed and uploaded into RAYYAN software. The studies were assessed for duplicacy and a total of 101 duplicate records were excluded from the study. The remaining 208 studies were screened independently by the two reviewers based on their titles and abstracts. After conflict resolution by the third reviewer, 32 studies were included in the study. Full text of the available studies was extracted. The investigators were able to retrieve the full text of 20 studies. The 20 studies were again screened independently by the two reviewers. Any conflict that evolved during the process of study selection was resolved through a dialogue with a third reviewer. After conflict resolution by the third reviewer, five studies were selected for systematic review. The results of the search are depicted in the PRISMA diagram [Figure 1].

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flowchart for systematic review.

RESULTS

Description of relevant studies

Five relevant studies meeting the eligibility criteria were selected. All the selected studies were in English language. It was observed that very few studies were published by scientists from various countries worldwide in the past 13 years. The available studies were from The Netherlands (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Michigan (n = 1), Brazil (n = 1) and India (n = 1). The distribution of studies varies over time as studies were conducted more frequently after 2009 (2009, n = 1; 2010, n = 2; 2014, n = 1 and 2015, n = 1) indicating the increased interest of scientists in exploring the pattern of external breast prostheses use by post-mastectomy women and the problems faced by them [Table 2].

| ID | Reference | Year | Country | Research methods | Sample | Data Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Thijs-Boer et al.[9] | 2001 | The Netherlands | Prospective Randomised Crossover | 101 women with one-sided mastectomy | Inspection and Questionnaire |

| 2. | Gallagher et al.[13] | 2009 | Ireland | National Survey | 527 women with mastectomy and requiring/wearing a breast prostheses, 32 Breast Care Nurses, 12 Retail Prostheses Fitters | Questionnaire |

| 3. | Beard[10] | 2011 | Michigan | Online survey | 87 women post-mastectomy | The Mastectomy Attitude Scale |

| 4. | Borghesan et al.[11] | 2014 | Brazil | Exploratory cross-sectional | 76 women with mastectomy using external breast prostheses | The questionnaire filled through telephonic survey |

| 5. | Ramu et al.[12] | 2015 | India | Descriptive longitudinal | 63 women with mastectomy | Telephonic interview 3 years after completion of therapy |

All the studies were of descriptive type (n = 4) except one from The Netherlands, which adopted a prospective randomised crossover design. Interviews (n = 2) and questionnaires (n = 3) were the adopted methods to collect data in all the studies. Most of the studies[9-12] had included women above 20 years who underwent mastectomy for the survey, except a study from Ireland[13], which also included women of 18 years. The mean age of women reported was between 50 and 60 years.

Pattern of external breast prostheses used by post-mastectomy women

Various types of brassieres and prostheses used by post-mastectomy were investigated (n = 3). A study from The Netherlands[9] reported two types of prostheses being used by different groups of women that are self-adhesive prostheses made of silicone gel covered with a layer of polyurethane which can be fixed into position using Velcro Strips and which do not require the use of a brassiere. It was preferred by 59.3% of women. The other was a traditional type of prosthesis, which was made up of cotton wool and fixed inside the brassiere and was preferred by 40.7% of women. It was further reported that the preference for this type of prosthesis was not related to age. The Ireland study[13] reported varied practices of brassiere and prostheses use among post-mastectomy women. The women used either a padded brassiere (26.4%) or a homemade prosthesis (8.2%) made of cotton wool, rice, shoulder pad or sponge and traditional silicon prostheses. However, the majority of post-mastectomy women from India reported the use of homemade cotton or cloth prostheses (77.8%) due to their unaffordability with silicone prostheses (22.2%).[12] Thus, the most popular material used for external breast prostheses was silicon, though homemade cotton or cloth prostheses were also equally prevalent among post-mastectomy women [Table 3].

| Factors | Study |

|---|---|

| Pattern of brassieres preferred by post-mastectomy women | |

| Home-made prostheses made of cloth, cotton wool, rice, shoulder pad or sponge, Padded Cups or bra, Silicon prostheses and soft fibre-filled prostheses | [9,12,13] |

| Issues with wearing brassieres by post-mastectomy women | |

| Perception of decreased body image | [11,12] |

| The feeling of discomfort with the brassiere | [12,13] |

| The feeling of the weight of a brassiere or prostheses | [9,11,13] |

| Concerns with the smell of brassiere or prostheses | [11] |

| Feeling body sensations of stitches, pain, pulling and dormancy at the place of surgery and phantom limb | [11] |

| Displacement of the prostheses while doing activities of daily living | [11,13] |

| Skin rashes under the strips of some self-fitting prostheses made of silicon | [9] |

| Local itch and irritation | [9] |

| Pain in shoulder and neck | [9] |

| Challenges faced by post-mastectomy women while making decisions about brassieres or prostheses | |

| Cost constraints | [12] |

| Unawareness about the presence of prostheses | [12] |

| Unavailability of size for fit | [9,12] |

| Activity limitations for swimming, sunbathing, sporting and sexual activity | [13] |

| The problem faced while buying clothes | [13] |

| Difficulty buying clothes to conceal scars | [10] |

| Requirement of alteration in clothing to meet clothing styles | [13] |

| Being socialised | [13] |

Issues related to brassieres or prostheses used by post-mastectomy women

Various concerns and issues related to wearing a variety of brassieres and external prostheses by post-mastectomy women were reported in studies from different countries [Table 3]. The weight of the brassiere or prostheses emerged as an important concern. It was reported as a major concern by 24% of women in an Ireland study.[13] They reported that the weight of the prostheses put pressure on the shoulder and neck and led to pain in the shoulder.[9,13] The studies from Ireland and Brazil reported displacement of prostheses (66.7% and 14.3%, respectively) either due to their weight or inappropriate fixation inside the brassiere while the women were engaged in doing activities of daily living.[11,13] The women from Ireland[13] and India[12] also felt discomfort (17.3% and 51.2%, respectively) with the use of prostheses. Few studies tried to explore the psychological issues with wearing external prostheses or brassieres, where body image concerns were more prevalent among post-mastectomy women. An Indian study by Ramu et al.[12] reported that the women using prostheses experienced body image problems (26%) as compared to the non-users. It was also reported that the younger women (100%) who underwent mastectomy were common users of prostheses as compared to older women above 60 years (23%).[12] A Brazilian study reported that post-mastectomy women using external breast prostheses were more satisfied (56.6%) with their use.[11] Feelings of body sensations of stitches, pains, pulling, dormancy and phantom limb were also reported in this study apart from concerns with the smell of brassiere or prostheses. Local issues with wearing the external breast prostheses, such as local itch, irritation, development of skin rashes under the strips of the brassiere and pain in the shoulder and neck due to the weight of the prostheses, were also identified.[9]

Challenges faced by post-mastectomy women

Challenges faced by post-mastectomy women while making decisions about brassieres or prostheses were also explored. The women from Ireland and India reported a great challenge in buying brassieres or prostheses due to their non-availability in size or inappropriate fit (27.6% and 41%, respectively).[12,13] Problems were also faced while buying clothes which can conceal scars or match with the previous fashion styling of the women,[10,13] and if available, need alteration to meet their clothing styles[10] were the challenges reported by post-mastectomy women. Unaffordability due to financial constraints (52%) was reported in developing countries like India, where women continued to wear homemade cotton or cloth prostheses. [12] The women also reported difficulty in performing various activities such as sunbathing, sports, sexual activity and socialising with friends and relatives [13] [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

Mastectomy significantly impacts women’s self-image due to the changes in the appearance of breasts following the procedure. It diminishes their feeling of femininity.[14] This leads to anxiety and anguish in the women to the extent that they avoid going to public places. Therefore, maintaining women’s health requires post-mastectomy rehabilitation to maintain their overall health and well-being.[15]

A breast prosthesis is an artificial breast form that restores the shape of the breast that has been surgically removed. The prostheses are generally made from materials that are like natural breasts. They are available in a variety of shapes and sizes.[16] The results of the various studies in the current systematic review revealed that after mastectomy, these patients usually wear self-adhesive and conventional (homemade) prostheses. An adhesive prosthesis has silicone that is attached to the woman’s skin and is suitable for a longer duration,[17] whereas a conventional prosthesis is worn inside the brassiere, which has a special pocket to hold the material (wool/cloth/fibre/rice) that can be moulded like the shape of the breast. Furthermore, homemade prostheses are usually soft, lightweight and comfortable. They can be worn right after the surgery, while silicone prostheses can be worn 6–8 weeks after surgery once the wound is well healed.[18] Irrespective of the kind of prostheses, its care is very important. The prosthetics should be cleaned daily in warm water and dried with a fresh towel to get rid of dirt and sweat. The silicone prostheses should be prevented from contact with sharp objects and, when not in use, should be kept inside the case/cover.[19] The present study also highlighted that the age of the patients strongly affects prosthesis use, and it was also reported that the younger women who underwent mastectomy were common users of prostheses as compared to older women. It may be that younger women are more concerned with their femininity and body image as they participate in social gatherings more often. In addition to the duration of brassiere wearing, most women prefer to wear a bra when going outside and during social gatherings.

The present systematic review elucidates a wide range of problems with the use of external prostheses and brassieres by post-mastectomy women. The common complaint was its weight. Prostheses weight puts strain on the neck and shoulder, causing shoulder pain. However, some women also complained about its displacement during activity. Kubon et al. [20] also reported that pain, discomfort and displacement of the prostheses were the common complaints.

The main goal of breast prostheses and brassieres is to help patients regain their natural body shape after mastectomy.[21] However, many of these cause discomfort. Our review showed that itching, skin rashes and pain were the common complaints reported by the patients. Mainly, natural prostheses cause less discomfort to the patients because they are to be worn inside the brassiere and do not touch the skin directly. Hence, there could be less chance for skin rashes and local itch to happen, but they can put pressure on the shoulder and cause shoulder pain.[16] On the other hand, an adhesive on a prosthesis can be uncomfortable due to sweating caused by the heat, which further causes skin rashes and itch. Consistent with the previous study,[22] it has been reported that breast prostheses can lead to skin rashes, which result in dissatisfaction with the prostheses among the survivors.

In the current review, various challenges related to using prostheses were also identified. These included unavailability of the size or inappropriate fit of brassieres or prostheses, problems faced while buying clothes, unaffordability and difficulty in performing various activities such as sunbathing, sports, sexual activity and socialising with friends and relatives. These findings correspond with the available literature.[7,23] Another challenge was the lack of information about the prostheses, as reported by Gallagher et al., which led to dissatisfaction.[13] A study from Korea has reported that only a few post-mastectomy women used prostheses due to a lack of awareness and their unaffordability for silicon prostheses.[24] It is important to note that due to the lack of a general health insurance system, most of the patients have to pay from their pocket for the required health services. Furthermore, the participants reported that the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer had already put a heavy financial burden on their families, so the usage of prostheses was perceived as a cosmetic expenditure only. Therefore, most of the women tried to find an alternative, which is how they compromised the quality of the prostheses. Some had stitched their prostheses on their own using cotton or foam, etc., the readily available material. Unfortunately, many patients are not aware of its availability or sales and do not feel comfortable asking their doctor/nurses about the prostheses. In addition, the Indian market for mastectomy brassieres is notably neglected, with available imported products often not fulfilling the Indian body type.[25] Participants in various studies of the current review also highlighted the issues related to fit, materials and design. They had difficulty in finding the appropriate size and design of the prostheses. After the surgery, these patients have common problems such as an imbalance of body structure, shoulder slumping and difficulty in using the back opening brasserie due to the pain in the underarms and back. Thus, keeping the above in mind the brassieres or prostheses have been designed to aid the patients to lead a relatively better and pain-free life. In addition, the prosthetic brassieres are available only in one pattern with limited/no options in colour, fabric and pattern. This also impacts the patients psychologically.[26] Variations in the fabric have been tried to boost the morale of the patients. Roberts et al.[27] identified the quality of the prostheses as one of the most important aspects considered when selecting breast prostheses.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This rigorous systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines. Two independent authors reviewed each stage of the process. In case of any disagreement, all three authors met to reach a consensus. The major limitation was a lack of eligible studies. Also, due to the scarcity of appropriate data, we could not perform meta-analysis.

Recommendations

This not much-explored issue related to clothing and grooming practices of breast cancer survivors needs a lot of various kinds of research studies to be conducted including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method research designs to create more and more shreds of evidence. Apart from this, similar kinds of studies should also be carried out on the women with disability (WWD) as they might be having their own health problems, concerns, and related issues.[28] This will help in planning future strategies for the survivors to provide them with quality care in order to enhance the self-esteem of the survivors.

CONCLUSION

The current review has explored various types of brassieres and prostheses used by survivors of breast cancer post-mastectomy and has also highlighted various challenges faced by them while making decisions about these.

This will help in planning future strategies for the survivors to provide them with quality care to enhance the self-esteem of the survivors. There is a need for the involvement of more and more companies, designers and other stakeholders to customise and design appropriate size brassieres, taking into consideration body type, needs, weight and fabric, which could be available to post-mastectomy women at affordable prices.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in Indian women. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:289-95.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Breast Cancer in India: Present Scenario and the Challenges Ahead. World J Clin Oncol. 2022;13:209-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Breast-shape Changes During Radiation Therapy after Breast-conserving Surgery. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2018;6:71-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Undergarment Needs after Breast Cancer Surgery: A Key Survivorship Consideration. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3481-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Breast Cancer Survivors' Wearable Product Needs and Wants: A Challenge to Designers. Int J Fashion Design Technol Educ. 2017;10:308-19.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- External Breast Prostheses in Post-mastectomy Care: Women's Qualitative Accounts. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19:61-71.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bust Prominence Related to Bra Fit Problems. Int J Consum Stud. 2011;35:695-701.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Conventional or Adhesive External Breast Prosthesis? A Prospective Study of the Patients' Preference after Mastectomy. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:227-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Contemporary Clothing Issues of Women who were Post-mastectomy [Dissertation] Michigan: Western Michigan University; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variables that Affect the Satisfaction of Brazilian Women with External Breast Prostheses after Mastectomy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:9631-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pattern of External Breast Prosthesis Use by Post Mastectomy Breast Cancer Patients in India: Descriptive Study from Tertiary Care Centre. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2015;6:374-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experiences in the Provision, Fitting and Supply of External Breast Prostheses: Findings from a National Survey. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2009;18:556-68.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Body Image of Women with Breast Cancer after Mastectomy: A Qualitative Research. J Breast Health. 2016;12:145-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Resilience as a Protective Factor for the Body Image in Post-Mastectomy Women with Breast Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1181.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Epicutaneous Breast Forms. A New System Promises to Improve Body Image after Mastectomy. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:295-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Presenting All the Choices: Teaching Women about Breast Prosthetics. Medscape Womens Health. 2001;6:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comments on the Usage of External Breast Prosthesis by Indian Women Undergoing Mastectomy. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2022;13:516-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Women Experiences of Using External Breast Prosthesis after Mastectomy. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017;4:250-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A Mixed-methods Cohort Study to Determine Perceived Patient Benefit in Providing Custom Breast Prostheses. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:e43-52.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based Recommendations for Building Better Bras for Women Treated for Breast Cancer. Ergonomics. 2014;57:774-86.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term Role of External Breast Prostheses after Total Mastectomy. Breast J. 2009;15:385-93.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives of Women about External Breast Prostheses. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2012;22:162-74.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experiences of the Use of External Breast Prosthesis among Breast Cancer Survivors in Korea. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2012;18:49-61.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development of Mastectomy Bra for Breast Cancer Survivors. In Ergonomics for Design and Innovation. Humanizing Work and Work Environment: Proceedings of HWWE 2022:151-62.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design and Development of Prosthetic Brassieres for Breast Cancer Patients. J Sci Res. 2021;65:157-64.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- External Breast Prosthesis Use: Experiences and Views of Women with Breast Cancer, Breast Care Nurses, and Prosthesis Fitters. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:179-86.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An Integrated Qualitative and Quantitative Study on Sexual and Reproductive Health Problems Faced by Women with Disabilities in Chandigarh, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;163:818-24.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]