Translate this page into:

Exploring Organizational Culture Regarding Provision and Utilization of Palliative Care in a Nigerian Context: An Interpretive Descriptive Study

Address for correspondence: Dr. David A Agom, Department of Health and Social Science, London School of Science and Technology – Luton Campus, 4 Dunstable Rd., Luton LU1 1DX, UK. E-mail: davidagom56@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Palliative care (PC) continues to be underutilized in Nigeria, but there is a lack of studies that explore organizational cultural dynamics regarding PC in Nigeria. The study aimed to understand the organizational culture in order to identify organizational enablers and inhibitors of the provision and utilization of PC in a Nigerian context.

Methods:

Identification of the organizational culture was developed using a qualitative interpretive descriptive design. Cultural enablers and inhibitors were mapped out using semi-structured interviews with 38 participants, consisting of medical staff, patients, and their relatives. Thematic analysis was used to identify and analyze patterns within the collected data.

Results:

Three themes were identified: cross-departmental collaborative practice, financial support practice, and continuity of care. The findings suggest that fundamental cultural changes, such as a policy for intradepartmental referral practices, telemedicine, and a welfare support system, are typically required as remedies for the failure to use PC in Nigeria and other similar contexts.

Conclusions:

This study offered a new understanding that not revealing deeper shared assumptions, and a shared way of thinking that underpins the PC practice within an organization, will have a negative bearing on organizational PC outcomes.

Keywords

Africa

health-care practice

Nigeria

oncology

organizational culture

palliative care

qualitative study

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care (PC) was introduced in Nigeria in the early 1990s through Hospice Nigeria.[1] Some progress has been made since this service was launched. For instance, there has been an increase in the number of PC services in Nigeria, from seven in 2007 to seventeen in 2017.[23] However, PC has continued to be underutilized and not integrated into many of the Nigerian health-care systems, as well as many other African contexts.[45] The 2015 Quality of Death Index shows that Nigeria was ranked the last among other African countries in the area of the palliative and health-care environment, human resources, affordability of care, quality of care, and community engagement.[6] Several studies have reported inadequate funding, limited availability of morphine, religious and cultural meaning-making, insufficient PC professionals, and inadequate professional and public knowledge of PC to be factors that have impacted on PC development in Nigeria.[7891011] Considering that PC is poorly developed in Nigeria,[12] there is a need for a nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the organizational culture, because this could reveal either cultural enablers or inhibitors that may be drawn upon, or eliminated, to improve PC practice.

Organizational culture can be defined as tacit rules that influence behavior and practices within an organization.[13] It can be simply referred to as narratives about what is done and why, including the underpinning presuppositions to the actions.[14] It is argued that health-care organizations are best viewed as consisting of multiple overlapping subcultures, grouped based on specialties, service lines, and professional groups.[1415] The subgroups often compete for resources and status and possess unique attributes that shape their daily routines.[14] The subculture may have nonunified ideologies, leading to cultural divergences that may impact on the collaborative practice; thus, it may influence the quality of care. In the context of the current study, the subculture of PC could range from tacit rules that shape day-to-day PC clinical routines and the patterns of care utilization. It is simply the organizational intricacies that underpin the patterns and practice of PC. Studies that have explored organizational culture in health-care abound, but there is limited empirical evidence about the PC subculture. Specifically, no study has explored the subculture of PC in any Nigerian context, a focus which the current study aimed to address. An understanding of the unique organizational culture could improve outcomes, such as enhanced delivery of improved patient-centered care.[1617] Therefore, the study reported herein offers important actionable insights that can trigger discussion for culture reform.

METHODS

Study design

A qualitative interpretive descriptive design guided this study. Interpretive description is an inductive analytical approach used to generate knowledge relevant to developing clinical understanding, achieved through interpretation of patterns within human experiences and perceptions.[1819] This approach facilitated uncovering the patterns within the organizational culture of PC, perceived to either enable or inhibit service provision and utilization in a Nigerian context, and of practice and theoretical importance for advancing disciplinary knowledge.

Study setting and participants

This study was conducted in a hospital located within the south-eastern geopolitical zone of Nigeria. This was purposively selected for being the largest tertiary hospital with structured provision of in- and outpatient PC to about 40 million people in the south-eastern states, as well as other nearby states. The ranges of PC services rendered in this hospital include pain management, family meetings, bereavement support, counseling, and symptom management.[5]

Nurses, physicians, patients, and their family relatives were purposively selected to participate in this study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) nurses and doctors who had either been involved with provision of PC or with responsibility for decision-making regarding the care of patients receiving PC; (2) patients living with cancer and/or who were receiving PC and were assessed to possess the ability to provide informed consent; and (3) family relatives who were the main carer of the patient who was receiving PC.

Fifty-one participants who met the inclusion criteria were approached to participate in this study, but 13 declined (3 nurses, 3 doctors, 5 patients, and 2 patients' relatives) due to reasons related to busy schedules that they were not interested and because there was no financial benefit. Those who agreed signed written consent form. Overall, 38 participants (10 nurses from palliative and oncology departments, 8 doctors from the palliative unit and the heads of oncology department, a pharmacist, a physiotherapist, 2 social workers, 8 patients, and 8 patients' relatives) participated in the study.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval for this study was initially obtained from the Hospital Research Ethics Committee at the studied hospital in March 2016, but it was renewed in March 2017 with the reference number: NHREC/01/2008B-FWA00002458-1RB00002323.

Data collection

The data were collected through semi-structured face-to-face interview guides facilitated by the primary author (DA) who has expertise in qualitative interviewing. Interview guides were designed in such a way that the open questions were specific for each group of participants, as shown in Table 1.

| Participants groups | Opening questions |

|---|---|

| Members of palliative care team and other health-care professionals (nurses, doctors, pharmacists, physiotherapist, social workers | Can you tell me about the routines or practices of care provision to your patients? |

| Can you tell me about your experiences of services you render to your patients? | |

| What are the issue that promote the care you provide to your patients and the families? | |

| Can you tell me the issues that hinder the routine care of your patients? | |

| Patients | Can you tell me more about the care you are receiving from the health-care staff? |

| Can you explain to me about any issues that encourage and enables you to continue with the care you are receiving | |

| Can you explain to me about issues that hinder the care you are receiving? | |

| Can you tell me about issues that could make you to discontinue with the care you are receiving? | |

| Patients' relatives | Can you tell about the care your family member is receiving here? |

| What are the issues that hamper the care? | |

| Can you tell me the enablers to the routine care being received or receiving from this hospital? |

These open questions were followed by probing questions grounded in participants' responses, to grasp a better understanding of the evolving ideas and patterns. The participants were reassured about their anonymity and confidentiality prior to each interview. This facilitated open and relaxed conversation that enabled an in-depth understanding regarding the organizational culture under investigation. Interviews were conducted individually at locations such as meeting rooms, offices, and bedsides, in consideration of the participants' time and location preferences.

Overall, data collection commenced in March and lasted until June 2017, when data saturation was achieved. Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 min was digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim by the lead author.

Data analysis

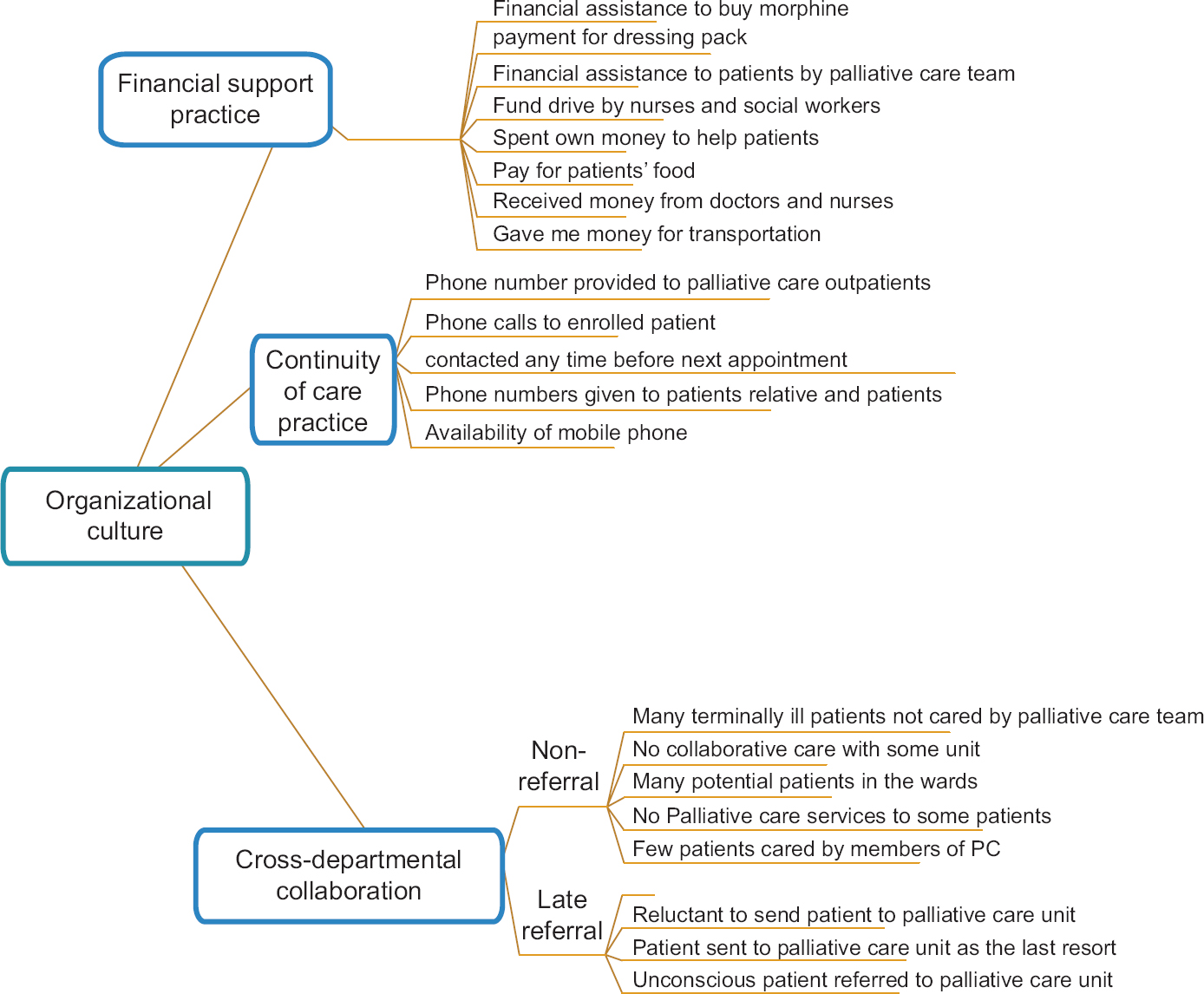

Interview transcripts were imported into the NVivo qualitative data analysis software program (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11). Data were analyzed inductively to identify patterns from the information collected from the participants in accordance with the six steps of thematic analysis developed by Braun and Clark.[20] First, the transcripts were read many times to gain familiarization with the data, followed by coding the transcript by the first author (DA), which yielded many codes. These codes were initially reviewed and grouped by DA based on their similarities to generate patterns regarded as themes. The themes were reviewed by all the authors autonomously, followed by discussions with the coauthors to arrive at a consensus about the correctness of the pattern of ideas about the organizational culture concerning provision and utilization of PC, as shown in Figure 1.

- Thematic framework

Qualitative rigor

Credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability were measures undertaken to maintain the trustworthiness of the findings. Dependability was achieved through data and investigator triangulation, whereby information elicited from different categories of participants were collaboratively analyzed by the coauthors to minimize bias, confirm the analysis, and to enhance the accuracy of the findings. Transferability and conformability were attained by clearly documented methodological and analytical approaches to the study.[21] Again, thick description of the methods and findings was achieved as this would enable the readers to assess the applicability and transferability of the study to another context.[21] Reflexivity was also employed to maintain the credibility of the study.

RESULTS

The three themes generated (cross-departmental collaborative practice, financial support practice, and continuity of care) are reported next.

Cross-departmental collaborative practice

The PC team in the studied hospital consisted of multiprofessionals, specifically, a doctor, four nurses, a physiotherapist, two social workers, and a pharmacist.[5] This PC team collaborated with professionals from other departments to care for cancer patients, but members of PC team expressed two views about interdepartmental collaboration. First, some departments managed cancer and other patients with life-limiting illnesses without collaborating with them:

Many doctors in different departments are reluctant to refer patients to palliative care unit for collaborative care (Pharmacist Lily)

…we don't get a referral from all other units (Nurse 3)

While this view was widespread among the professionals in the PC unit, others alleged that a few referrals from other department for collaborative care were often late:

Most patients are referred to us at their third stage of cancer (Nurse 4)

We do see patients that should need palliative care, but they are not referred to palliative care unit until the late stage of their illness (Social worker 1)

The views of professionals from other departments, when asked either about collaborative care with the PC unit or how they took care of their patients with progressive life-limiting illness, aligned with that of PC team about lack of and/or late referral culture:

We sometimes refer cancer patients to palliative care unit, especially when it is concerned with pain management … (Head of Department 4)

…Eeeh, (Period of silent)…. palliative care unit is still a bit new in this hospital. We do not involve palliative care team with the care of our patients … (Head of Department 2)

The extract above is an indication of the limited collaboration network between the PC unit and other departments in the care of patients with progressive life-threatening illnesses. Nurses from the oncology department of the studied hospital further reiterated that they had repeatedly observed that many patients in the oncology ward and across other wards were not co-managed with the PC team:

All the beds in this ward (oncology ward) is always fully occupied with cancer patients but palliative care team are not always involved with their care (Nurse 7)

Most of patients with progressive life-limiting illnesses are admitted in ward 10 but palliative care team rarely participate in providing care to them (Nurse 9)

These narratives confirmed the organization's norm of lack of, and late, referral, of patients to the PC unit for integrative care. The identified reasons for this organizational culture were struggles for the ownership of patients and lack of awareness about the services of the PC unit:

…many of the doctors usually say this is my patient, I know what to do! (Pharmacist Lily)

I am not aware of what services they can offer and how well they are organised. If we get to know what they do, they get more involved (Head of Department 4)

Referral practice appeared to be tailored to knowledge about the services rendered by the PC team, indicating that poor understanding by doctors from other departments about these services hampered collaborative networks with the PC unit. Again, the first part of the statement “This is my patient, I know what to do” as quoted above, could signify a claim for the ownership of the patient, while the second part of this quote suggests a feeling of defensiveness related to perceived criticisms of their clinical professional knowledge of PC. Another possible explanation for “I know what to do” could be a feeling that referring a patient to the PC unit meant giving up on a patient. It could also mean that the other health-care professionals may have felt that they were providing a good standard of care without collaborating with members of the PC team. Overall, there seemed to be interdepartmental conflict regarding role competition and confusion between members of the PC unit and other departments.

Finally, pain was identified as a compelling factor for referring a patient to the PC unit for collaborative care. For instance, members of the PC team professed that most referrals received from other departments were predominantly patients experiencing severe pain:

Patient is usually referred to the palliative care unit if they experience serious pain (Nurse 2)

They refer patients to us when they feel they can no longer do anything for the patient to relief their pain and sufferings (Doctor 1)

Pain-based referral was a perceived dominant discourse in the studied hospital, indicating that patients without severe pain but with other PC unmet needs may not be referred to the PC unit as psychosocial well-being was not a primary concern of non-PC professionals. As would be expected, the delayed and/or lack of referral exacerbated patients' suffering:

Cancer patients are usually prescribed the wrong regimen of oral liquid morphine by doctors from another department. These patients do experience much pain and sufferings (Pharmacist Lily)

We have seen that most of the cancer patients increasingly suffer due to poor pain management and lack of psychological support from other managing units (Doctor 2)

This provides insight that patients with life-limiting illnesses not co-managed by the PC team tended to experience poor pain relief, because they were deprived of expert pain management and psychological support. This signifies that some terminally ill patients may not have attained an improved quality of life, because of breakdown in the collaborative network.

Financial support practices

The health-care professionals from the PC and oncology unit repeatedly declared that they made financial contributions from their own pockets to assist cancer patients to pay for morphine, dressing packs, chemotherapy, transportation fare, laboratory investigations, and to buy food:

We provide money from our pocket to support indigent patients for their dressing pack, transportation fare and feeding (Nurse 1)

Nurses would have told you that they support these patients with their own money. I also give them money to support these patients (Interview excerpt, Doctor 1)

These health-care professionals seemed to have acted to ameliorate the financial distress experienced by some of the cancer patients, which was confirmed by the patients and their families:

Nurses and the doctors gave me money to support the payment of laboratory investigation for my daughter (Patient relative1)

I appreciate the effort of staff in providing financial help to me.(Patient 8)

The financial support by staff from the PC and oncology unit to cancer patients and their families could be regarded as a unique attribute of these professionals, suggesting their commitment to, and passion for, PC. The financial support was also extended to the funding of patient home visits:

We sometimes pay our own transportation fare to visit our patients at their homes because hospital did not provide mean of transportation (Nurse 2)

This organizational cultural practice could mean that the professionals had performed beyond their normal job role/care responsibilities, driven by the desire to alleviate patients' suffering and to gain self-fulfillment:

When we give them the money, immediately there will be laughter on their face and appreciations (Nurse 4)

…we do it to promote their well-being (Social worker 1)

Plausibly, this practice may be regarded as a cultural enabler for PC, because it facilitated patients' well-being, but the professionals appeared to lack insight of the possible negative consequences of such practice, such as overdependency for help, and confusion of the personal and professional relationships. Overall, it could signify the irresponsibility of the government to support the needs of cancer patients through provision of a financial aid scheme.

Care continuity practice

The members of the PC team reported that they habitually visited patients with life-limiting illnesses in their homes, as well as adopting a telemedicine approach whereby they routinely made mobile phone contact to render support that aimed to improving patients' and their families' well-being. This claim was reinforced by patients and their relatives, who reported that nurses from the PC unit visited their homes to provide services, such as wound dressing, counseling, bed bathing, medication advice, and emotional support:

The nurses have been very helpful because they often make a phone call to encourage me and find out how am feeling. I call them anytime I have any problem and they provided solutions to my problems. Some of the nurses have visited me too, I felt very happy and encouraged (Patient 4)

Nurses spend time to discuss with my mother when they visit us, assist her in bathing, feeding and wound dressing (Patient relative 8)

The patients and their families felt excited about the care continuity practice because it provided an opportunity for the nurses to give care, which seemed to have improved their physical and emotional well-being. However, partial provision of this service was reported because of the purportedly lack of means of transportation and lack of financial support from the management:

We visit families living in town and the close-by villages because there is no financial support or vehicle to travel to far locations for home visit (Nurse 4)

No vehicle to cover both urban and surrounding villages (Doctor 1)

The members of the PC team were most likely keen to provide wider home-based PC follow-up, but the managers of this hospital were perceived not to provide the necessary resources to facilitate its wider coverage.

DISCUSSION

One core element of PC is the collaborative practice of the interdisciplinary team,[22] because the quality care of terminally ill patients and their relatives is complex, requiring skills beyond one profession and/or a department. Although the PC team in the studied hospital consisted of multiprofessionals, the findings showed that cancer patients not only received care from members of the PC unit, but also from other departments within this hospital. Interdepartmental collaboration was an important norm to understand in this hospital because the PC unit depended on referral from other departments/units,[5] and therefore, this norm impacted on the service-users' access and utilization of PC. For instance, weak collaboration between the PC team and other departments, which was manifested by lack of, and late, referral of terminally ill patients to the PC unit led to 'situational deprivation' of the patients from access to, and utilization of, PC.

Notably, inadequate knowledge of the services of the PC team was one of the core reasons for the culture of poor collaborative practice. This is perhaps surprising because one would expect that oncologists' lack of knowledge and skills in PC should trigger a culture that favored referral to the PC team for expert management, consistent with the findings that the severity and complexity of symptoms triggered referral to a PC team.[23] In contrast, in the current study, inadequate knowledge about PC rather hampered the recognition of the necessity to refer terminally ill patients to the PC unit for comanagement. Previous research revealed the idea that professionals' lack of knowledge or skill may facilitate or hinder the referral practice of terminally ill patients.[242526] Again, it is evident that the perception of either providing a good standard of care without collaborating with members of the PC, or to avoid losing patients to the PC team, contributed to the culture of weak cross-departmental collaborative care. These findings aligned with that of Schenker et al.,[27] who found that some oncologists considered themselves to have the knowledge and skill to provide PC, while others thought that referring patients to a PC unit was equivalent to relinquishing their professional responsibilities.

Plausibly, the organizational norm of cross-departmental collaboration was found to be rooted in role competition, complexity, and confusion amongst the different departments who were involved in the provision of care to terminally ill patients. However, some authors have noted that conflicting role demands is a common organizational culture amongst team members of different departments/units.[28] One of the striking revelations in this current study was that the heads of the oncology and PC departments and their members had not identified role conflict or ambiguities as problematic. Therefore, they had not undertaken any action that could lead to organizational cultural reform, such as formulating guidelines in line with APCA standards for interdepartmental collaboration, to clarify role expectations.[29]

In Nigeria, research has shown that most of the patients with cancer have no financial ability to pay for their services,[30] indicating that these patients may not access the services that could improve the quality of their life. In an effort to reduce the financial distress experienced by the patients, the palliative and oncology professionals provided them with financial assistance because there is no financial assistance scheme for this vulnerable group in Nigeria. It is socially acceptable for a health-care provider to give personal money to a patient or patient's relatives in an African context, an act possibly rooted in the African ethos of collectivism/communitarianism.[31] However, this practice may be considered as being unethical and unprofessional in health-care settings in western countries. For instance, a physician who gave money to a patient to help pay for medication was reprimanded for unprofessional boundary-crossing behavior in the US.[32] Offering money to patients could cause some potential risks, such as inappropriate expectations, overdependency for help, and confusion of personal and professional relationships.[32] However, there was no reported negative manifestation of this organizational culture in the current study; instead these acts of kindness reduced suffering for patients and promoted a sense of achievement for the health-care staff. Although the act of financial assistance was a cultural enabler for PC in this organization, it signifies the irresponsibility and failure of the government to support the welfare of cancer patients, through subsidizing the costs of their care or providing insurance schemes, especially for households with poor socioeconomic status.

Finally, the findings revealed that patients and their families felt a sense of being valued because of the care continuity received from the members of the PC team. Evidence has revealed that telemedicine in PC proves useful because it offers the opportunity to enhance the quality of care.[33] In the current study, this was limited to mobile phone conversations with patients and their families while at home, revealing an area for organizational enhancement, such as upgrading to a mobile telesystem that will allow video consultations between patients at home and professionals in the hospital.[34] Again, nurses in the current study also engaged in home visits to continue with care provision. However, this service was limited to service-users near the hospital environs due to lack of transportation and lack of financial support from the management, revealing an area for improvement.

Study contributions

This study has provided a rich qualitative account of organizational culture in the Nigerian context from the perspectives of the health-care professionals, patients, and their families which can be extrapolated to another similar context. First, this research revealed that weak interdepartmental collaboration between the PC team and other departments in Nigerian hospitals, or other similar settings, increases avoidable deprivation of care, leading to poor quality of life for patients. Therefore, cultural reform, such as formulating guidelines at the national and hospital level for collaborative practice in the care of cancer and other terminally ill patients, is required in Nigeria. Second, the findings also revealed that any health-care system without a social support system for the management of cancer will possibly lead to a situation whereby the health-care professionals will be instinctively compelled to compensate for patients' poor economic status. Thus, we argue that a welfare support package for cancer management is the cultural change required to remedy this cultural shortcoming. Third, the government of Nigeria and international organizations could use the findings from this paper as an indication of the need to develop and support the implementation of telemedicine in PC, as this will be a step to cushion the effect of inadequate PC services as well as to ensure continuity of care for mostly rural dwellers in need of PC.

Study limitations

This study was conducted in one study setting, suggesting that it is limited in terms of population generalizability, meaning that the findings may be not be applicable to the entire population of patients with cancer/other progressive life limiting illnesses and the professionals who provide care to them. However, this paper does contribute in terms of theoretical and conceptual generalization, meaning that the findings can be extrapolated to similar contexts. Qualitative research aims to make a logical generalization to a theoretical understanding of a similar class of phenomena.[21]

CONCLUSIONS

This current study has provided new insights, namely, that organizational culture could either enhance or impede the provision and utilization of PC. Inadequate cross-departmental collaboration was found to be an inhibitor of PC practice; therefore, a policy action is required. However, financial support and continuity of care were the organizational norms that promoted PC, revealing an area to be strengthened for PC development. Finally, we argued that the failure of the government and health-care professionals of any country to take responsibility and support the provision and utilization of PC will reinforce the existing PC disparities, and increase mortality, especially in low-income countries.

Financial support and sponsorship

Tertiary Education Trust Fund, Nigeria, in collaboration with Ebonyi State University is acknowledged for financial support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Hospice and Palliative Care in Africa; A Review of Developments and Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Hospice and palliative care development in Africa; A multi-method review of services and experiences. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2007;33:698-710.

- [Google Scholar]

- (2017a) APCA Atlas of Palliative Care in Africa. USA: IAHPC Press; 2017.

- Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2013;45:1094-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the organization of hospital-based palliative care in a Nigerian Hospital: An ethnographic study. Indian J Palliative Care. 2019;25:218.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2015. The 2015 Quality of Death Index Ranking Palliative Care Across the World. Available from: http://wwweiuperspectiveseconomistcom/healthcare/2015-quality-death-index

- Construction of meanings during life-limiting illnesses and its impacts on palliative care: Ethnographic study in an African context. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28:2201-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care needs evaluation in untreated patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Ibadan, Nigeria. , Afr J Haematol Oncol. 2010;1:48-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care: Supporting adult cancer patients in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Palliat Care Med. 2016;6:258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Home-based palliative care for adult cancer patients in Ibadan – A three-year review. E Cancer Med Sci. 2014;8:490.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care in developing countries: University of Ilorin teaching hospital experience. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:222.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global perspectives on palliative care: Nigerian context. In: Holtslander L, Peacock S, Bally J, eds. Hospice Palliative Home Care and Bereavement Support. Cham: Springer; 2019.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

- Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. BMJ. 2018;363:k4907.

- [Google Scholar]

- The struggle to improve patient care in the face of professional boundaries. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:807-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of organizational culture on patient access, care continuity, and experience of primary care. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2016;39:242-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: Systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017708.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interpretive Description. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2008.

- Strengths and challenges in the use of interpretive description: Reflections arising from a study of the moral experience of health professionals in humanitarian work. Q Health Res. 2009;19:1284-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increasing rigor and reducing bias in qualitative research: A document analysis of parliamentary debates using applied thematic analysis. Q Soc Work. 2019;18:965-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Australian general practitioners' and oncology specialists' perceptions of barriers and facilitators of access to specialist palliative care services. J Palliative Med. 2011;14:429-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why do health professionals refer individual patients to specialist day hospice care? J Palliative Med. 2011;14:133-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- What are the barriers faced by medical oncologists in initiating discussion of palliative care? A qualitative study in Flanders, Belgium. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3873-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- What influence referrals within community palliative care services? A qualitative case study. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:137-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative clinics. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:37-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organisational Behaviour (2nd ed). United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011.

- 2010. APCA Standards for Providing Quality Palliative Care Across Africa. Available from: http://wwwthewhpcaorg/images/resources/npsg/APCA_Standards_Africapdf

- Social and health system complexities impacting on decision-making for utilization of oncology and palliative care in an african context: A qualitative study. J Palliative Care. 2020;35:185-191.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee PH, Roux AP, eds. Philosophy from Africa (2nd ed). Cape Town: Oxford University Press of Southern Africa; 2002.

- I got 99 problems, and eHealth is one. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;245:258-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Telemedicine in palliative care: Implementation of new technologies to overcome structural challenges in the care of neurological patients. Frontiers Neurol. 2019;10:510.

- [Google Scholar]