Translate this page into:

A Narrative Literature Review on Human Resource Planning for Palliative Care Personnel

Address for correspondence: Dr. Majid Taghavi, Sobey School of Business, Saint Mary's University, 923 Robie Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3C3, Canada. E-mail: majid.taghavi@smu.ca

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A literature search was started with the objective of finding works pertaining to the use of operations research techniques in planning for human resources in palliative care. Since the search indicated that there is no such work, in this paper, we report on the literature on workforce planning and human resource planning for palliative care personnel. Using our findings, we discuss the factors that influence the supply and demand for the palliative care workforce. Our results show that the enhancement of efficiency, training more primary caregivers to deliver palliative care, and allowing for mid-career specialist training are practical ways to compensate for the gap between the supply and demand in the palliative care workforce.

Keywords

Demand

health workforce planning

palliative care

primary care

supply

INTRODUCTION

In May 2014, the province of Nova Scotia released an Integrated Palliative Care Strategy (https://novascotia.ca/dhw/palliativecare/documents/Pallative-Care-Progress-Report.pdf) with the vision that “all Nova Scotians can access integrated, culturally competent, quality palliative care in a setting of their choice” (https://novascotia.ca/dhw/palliativecare/documents/Integrated-Palliative-Care-Strategy.pdf). This strategy recognizes that due to Nova Scotia's aging population, the need for end-of-life-care is expected to grow over the next 20 years. In addition to the increase in patient population, the role of palliative care is evolving. It used to be that palliative care was considered mainly for persons dying of cancer and very close to the end of life, but increasingly, palliative care is being advised for persons with organ failure (e.g., congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and frailty (e.g., dementia) earlier in the trajectory of their illness.[1] Due to these changes, it is expected that there will be an increased need for specialist palliative care professionals in Nova Scotia.

The Nova Scotia Health Authority was interested to plan for the number of specialist palliative care personnel needed over the next 20 years given the anticipated demand growth. A mathematical programming framework using operations research techniques was proposed to inform the decision. As the first step, we have done a survey of the literature to find previous works that used operations research techniques for palliative care human resource planning. It turns out that there is no such work in the existing literature.

The objective of this article is to explore the existing English-language literature in human resource planning for palliative care and to find the factors that influence the supply and demand of palliative care personnel. We aim to assess and synthesize the type and rigor of the various human resource planning research and methods identified in the published peer-reviewed literature that explore how many specialist palliative care personnel are required to meet palliative care needs. Rather than conducting a full systematic literature review, our goal was to develop a framework for palliative care workforce planning that can serve as a primary base for more exploration into the subject matter.

METHODS

In order to assess the existing literature, a narrative synthesis was conducted.[2] A systematic search of MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library was conducted. A list of search phrases was developed by the research team which included “end of life,” “life limiting illness,” “palliative,” “hospice,” “terminal,” “human resources,” “staffing,” and “workforce,” These terms were used to identify appropriate controlled vocabulary phrases in the databases where controlled vocabularies are used. Each of the databases was searched individually using keywords, and all the identified controlled vocabulary phrases from all sources as plain text phrases and appropriate controlled vocabulary phrases for the database were searched as such. Using these search terms, a total of 1044 potentially relevant articles were returned from the relevant databases. Four additional articles were later identified and added to the study through manual searches.

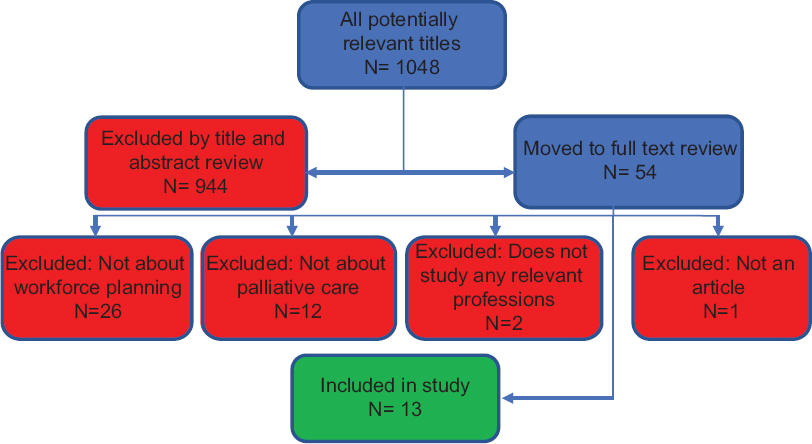

With the criteria that relevant material must pertain to (1) human resource planning, (2) palliative care, and (3) physicians, nurses, or social work professionals, the articles were assessed for relevancy by two of the authors (MT, ER) using the Covidence (www.covidence.org) application. Titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed by MT and ER independently. Any conflicts were resolved through discussion and consensus. The full text of articles not excluded by title and abstract alone were independently reviewed by MT and ER again, and any conflicts were again resolved through discussion and consensus. Once completed, this process yielded 13 relevant articles. This literature search process is outlined in Figure 1.

- Process to identify the relevant literature

RESULTS

Of the 13 relevant articles identified [Table 1], all are in agreement that there is an existing shortage of hospice and palliative care professionals and that without concerted planning and intervention that shortage will only become worse. While all the literature included here pertain to the human resource planning of hospice and palliative care physicians, nurses, and/or social workers, there are limitations to the robustness of these few pieces identified. While published in academic journals, five of the 13 pieces were opinion pieces or letters to the editor, not full peer-reviewed articles.[34567] Although two of these letters to the editor were brief outlines of informal and semi-formal quantitative studies in which the authors explored existing staffing levels in palliative care programs, the degree to which respondents found their staffing levels to be satisfactory.[36]

| Study | Country | Professions |

|---|---|---|

| Salsberg 2002 | The USA | Physicians |

| Goodman et al. 2006 | The USA | Physicians |

| Chiarella and Duffield 2007 | The USA, Germany, the UK, Australia | Nurses and other unspecified |

| Billings 2008 | The USA | Physicians and nurse practitioners |

| Ogle 2009 | The USA | Social workers, physician’s assistants, Chaplains, nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians |

| Lupu 2010 | The USA | Physicians |

| Roberts and Hurst 2013 | The UK | Nurses |

| Douglas 2012 | The USA | Nurses |

| Quill and Abernethy 2013 | The USA | Physicians |

| Kamal, Maguire, and Meier 2015 | The USA | Physicians |

| Spetz et al. 2016 | The USA | Social workers, physician’s assistants, Chaplains, nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians, osteopaths |

| O’Mahony et al. 2018 | The USA | Chaplains, social workers, nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians |

| Dudley, Chapman, and Spetz 2018 | The USA | Physicians, Social workers, Chaplains, nurse practitioners, nurses |

Of the remaining eight studies, only two provide any estimates or tools with which to predict the future numbers of and the potential need for palliative care professionals. Roberts and Hurst[8] adapt an existing framework used in other specialities to assess the staffing of nurses in hospices and palliative care wards.

They consider five factors in their assessment: (i) bed occupancy and the degree to which patients are dependent on the nurses' care, (ii) the types of activities the nurses are performing, (iii) the quality of care, (iv) vacation and sick leave, and (v) full-time equivalent (FTE) by experience and education of the clinician. While this study does not provide an estimate of the need for clinicians on the basis of geographic population, the authors provide a “staffing multiplier” based on their findings, which is intended for use by facility administrators to calculate the required FTE of nurses based on the number of beds in the facility.

The only study to provide a population-based estimate of the need for hospice and palliative care clinicians is the report prepared by Lupu 2010[9] for the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. The study identifies programs which are considered to be exemplary in their physician staffing models and extrapolate what it would take to provide similar staffing across the United States. The demand for these physicians was based on the use of hospice and palliative care services, population, and the FTE of physicians, not individuals. The existing and required supply of physicians was calculated using membership and certification lists from the appropriate organizations.

Once the demand for physicians was calculated in FTEs, the authors considered data estimating the percentage of their work hours spent providing hospice and palliative care directly to patients. Many qualified physicians spend only part of their time on hospice and palliative medicine while also working in other specialties. The study found that there was a gap of between 2787 and 7510 FTE physicians between the existing and desired supply. The authors show that this could translate into the need for between 6806 and 24,500 trained physicians. While this estimate is one the only to quantify the supply and demand of hospice and palliative care clinicians, the author acknowledges the limitation that the model has many variables and provides only a picture of a single time and location. It does not take into account population growth, aging populations, or the increasing demand for hospice and palliative care, thus cannot be used to predict the future need.

DISCUSSION

According to our study of the relevant articles published with respect to palliative care staff planning, factors that impact the number of palliative care professionals can be broken into supply factors and demand factors:

Factors influencing the supply of hospice and palliative care professionals

One of the most prevalent themes among the literature is the lack of appropriate training opportunities for professionals who desire to work in hospice and palliative care. This is not due to a lack of fellowship opportunities for the United States physicians.[5] Rather, it seems palliative medicine is often a field in which physicians develop an interest later in their careers. The literature suggests that a mid-career training program for hospice and palliative care would be a good solution to increase the number of accredited, trained physicians.[7910]

Among nurses, there are also limited training opportunities to work in hospice and palliative care and much of the existing training comes on the job either formally or informally.[11] Whether the relationship is cause or effect we do not know, it is believed that the lack of training opportunities has an effect on the reported high rates of turnover in hospice and palliative care professionals.[12] In a high-stress field such as hospice and palliative care, not having the right skills to cope can make the difference in whether a professional continues on in the job.[412] Further backing up this theory, Roberts and Hurst found a statistically significant difference in the sick and vacation time taken by hospice and palliative care nurses than by nurses in other fields.[8]

The literature pertaining to human resource planning for physicians makes the importance of recognizing that many hospice and palliative care physicians work only part time in that specialty. Those planning for hospice and palliative care staffing must ensure that enough individuals are properly trained to provide services on a part-time basis.[8111314]

Factors influencing the demand for hospice and palliative care professionals

The relatively recent development of the hospice and palliative care as a specialty is often cited as a contributing factor in the difficulties of staffing for hospice and palliative care professionals.[579101315] In the time since hospice and palliative care became a recognized and accredited specialty, the field itself has rapidly changed. While originally conceived of as a service only for those very near the end of life, as the specialty grows, hospice and palliative care professionals are being asked to become involved in care at earlier stages to control pain and manage symptoms.[6811131415]

Unlike areas of medicine that have a long history and more clearly defined scope, hospice and palliative care is practiced differently in different regions, settings, and among different teams. The makeup of an interprofessional palliative care team is rarely the same in different programs.[47101314] For this reason, staffing is difficult to plan for as with each different funding structure or manager, team makeups change and as the teams change, so does their efficiency.[457911121415]

There is also variation in hospice and palliative care in the settings in which care takes place. Residential hospice, community hospice, hospital inpatient, hospital consult are among the different ways in which hospice and palliative care is provided. The variation in setting, program structure, and staffing structure means there is also a great deal of variation in the number of patients, a team can see per FTE.[457911121415] In addition to the variation in structures, the experience level of the professionals on the team has been shown to make a difference in the efficiency of the team.[49] This brings further significance to the high rates of turnover.

CONCLUSIONS

While there is not much literature on the subject of human resource planning for hospice and palliative care, the literature agrees there is an existing shortage of as well as a growing need for qualified professionals. It is important that those in charge of planning for end-of-life care recognize that the widening scope of palliative care and the aging population offer no letup in the gap between the supply and demand for hospice and palliative care.

While the existing literature is generally in agreement, there are gaps in the knowledge base. Due to the varied nature of hospice and palliative care, it is difficult to get a comprehensive picture of the landscape. The literature is mainly focused in the United States and while some of the general principles apply to Canada, the differences between the two systems are many.

There remain no population-based predictions on the need for hospice and palliative care professionals. Although some of the literature touches on social workers as a part of the interdisciplinary team, there is little information on the specific challenges faced by social workers in terms of professional education and culture, whereas there are several studies that each focus on specifically nurses and physicians.

The literature provides several recommendations for the best way to reduce the gap between the supply and demand of palliative care professionals. Those that make recommendation for a solution seem to fall within three general categories:

-

Train more primary caregivers and those in other specialties to perform basic hospice and palliative care[579121415]

While further information is gathered and hospice and palliative care continues to evolve, it is important that we remain aware of the staffing issues and plan accordingly.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation for supporting this study. Also, the authors appreciate the comments made by Dr. Grace Johnston.

REFERENCES

- Integrating cancer care beyond the hospital and across the cancer pathway: A patient-centred approach. Healthcare Q. 2015;17:28-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conceptual recommendations for selecting the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to answer research questions related to complex evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:43-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physician-nurse staffing on palliative care consultation services. J Palliative Med. 2008;11:819-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Staffing for end of life: Challenges and opportunities. Nursing Economics. 2012;20:167-9, 178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolving the palliative care workforce to provide responsive, serious illness care. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:637-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Staffing of palliative care consultation services in community hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:509-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Generalist plus specialist palliative care — creating a more sustainable model. New England J Med. 2013;368:1173-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating palliative care ward staffing using bed occupancy, patient dependency, staff activity, service quality and cost data. Palliat Med. 2013;27:123-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40:899-911.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Supply, Demand and use of Palliative care Physicians in the US: A Report Prepared for the Bureau of HIV/AIDS, HRSAle. ” Albany, NY Center for Health Workforce Studies 2002

- [Google Scholar]

- End-of-life care at academic medical centers: Implications for future workforce requirements. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25:521-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Community-based palliative care leader perspectives on staffing, recruitment, and training. J Hospice Palliative Nurs. 2018;20:146-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Workforce issues in palliative and end-of-life care. J Hospice Palliative Nurs. 2007;9:334-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Few hospital palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:1690-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Workforce Development and a Regional Training Program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:138-43.

- [Google Scholar]