Translate this page into:

Body Image and Sexuality in Women Survivors of Breast Cancer in India: Qualitative Findings

Address for correspondence: Dr. Michelle S Barthakur, Clinical Psychologist, Manukau Community Mental Health Centre, Counties Manukau District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand. E-mail: m.s.barthakur@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objectives:

With increasing rates of breast cancer survivors, psychosocial issues surrounding cancer survivorship have been gaining prominence. The following article reports on body image and sexuality-related issues in aftermath of the diagnosis and its treatment in the Indian context.

Materials and Methods:

Research design was mixed method, cross–sectional, and exploratory in nature. Quantitative sample consisted of fifty survivors while the qualitative sample size included 15 out of the 50 total breast cancer survivors who were recruited from hospitals, nongovernmental organization, and through word-of-mouth. Data was collected using quantitative measures, and in-depth interviews were done using semi-structured interview schedule that was developed for the study. Qualitative data were analyzed using descriptive phenomenological approach.

Results:

In body image, emerging themes were about identity (womanhood, motherhood, and attractiveness), impact of surgery, hair loss, clothes, and uncomfortable situations. In sexuality, barriers were faced due to difficulty in disclosure and themes were about adjustments made by spouses, role of age, and sexual difficulties due to treatment.

Conclusions:

Findings imply need to address the issues of body image and sexuality as it impacts quality of life of survivors.

Keywords

Body image

Breast cancer

India

Qualitative

Sexuality

INTRODUCTION

In India, the incidence of breast cancer has increased with urbanization. It has been projected that there will be 250,000 new cases per year by 2015 indicating 3% increase per year.[1] However, with the number of increasing survivors worldwide due to improvements in the treatment modalities of breast cancer, several psychosocial issues have gained prominence. In India, one study has focused on the psychosocial impact of breast cancer treatment.[2] There are no other in-depth studies focusing on breast cancer survivorship. The following article highlights the qualitative findings related to body image and sexuality which are from a larger doctoral study. The larger study had adopted a mixed methods approach in understanding the various quality of life factors that influence breast cancer survivorship trajectory. In the current article, qualitative findings on body image and sexuality have been reported.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study adopted a mixed method design, was cross-sectional and exploratory in nature. The quantitative sample consisted of fifty survivors and the qualitative sample consisted of 15 from within the quantitative sample. These survivors included Indian women from urban communities of Southern and Eastern India. The inclusion criteria of the study were (a) women who have undergone mastectomy/lumpectomy and those currently undergoing hormonal treatment as adjuvant therapy, (b) women in age group of 18 and above, (c) married women, (d) English or Hindi speaking, (e) minimum education of high school completion, and (f) at least 6 months since administration of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The exclusion criteria included (a) women currently undergoing chemotherapy or radiation treatment, (b) women with cognitive impairments, and (c) women with active or distant metastases. Purposive sampling strategy was used.

Data for in-depth interviews were collected from survivors associated with two nongovernmental organizations called (a) Connect to Heal based in Bengaluru and (b) Hitaishini based in Kolkata, St. John's Medical College and Hospital, a private oncology clinic in Bengaluru, and through snowball sampling. Institute's Ethical Committee Board at National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru and St. John's Medical College and Hospital, Bengaluru provided the research approval.

Based on a review of literature, semi-structured interview schedules were developed by researchers, and the draft was given to seven experts for feedback. Participant information leaflets were provided, and informed consent was taken from survivors before the in-depth interviews were undertaken. The participants were informed about the duration of interviews occurring over 2–3 sessions, each lasting 1.5–2 h. These interviews were done at homes and offices of participants and audio recorded after their permissions had been sought. For one participant who refused consent to audio record the interview, detailed notes were made through and after the interview. Interviews were started after providing consent, filling out demographic and clinical data sheet, and quantitative measures. Interviews were done in English and conducted until no new phenomenological information emerged in the interviews.

Data management and analysis

Interview data were analyzed using descriptive phenomenological approach. Husserl[3] explained it as “the science of essence of consciousness.” It utilizes the first person's point of view to focus and understand lived experiences. The memo was maintained to ensure researcher's neutrality toward subject matter through bracketing.

The following steps were used to analyze data:[4]

-

Inq Scribe (a free online software) was used to transcribe, proof-reading interviews, and re-read to acquire broad understanding of experiences

-

Line-by-line reading was done to identify the areas of phenomena that had been captured

-

Statement pertaining to areas of phenomena were assigned meanings

-

Clusters of categories, broader themes, and domains based on identified statements

-

Exhaustive description of phenomena was done based on integrated findings and provided to coresearchers for review

-

Coresearchers' feedback were incorporated to reflect the universal features of phenomena.

RESULTS

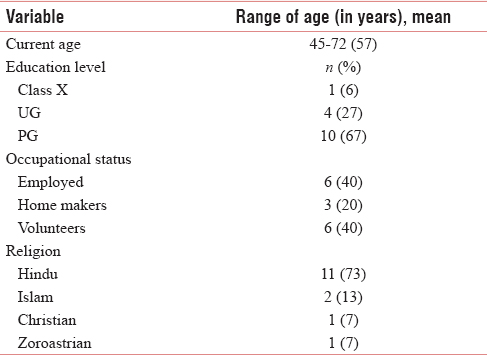

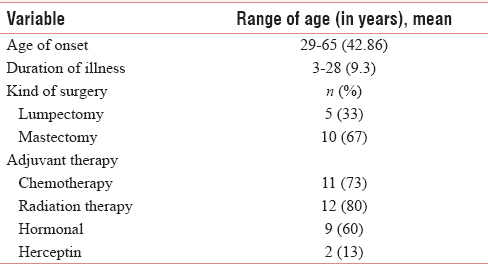

Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics are depicted in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Body image

In the domain of body image, themes focused on impact on identity, surgery-related issues, hair loss, adjustments to clothing, and encountering difficult situations.

Identity: Womanhood, motherhood, and attractiveness

The impact of breast cancer on identity as a woman manifested in several ways: Fear of losing one's breast was common and maximal in days following surgery: “What happens to us females is that it is so difficult when we don't have one breast. That thing can never be explained to anyone…” As treatment ended, use of prostheses or other adjustments made, continued to be a daily reminder about an “empty space.” Another concern expressed by one survivor was the slightest comment by one's spouse about the shape could be distressing. To some survivors, the event of hair loss was most distressing: “…If it was pain I could say I could still bear it… But that again you know many times I used to reflect “okay hair loss fine one day it will just come back maybe we just use a couple of wigs.” One survivor also expressed the cultural expectation that breasts are to be hidden or covered which thereby reduced impact of the loss: “When we were young particularly the breast part… Maybe our community and as well as society at that time was such that you will conceal breast… That's why always one dupatta (scarf) will be there… So losing a breast was not really big thing for me…”

With relation to motherhood, children of most survivors ranged in age from adolescent to adulthood years when they were diagnosed with the illness and it, therefore, did not affect them. However, it had been a matter of concern for those who were diagnosed with it at an early age in terms of breastfeeding, inability to conceive when they wanted more children, or losing all chances of fertility due to the treatment.

In terms of attractiveness, one of the most common beliefs was that “attractiveness is internal” and it was defined as one's behavior and not appearance. Few survivors also expressed attractiveness as important at a younger age. However, few survivors themes suggested a sense of being “cheated by life” as due to cancer, they no longer received “attention” or “make people notice” them after it. The rarer theme was few survivors continued to feel attractive: “I feel quite attractive that way in fact now many people say that after chemotherapy your skin is more clear and there is glow on your face…”

Impact of surgery

In relation to one's appearance postsurgery, a typical theme voiced was the tendency to avoid looking at the mirror after the treatment had been long over: “…For the world, I feel quite okay. Personally I stopped looking at myself in the mirror… I've had the long full-length mirror I used to have in my room. I've removed that now…” One participant reported feeling “self-conscious” and “disfigurish” even after more than two decades of the illness. A variant theme was related to the leukoderma that she developed as a reaction to chemotherapy: “My body is like an atlas (laughs).”

In relation to the scar, the most common theme was of dissatisfaction either with the quality of the surgery in terms of scarring or persisting pain and itching in the site: “I feel it's a cobbler's job. I feel it should have been like embroidery.” However, most of them also become habituated to the scar though they initially experienced distress when looking at it. One survivor's response to her child asking about the scar would be: “I tell her she ate it up as a kid…”

Several survivors had had the experience of others wanting to see the scar. Few of them were not comfortable with it while few others were comfortable showing it to close relatives. As one survivor who also works as a cancer volunteer expressed, it was dependent on the context: “Some people have wanted to see it especially those who are very curious, I did not feel good at all about their curiosity as this is not a matter to be joked about, it is an illness.” But when a patient has said, “Please show it to me. Whatever happened to you, is it same like mine?” Then we show it to them… We show it to them because their curiosity is different, they think, “Mine and hers are same…”

In relation to the shape and size of the breast, there was a typical theme between those who had undergone mastectomy or lumpectomy. For those with lumpectomy, they expressed concern about breasts being “lopsided” and it was accentuated as the survivor aged: “My left side looks young, and my right side due to age, length has become long.” A variant theme was the presence of sensations in the area where the mastectomy had occurred: “You may not touch your breast like that every day but now you're conscious. Now you get a scratchy or if you cut off a leg, don't they say they get sensation at the end of your toe even if your leg is cut off from here?”

Hair loss

Hair loss during chemotherapy was handled either through the use of scarves, wigs, hijab, or going bald. For one survivor, the bald head and the use of a scarf were particularly difficult for her young child: “The shock was with my younger one because she couldn't see me that way and when I used to expose my head in front of her, I always had a dupatta (scarf) on my head while I was at home.” Others either shaved their heads before the chemotherapy sessions began and had wigs made out of it or as one participant said: “I bought a couple of wigs off the net and I would go around in my blonde avatar. Actually got a blonde (laughs) just to kind of cut off your nose to spite your face kind of thing…” One survivor who was of Islamic faith would wear the religious headgear or the Hijab to handle the situation. One survivor expressed the taboo associated with hair loss: “And all those things unnecessarily traditionally or just it becomes a taboo or stigma also. Actually in Islam you don't have but since we are in India, so those things matter a lot.”

Clothes

Themes that emerged in relation to adjustments made for clothes have been divided on the basis of the breast, lymphedema, the chemo port scar, and leukoderma.

Adjustments for those undergoing mastectomies involved using substitutes such as prosthesis, padded bras, and pads. The use of prosthesis on an everyday basis was convenient, but its weight was a concern and others would use pads made out of cloth. In those with lumpectomy, there was a tendency for breasts to be lopsided due to which they reported wearing “baggy” clothes with a scarf or a “dupatta” (scarf) and avoidance of “white clothes.”

With a saree blouse, issues were regarding it's fit as it caused “pain” in the surgery site when worn for few hours and the neckline as there was a fear of the scar being exposed: “when I go to my tailor… I have to show him my scar… Because now when I see this scar on someone else then I know that person has had breast cancer or at least cancer of some sort to have this port cut. Because it's very obvious noh because it's got two lines. You can't miss it… So he has to make sure that the neckline comes this way right or a V?”

In relation to lymphedema, the need for different sleeve sizes was a matter of concern as they had to be stitched in different sizes. The survivor who developed leukoderma, her concerns was more related to it: “I used to wear a lot of sleeveless and very low-necked thing. Now I'm… because of this… I don't wear short sleeves so easily if I'm going out.”

One survivor also expressed reduced interest in dressing style: “Now I feel I will never look good. Never look attractive to people, to men in general… So that parts gone away so now it's just dressing for activity which you do… (laughs) but the other thing will also be that I am not as attractive as I used to be because I can't dress as attractively as I used to.” In contrast, several survivors also reported taking more care than before about their appearance: “When I go out, I take extra care. But… I have make-up on I try to wear nice dress. I have started buying more clothes than I did earlier… So I have something new and just to feel good.”

Uncomfortable situations

In relation to feeling uncomfortable in particular situations due to fears of exposure, it occurred when (a) going for swims, massages, changing clothes others presence, frisked by security personnel, (b) breast accidently collided with someone else in buses or crowded areas: “When I would travel by train or bus and if someone collided, they would stare for a bit because it would feel different because I would wear a prosthesis and you could make out… I always used to cover the area with my bag.”

Another concern was raised in terms of the prosthesis slipping out by few survivors: “Even for swimming it's not possible since it floated out once and I was able to put it back before anyone noticed… When you are holding on top and travelling in a bus, one day the prosthesis came down, but I was able to put it back in its place without anyone seeing…”

Sexuality

Most participants were uncomfortable in sharing details regarding the physiological aspect of sexual functioning or sexual intimacy that are practiced in nonsexual behaviors. The nature of responses was either “no problem,” “there is no sexual intimacy left” or that “there was initial difficulty after the treatment but it's all fine now.” Therefore, some of the presented findings are based on the responses of few survivors. The themes related to sexuality have been divided on the basis of changes due to the treatment, partner's challenges and adjustments made, and attitudes held toward sexuality.

Themes suggested immediately after surgery, few survivors reported that there was difficulty in communication, but spouses were empathetic: “My husband was scared to touch me even. Not because of anything else, he thought maybe you know I'm not ready or… He didn't want to force anything on me. I was just left to myself. It had an adverse effect too. Because I was not frank, he was not frank. So there's lot of tension there in the beginning, but now I feel it's all well past gone.” One survivor sensing her husband's difficulty consulted her physician before resuming sexual activity: “After being cautious for good number of days, I felt he was finding it difficult as males get aroused easily as well as it diminishes fast. Then, I consulted my doctor, he said, 'It is completely normal. Your sexual life is as normal as how it was before the operation. And your worry regarding hurting your breast, it doesn't get hurt.' After that, we had sexual activity, though it was very less.”

As treatment ended and several years had passed, few survivors voiced their concern about a lack of desire to engage in sexual activity and an inability to get aroused which was associated with vaginal dryness and pain. Moreover, one survivor with lumpectomy also expressed a change in her partner's overt sexual behavior in the form of preference for the normal breast.

Few survivors mentioned that the spouse's health also played a role in the cessation of sexual life. Age was often voiced as a common factor for decrease in sexual activity by all older survivors. However, one survivor said they continue to be intimate through affection: “Somehow my husband also more into… Exercises this and that more into spirituality… We have lot of sharing and bonding but not that physical urge to do sex, maybe we hold hand and things like that but no like intercourse as such…”

Another participant had extreme views that sexual life could be equated to “animal life” and it serves the function of procreation purposes.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the current study is to understand breast cancer survivorship trajectory from an Indian perspective. In the current article, there has been an attempt to understand the impact of the diagnosis of breast cancer and its treatment on body image and sexuality issues using qualitative findings of a larger doctoral study.

Qualitative findings of the study provide an understanding about how one experiences challenge on an everyday basis in dealing with body image alterations. The studies with similar findings have shown affects one's identity through its impact on sense of attractiveness, womanhood, and motherhood.[56789] However, in the India context, it is further complicated due to stigma often attached to the diagnosis of cancer and loss of a breast in a culture where sexuality is generally repressed.[10] Varying degrees of habituation to the scar, discomfort in looking at oneself in the mirror and the shape of the breast which affected clothing habits were similar to findings in another study.[5] However, in the Indian context, adjustments to the dressing style with stitching of saree blouse's neckline and the sleeve sizes using a known tailor was associated with less threat of exposure, and saree was preferred as it helped camouflage the breast better. This finding was similar to the study[2] wherein the saree was the preferred choice of clothing. In terms of womanhood, older women experienced a sense of loss of an organ that had nurtured their children, but it was not significant. Similar findings were made in a study done in Iraq which found that older women believed that it had served its purpose and therefore, in terms of motherhood it did not signify an important loss.[9]

The process of body hair loss during chemotherapy has been considered a traumatic experience even though it is temporary in nature. Similar findings have been found in different ethnicities in the West.[7] In India, as based on a survivor's belief, hair loss can induce extreme distress due to the notion that long hair is associated with femininity.[11]

In relation to understanding sexuality, the researcher encountered difficulties in eliciting in-depth data. Most survivors reported feeling discomfort in disclosing information. However, they also tended to attribute it to the factor of old age. Research has also consistently established the same in terms of diminishing sexual functioning with age due to both biological and psychosocial factors.[1213] An interesting psychosocial belief which manifested in the present study “sex life is animal life,” and family tradition of spouses sleeping separately (apart from age being a factor) again alludes to the tendency to repress sexuality by equating it to the function of procreation. Belief about how engaging in sexual activity could cause endometriosis also hints at the lack of awareness. A similar finding was reported in China, wherein survivors were asked by others not to engage in sex due fears of contracting endometriosis.[14] These findings could be explained by the fact that along with cultural repression of sexuality, the free expression, or discussion about sexuality could suggest defying of standard sexual norms of the society thereby, alluding to a sense of immorality within the individual.[15]

Limitations of the study are (a) sample consisted of survivors from urban, educated, and middle socioeconomic level with at least 12 years of formal education. Survivors of rural background, low-income families, and less education levels could have had different concerns, (b) it was a cross-sectional study design with purposive sampling; therefore, self-selection bias could have been present. It does not provide scope to include perspectives of survivors experiences who refused consent, and (c) there was difficulty in understanding sexuality in-depth due to taboos attached to it, ethical considerations, and the fear of rupture of alliance between the researcher and the participant.

Strengths of the study include (a) it is one of the first Indian studies to focus on body image, and sexuality in breast cancer, (b) all interviews (except one) was audio taped after the consent of the participants, and (c) the study illustrates certain similarities in findings with Western literature and the role of Indian culture in understanding sexuality.

The findings provide directions to help formulate interventions designed to address body image issues of breast cancer survivorship.[16171819202122]

Research implications include replicability of the study to rural contexts with survivors from low-income and less education backgrounds and including spouses to gain understanding about its impact on them.

CONCLUSION

The findings highlighted above suggest breast cancer survivors can experience various forms of body image issues and difficulties in sexuality as a consequence of breast cancer treatment. Overtime, most survivors tend to find various ways to deal with body image related issues though improvements can be made in services geared towards helping them cope with treatment related changes. However, in terms of sexuality, due to the taboo attached to it, it will require innovative ways to firstly understand the difficulties experienced followed by designing interventions to address them.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Psychosocial disorders in women undergoing postoperative radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer in India. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47:296-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Logical Investigations. New York: Humanities Press; 1970.

- Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In: Valle RS, King M, eds. Existential Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology. New York: Plenum; 1978. p. :48-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accept me for myself: African American women's issues after breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:875-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of the effects of lumpectomy versus mastectomy on sexual behaviors. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:279-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African-American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13:408-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial Impact in the Areas of Body Image and Sexuality for Women with Breast Cancer. Sydney: National Breast Cancer Centre (Australia); 2004. p. :67.

- Adjustment process in Iranian women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:E32-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Article for special supplement of Indian concepts on sexuality on Indian mental concepts. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:250.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women in India: Femininity and Sexuality. c2013. Flamingo Mumbai. Available from: http://www.flamingogroup.com/files/fyi/womeninindia.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Sexuality in older age: Essential considerations for healthcare professionals. Age Ageing. 2011;40:538-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- A neglected issue on sexual well-being following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment among Chinese women. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74473.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sexual behavior of married young women: A preliminary study from North India. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:163-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:35-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mindfulness in sex therapy: Applications for women with sexual difficulties following gynaecologic cancer. Sex Relation Ther. 2007;22:3-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behaviour Change. New York: The Guildford Press; 1999.

- The Behavioral Treatment of Sexual Problems: Brief Therapy. New York: Harper & Row; 1976.

- Education and peer discussion group interventions and adjustment to breast cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:340-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:276-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women's sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J. 2009;15:48-56.

- [Google Scholar]