Translate this page into:

Death in the Hospital: The Witnessing of the Patient with Cancer

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sartor SF, Mercês NNA, Torrealba MNR. Death in the hospital: The witnessing of the patient with cancer. Indian J Palliat Care 2021;27:538-43.

Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of the study was to know the witnessing of death from the perspective of the cancer patient in the hospital environment.

Materials and Methods:

This is a qualitative and descriptive study, which was carried out in a cancer hospital in southern Brazil, with 27 cancer patients, through semi-structured interview, after the institutional research ethics committee approval. For categorisation and data analysis, Iramuteq software and Creswell content analysis were used.

Results:

Six classes emerged from the Iramuteq software and four categories were formed: (1) The reflection of the other itself; (2) feelings and emotions aroused; (3) the witnessing of a peaceful death and (4) death as a habitual event.

Conclusion:

Patients felt sad and distressed, and some perceived death as something natural, often necessary for the relief of suffering. They put themselves in the place of the dying patient and their family members, imagining their loved ones and the suffering they would experience. Participants considered peaceful deaths to be good, unlike those in which patients had some kind of discomfort, described as horrible, distressing, sad and bad.

Keywords

Attitude to death

Death

Oncology nursing

Oncology service hospital

Perception

INTRODUCTION

It is known that death mobilizes several emotions. Anxiety, sadness, feelings of frustration and helplessness[1,2] may appear after the diagnosis of cancer, which in the social imaginary is associated with a death sentence.[3,4] Increasing cancer incidences in recent years and its high mortality rate may justify it, for the disease is the second leading cause of death worldwide, responsible for about 9.9 million deaths in 2020.[5,6]

Throughout illness and treatment, the cancer patient may need hospitalisations[7] to control and remit the disease and rehabilitate health. However, hospitals may also expose patients to death in daily life. Therefore, the patient can witness the death of other patients, whose diagnosis and prognosis may be similar.

Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one study, which was carried out in the United Kingdom in 1996, which evaluated anxiety and depression in patients who witnessed the death of other patients in hospice. In the assessment, patients had lower rates of depression and anxiety when compared to those who did not witness death.[8] This result reflects the care environment, supported by the philosophy of palliative care, with adequate control and management of symptoms. However, in other studies, death for cancer patients arouses anxiety, fear and insecurity in the face of the unknown.[9,10]

In contrast, in our study, a different scenario and population are presented. Thus, the results bring perspectives about death and dying when embracing the death witnessing at the hospital. In addition it promotes reflections for both cancer patients and professionals working at the time of death. Thus, it is possible to have theoretical-reflective support for nursing practice and other areas of health regarding death.

This study had as its research question: How does the cancer patient witness death in the hospital environment? Hence, the purpose of this study was to know the witnessing of death from the perspective of the cancer patient in the hospital environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

It is a descriptive study with a qualitative approach, which was based on the script of the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research of the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research network.[11] It was carried out in two adult inpatient units of an oncology hospital in the state of Paraná, Brazil, which assists clinical, surgical and palliative care patients. The study’s approach allows knowing the meaning that cancer patients attribute to witnessing death since it starts from individual premises, singular ways of understanding the world.[12]

Participants

Of the 30 eligible patients, indicated by the nursing, medical and administrative team, 27 accepted to participate in the research and three refused, for they did not express interest. The participants had cancer and witnessed the death of other cancer patients in the hospital. The study used the convenience sample, which determines the population to be studied from the characteristics that the researcher intends to analyse.[12]

Participants aged over 18 years, diagnosed with cancer at any stage and in any treatment modality were included. Those with lower levels of consciousness and emotional disorganisation were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Data collection happened from December 2019 to March 2020 after a face-to-face contact approach. The researchers created two instruments: The participant’s socio-demographic and clinical profile and the semi-structured interview script. To start the interview, the main researcher asked the question: How did you feel witnessing the death of another patient?

The main researcher interviewed and recorded the participants’ narratives, on a date and time previously scheduled, in the inpatient units, which had two to five beds. The interviews lasted an average of 10 min and were conducted in a private environment.

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of the Hospital Erasto Gaertner, Paraná, Brazil approved the research and the ethics code is 20721719500000098. This study respected the ethical precepts of Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council of the Brazilian Ministry of Health.[13] Each informant was recognised by a research code: P (participant); X (Arabic numbers in ascending order of respondents); F or M (female or male) and I (corresponds to the hospitalisation unit). All those who agreed to participate in the study obtained written informed consent.

Data analysis

A six-step content analysis method was used for data analysis.[12] The first stage: Organisation and preparation of data for analysis - the interviews were fully transcribed. The second stage: Reading of the transcribed interviews in its entirety. The third stage: Iramuteq software coded and processed data, which resulted in six classes. The fourth step: The data were described based on the assigned coding. Categories and subcategories were created derived from Iramuteq and the data. Fifth stage: Iramuteq generated graphic representations from the participants’ narratives, resulting in the similarity analysis and word cloud (minimum Chi-square of 3.4 and P < 0.0001). The sixth stage: Interpretation of the analysis. The meanings extracted were interpreted and correlated with the existing literature.

RESULTS

Of the 27 participants, 16 were female, lived in the city of Curitiba and in the metropolitan region, in the State of Paraná, Brazil. They are predominantly white, Catholic, married, with two to three children and had low education. As for the participant’s primary caregiver, they were family members and spouses. In relation to occupational and/or professional activities, they were on sick leave for cancer treatment (n = 16), retired (n = 4), domestic workers (n = 3), commerce workers (n = 3), from home (n = 3) and bricklayer (n = 2). In the clinical variables, 12 participants had a diagnosis of haematological cancer and 15 had solid tumours; seven were in Stage IV cancer, with bone and lung metastasis. Regarding treatment, 18 participants underwent chemotherapy, five went through radiation therapy and 15 underwent surgical procedures. From the interviews, six classes emerged that formed four categories: ‘The reflection of the other itself;’ ‘Awakened feelings and emotions;’ ‘The witnessing of the peaceful death’ and ‘Death as a habitual event.’

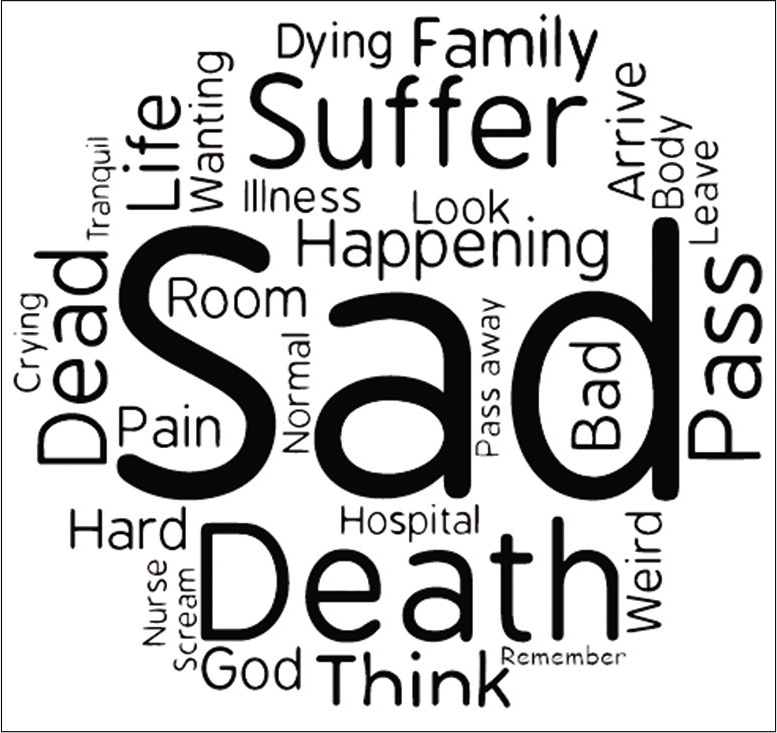

The dendrogram and word cloud may be observed in [Figure 1] and [Figure 2].

- Dendrogram generated by Iramuteq.

-

Source: Iramuteq.

- Word cloud.

-

Source: Iramuteq.

In Classes 1 and 2, the participants reported how witnessing death made them reflect on the experience in their lives. In Class 3, the witnessing was expressed as something normal, habitual, common and expected in the hospital environment. In Classes 4 and 6, patients described the feelings and emotions aroused from the witnessing, such as sadness, anxiety and distress. In Class 5, they described how the way in which death occurs affects the way they see it.

The witnessing of death was described in two ways one as something normal, natural and peaceful. The other way describes death as something painful, shocking, manifested and intensified by the desire to leave the hospital room, where the witnessed death occurred. They also described the pain and the suffering experienced by the family, which adds the meaning of a sad event. On the other hand, they considered death as a normal event when it happened without pain and was supported by the family. Nonetheless, the participants who used words like ‘natural,’ ‘normal’ and ‘peaceful’ were those who used other words to describe ‘death,’ such as ‘pass away’ and ‘gone.’ This may be an attempt to distance death, for it is normal or natural for other people and not for themselves who speak.

The word cloud shows the words mentioned by the participants. The words ‘sad’ and ‘death’ are more frequent, followed by the words ‘dead’ and ‘dying.’ Other words express the participants’ general perception of the witnessing of death, such as: ‘Suffer,’ ‘pain’ and ‘bad,’ which implies an idea that death and its witnessing is an unpleasant moment.

The classes and categories generated by the Iramuteq software are shown below, in [Figure 1] and [Figure 2].

Classes 1 e 2: The reflection of the other in oneself

In this category, the participants demonstrated how the death of the other affected their lives, reflecting it in themselves and in their lives.

‘It is bad to see a person dying in front of you, with the same problem as yours. (...)Unfortunately, it was her, but it could have been me, and that’s a bad thing’ (P2mB)

‘I was thinking, and I am also on the same path. Will my death be like this?’ (P6fB)

‘I keep thinking that I also have this disease. So it gives me more strength. It was an incentive for me to remain firm in my treatment.’ (P8mA)

Witnessing the death of another affects the lives of cancer patients, positively or not. Part of the participants reported imagining themselves in the place of the patients who had died, mainly because they had the same diagnosis. After that, they started to ponder about their own death and what would be their family members reaction to the situation. These thoughts generated fear, insecurity and anxiety when they realised they were probably on the same path. Therefore, witnessing the death of other patients was a trigger for insecurity and sad thoughts.

On the other hand, for some, witnessing the death of other patients was a source of strength and encouragement to fight against the disease and for life. This fact is interesting since most people try to isolate death and, controversially, it can be a potential catalyst for life. When faced with the reality and facticity of death, some participants expressed a greater desire to live and remain in treatment.

Class 3: Death as a habitual event

Some participants stated that they are used to the death of other patients, which, for them, is a common event. For some, it has become easier over time, yet, for others, death is still difficult to witness.

‘I have been through this more than once, and it has become habitual; it occurs every time I come to the hospital.’ (P2mB)

‘It was normal, he was waiting, he was suffering, sighing a little, and it was difficult for him.’ (P7mA)

‘(...)I was calm. There were health professionals there, and if they couldn’t solve it, there was nothing else to do.’ (P20mA)

Death appears as something natural, for the various deaths witnessed, or for the thought that nothing else could have been done. It applies the idea that death is about suffering and that is how it tends to be. This thought triggers the thinking about normalisation, not of death, but of the suffering that can come, yet should not come, with it.

Classes 4 e 6: Feelings and emotions aroused

In this category, the participants expose their feelings and emotions aroused from witnessing the death of the other patient.

‘I did not like seeing it. It made me sad. I wanted to leave the room. Change rooms. I did not like to see the nurses rolling the body. I felt bad. It’s sad it has an end, it wasn’t pleasant.’ (P3fB)

‘It was unpleasant, seeing the person suffering and not being able to do anything. He suffered until his little heart stopped.’ (P12fB)

‘I can’t understand. I feel sad and hurt because I do not think it is fair. Looking at someone who is struggling, and nothing can be done, not even a prayer works out, no medication solves. It makes me very insecure. I find the saddest thing to be witnessing death while I am fighting for life. (...)I start to think that there is no point, that the end is the same for all of us.’ (P16fB)

There are different feelings, emotions and attitudes, which are awakened when witnessing death, such as fear, hurt, fragility and an attempt to not suffer. The feeling of sadness was predominant when the death occurred with signs of suffering and discomfort, with episodes of emesis and groans that indicated pain. The participants wished to leave the room or for the health team to isolate the ones at the end of life. Isolation emerged to protect oneself from the pain or the discomfort experienced.

Others expressed fear of being affected by depressive thoughts triggered by the death they had witnessed. A barrier was created to avoid reality and the facticity of the disease that threatens life, not seeing death as a real possibility, in an attempt to remove it and everything that involves it.

Class 5: The witnessing of a peaceful death

Death and the way it happens affect everyone, not only the patient himself, his family, but also the other patients present at the time of the death.

‘She left without any pain, without suffering. Her little heart just stopped. It was a very calm death. I consider that a good death because she did not even feel it, she did not have that agony, she did not struggle, her heart just stopped. It was a peaceful death.’ (P25fB)

‘The patient was at peace, very calm, from the time she arrived until the time she left.’ (P27fB)

When the other’s death was described as peaceful and serene, the participants perceived it as positive. A good death can lead them to have a better perception of the finitude of life and it ceases to be tragic, naturally becoming a part of life. It is essential to ponder on the importance of care at the end of life and provide a good death, not only for the patient, who is at the end of life, but also for the patients who witness the death of others throughout hospitalisations.

DISCUSSION

Participants in this study witnessed the deaths of cancer patients in their hospital room. Those who witnessed more than three deaths had a more natural view of the end of life. They described it as a passage, the last lifecycle, reporting feeling comfortable with the situation and with the health team performance at the time of death. It is possible to observe the naturalisation of the event and the awareness of one’s finitude.

Even considering a different population, in a Brazilian study carried out with nursing professionals on the perception of the ritual after death, the results show sadness and hopelessness during the preparation of the body, associated with the professional bond. Depending on how strong or significant the bond was, the nurses felt more shaken. This reaction was more frequent in professionals who had <5 years of professional experience and had prepared fewer post-mortem bodies.[14]

On the other hand, in a study in Turkey, with health professionals, the fear of death decreased with the time of experience and the successive rituals of preparing the body after death.[15] Similarly, in our study, participants who witnessed fewer deaths in the hospital environment experienced more stressful emotional symptoms, such as sadness, hopelessness, fear and anxiety.

A study carried out in England,[8] with patients from a hospice, states that when patients witnessed the death of other patients, they presented lower rates of depression and anxiety, when compared to those who had not witnessed deaths. However, it is important to highlight that probably death was considered good, for the patients were in a health service that has human and material resources to provide good deaths.

In our study, participants were undergoing cancer treatment and were assisted by the onco-haematology service and expressed sadness, anguish and anxiety at the witnessing of death. Only those who witnessed more than three deaths in the hospitalisation period perceived it as natural, which makes one think that the continuous exposure to deaths can lead the moment to a certain ‘normalisation.’

Furthermore, it is necessary to reflect on the importance of the interdisciplinary team being prepared to work with the philosophy of good death.[16,17] The management of symptoms that generate suffering and signs of discomfort need to be properly managed. Establishing a holistic intervention that guarantees the patient’s physical, psychological, social and spiritual well-being needs to be defined. The relief of physical symptoms must be of particular importance,[17] not only for the end-of-life patient and his family but for the other patients present at the time of death.

In this study, some participants witnessed the deaths of patients who did not have adequate symptom management, with signs of discomfort that needed relief. This led to the witnessing of difficult deaths, leading them to bad and sad prospects about finitude.

Correlating between assisting death and the stages of the death and death process,[18] the phase of anger and depression were observed in some participants, being reinforced by the discomfort they often felt. Likewise, in a Thai study,[19] it was observed that feelings and emotions like those expressed by the participants of our study could be triggered. It happens, especially, when they are unaware of their diagnosis or know about their prognosis, yet have difficulty accepting it.

Conversely, when the participants witnessed good deaths, that is, those who had adequate management of symptoms - for example, ‘died like a bird’ - the event was not strenuous. In other words, from the moment that death is dignified, cancer patients can reformulate concepts, beliefs and modify the perception around the disease worsening process and the consequent finitude.[20,21]

Limitations

This study has limitations and it concerns the physical and psychological condition of the participants, who, at times, declared to be tired. This may have influenced the depth and deepening of the responses. Moreover, there is a lack of studies on the perceptions of cancer patients regarding the witnessing of death, which may have weakened the discussion of results in certain points. In addition, data collection was interrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic, due to the risk of exposure in the researcher’s inpatient wards. As a result, the number of participants may have been a limiting factor.

CONCLUSION

Patients who witness deaths are directly affected by how patients die and it affects the perception of death, life and treatment. For some, the death of the other represented an incentive to remain in treatment more faithfully. Thus, death could be seen as a potential catalyst for life and awaken a new perspective on considering it an event to be hidden.

For further studies, it would be interesting to identify the impact of the death witnessing in other health centres and other locations, with different services, for comparison and exploration of the topic addressed.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Death talk and relief of death-related distress in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10:e19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between the predicted risk of death and psychosocial functioning among women with early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;186:177-89.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions of cancer as a death sentence: Tracking trends in public perceptions from 2008 to 2017. Psychooncology. 2020;30:511-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Experience of people with advanced cancer faced with the impossibility of cure: a phenomenological analysis. Esc Anna Nery Rev Enferm. 2020;24:e20190113.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global Cancer Observatory. 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: https://www.gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/39-all-cancers-fact-sheet.pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Mar 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and death in 29 cancer groups in 2017 and trend analysis from 1990 to 2017 from the global burden of disease study. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unplanned hospitalizations in older patients with cancer: Occurrence and predictive factors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;12:368-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of witnessing death on hospice patients. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1785-94.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Death anxiety, perceived social support, and demographic correlates of patients with breast cancer in Pakistan. Death Stud. 2020;44:787-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fear of dependency as a predictor of depression in older adults. Innov Aging. 2017;1(Suppl 1):132.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches United States: SAGE Publications; 2017.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. 2012. Resolução. No. 466 Available from: http://www.bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2013/res0466_12_12_2012.html [Last accessed on 2019 Aug 21]

- [Google Scholar]

- The perception of the nursing professionals during the ritual of prepare of the bodies. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 1998;32:117-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desensitizing effect of frequently witnessing death in an occupation: A study with Turkish health-care professionals. Omega (Westport) 2020:1-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nursing professionals' attitudes, strategies, and care practices towards death: A systematic review of qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52:301-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathways for a 'Good Death': Understanding end-of-life practices through an ethnographic study in two Portuguese palliative care units. Sociol Res Online 2020:1-17.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of severe depressive symptoms increases as death approaches and is associated with disease burden, tangible social support, and high self-perceived burden to others. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:83-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A good death from the perspective of palliative cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:933-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient's perspectives on the notion of a good death: A systematic review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59:152-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]