Translate this page into:

Development of a model of Home-based Cancer Palliative Care Services in Mumbai - Analysis of Real-world Research Data over 5 Years

*Corresponding author: Mary Ann Muckaden, Department of Palliative Medicine, Tata Memorial Hospital, Homi Bhaba National Institute, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. muckadenma@tmc.gov.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Dhiliwal SR, Ghoshal A, Dighe MP, Damani A, Deodhar J, Chandorkar S, et al. Development of a model of Home-based Cancer Palliative Care Services in Mumbai - Analysis of Real-world Research Data over 5 Years. Indian J Palliat Care 2022;28:360-90.

Abstract

Objectives:

Patients needing palliative care prefer to be cared for in the comfort of their homes. Although private home health-care services are entering the health-care ecosystem in India, for the majority it is still institution-based. Here, we describe a model of home-based palliative care developed by the Tata Memorial Hospital, a government tertiary care cancer hospital.

Materials and Methods:

Data on patient demographics, services provided and outcomes were collected prospectively for patients for the year November 2013 - October 2019. In the 1st year, local general physicians were trained in palliative care principles, bereavement services and out of hours telephone support were provided. In the 2nd year, data from 1st year were analysed and discussed among the study investigators to introduce changes. In the 3rd year, the updated patient assessment forms were implemented in practice. In the 4th year, the symptom management protocol was implemented. In the 5th and 6th year, updated process of patient assessment data and symptom management protocol was implemented as a complete model of care.

Results:

During the 6 years, 250 patients were recruited, all suffering from advanced cancer. Home care led to good symptom control, improvement of quality of life for patients and increased satisfaction of caregivers during the care process and into bereavement.

Conclusion:

A home-based model of care spared patients from unnecessary hospital visits and was successful in providing client centred care. A multidisciplinary team composition allowed for holistic care and can serve as a model for building palliative care capacity in low- and middle-income countries.

Keywords

Palliative care

Cancer

Home care

Program development

Hospice care

INTRODUCTION

Over the past five decades, palliative care has evolved from a philosophy of care that focuses on the past days of life to a professional specialty that delivers comprehensive supportive care to patients with advanced illnesses throughout the disease trajectory. Conceptualised by Dame Cicely Saunders in the 1960s, the first model of care was community-based hospice care.[1] In the 1970s, Balfour Mount coined the term palliative care and started the first palliative care unit in an acute care academic hospital in Montreal.[2] This model of inpatient care was widely accepted and contributed to a rapid growth in inpatient palliative care teams worldwide. In the 1990s, several palliative care teams started to see patients in outpatient clinics which paved the way for patients to gain access to palliative care earlier in the disease trajectory.[3] The model of palliative care continues to evolve to better serve a growing number of patients throughout the disease continuum while adapting to an aging population and the ever-changing landscape of novel cancer therapeutics.

At present, the five major service delivery models of palliative care are seen in India. These are outpatient palliative care clinics, inpatient palliative care consultation teams, acute palliative care units, community-based palliative care and hospice care.[4] In 2020, the World Palliative Care Alliance released a global atlas to assess the provision of palliative care, which reported that only 14% of those in need are receiving palliative care worldwide and 78% of the unmet need was in Low- or Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). In India, there are an estimated 6 million people per year in need of palliative care.[5] As the burden of chronic illness rises in these countries, the gaps in palliative care will continue to rise unless efforts are made to expand access to palliative care services.

In this paper, we describe a model for home-based palliative care that has been developed by the Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH), a tertiary cancer care centre, to serve patients in and around Mumbai, India since 1997. On an average TMH cares for more than 3000 patients in home care annually, but we have reported about the 250 patients in this paper which participated in this research project.[6] By analysing and presenting the model of care provided by us, we hope to raise awareness of the need for palliative care in LMICs and to highlight the potential of home-based palliative care model. This study was designed to develop a model of comprehensive home-based palliative care in Mumbai, with active liaison of the local General Practitioner for out of hours care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population and setting

Mumbai based patients registered in TMH; Palliative Care Services were screened for the study. For those residing within Mumbai metropolitan region and agreed to take part in the study, informed consents were taken prior to the recruitment in the study. Participants with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) -04 and physician predicted survival <4 weeks and patients who have agreed for the homecare service and later migrated to territory beyond homecare were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (TMH IRB project 920).

Home care team composition and working pattern

Our home care teams operated out of Parel, which is in the central part of Mumbai. All the referrals were made from the hospital based Palliative Care Unit. Two home care teams took part in this project. Each team was composed of a physician, nurse and medical social worker, all trained in palliative care. Each of the two teams covers the urban and suburban area of Mumbai [Figure 1]. Home care teams made an average of six visits per day during the study period. During the first home visit, the patient’s history is taken and medical, nursing and psychosocial needs are reviewed. And addressed at that visit, with in-depth counselling typically reserved for subsequent visits. Based on symptoms at presentation and state of disease, patients are triaged to be high need (seen weekly), medium need (seen every 15 days), or low need (seen once monthly). With changes in symptoms and disease progression, the frequency of home visits can change and sometimes patients may be seen up to 2–3 times per week if needed. During home visits, caregivers were taught to provide nursing care, such as wound care and procedures, such as insertion of nasogastric tubes or Foley catheters, were managed by the nurses. In addition, procedures such as paracentesis were done at home if the patient was unable to go to the hospital. The home care team would liaison with the patient’s family physician to coordinate care, which became especially important during out of office hours. Medications are prescribed as seemed necessary. Patients are given an emergency phone line where they can reach a physician or nurse at any time. The most common reasons for calls were worsening pain, intractable vomiting and delirium. Families are often given additional prescriptions of medications in anticipation of symptom recurrence. If the issue cannot be managed over the phone, the team will either visit the patient that day or refer the patient to the hospital for calls made at night or on weekends. Rarely, the patient is immediately referred to the hospital (e.g., concern for neutropenic fever). The service also takes a note of the psychosocial well-being of the caregivers, ways to involve the larger community for patient care, to get over the fear of contagion of cancer and social stigma. Counselling helped in better coping of families and avoided unnecessary intensive therapies. Discussion about care plan, end of life symptoms and process of dying helped in preparation of the patients and families.[7]

- Model of palliative care and the geographical extent of the home-based palliative care.

Intervention

1st year: Preliminary Assessment Form (symptom severity was assessed with the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, patients were evaluated with ECOG Performance Scale, Psychosocial Assessment was done by a trained medical social worker, which gathered information about spiritual, social and emotional issues, in addition to patient awareness about their illness), Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project (CANHELP) Patient Questionnaire and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care (QLQ-C15-PAL) were filled and standard palliative care procedure were followed, including home-based care (if agreed) based on triaging “High-01,” “medium-02,” and “low-03” priority. Local general physicians (LGPs) were trained and contacted if necessary. Bereavement services were provided after the patient deceased and CANHELP Bereavement questionnaire were filled. Out of hours Care was facilitated over telephone with the help of trained LGPs. (See Appendix for the tools used)

2nd year: The data from 1st year were analysed and discussed with study investigators and peer reviewed by external experts. Changes were introduced in the process of patient assessment and documentation:

3rd year: With the updated patient assessment forms, routine Home Care was continued and recorded.

4th year: Initiation of implementation of updated process of patient assessment data and symptom management protocol.

5th and 6th year: Updated process of patient assessment data and symptom management protocol was implemented as a complete model.

Statistical analysis

The number of patients to be recruited was based on real-world data on patient recruitment from homecare services and no formal sample size was calculated as there was no previous data on the effectiveness on such intervention. Descriptive statistics was used for summarisation of demographics, clinical and home care data. Comparison of data was made before and after intervention. All analyses were done with SPSS software and a P < 0.05 was considered as significant.[8] The data were stored securely and unanimously by the project investigators in accordance with institutional data protection policies.

RESULTS

For this research project, we screened 500 participants and recruited 250 over a period of 6 years (November 2013 - October 2019). Baseline characteristics are summarised in [Table 1]. The median age was 57 years (range 18–92 years), 168 (67.02%) were women and 138 (55.2%) had monthly income below ₹5,000. Two hundred eight (83.2%) patients were married being cared for by their spouse. Head and neck cancers were present in 57 (22.8%) patients, followed by Genito-urinary cancers in 54 (21.6%) and overall, 221 (88.4%) people were suffering from stage IV cancer.

| Gender distribution | Numbers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 82 | 32.8 |

| Female | 168 | 67.2 |

| Family income (₹) | ||

| below 5000 | 138 | 55.2 |

| 5001–10,000 | 56 | 22.4 |

| 10001–20,000 | 33 | 13.2 |

| 20001–30,000 | 14 | 5.6 |

| 30001–40,000 | 5 | 2 |

| 40001–50,000 | 3 | 1.2 |

| above 50,001 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 85 | 34 |

| Secondary | 89 | 35.6 |

| higher secondary | 37 | 14.8 |

| graduation and above | 39 | 15.6 |

| Age distribution | ||

| below 20 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 21–40 | 34 | 13.6 |

| 41–60 | 115 | 46 |

| 61–80 | 92 | 36.8 |

| above 80 | 8 | 3.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 208 | 83.2 |

| Unmarried | 13 | 5.2 |

| Widower | 3 | 1.2 |

| Widow | 25 | 10 |

| Separated | 1 | 0.4 |

| Site of primary cancer | ||

| Bone and Soft tissue | 10 | 4 |

| Breast | 36 | 14.4 |

| Carcinoma of unknown primary | 1 | 0.4 |

| Gastrointestinal | 14 | 5.6 |

| Genito-urinary | 54 | 21.6 |

| Head and neck | 57 | 22.8 |

| Haematological and lymphoid | 15 | 6 |

| Hepato-biliary | 17 | 6.8 |

| Lung | 35 | 14 |

| PNET | 11 | 4.4 |

| Stage of cancer | ||

| Stage III | 14 | 5.6 |

| Stage IV | 221 | 88.4 |

| Others (Haematological cancers) | 15 | 6 |

| Treatment received | ||

| Multimodality | 134 | 53.6 |

| Chemotherapy | 61 | 24.4 |

| None | 32 | 12.8 |

| Radiotherapy | 13 | 5.2 |

| Surgery | 10 | 4.0 |

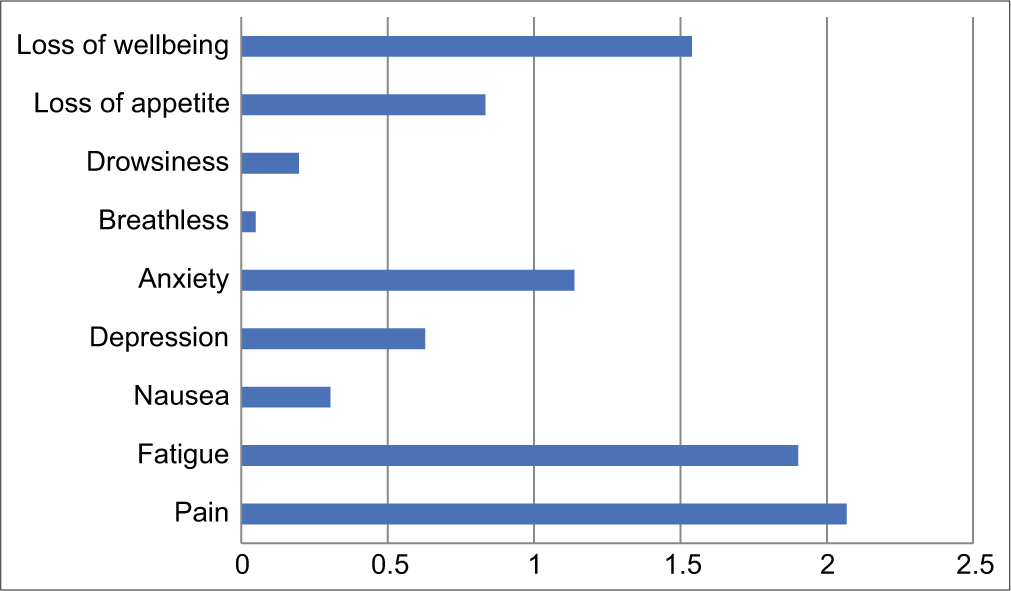

1st year - 102 participants were recruited and the most common symptom at initial referral was pain, followed by fatigue and loss of well-being [Figure 2]. Out of 102 patients, 98 patients had support from family physicians, four patients were visiting nearby hospital whenever in need. Of 98 family physicians who cared for the patients, 53 attended palliative care training programs. This itself was a benefit of this project. Seventy-six patients required intervention from family physician during this period. The most common reason to contact family physician was pain, generalised weakness, constipation, cough and breathlessness. Others were in liaison, with family physician but did not require any intervention except for death certificate. Only four patients (6%) were hospitalised during the 2013–2014 years for management of difficult symptom such as uncontrolled pain, breathlessness and delirium; only 17 (16.7%) needed referral to hospice. About 67.65% (n = 69) patients/caregivers-maintained medicine book and were compliant with home care interventions. Apart from regular home visits, the patients were also on telephonic follow-up, every patient received minimum of one call in 10 days from the home care team. The total number of calls done by the home care team for the patient follow-up was 778 for 1st year (7.62 telephonic calls to every patient on an average). There was progressive improvement in the QLQ-C15-PAL of the patient between home-based care visits, for physical function (P = 0.038), overall quality of life (P = 0.004), appetite (P < 0.001), fatigue (P = 0.001), nausea (P < 0.001) and dyspnoea (P = 0.005) [Figure 3].

- The edmonton symptom assessment system average score (n=102).

- European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ–C15–PAL data.

We assessed patient satisfaction using CANHELP patient questionnaire which showed that-76.92% were very satisfied, 14.10% were extremely satisfied and 8.97% were somewhat satisfied with care provided for illness management; 66.23% were very satisfied, 25.97% were extremely satisfied and 7.79% were somewhat satisfied with the communication aspect of care; 59.09% were very satisfied, 28.24% were extremely satisfied and 12.66% were somewhat satisfied with the aspect of care related to the decision-making; 66.63% were very satisfied, 27.27% were extremely satisfied, 9.09% were somewhat satisfied and 0.38% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to “relationship with the doctors;” 62.33% were very satisfied, 16.88% were extremely satisfied, 19.48% were somewhat satisfied and 0.54% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to role of the family members; and 66.62% were very satisfied, 23.07% were extremely satisfied and 12.98% were somewhat satisfied with the aspect of care related to the well-being of the patient.

Assessment of Caregiver Satisfaction through CANHELP Caregiver Questionnaire showed that – 61.21% were very satisfied, 15.21% were extremely satisfied, 10.28% were somewhat satisfied and 0.40% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the communication and decision making; 73.62% were very satisfied, 15.95% were extremely satisfied, 10.14% were somewhat satisfied and 0.31% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the illness management; 77.35% were very satisfied, 12.98 % were extremely satisfied and 9.65% were somewhat satisfied with the aspect of care related to characteristics of doctors and nurses; 61.22% were very satisfied, 18.24% were extremely satisfied, 17.37% were somewhat satisfied and 0.71% was not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the involvement of caregiver; 66.09% were very satisfied, 20.55% were extremely satisfied, 12.67% were somewhat satisfied and 0.63% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the wellbeing of the caregiver; and 65.51% were very satisfied, 21.26% were extremely satisfied, 13.21% were somewhat satisfied and 0.86% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the relationship with the doctors [Figure 4].

- Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project data.

Among 102 patients, 68 patients died in first year of study – 41 (60.29%) at home, 17 (25%) at hospice and 10 (14.7%) at hospital inpatient unit. The families of the deceased patients received a bereavement visit by the team. The initial bereavement visit is typically scheduled after mourning rituals are complete (for Hindu patients, 13 days after death, for other religions ~10 days). Subsequent visits or calls were made if there appeared to be a need for ongoing support, such as those who lost a child or spouse. In these circumstances, bereavement counselling was typically provided up to 6 months, or occasionally longer, depending on need. Caregiver satisfaction was assessed with a post-bereavement questionnaire that is administered 6–12 weeks after a patient’s death. Feedback is provided by 70–75% of those who receive bereavement visits or calls. The satisfaction rate in 2009–2010 was 90%. If any caregivers report that they are not satisfied with care, the team tries to assess the reason why. The responses with CANHELP Caregiver Questionnaire were - 68.01% were very satisfied, 24.06% were extremely satisfied, 06.78% were somewhat satisfied and 1.15% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the relationship with the doctors; 81.56% were very satisfied, 14.74% were extremely satisfied and 3.70% were somewhat satisfied with the aspect of care related to doctors and nurses; 75.47% were very satisfied, 18.68% were extremely satisfied, 04.87% were somewhat satisfied and 0.98% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the illness management; 65.34% were very satisfied, 17.28% were extremely satisfied, 15.28% were somewhat satisfied and 2.10% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to communication and decision making; 63.34% were very satisfied, 21.62% were extremely satisfied, 12.37% were somewhat satisfied and 2.67% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the involvement of caregiver; and 68.12% were very satisfied, 22.79% were extremely satisfied, 08.57% were somewhat satisfied and 0.52% were not very satisfied with the aspect of care related to the well-being of the caregiver.

Funding for services came from individual donations and grants from trusts, foundations, private companies and units in the public sector through the hospital. The total average cost per patient was Rs. 9,000–10,000. The breakdown of cost is: 70% salaries, 20% transport, 10% centre operational costs and miscellaneous. All services were free of charge for patients. Medicines are obtained by the patients from the hospital through different financial system and have a subsidised billing system be clear.

2nd year - The data from 1st year were analysed and discussed with study investigators. Changes were introduced in the process of patient assessment and documentation:

- Detailed assessment of symptoms

- Adding Distress Thermometer

- Adding FACES scale and body diagram

- Adding detailed systematic evaluation

- Adding comprehensive care plan in management.

3rd year - The updated patient assessment forms were implemented in practice among 148 participants.

4th year - Initiation of implementation and development of a symptom management protocol for Home Care Services in Mumbai (India) (see Appendix).

5th year - Updated process of patient assessment data and symptom management protocol was implemented as a complete model (see Appendix).

DISCUSSION

There has recently been on focus on the importance of integrating palliative care into health care systems, with a 2020 publication defining the gaps between need and access.[4] Although the first palliative care centres in India were established in the late 1980s, there has been little progress to expand the delivery of palliative care to most of the country.[9] Here, we discuss the various models of palliative care services as applicable to our service, with focus on the development of Home Care model in Mumbai.

Outpatient palliative care clinics

Compared with the other service models, outpatient palliative care clinics require relatively few resources, can serve many patients and represent the main setting for patients to be seen early along the disease trajectory.[10] In a 2020 national survey, 68.1% of National Cancer Grid designated cancer centres offered outpatient palliative care.[4] Several variations of outpatient palliative care interventions exist, including stand-alone clinics, embedded clinics, telehealth-based palliative care and enhanced primary palliative care.[11] The TMH has one of the largest cancer care programs in India. The number of patients referred to the outpatient clinic increased steadily from 750 in 2010 to 5000 in 2020.[6] Much heterogeneity exists in the referral criteria for outpatient clinics. Although clinical trials support universal referral based on time since diagnosis or prognosis, the current palliative care workforce may not be able to serve all patients with cancer, particularly when more patients are being seen earlier in the disease trajectory.

Telehealth interventions

Telehealth interventions may be the primary model of outpatient palliative care delivery, particularly for patients in areas where access to tertiary care is more challenging or in cases of challenging times like COVID-19. In the Project Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends II study, Bakitas et al. compared patients randomly assigned to a nurse-led, predominantly telehealth-based palliative care intervention and usual care. The structured palliative care intervention was found to improve quality of life and mood but not symptom burden or quality of end-of-life care.[12] Telehealth palliative care also may be provided as an outreach to augment existing outpatient clinics. Specifically, clinicians may be able to provide education, counselling and symptom monitoring in a cost-effective manner with the potential to improve adherence, increase hospice referrals and minimise acute care visits.

Inpatient consultation services

Inpatient consultation teams represent the backbone of palliative care and often complement outpatients and home-based palliative care services by seamless transition of patient referral process. In India, 66.3% of NCG-designated cancer centres reported having inpatient consultation teams.[4] Palliative care consultants, including physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses and/or psychosocial professionals, typically have daily rounds with hospitalised patients. At this time, the existing palliative care infrastructure cannot accommodate universal referral of all hospitalised patients with advanced cancer. The literature has outlined several criteria for referral of patients to inpatient palliative care.[13-15] Continuity of care after discharge can be provided by outpatient palliative care and/or home-based palliative care [Figure 1].

Home-based palliative care

Home-based palliative care programs provide in-person visits, equipment, supplies and telephone support for patients at home or in community-based care facilities, such as nursing home and skilled nursing facilities. Only approximately 25% of cancer centres operate community-based palliative care teams and other centres may contract palliative care services in the community.[4] Patients enrolled in such programs typically are clinically stable and have a poor performance status, short, expected survival and a desire to continue care at ambulatory clinics [Figure 1]. Meta analyses found that home-based palliative care significantly increases the rate of home death.[16,17] These programs often are attached to an inpatient unit. In recent years, home-based care has been increasingly pursued as an opportunity for health care expansion in India and is a model that is well-suited for the delivery of palliative care. When terminally ill patients require on-going management of pain and other symptoms, but do not have acute care needs requiring hospitalisation, home care allows them to remain comfortable while reducing the burden of care on the family.

A survey of patients in Pune found that 83% of respondents would prefer to die at home rather than in a hospital or care facility.[18] In addition, this study as well as in others have shown that home care decreases the number of hospital visits and deaths that occur in the hospital, potentially saving families, especially those in rural areas, significant time and money. Home care saves patients and their families the cost and time of travel to and from the hospital or clinic and eliminates the costs of an acute hospital stay. Home-based end-of-life care appeared efficacious when there was provision for nursing care, or family support. Most of our home care patients are lower or middle class and socio-economic rehabilitation is one of their priorities. Staffs are available by phone for caregivers and patients, allowing for questions to be answered and medical issues to be triaged remotely. Getting evidenced based medical care at home at subsidised cost is commendable in the current economic scenario of Indian healthcare. The TMH is a grant in aid institution under the Government of India, but the home care program runs on charity funded by various NGOs. Despite such financial uncertainty, the home-based palliative care services could achieve results comparable to a 2015 systematic review.[19]

Being a family caregiver to a patient nearing the end of their life is a challenging and confronting experience. Studies show that caregiving can have negative consequences on the health of family caregivers including fatigue, sleep problems, depression, anxiety and burnout. One of the benefits of palliative care at home is to provide psychosocial support to patients and families facing terminal illness.[20]

Seen as a “beacon of hope,” the palliative care model in the state of Kerala stands in stark contrast to the state of palliative service delivery within the rest of India. Formed through the collaboration of 4 NGOs in 1999, the Neighbourhood Network in Palliative Care extends throughout most of the state and is rooted in the notion of community involvement. At the heart of this delivery has been a workforce primarily comprised community volunteers, who are engaged in all aspects of palliative care units within the state.[21] Unlike in Kerala, our model complements an institution-based cancer care by providing a model of home-based palliative care in which trained specialised staff delivers services rather than community volunteers. Many organisations have preferred this contrast by raising concerns about the quality of care delivered by community volunteers versus trained home care teams comprised doctors, nurses and counsellors. At present, other delivery models in India seem to have adopted a similar hybrid approach to home based palliative care. Guwahati Pain and Palliative Care Society in Assam, operates through a combination of clinical staff and community volunteers, CanSupport in Delhi fosters continuity between outpatient and home-based care, while PALCARE provide home-based, multidisciplinary, palliative care service for patients, primarily those in stage 3/stage 4 cancer, across the length and breadth of Greater Mumbai.[22,23]

As palliative care development continues in LMICs, the challenges that home care services have faced can serve as valuable lessons. One such area is to improve communication and information exchange with cancer centres and oncologists. An on-going challenge is to educate physicians about the role of palliative care and how they can identify patients who would benefit from referral. In addition, due to the lack of government and private funding, the inconsistent source of funding from year to year remains a concern. Finally, as the service expands and adapts to serve more patients, more physicians and nurses will be needed who are willing to be trained in palliative care and who have experience with prescribing opiates.

CONCLUSION

Home-based palliative care can help in good symptom control of patients suffering from advanced cancer and can result in satisfaction of the caregivers throughout and in bereavement. The Department of Palliative Medicine at the TMH, over the course of two and half decades, has developed a sustainable model for delivering home-based end of life care in Mumbai. Its team-based approach allows for the coordination of care to a growing number of patients and families. Although we can serve only a fraction of the country’s population in need, its on-going success highlights the impact that quality, convenient and public/charity funded palliative care can have in the developing world.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the administration of TMH for their support, EMPATHY foundation and numerous other funders/donors for helping in times of need. We would also like to acknowledge Dr Naveen Salins, Dr Reena George, Dr Anil Kumar Paleri, Dr Gayatri Palat and Ms. Harmala Gupta for their valuable contribution in this project. The symptom management protocol has been adapted from PALCARE’s Palliative Care Guidelines for a Home Setting in India, developed by a committee of palliative care specialists, on behalf of The Jimmy S Bilimoria Foundation and available on https://guidelines.palcareindia.com

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Arunangshu Ghoshal and Jayita Deodhar are members of editorial board of IJPC.

References

- The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital; the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;115:119-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrated outpatient palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2019;33:123-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provision of palliative care in National Cancer Grid treatment centres in India: a cross-sectional gap analysis survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHPCA, Global Atlas of Palliative Care. 2020. (2nd ed). Geneva: World Health Organization; Avaialble from: http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 02]

- [Google Scholar]

- TMC-Annual Report-tata Memorial Centre. Available from: https://www.tmc.gov.in/index.php/en/tmc-annual-report [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 04]

- [Google Scholar]

- Respite model of palliative care for advanced cancer in India: Development and evaluation of effectiveness. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;5:1-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21 United States: International Business Machines Corporation; 2020.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospice and palliative care development in India: A multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:583-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Models of outpatient palliative care clinics for patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:187-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative cancer care in the outpatient setting: Which model works best? Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302:741-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Referral patterns and proximity to palliative care inpatient services by level of socio-economic disadvantage. A national study using spatial analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:1-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of reasons for referral and activities of hospital palliative care teams using a standard format: A multicenter 1000 case description. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:579-87.e6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timing of referral to inpatient palliative care services for advanced cancer patients and earlier referral predictors in mainland China. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14:503-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors predicting a home death among home palliative care recipients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8210.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:23-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preference of the place of death among people of Pune. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20:101-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review of the evidence on home care reablement services. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30:741-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for family carers of palliative care patients. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbourhood network in palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2005;11:6-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cansupport: A model for home-based palliative care delivery in India. Ann Palliat Med. 2016;5:166-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Who we are. 2019. Plant Eng. 73:36-7. Available from: https://www.palcareindia.com/about/who-we-are [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 05]

- [Google Scholar]

APPENDIX

I) Preliminary Assessment Form

TATA MEMORIAL CENTRE

TATA MEMORIAL HOSPITAL

SECTION 6: MANAGEMENT PLAN

6.1 GOALS OF CARE

6.2 PHARMACOLOGICAL

6.3 NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL

6.3.1 Psychosocial

Counseling

Social Worker referral for: Change of category/Temporary accommodation/Travel concession/Ration coupon/Help for education or employment/Support group/Financial support/Ref to V Care

6.3.2 Rehabilitation services

6.3.3 Nutrition clinic

6.3.4 Interventions/procedures

6.3.6 ANY OTHER

II) Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)

III) CANHELP Patient Questionnaire

Study ID: ____________

For each of the questions, please tell us first HOW IMPORTANT that statement is in relation to your care. Then tell us HOW SATISIFIED you are right now with that aspect of care.

Issue #

Importance

1. Not at all important

2. Not very important

3. Somewhat important

4. Very important

5. Extremely important

Satisfaction

1. Not at all satisfied

2. Not very satisfied

3. Somewhat satisfied

4. Very satisfied

5. Completely satisfied

1. The quality of care you received.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

2. You knew the doctor(s) in charge of your relatives care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

3. Your doctor takes a personal interest in you and your medical problems.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4. Your doctor is available when you need him or her.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

5. You have trust and confidence in the doctors responsible for your care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

6. You have trust and confidence in the nurses responsible for your care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

7. The doctors and nurses looking after you know enough about your health problems to give you the best possible care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

8. The doctors and nurses looking after you are compassionate and supportive.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

9. You are treated by those doctors and nurses in a manner that preserves your sense of dignity.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

10. You receive timely and thorough tests and treatments for your health problems.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

11. Your physical symptoms such as pain, shortness of breath, and nausea are relieved.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

12. Your emotional problems such as depression and anxiety are relieved.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

13. Someone is available to help you with your personal care such as bathing, toileting, dressing and eating when needed.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

14. You receive good care when a family member or friend is not able to be with you.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

15. There are services available to look after your health care needs at home.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

16. Health care workers work together as a team to look after you.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

17. You are able to manage the financial costs associated with your illness.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

18. The environment or surroundings in which you are cared for is calm and restful.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

19. The care and treatment you receive is consistent with your wishes.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

20. The doctors explain things in relating to your illness in a straightforward, honest manner.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

21. The doctors explain things relating to your illness in a way you can understand.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

22. You receive consistent information about your condition from all doctors and nurses looking after you.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

23. The doctors listen to what you have to say.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

24. You receive updates about your condition, treatments, test results, etc. in a timely manner.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

25. You discuss options with your doctor(s) about where you would be cared for (in hospital, at home, or elsewhere) if you were to get worse.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

26. You discuss options with your doctor(s) about the use of life sustaining technologies (for example: CPR or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, breathing machines, dialysis).

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

27. You come to understand what to expect in the end stage of your illness (for example, in terms of symptoms and comfort measures).

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

28. You participate in decisions made regarding your medical care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

29. You feel confident in the ability of a family member or friend to help you manage your illness at home.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

30. You discuss your wishes for future care with your family member (someone who would make decisions for you) in the event you become unable to make those decisions yourself.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

31. You are comfortable talking about your illness, dying and death with the people you care about.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

32. Your relationships with family and others you are care about are strengthened.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

33. You are not a burden on your family or others you care about.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

34. You have family or friends to support you when you feel lonely or isolated.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

35. You feel confident in your own ability to manage your illness at home.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

36. You are able to contribute to others in a meaningful way.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

37. You do the special things you want to do while you are able (for example: resolve conflicts, complete projects, participate in special family events, travel).

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

38. You are at peace.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

IV) CANHELP Family Questionnaire

Study ID: ____________

For each of the questions, please tell us first HOW IMPORTANT that statement is in relation to your care. Then tell us HOW SATISIFIED you are right now with that aspect of care.

Issue #

Importance

1. Not at all important

2. Not very important

3. Somewhat important

4. Very important

5. Extremely important

Satisfaction

1. Not at all satisfied

2. Not very satisfied

3. Somewhat satisfied

4. Very satisfied

5. Completely satisfied

1. In general, how satisfied are you with the quality of care your relative received during the past month.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

2. In general, how satisfied are you with the way you were treated by the doctors and nurses looking after your relative during the past month?

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

3. You knew the doctor(s) in charge of your relatives care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4. The doctor(s) took a personal interest in your relative.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

5. The doctor(s) were available when you or your relative needed them (by phone or in person).

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

6. You have trust and confidence in the doctors responsible for your relatives care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

7. You had trust and confidence in the nurses responsible for your relatives care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

8. The doctors and nurses looking after your relative know enough about their health problems to give them the best possible care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

9. The doctors and nurses looking after your relative are compassionate and supportive of him or her.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

10. The doctors and nurses looking after your relative are compassionate and supportive of you.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

11. Your relative was treated by those doctors and nurses in a manner that preserved his or her sense of dignity.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

12. The tests that were done and the treatments that were given for your relatives medical problems.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

13. The physical symptoms such as pain, shortness of breath, and nausea were adequately assessed and controlled.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

14. The emotional problems your relative had, such as depression and anxiety, were adequately assessed and controlled.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

15. The help your relative received with personal care such as bathing, toileting, dressing and eating when needed.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

16. Your relative received good care when you were not able to be with him/her.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

17. The home care services your relative received.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

18. The healthcare workers worked together as a team to look after your relative.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

19. You are able to manage the financial costs associated with your relative’s illness.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

20. With the environment or surroundings that your relative was cared for in.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

21. The care and treatment your relative received was consistent with his or her wishes.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

22. The doctor(s) explained things in relating to your relatives illness in a straightforward, honest manner.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

23. The doctors explain things relating to your relative’s illness in a way you understand.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

24. You receive consistent information about your relative’s condition from all the doctors and nurses looking after him/her.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

25. You receive updates about your relatives condition, treatments, test results, etc. in a timely manner.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

26. The doctor(s) listened to what you had to say.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

27. Your discussions with the doctor(s) about where your relative would be cared for (in hospital,at home, or elsewhere) if he or she were to get worse.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

28. The level of confidence you felt in your ability to help your relative manage his or her illness.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

29. Your discussions with the doctor(s) about the use of life sustaining technologies (for example: CPR or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, breathing machines, dialysis).

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

30. You have come to understand what to expect in the end stage of your relatives illness (for example, in terms of symptoms and comfort measures).

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

31. Your role in decision-making regarding your relative’s medical care.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

.32. The discussions with your relative about wishes for future care in the event he or she is unable to make those decisions.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

33. You were able to talk comfortably with your relative about his or her illness, dying, and death.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

34. Your relationship with your relative was strengthened.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

35. The level of confidence you felt in your relative’s ability to manage his or her own illness.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

36. You had enough time and energy to take care of yourself.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

37. You had family or friends to support you when you felt lonely or isolated.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

38. You were able to contribute to others in a meaningful way.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

39. You and your relative did the special things you want to do (for example: resolve conflicts, complete projects, participate in special family events, travel.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

40. You were at peace.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. N/A. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

V) CANHELP Bereavement questionnaire

1.A Where did your relative die?

Hospital Ward Intensive Care Unit Palliative Care Unit Home or Retirement Home (or family member home) .

Long Term/Chronic Care Facility . Other (name) __________________________

2.A In your opinion, was this your relative’s preferred location of death? .

Yes . No

If No, where would your relative have preferred to die?

Hospital Ward Intensive Care Unit Palliative Care Unit Home or Retirement Home (or family member home) .

Long Term/Chronic Care Facility . Other (name) __________________________

3.A Was this your preferred location for your relative’s death? .

Yes . No

If No, where would you have preferred your relative to die?

Hospital Ward Intensive Care Unit Palliative Care Unit Home or Retirement Home (or family member home) .

Long Term/Chronic Care Facility . Other (name) __________________________

The following questions concern the care your relative received in the last month of his or her life. For each one, please indicate the degree to which you are satisfied.

1.Not At All 2.Not Very 3.Somewhat 4.Very 5.Completely

1. In general, how satisfied are you with the quality of care your relative received in the last month of life?

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

2. In general, how satisfied are you with the way you were treated by the doctors and nurses looking after your relative in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Relationship with the Doctors

3. How satisfied are you that you knew the doctor(s) in charge of your relative’s care in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4. How satisfied are you that the doctor(s) took a personal interest in your relative in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

5. How satisfied are you that the doctor(s) were available when you or your relative needed them (by phone or in person) in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

6. How satisfied are you with the level of trust and confidence you had in the doctor(s) who looked after your relative in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Characteristics of the Doctors and Nurses

7. How satisfied are you with the level of trust and confidence you had in the nurses who looked after your relative in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

8. How satisfied are you that the doctors and nurses who looked after your relative in the last month of life knew enough about his or her health problems to give the best possible care? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

9. How satisfied are you that the doctors and nurses looking after your relative in the last month of life were compassionate and supportive of him or her? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

10. How satisfied are you that the doctors and nurses looking after your relative in the last month of life were compassionate and supportive of you? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

11. How satisfied are you that the doctors and nurses who treated your relative in the last month of life preserved his or her sense of dignity? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Illness Management

12. How satisfied are you with the tests that were done and the treatments that were given for your relative’s medical problems in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

13. How satisfied are you that physical symptoms (for example: pain, shortness of breath, nausea) your relative had in the last month of life were adequately assessed and controlled? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

14. How satisfied are you that emotional problems (for example: depression, anxiety) your relative had in the last month of life were adequately controlled? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

15. How satisfied are you with the help your relative received with personal care in the last month of life (for example: bathing, toileting, dressing, eating)? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

16. How satisfied are you that, in the last month of life, your relative received good care when you were not able to be with him/ her? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

17. How satisfied are you with home care services your relative received in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

18. How satisfied are you that health care workers worked together as a team to look after your relative in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

19. How satisfied are you that you were able to manage the financial costs associated with your relative’s illness in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

20. How satisfied are you with the environment or the surroundings where your relative was cared for in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

21. How satisfied are you that the care and treatment your relative received in the last month of life was consistent with his or her wishes? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and Decision Making

22. How satisfied are you that the doctor(s) explained things to you relating to your relative’s illness in the last month of life in an honest manner? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

23. How satisfied are you that the doctor(s) explained things to you relating to your relative’s illness in the last month of life in a way you could understand? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

24. How satisfied are you that you received consistent information about your relative’s condition from all the doctors and nurses looking after him or her in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

25. How satisfied are you that you received updates about your relative’s condition, treatments, test results, etc. in a timely manner in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5

26. How satisfied are you that the doctor(s) listened to what you had to say in the last month of your relative’s life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

27. How satisfied are you with discussions in the last month of life with the doctor(s) about where your relative would be cared for (in hospital, at home, or elsewhere)? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Your Involvement 28. How satisfied are you with the level of confidence you felt in your ability to help your relative manage his/her illness in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

29. How satisfied are you with discussions in the last month of your relative’s life with the doctor(s) about the use of life sustaining technologies (for example: CPR or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, breathing machines, dialysis)? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

30. How satisfied are you that you came to understand what to expect in the last month of your relative’s life (for example: in terms of symptoms and comfort measures)? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

31. How satisfied are you with your role in decision-making regarding your relative’s medical care in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

32. How satisfied are you with discussions with your relative, while he or she was able, about preferences for care and treatment at the end of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

33. How satisfied are you that you were able to talk comfortably with your relative, while he or she was able, about dying and death? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

34. How satisfied are you that your relationship with your relative was strengthened in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Your Well Being

35. How satisfied are you with the level of confidence you felt in your relative’s ability to manage his/her own illness in the last month of life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

36. How satisfied are you that in the last month of your relative’s life you had enough time and energy to take care of yourself? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

37. How satisfied are you that you had family or friends to support you when you felt lonely or isolated in the last month of your relative’s life? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

38. How satisfied are you that you were able in the last month of your relative’s life to contribute to others in a meaningful way? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

39. How satisfied are you that you and your relative did special things you wanted to do while your relative was able (for example: resolve conflicts, complete projects, participate in special family events, travel)? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

40. How satisfied are you that you were at peace in the last month of your relative’s life?

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Thank you for helping us to understand how to provide better care in future for patients like your relative.

VI) EORTC QLQ – C15 – PAL

VII) Symptom management guidelines

The symptom management protocol has been adapted from PALCARE’s Palliative Care Guidelines for a Home Setting in India, developed by a committee of palliative care specialists, on behalf of The Jimmy S Bilimoria Foundation, and available on https://guidelines.palcareindia.com/