Translate this page into:

A Study to Assess the Feasibility of Introducing Early Palliative Care in Ambulatory Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer

Address for correspondence: Dr. Vanita Noronha, Department of Medical Oncology, Tata Memorial Hospital, Dr. E. Borges Road, Parel, Mumbai - 400 012, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: vanita.noronha@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Purpose:

Early palliative care is beneficial in advanced lung cancer patients. We aimed to assess the feasibility of introducing early palliative care in ambulatory advanced lung cancer patients in an Indian tertiary cancer center.

Methodology:

In a longitudinal, single–arm, and single-center study, fifty patients were recruited and followed up every 3–4 weeks for 6 months, measuring the symptom burden using Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) and quality of life (QoL) with European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-QoL tools. The primary end point of feasibility was that at least 60% of the patients should complete 50% of the planned palliative care visits and over 50% of the patients should complete QoL questionnaires. Analysis was done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.

Results:

Twenty-four of fifty patients (48%) completed the planned follow-up visits. All patients completed the questionnaires at baseline and 31 (62%) at their follow-up visits. The patients’ main reasons for not following up in the hospital palliative care clinic were logistics and fatigue. Tiredness, pain, and appetite loss were the highest rated symptoms at baseline (ESAS scores 3, 2.2, and 2.1, respectively). Improvement in pain and anxiety scores at follow-up visits 1 and 2 was significant (P < 0.05). Scores on QoL functioning scales improved during the follow-up period.

Conclusions:

We did not meet the feasibility criteria for the introduction of early palliative care in our advanced lung cancer patients in a resource-limited country.

Keywords

Advanced lung cancer

early palliative care

feasibility

tertiary care

INTRODUCTION

Patients with advanced lung cancer have unmet needs with reference to physical and psychological suffering, experiencing more psychosocial distress. They are a population of patients that require comprehensive cancer care with maximum palliation as early as possible. Thus, palliative treatment options for this group of patients have focused on hospice or end-of-life care. Two important developments have brought about a change in the pattern of palliative care for these patients and their caregivers. First, advances in management strategies include new drugs with fewer toxicities, allowing more patients to receive multiple lines of chemotherapies.[1] Second, the scope of palliative care in oncology has shifted from being applied only at the cessation of disease-modifying treatment to an integrated model across the cancer trajectory with comprehensive, multidisciplinary care focusing on needs of the patients and their caregivers.[2]

Components of early palliative care include comprehensive history and evaluation, with a focus on patients’ symptoms of concerns, sensitive communication and exploration of patients’ understanding of illness, psychosocial and spiritual assessment, caregiver support, and collaborative decision-making. Early palliative care has proved to have a positive impact on symptom burden and quality of life (QoL) and has been shown to improve survival.[34] A landmark randomized clinical trial conducted by Temel et al. in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer showed a greater improvement in mood and QoL in the intervention arm of early palliative care as compared to standard care.[5] A comprehensive recent review has reported the benefit of early palliative care on patients’ symptom burden (physical and psychological), QoL, advance care planning, end of life care, and health-care costs.[6]

Globally, 75% of lung cancer patients present with advanced disease and receive treatment with palliative intent. There is a need for introducing palliative care early in their management plan. Approximately 70%–80% of the lung cancer patients who visit our hospital, a city-based major tertiary care cancer center, receive therapy with palliative intent and experience significant physical symptoms and psychosocial distress at diagnosis, which continue throughout treatment, maximum severity being at 3 months immediately before death. However, most of these patients get referred to palliative care services late in the disease trajectory, after all disease-modifying treatments have ceased. Furthermore, as our cancer institute is a tertiary referral center, many patients return to their hometowns without the benefit of access to palliative care services in our center or locally. Early palliative care would be beneficial to these patients.

The primary objective of our study was to assess the feasibility of introducing early palliative care in ambulatory patients with advanced lung cancer. The secondary objective was to determine the symptom burden and QoL at baseline and follow-up over a period of 6 months.

METHODOLOGY

The study design was a longitudinal, single–arm, single-center-based study. It was carried out in the Department of Palliative Medicine in a tertiary oncology teaching institute. The inclusion criteria were patients with (1) advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer (Stage IV), (2) performance status of 0, 1, or 2 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale, (3) able to adhere to follow-up schedule at the hospital, (4) age more than 18 years, and (5) able to give written informed consent. Patients with ECOG of more than 2 and expected survival of <4 weeks were excluded from the study. The study was conducted after approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee and was registered with Clinical Trials Registry-India (CTRI/2013/11/004128).

Sample size

Approximately 1000 patients of lung cancer are treated in our hospital per year. Nearly 70%–80% of them have advanced disease and receive therapy with palliative intent. We set our sample size as 50, based on a similar feasibility study done by Temel et al.[7] We estimated that fifty patients could be enrolled over a 4–6-month period. These patients were to be followed up for 6 months; hence, we planned to complete the study within 1 year.

Study procedure

All patients presenting to the department of medical oncology at our hospital were screened for eligibility. Patients fitting the eligibility criteria and consenting for the study were enrolled on the study. The patients met the palliative care team, consisting of the palliative care physician and nurse, social worker, clinical psychologist, counselor, and psychiatrist on the day of the referral from the thoracic medical oncology clinic and on a 3 weekly to monthly basis thereafter for 6 months. The patients or the palliative care clinician could request and schedule more frequent visits at their discretion. If study patients were admitted to the hospital during the course of the study, the palliative care team saw them on a daily basis throughout their admission.

The protocol followed once the patient was referred for early palliative care to the Department of Palliative Medicine is as follows:

-

Registration in the service - A palliative care registration number was provided for future reference, and a contact card was given which listed five telephone numbers for contact details (three doctors + one nurse + one medical social worker) for out of hospital and after hours assistance

-

Assessment of the nursing care needs

-

Assessment of psychosocial needs by the medical social worker or counselor - counseling specific to the situation of early palliative care included sensitive empathic communication eliciting patient's and caregiver's understanding of the disease stage and possible treatment options, understanding patient's and caregiver's physical, emotional, spiritual-existential concerns and fears, noting sources of support for the patient/caregiver dyad

-

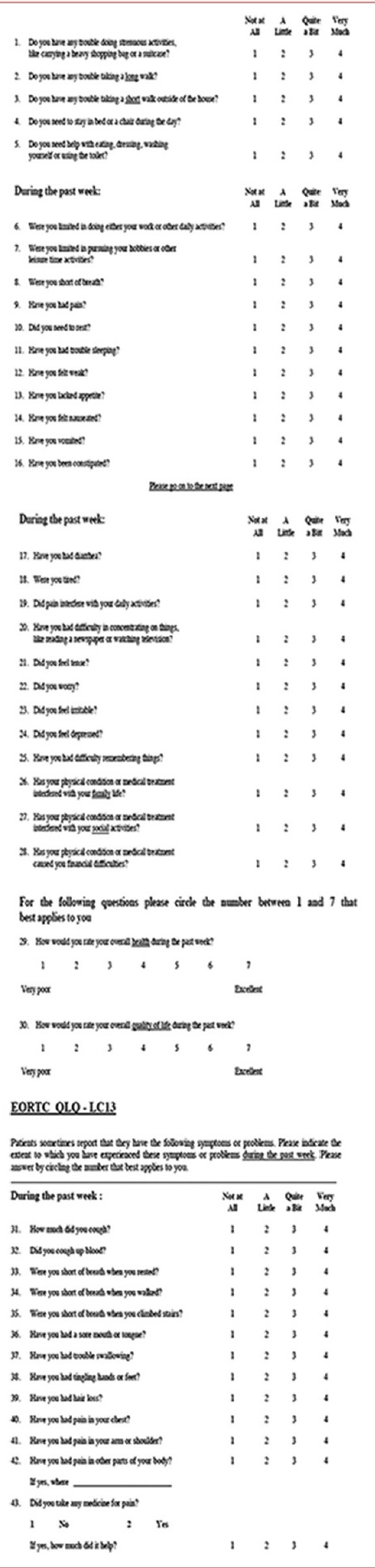

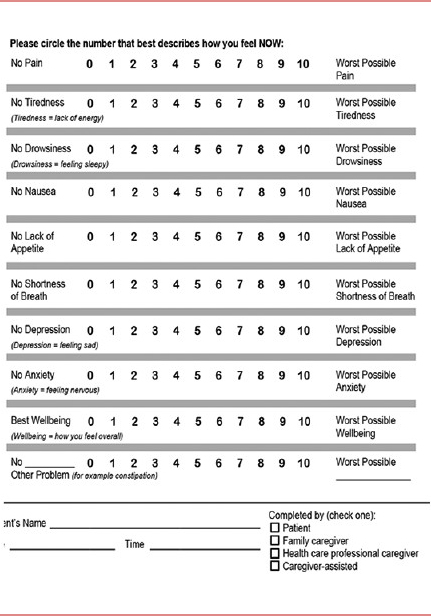

Detailed medical assessment – management of pain and physical symptoms with completion of (a) Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) - ESAS measures 9 being most common symptoms in cancer patients, 0 being absent, and 10 being worst possible severity [Appendix 1][8] and (b) QoL assessment using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-QoL tools (EORTC-QOL QLQ C30 and for Lung Cancer 13) [Appendix 2][910]

-

Formulating a comprehensive management plan according to goals of care

-

Enrolling the patient on our home-based palliative care services if the patient was within the geographic territory of this service provision.

Communication with patients and their caregivers and psychosocial and spiritual history-taking are integral components in the palliative care assessment. Patients undergo nursing assessment too. A palliative care plan is established at the end of the detailed evaluation process. The above details were recorded in the medical record sheet. The problem list, interventions given, and referrals to other care providers, as appropriate were noted.

For the follow-up visits, medical and nursing assessments were done, and psychosocial issues were addressed. The checklist of problems, medications given, and drug compliance were checked. Adequate referrals to other care providers were given as and when needed. These were recorded in the palliative care case records.

The outcome measures were (1) at least 60% of the patients would be able to complete 50% of the planned palliative care visits, i.e., 32 patients should be able to complete 50% of their planned palliative care visits and (2) >50% of the patients would be able to complete ESAS and EORTC QLQ C30 and LC 13 questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for overall descriptive statistics. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyze differences in symptom scores between follow-up visits. To compare the improvement using nominal data, Chi-square test was applied. Analysis was done using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

RESULTS

Sixty-eight patients were evaluated for participation in the trial over a period of 6 months. Eighteen patients did not consent, the main reason being the patients’ uncertainty about their ability to adhere to the follow-up schedule. Fifty patients, therefore, were included in the study over a 6-month period from November 2013 to May 2014, and the follow-up period extended for 6 more months. Baseline characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Twenty-four patients (48%) completed the planned follow-up visits. The details are as depicted in Table 2a.

After the initial visit, 11 patients did not follow up at the hospital at all and 15 patients attended the thoracic medical oncology clinic but did not go to the palliative medicine clinic. The main reasons provided by the patients who did not attend any follow-up were inability to stay in the city, which led them to continue their treatment in their hometown. The reasons given by the patients who came to the hospital for chemotherapy but did not keep their appointments with the palliative care team were that they were busy receiving their chemotherapy and were too late to attend the palliative care services clinic.

Fifty patients completed ESAS and EORTC QLQ C30 and LC 13 questionnaires at baseline assessment. Thirty-one patients (62%) completed the questionnaires at their planned follow-up visits.

Symptom burden at baseline is outlined in Table 2b. Tiredness, pain, and appetite loss were the most distressing symptoms. Table 3 depicts the change in symptom scores at each visit. On ESAS, improvement in pain and anxiety scores at follow-up visits 1 and 2 was significant. Tiredness changed only at the first follow-up visit, whereas a significant improvement in shortness of breath occurred at follow-up visits 1 and 5.

There was an improvement in the functioning scales and overall QoL [Table 4]. On the symptom domains of EORTC QLQ C30 and the lung cancer module, there was a trend for improvement in all scores, except for nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and tingling, in which there was a slight increase. However, the change was not statistically significant. Survival at the end of 6 months was 64.7%.

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to assess the feasibility of instituting palliative care early in the management of advanced lung cancer at our center in a resource-limited setting. Fifty patients, recruited over a 6-month period, were followed up for a period of 6 months. Our early palliative care intervention included the components which have been followed in other studies.[11]

Twenty-four out of fifty patients (48%) completed 50% of the planned follow-up visits. This was <60% target that we had set for establishment of feasibility of early palliative care. In the earlier feasibility study done by Temel et al., the feasibility criteria were met in 90% of the patients.[7] Several reasons may explain why we were unable to attain the primary end point of feasibility of early palliative care. First, the health-care service model in India differs from that in the United States of America. Our study setting was the palliative medicine outpatient clinic in a tertiary care oncology institute where patients come for comprehensive cancer care from all parts of the country. The model of each hospital having its own catchment area, as is the practice in developed nations, does not apply to our setting. Our inclusion criteria were not restricted to patients based only on the city, in which our hospital is based. One of our inclusion criteria was patients willing to adhere to the follow-up schedule at our hospital, and all the patients agreed to this criterion and provided written informed consent. However, patients with advanced lung cancer were sick and once they understood that their expected survival was limited, and they started experiencing disease-related and therapy-related symptoms, they may have changed their initial decision of taking treatment at our hospital, and may have returned to their hometowns to continue therapy locally. This was one of the reasons that the patients gave, which led to difficulty in completion of follow-up visits in our hospital. A second reason for nonattendance reported by some of the patients was chemotherapy-induced fatigue and hence, inability to attend multiple clinics. Finally, patients’ and caregivers’ perception of palliative care in our setting possibly differs from that in other regions. Kain has described patient- and caregiver-related obstacles to executing early specialist palliative care, one of which is a lack of awareness regarding palliative care.[12] There is a lack of awareness about palliative care in general, which is possibly equated with end-of-life care.[13] This bias could have caused barriers in patients’ attendance at the palliative care clinic, despite adhering to appointment schedules at the primary team's appointments in the thoracic medical oncology services where treatment may have been perceived to be more important. The concept of early palliative care was new to our setting.

All fifty patients in our study completed their ESAS and EORTC QLQ C30 and LC13 at baseline. Thirty-one (62%) patients completed these questionnaires at their planned follow-up visits. This was higher than the 50% cutoff, which we had set as an outcome. Our experience was that patients and caregivers were happy with their clinician's interest in their physical and QoL concerns, and hence they willingly filled out the QoL assessments. Other studies have discussed difficulties faced in palliative care research including high attrition rates and poor compliance with study questionnaires.[141516]

The symptom burden was low in our study. Tiredness, pain, and appetite loss were the highest rated symptoms at baseline, with all scores being in the mild range. The low symptom burden has been noted in randomized studies by Bakitas et al. and Zimmermann et al.[1718] As regards the change in symptoms over the course of follow-up, pain, tiredness, and anxiety improved significantly in the initial follow-ups (1st and 2nd) and shortness of breath decreased in the initial as well as later visits (1st and 5th). In Temel et al.'s study, almost 70%–85% of patients were asymptomatic or less symptomatic at baseline, and the lung cancer symptom scores were relatively stable over the review period.[7] A similar observation was reported in another study.[19]

In the QoL assessments, the mean scores on domains on the functioning scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, social, and overall QoL) improved through the follow-up period. On the symptom domains, fatigue and appetite loss were the highest scores at baseline, as seen earlier on the ESAS scores. Although there was a progressive decrease in most of the symptoms, there were more fluctuations in nausea and vomiting and dyspnea, with a very slight increase in the mean scores at the last assessment. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the mean scores in between visits. Gade et al.'s study in 2009 on palliative care intervention in inpatients had not noted any difference in QoL between the intervention and control arms.[20] The overall QoL scores in the earlier feasibility study also had not changed much.[7] The ENABLE III trial also did not report significant improvement in QoL.[21] In a recent randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of early specialist palliative care in patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancers, though there was a significant difference in QoL from baseline to 24-month period for lung cancer patients, this improvement was not seen in those with gastrointestinal cancers.[22]

There were several limitations in our study, some of which have already been outlined. The main challenges faced by us were (1) recruitment of patients from outside of the metropolitan boundaries of the city of Mumbai, (2) fatigue experienced by patients on chemotherapy limiting their attendance at the palliative medicine clinic, which is situated in the hospital block away from the thoracic oncology clinic or day care area, and (3) patient and caregiver perception of palliative care in our country. The use of broad eligibility criteria is advocated for palliative care trials, which we followed.[14] However, more stringent criteria about recruiting only local patients who could have been followed up by our home-based palliative care team would have circumvented the problem of poor attendance and helped with the completion of assessments and follow-up questionnaires. Furthermore, since early palliative care is not yet a well-established concept in our country, along with a lack of awareness of palliative care in general among lay public and clinicians, better communication strategies such as information leaflets may have helped. Having a dedicated nurse for recruitment would have been of benefit for recruitment and adherence to study visits. The above-mentioned steps are some measures we plan to take forward in future studies.

Despite the difficulties we faced, our study is the first one in the setting of a developing country to assess the feasibility of introducing early palliative care in ambulatory patients with advanced lung cancer. Although we did not satisfy our feasibility standard, it should also be considered that the target of 60% patients completing 50% of the planned follow-up visits, assessments, and questionnaires to meet the feasibility criterion was arbitrary. Hence, for our setting with all the challenges faced and noted earlier, 48% patients being able to complete the planned follow-ups may be an acceptable one.

CONCLUSIONS

In this first study of assessment of feasibility of the introduction of early palliative care in patients with advanced lung cancer in a developing country, 48% of the study population met the feasibility criteria, which was < 60% target that we had set. The patients had a low symptom burden at baseline, and there was a trend toward improvement in symptoms, with significant differences in tiredness, pain, anxiety, and shortness of breath in a few of the follow-up assessments. Although there were no statistically significant differences in QoL assessments over the study period, the trend was toward improvement in both functioning and symptom domains.

Future directions

Various organizations such as American Society of Clinical Oncology have recommended including palliative care as part of a comprehensive cancer care plan from the time of diagnosis of metastatic or advanced cancer.[2] Integration of palliative care with disease-directed therapy in oncology care could be of benefit to patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.[2324] We, therefore, need to focus on the ways to do so, in any setting, clinical, or research.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Staff in Department of Palliative Medicine and Thoracic Oncology Disease Management Group.

REFERENCES

- Second-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: New developments for tumours not harbouring targetable oncogenic driver mutations. Drugs. 2016;76:1321-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early implementation of palliative care can improve patient outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(Suppl 1):S3-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: How to make it work? Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:342-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care consultation service and palliative care unit: Why do we need both? Oncologist. 2012;17:428-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integration of early specialist palliative care in cancer care and patient related outcomes: A critical review of evidence. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:252-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phase II study: Integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2377-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- The EORTC QLQ-LC13: A modular supplement to the EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:635-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:459-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: Evidence and overcoming barriers to implementation. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:374-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of palliative care in India: An overview. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12:241-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methodological and structural challenges in palliative care research: How have we fared in the last decades? Palliat Med. 2006;20:727-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- What influences participation in clinical trials in palliative care in a cancer centre? Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:621-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overcoming recruitment challenges in palliative care clinical trials. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:277-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrating palliative care in lung cancer: An early feasibility study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19:433-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:834-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early specialty palliative care – Translating data in oncology into practice. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2347-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Developing a service model that integrates palliative care throughout cancer care: The time is now. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3330-6.

- [Google Scholar]

APPENDICES Appendix 1: Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale

Appendix 2: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-quality of life C30 and for lung cancer 13