Translate this page into:

Home-based Palliative Services under Two Local Self-government Institutions of Kerala, India: An Assessment of Compliance with Policy and Guidelines to Local Self-government Institutions

Address for correspondence: Ms. Rajeev Jayalakshmi, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Kharagpur, West Bengal, India. E-mail: jrajeev.lakshmi1@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

In contrast to India's poor performance in palliative and end-of-life care, the state of Kerala has gained considerable attention for its palliative care (PC) policy. This study tried to understand the structure, organization, and delivery of the program currently offered to the rural population, and its conformity to the state's PC policy and guidelines for Local Self-government Institutions (LSGIs).

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive research design involving a review of Kerala palliative policy and guidelines for LSGIs was followed by direct field observation and interviews of stakeholders. Two LSGIs in rural Kerala served also by a nongovernmental organization (NGO), were selected. Data were collected from health workers (doctors, nurses, and PC nurses), government stakeholders (LSGI members and representatives of the National Health Mission), and the health workers and officials of NGO.

Results:

The program in two LSGIs varies considerably in terms of composition of the palliative team, infrastructure and human resource, cost, and type of service provided to the community. A comparative assessment with a nongovernmental service provider shows that the services offered by the LSGIs seemed to be restricted in scope to meet the needs of the resource-stricken community. Compliance with policy guidelines seems to be poor for both the LSGIs.

Conclusions:

Despite a robust policy, the palliative program lacks a public health approach to end-of-life care. A structural reconfiguration of the delivery system is needed, involving greater state responsibility and political will in integrating PC within a broader social organization of care.

Keywords

Compliance to policy

home-based program

Kerala palliative care policy

Local Self-government Institution guidelines

INTRODUCTION

The Lien Foundation's commissioned studies in 2010 and 2015 rate India poorly in the quality of dying.[12] One of the reasons for this is the slow progress in palliative and end-of-life care.[3] A notable exception is the state of Kerala in Southern India characterized by high development indicators. Unfortunately, the state is witnessing high morbidity levels, a graying population, and high prevalence of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and cancer.[456] Kerala also reports a declining revenue expenditure on health.[7] It is in this context that the palliative care (PC) policy introduced to serve the needs of the community, especially those residing in rural resource-strapped areas, needs re-examination.

Kerala pain and palliative care policy: An overview

Kerala announced the pain and PC policy in 2008 with an emphasis on community-based care and became the first state in India in this respect.[8] The cornerstone of the policy is the home-care projects by Local Self-government Institutions (LSGIs - the primary level administrative system in India) in association with primary health-care system.[9] This initiative received worldwide attention for resource-poor settings.[10] The policy envisaged a public health approach and to provide holistic care to those with life-limiting illnesses through home-based care with their family as the core unit of care. It proposed extensive training of existing doctors, nurses, Multipurpose Health Workers such as junior health inspectors (JHIs) and junior public health nurses (JPHNs) and their supervisors, and elected members to LSGIs to provide an integrated care with active community engagement. PC was to be integrated into field level activities of existing Multipurpose Health Workers and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). Essential medicines including oral morphine were to be available through PC units/Primary Health Centers (PHCs) and other government hospitals. There was an expressed need for monitoring for quality assurance (Kerala pain and PC policy draft-2.2.b. 6).[8]

The policy speaks of involvement of all administrative health tiers in PC. Medical officers of PHCs and Community Health Centers (CHCs) were to coordinate with Community-based organizations (CBOs) and LSGIs in developing a common platform for palliative service delivery at the primary level (3.2.a and 3.2.b). An important feature of the program was developing a rational drug policy (5: 5.1, 5.2, 5.3) and providing greater treatment choices through integrative models using plural medical systems such as Ayurveda and homeopathy (6.1).[8]

Guidelines to Local Self-government Institutions: An overview

The policy was implemented as part of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). The State Health Society of NRHM that has been named Arogyakeralam, in collaboration with Institute of Palliative Medicine, Kozhikode, did pilot district level projects. Encouraged by the results of the project, NRHM (Kerala) initiated State level PC Project in 2008. Subsequently, to the policy document, the Government of Kerala issued orders encouraging the involvement of LSGIs in PC.[11] It also gave orders for facilitating the collaboration of government hospitals including PHCs in the process.[12] Kerala Institute of Local Administration, Thrissur, an autonomous institution with the objective of training, research, and consultancy in decentralized governance and administration, published the guidelines for LSGIs after a review of the policy implementation in 2011. The guidelines were revised in 2013 and according to which PC became a mandatory project for all LSGIs in Kerala.[13] Thus, the LSGIs are primarily responsible for the overall implementation of the program, and not merely a funding agency or facilitator. These guidelines primarily focused on the following: preparation of annual plan including the budget allocation for each financial year, forming home care team and training, coordination between the services provided by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other CBOs, and monitoring and evaluation of the PC program.

The present study has two-fold objectives: first, to understand the structure of PC currently offered to rural population, and second, to assess how far the program organization and service structures conform to the policy and suggested guidelines for LSGIs formulated by the state after the first review of the policy implementation in 2011.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Poovar and Azhur are two rural areas provided home-based PC by the LSGIs (called Gram Panchayats) and an NGO. Initially, the areas were served only by the NGO. The Government PC service started in Azhur and Poovar in 2013 and 2010–11, respectively. At present, the NGO, as well as Poovar CHC, in collaboration with a medical officer at Government Ayurvedic Health Centre provide PC services in Poovar. At Azhur, the Regional Cancer Center, Thiruvananthapuram, also conducts home visits and provides follow-up palliative services to cancer patients undergoing treatment.

The jurisdictional areas served by the LSGIs have a population of 20,056 (Poovar) and 28,331 (Azhur) with a high concentration of scheduled castes – 2586 in Poovar and 5535 in Azhur. The residents are mainly occupied in fishing and manual labor in Poovar, and in Coir industry and other manual labor in Azhur. Around 47% of the residents in Azhur were below the poverty line. Both the regions have a large number of elderly people. Although precise estimates for Poovar are unavailable, in Azhur, there are 2008 males and 2045 females above the age of sixty.

The present study used a descriptive research design, focusing on primary level PC services offered in the above-mentioned two LSGIs. The structure, organization, and pattern of home care delivery by both the government and NGO were assessed, and data were collected from health workers (doctors, nurses, and PC nurses) from both the NGO and public sector. Two officials from the national health mission in charge of PC program were also interviewed. Next, the compliance of the LSGIs to the policy was understood by comparing the existing health delivery with the stated ideals as suggested in the policy draft and guidelines to LSGIs.

The information on the home-based PC provided by NGO was collected through direct interviews with the chief executive officer and director of the organization and field visits with their team as well.

RESULTS

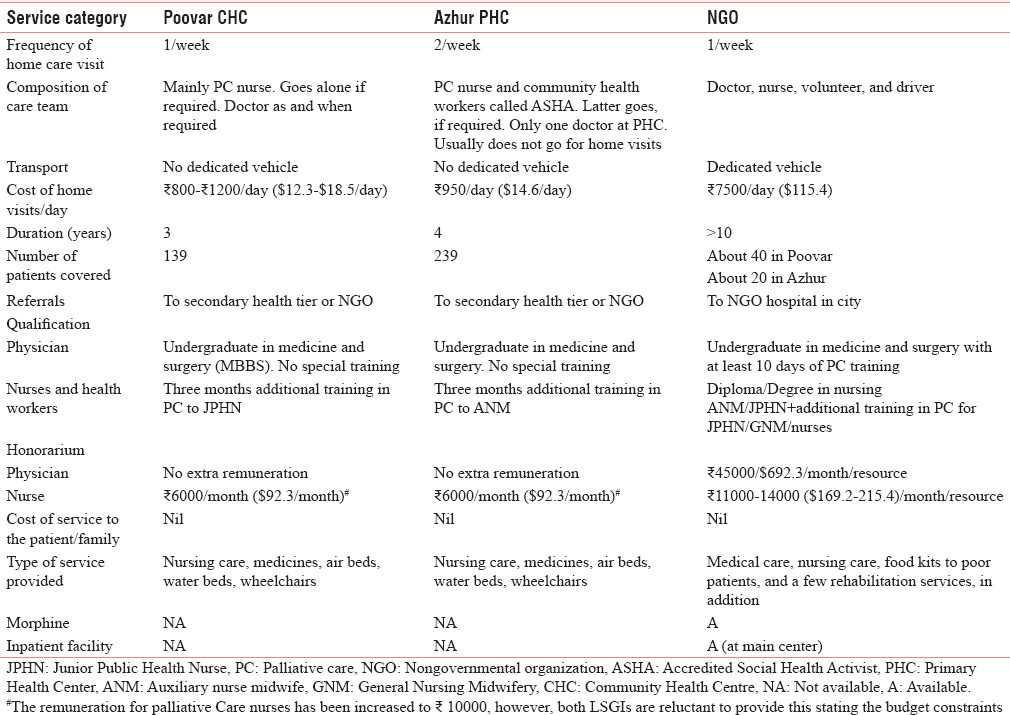

There were about 139 patients in Poovar and 239 patients in Azhur taking PC services provided by government health centers. Among them, 28 patients with catheter or bedsores received palliation in Poovar and 71 in Azhur. Most of them were suffering from serious multiple morbidities including noncommunicable diseases, mobility issues, and sensory and motor impairments. There were a few participants without food and shelter.[14] Table 1 provides a comparative description of the nature and organization of PC services provided by two LSGIs and the NGO operating in Poovar and Azhur.

It is clear from a comparison of the three service providers that the palliative program in the region does not have a uniform structure in terms of workforce deployment, training of health workers, infrastructure availability, and composition of the palliative team. It is evident from the study that government palliative teams were merely nurse-led, while the NGO operating in that region had a more professional approach in terms of the composition of the team. Perhaps the reason for the dominance of nurse-led teams in government programs is the sheer workload of the doctors and poor motivation due to the lack of extra honorarium for palliative services. This is a major drawback of the policy itself since it relied on medical officers who are already in service rather than appointing new staffs. The nodal officer from NHM also emphasized the need of a dedicated palliative physician to ensure continuity of care thereby improving program efficiency each LSGI.

The study found that a rational structure of work allocation has not been made for allied health workers, particularly for PC nurses who seemed to be overworked. It may be mentioned that initially, the policy had proposed augmenting field level and subcenter level services. Male and female Multipurpose Health Workers were expected to provide comprehensive primary health-care services at the household level through the subcenters and at the PHCs; they were to be given necessary orientation cum skill development training to play a major role along with the CBO volunteers and family members. However, in reality, the entire burden seems to have fallen on the palliative nurses who were also found to be overloaded with responsibilities for which they did not have the requisite skills, for instance, formulating budgets. Poovar and Azhur had only one palliative nurse, each.

The study showed poor frequency of home care visits in both places: 4–6 home visits in Poovar and 8–9 home visits in Azhur in a month. About 6–12 patients were visited per day according to the patients' condition. It is impossible to reach all patients at this rate in both LSGIs. For those patients who needed urgent attention, the family members “called” the PC nurse and had to bear the cost of vehicle charges (back and forth). These “informal” visits were more frequent in Poovar since the schedule of home visit was arranged according to the convenience of JHI or JPHN accompanying the team rather than the needs of the families.

Patients with urinary catheters, bedsores, or those needing special nursing care could be visited only once in a month indicating a serious care deficit. Others were visited once in 2 or 3 months according to the severity of their illnesses. One important reason could be a lack of workforce and dedicated transport for such a purpose. The revised guidelines for LSGIs mention that transport facilities for home care need to be arranged from the budget earmarked for PC. The vehicle owned by the health center could be used if available, otherwise hired for the same purpose. In Poovar, home care team was found to use the hospital vehicle during scheduled home visits; however, for unscheduled visits, the patient's family had to pay for the vehicle charge back and forth. Thus, except for the NGO, which had its own vehicle, transportation was a big problem in maintaining the quality of services. However, providing better services resulted in huge escalation of cost per home visit, as in the case of the NGO. This indicates the need for more serious cost analysis to ascertain whether home palliation in its present form, may be considered as the best model when resources are scarce.

A great strength of the program medicines dispersed at free of cost, whether run by the NGO or the government. Making essential medicines for PC available to patients covered by PC services through PC units/PHCs/other government hospitals are an important component of the policy. However, field observations show that not all patients in need get the medicines from their service providers; the logistics for disbursement also remains rather cumbersome except for the NGO. Families had to collect medicines from the facilities rather than having them delivered at home by the home care team, thus entailing extra time and effort. Availability of morphine remains problematic, except for the NGO.

The palliative home care as provided to the two rural areas lacks an adequate social welfare provision for the poor. It also lacks alternative institutional structures for those who are living and dying alone and under desperate circumstances. Emergency referrals facilities to acute centers are also absent.

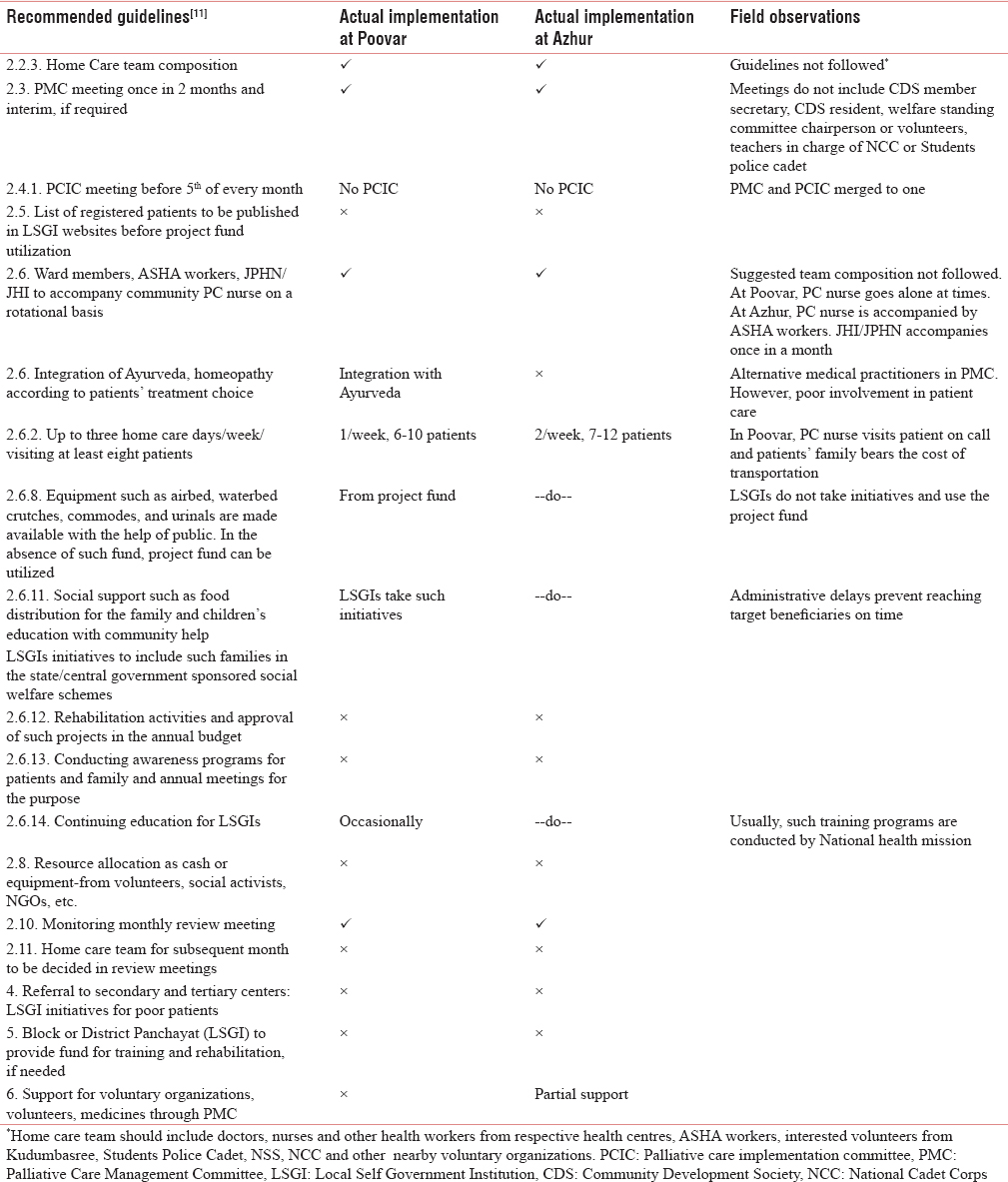

PC policy envisaged LSGIs as the prime implementation authority to coordinate the services. Table 2 compares the two LSGIs in terms of their adherence to the guidelines formulated in 2013 after a review of implementation of the PC policy.

Table 2 shows glaring gaps in adherence to the guidelines formulated for the LSGIs. The policy had envisaged an integrated service provision with family as the core unit of care. Although the mandatory home care project is run by both the LSGIs, the home care team does not follow the suggested composition, and it is rarely planned in the review meetings.

PC Management Committee meetings, though regular, do not enlist wide participation involving members enlisted in the guidelines. The revised guidelines for LSGIs clearly mention involvement of LSGI members, medical officers, nurses, field workers, and ASHAs from the health centers under the jurisdiction of LSGI and representatives from NGOs, volunteers from the community, representatives of Kudumbasree Community Development Societies (community-based organization), and teachers in charge of Students Police Cadet, National Service Scheme, and National Cadet Corps (schools- and college-based youth development schemes). In contravention of the suggested guidelines, the meetings did not involve wide participation. The role of LSGIs appears mainly restricted to funding – its allocation and spending, rather than actively devising an organizational and care logistics geared toward improved service quality. The budget allocation also showed great variability. The amount, meant primarily for dispensing medicines, meeting home care costs, and for providing remuneration to nurses, was reported as insufficient by PC nurses of both the LSGIs.

Another important finding from the field was that health inspectors, who had little training in higher-level management functions, often devised the annual outlays based on the report by PC nurses who were also poorly qualified. Thus, annual budget outlays were repetitive and unreflective of ground realities. Moreover, NRHM instructions on annual planning and budgeting were overlooked resulting in a weak health delivery system and poor outcomes. While both LSGIs provide some social support services but administrative delays prevent good outcomes with the result that a mere clinical approach to palliation has resulted without any rehabilitation activities. There is a little initiative to garner more funds from external sources and engage in continuing education activities and rehabilitation. Most of the educational activities are conducted by the national health mission rather than by the LSGIs.

Public-private linkages are important for sustainability of any program at community level. The study found considerable hostility among service providers. In both LSGIs, there were open conflicts between LSGI members and health workers regarding fund utilization, membership, and representation in meetings. Conflict between NGOs and government providers was very overt to a level causing open arguments. In this sense, the initial aim of the government to utilize the experience of CBOs/NGOs and actively work with them seems to have failed.

The policy envisaged a proper monitoring system in the state to facilitate quality assurance. Clear instructions were provided to LSGIs on how to monitoring the program and give suggestions for improvement. However, in practice, the meetings usually remain focused on fund expenditure rather than on quality of services. Moreover, a guideline for quality control was proposed to be set up at the state level with a monitoring/evaluating mechanism at the district level. Further, it envisaged developing a system to document and compile data on the PC-related activities and patient population at district and state level. However, field research shows serious flaws with irregular meetings and poor record of proceedings to guide action.

Central to assessment of quality of services is the question of training of health workers. LSGIs rarely engaged themselves in training. The existing home care team was also inadequately trained. The nodal officer admitted that the basic qualification of a PC nurse was insufficient to equip her with good caring skills. Health coordinators such as the JHI/JPHN were also overloaded with multiple duties in ongoing health programs. Continuing education was occasionally provided, but no volunteers were selected or trained in both LSGIs.

Contrary to the policy guidelines, family empowerment as an outcome measure for the success of palliation is also rather weak. Families clearly lacked skills in handling the bedridden and dying. Poverty and dismal home environments added to the burden of caregiving. Although the need for care became more pronounced as patients became completely bedridden and dependent, family involvement in caring was restricted, superficial, and confined to days when home visits were expected. Supportive care to families through pension/welfare inputs is also weak due to slow administrative system.

An important feature of any health delivery program is a proper supply–demand assessment of medicines and equipment within a proper logistics cycle to ensure just distribution. The study found problems in distribution and availability of morphine. In addition, the PC structure, despite its clinical focus, lacked many specialist doctors such as psychiatrists, geriatricians, and physiotherapists. There was also a lack of integration of biomedicine with indigenous healing traditions. Only one LSGI could accommodate indigenous medicine; the other two providers failed to integrate this with a dominant biomedical approach despite Ayurveda's confirmed therapeutic potential in treating bedsores, joint pains, etc.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite having made much progress, the program in two LSGIs is still short of a public health approach, and major guidelines of the palliative policy seem to have been given a miss. It also lacks the flavor of a community-owned program with a committed organizational structure, dedicated staff and delivery mechanism, seamless care through continuous monitoring, high frequency of visits, and adequate referrals. Finally, it appears too fragmented and restricted in its scope to meet the needs of the poor, the homeless, and those without caregivers unless it is located within an inclusive long-term care strategy involving a mix of health and social security measures. Evidently, this would require a huge structural reconfiguration of the delivery system – a task whose magnitude and profundity necessitate greater state responsibility and political will in including palliation within a broader social organization of care.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study gives a clear lens toward the limitations of the PC program to provide holistic care in resource-poor settings. The latest revision of the guidelines to the LSGI was done in September 2015. The present study is based on the data collected in March and April 2015 and findings are based on revised guidelines of 2013. Since the study covers only two villages of Kerala, we cannot generalize the findings to the whole state.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Ministry of Human Resource Development, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The study is part of the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India funded project: “Improving End-of-Life Care for the Elderly through Indic Perspectives on Ageing and Dying,” Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, West Bengal, India.

REFERENCES

- Economist Intelligence Unit. In: The Quality of Death: Ranking-End-of-Life Care Across the World. London: Lien Foundation; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economist Intelligence Unit. In: The 2015 Quality of Death Index. Ranking Palliative Care Across the World. London: Lien Foundation; 2015.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospice and palliative care development in India: A multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:583-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index for India's States. UNDP, India; 2011. p. :15-20.

- Regional Cancer Centre. Incidence of Cancer in Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram. Available from: http://www.rcctvm.org/lifestyle%20and%20cancer.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Age-specific analysis of reported morbidity in Kerala, India. World Health Popul. 2007;9:98-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Government health services in Kerala who benefits? Econ Polit Wkly. 2001;36:3071-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Family Welfare. Palliative Care Policy for Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram, Policy Draft. Governemnt of Kerala 2008

- [Google Scholar]

- The neighbourhood network in Kerala. In: Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A, eds. International Perspectives on Public Health and Palliative Care. London, New York: Routledge; 2012. p. :98-109.

- [Google Scholar]

- Government of Kerala. Local Self Government Department. GO Number 66373/D.A1/2009, Dated 11 February, 2009

- [Google Scholar]

- Government of Kerala. Implementation of Pain and Palliative Care Policy. Circular. PH 6/068463, Dated 02 July, 2009. Directorate of Health Services

- [Google Scholar]

- Kerala Institute of Local Administration. Revised Guidelines on Palliative Care by Local Self Governments of Kerala. Government of Kerala 2013

- [Google Scholar]

- Endof-life characteristics of the elderly: An assessment of home-based palliative services in two panchayats of Kerala. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:491-8.

- [Google Scholar]