Translate this page into:

Linguistic Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual-Well-being-Expanded Version 4 Tool into Malayalam Language and its Feasibility in Advanced Cancer Patients Receiving Palliative Care

*Corresponding author: M. S. Biji, Department of Cancer Palliative Medicine, Malabar Cancer Centre, Kannur Thalassery, Kerala, India. bijims@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Biji MS, Nair S, Shenoy PK, Spruijt O, Venkateswaran C, Rajashree KC, et al. Linguistic Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual-Well-being-Expanded Version 4 Tool into Malayalam Language and its Feasibility in Advanced Cancer Patients Receiving Palliative Care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2024;30:358-65. doi: 10.25259/IJPC_79_2024

Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to validate the ‘Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual-Well-being-Expanded(FACIT-SpEx) Version 4’ tool in Malayalam and assess its feasibility among advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care.

Materials and Methods:

The study was carried out at the outpatient Department of Cancer Palliative Medicine of Malabar Cancer Centre between November 2022 and June 2023. Initially, the FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 tool with 23 items was translated into the Malayalam language with a forward-backward translation procedure. This was followed by pilot testing in 10 advanced adult cancer patients receiving palliative care who could read and comprehend the Malayalam language. After answering the draft version of the validated tool, patients responded to questions from a Malayalam-translated cognitive debriefing script.

Results:

The process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation went on smoothly with very few hurdles. The Malayalam terms used in three items Sp7, Sp9 and Sp23 when back translated were found to be different from the source. These issues were resolved with the use of the most suitable translations and closest equivalents available in Malayalam. In the pilot testing, the majority (70%) of the patients were female. The mean age of patients was 45.90 (standard deviation [SD] = 7.62) years. Carcinoma breast (50%) was the most common type of cancer. All the patients knew their diagnosis, while only 80% knew the prognosis. Almost 90% of the patients were receiving some form of palliative anticancer treatment. All patients completed the draft version of the validated tool. The mean spiritual well-being score measured using this validated tool was 71.20 (SD = 15.10). Analysis of the debriefing interviews revealed that the Malayalam version was easy to complete, relevant, and appropriate.

Conclusion:

Linguistic validation and cognitive debriefing produced the Malayalam translated FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 tool conceptually equivalent to the original FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 tool, and it is feasible for its use.

Keywords

Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-spiritual-well-being-expanded

Validation

Malayalam

Linguistic

INTRODUCTION

Cancer patients experience physical and psychological distress throughout their cancer trajectory. In addition to this, they may face deep existential challenges affecting their quality of life.[1-3] Spirituality is recognised as one of the eight distinct domains within the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care guidelines.[4] It is defined as the way people find meaning and purpose in life, and how they experience connectedness to self, others, the significant or sacred.[5] Spirituality and religion have a role to play in the way patients cope with their cancer diagnosis and continue through treatment, survival, recurrence, and dying.[6,7] Spirituality and religiosity are closely related though not the same.[8] Religiosity refers to the beliefs and practices associated with a particular religious worldview and community while spirituality may be experienced in and/or outside of a specific religious context.[9,10]

Multiple studies have been done among cancer patients and survivors to assess their spiritual well-being and these studies have used different tools to assess spiritual well-being.[11-14] Levels of spiritual well-being have been reported to be different among cancer patients and survivors from different parts of the world. Although spirituality’s role in health and medicine is important, there is a lack of literature and gaps in understanding its impact in the Indian context.[15] Many 111more inpatients desire conversations about their religious and spiritual concerns than those who actually experience such conversations.[16] Although there is a need for spiritual care for patients, especially at the end of life, routine provision of spiritual care is rare.[17] The possible explanations include lack of time,[18,19] concerns regarding the appropriateness of spiritual care[20,21] and poor training.[22] In India, offering spiritual care is challenging due to the wide variety of religions and cultures, along with the absence of reliable tools to measure spirituality.[23] Most spirituality methods come from Western countries and need to be used carefully in India.[24]

Tools to measure spiritual well-being

Several tools are available to measure spiritual well-being. There is no validated tool in local vernacular form to use in our population. One commonly used tool is the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp) tool. FACIT-Sp is a 12-item self-administered questionnaire that explores the three sub-domains of spiritual well-being: peace, meaning, and faith. It is not limited to any one religion or spiritual tradition. FACIT-Sp-expanded (FACIT-Sp-Ex) is the expanded version of FACIT-Sp. In addition to the original 12 items in FACIT-Sp, this tool has 11 other items that address other aspects of spiritual well-being, namely, connectedness, love, gratitude, and forgiveness, grouped as the fourth sub-domain – the relational subscale [Table 1].[25] We chose to use the FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 tool as the relational content of the items is very relevant to Indian culture. In India, the family is centrally involved in most decision-making.[26] This may also provide additional depth of information regarding spiritual well-being and health outcomes in our population. Administration of this tool in a regional language will help us in capturing spiritual well-being in our population and compare the level of spiritual well-being among our patients against the international data. This may help us to identify patients who may need interventions. The objective of the present study was to translate the FACITSp-Ex version 4 tool into the Malayalam language and to linguistically validate the tool among advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care with or without their cancer treatment.

| Not at all | A little bit | Some-what | Quite a bit | Very much | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp13 | I feel connected to a higher power (or God) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp14 | I feel connected to other people | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp15 | I feel loved | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp16 | I feel love for others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp17 | I am able to forgive others for any harm they have ever caused me | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp18 | I feel forgiven for any harm I may have ever caused | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp19 | Throughout the course of my day, I feel a sense of thankfulness for my life | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp20 | Throughout the course of my day, I feel a sense of thankfulness for what others bring to my life | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp21 | I feel hopeful | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp22 | I feel a sense of appreciation for the beauty of nature | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sp23 | I feel compassion for others in the difficulties they are facing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

FACIT-Sp-Ex: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual-Well-being-Expanded

Tool translation and cross-cultural adaptation

Tools used in research need to be translated and cross-culturally adapted into the language of the research[27] and the process needs to be systematic.[28] One of the different methods available for this process is the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy (FACIT) translation methodology with a double-back translation. The FACIT translation methodology consists of several steps, including pilot testing of the tool with ten patients in the target language. The aim of the FACIT translation methodology is to produce translations of the original source instrument that have conceptual and semantic equivalence with the source version.[29,30] Conceptual equivalence refers to the theoretical constructs as the source, while semantic equivalence refers to the translated items expressing the same meaning as the source.[28] Linguistic validation is the entire process for the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the instrument into the target language maintaining the conceptual and semantic equivalence with the source version.[31]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4

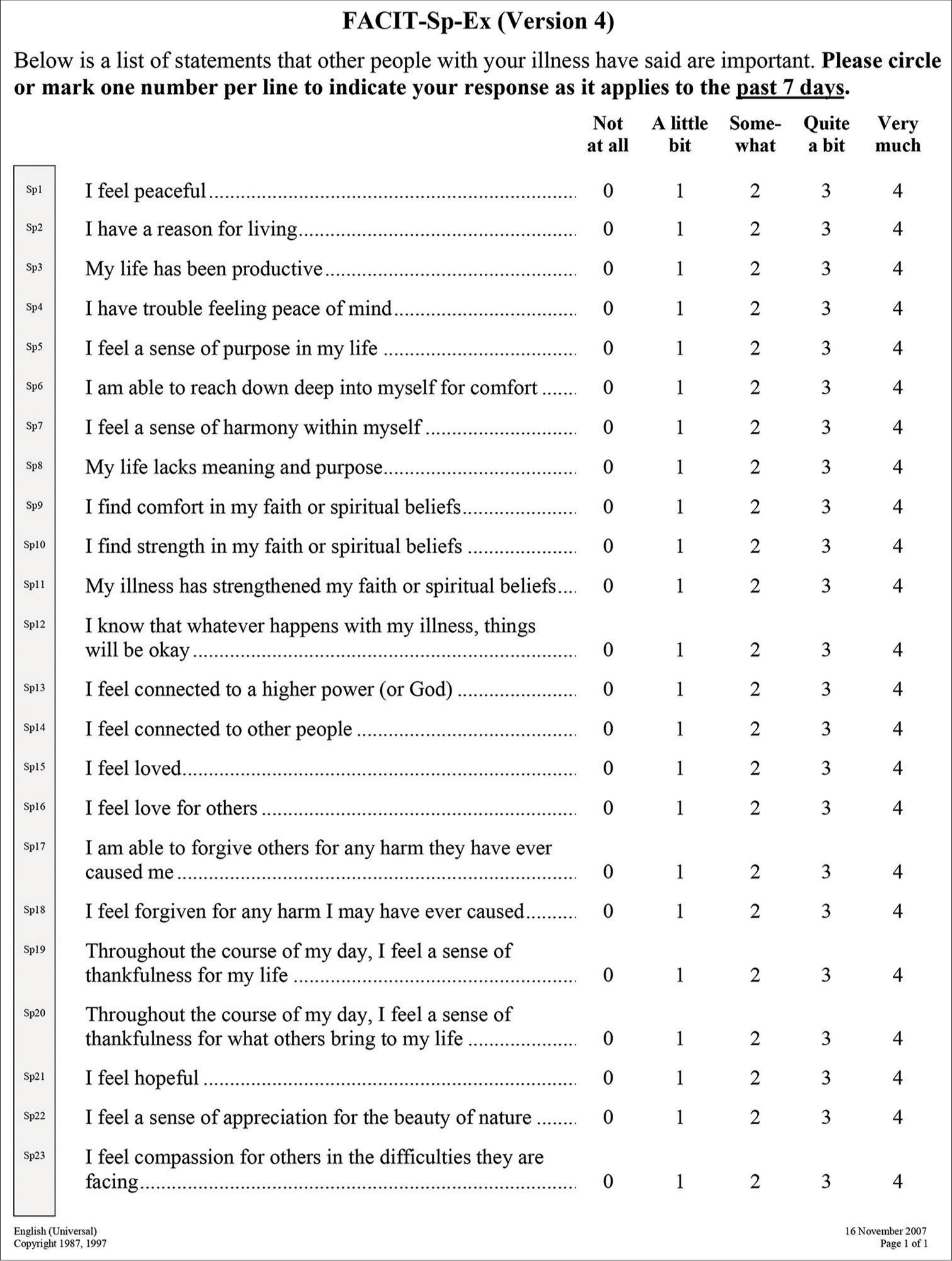

FACIT-Sp-Ex [Figure 1] is a 23-item questionnaire published in 1999 as a brief measure to assess spiritual well-being which assesses meaning (items 2, 3, 5 and 8 reverse-coded), peace (items 1, 4 reverse-coded, 6 and 7), faith (items 9, 10, 11 and 12) and relational aspects of spirituality (13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23) on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = Not at all, 1 = Little bit, 2 = Some-what, 3 = Quite a bit and 4 = Very much). The FACIT-Sp-Ex is scored by summing the item scores in each subscale and then summing the subscale scores to yield the total score. The score ranges from 0 to 92, with a higher score indicating greater overall spiritual well-being.[32]

- The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual-Well-being-Expanded.

Translation of FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4

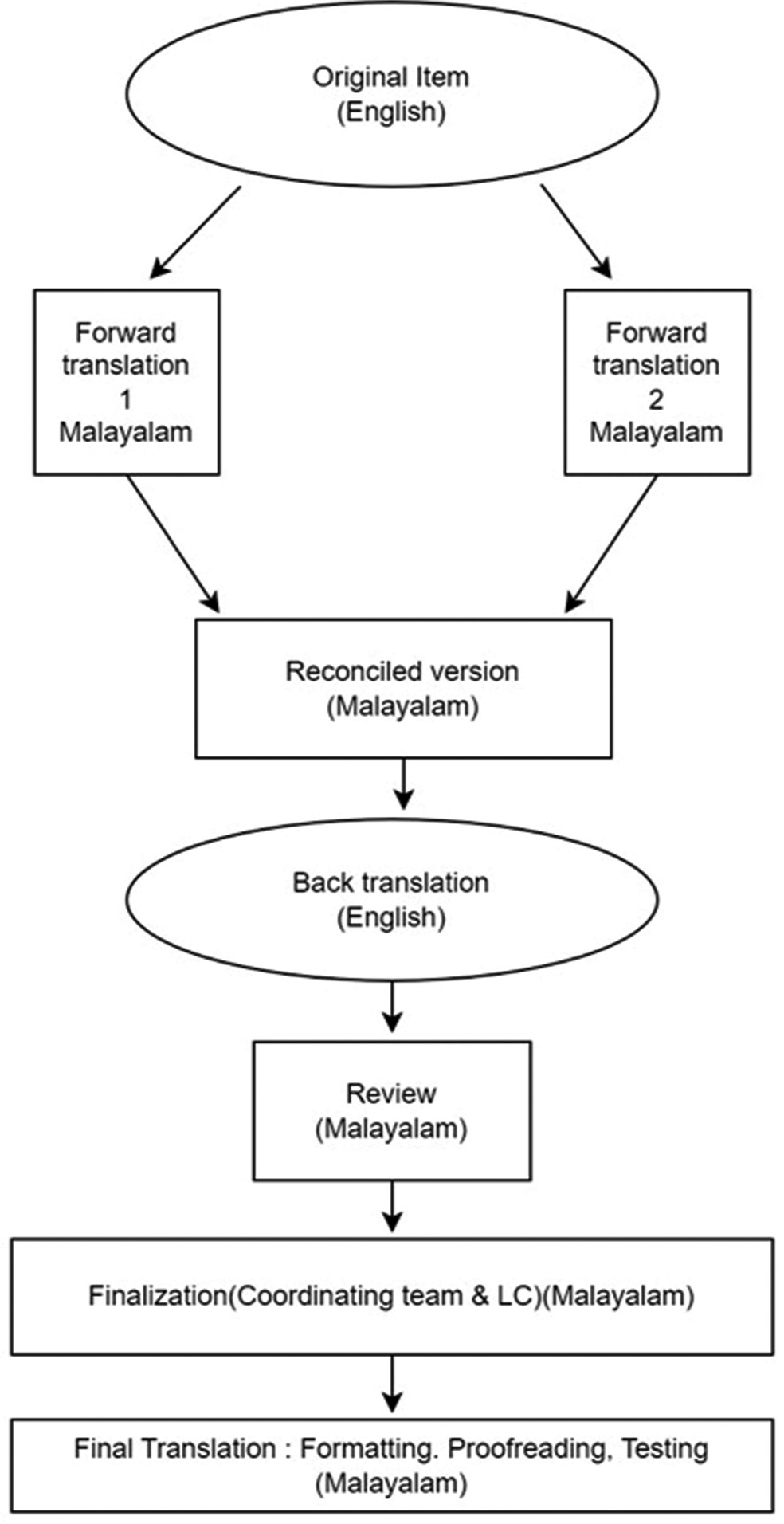

The FACIT-Sp-Ex Version 4 tool was translated into Malayalam following the FACIT translation methodology.[29,30]A document called the Malayalam Item History (MAL IH) was used to track each step of the translation and cultural adaptation process, along with the results. A flowchart of the FACIT translation methodology is outlined in Figure 2

- Flow chart of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy translational methodology.

The translation process involved translating the English version of the FACIT-Sp-Ex Version 4 into Malayalam using a forward-backward translation method. First, two independent translators fluent in both English and Malayalam translated the tool into Malayalam, ensuring they captured the meaning of each item. Their translations were then compared and merged by a third translator. Next, a fourth translator backtranslated the Malayalam version into English to ensure accuracy of the translation. In the next step, the MAL IH document, consisting of the forward translations, the reconciled, and the back translations, was sent to the FACIT team. This back-translation was compared with the original English version by the FACIT team, and any discrepancies were noted. A fifth translator reviewed all translations and comments, created a draft version, and corrected any grammatical, spelling, or formatting errors. Finally, the draft was pilot-tested with ten patients with advanced cancer who completed the questionnaire and provided feedback through a cognitive debriefing script translated into Malayalam.

Pilot testing

The pilot testing was carried out at the outpatient Department of Cancer Palliative Medicine of Malabar Cancer Centre, a tertiary Cancer Centre in Thalassery in the State of Kerala in South India, between November 2022 and June 2023.

As per the FACIT validation methodology, ten patients were recruited from the outpatient Department of Cancer Palliative Medicine at Malabar Cancer Centre. The participant’s inclusion criteria included: (1) Diagnosis of advanced cancer (defined as metastatic disease or recurrence or progressive disease) and receiving palliative care; (2) 18 years and above; (3) able to read and comprehend Malayalam language and (4) willing to provide informed consent to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Patients with cognitive dysfunction (psychiatric illness and neurological disorders) precluding administration of tool; (2) patients deemed unwell as per the investigator’s clinical assessment, defined as instability in vital signs requiring hospitalisation and/or intensive care unit care.

Procedure

All eligible patients diagnosed with advanced cancer were enrolled in the study after providing the information sheet and getting informed consent. The demographic details such as age, gender, diagnosis, performance status, socioeconomic status, and treatment details were recorded from their case records. The Malayalam translated ‘FACIT Sp-Ex version 4 tool was then administered by the Medical Social Worker who supervised the process. Later, each patient underwent the cognitive debriefing interview, where they were asked questions on an item-by-item basis to restate the item in their own words and to provide interpretations for particular items that were problematic in translation. This process ensured that the meaning intended by the developer was retained in translation and was also understood by the patient in the same way.[30] The interviewer recorded any issues with the understanding or word changes suggested by the patient on the patient information form provided by the FACIT secretariat. The duration of the interviews ranged from 30 to 45 min, of which <10 min were required for most patients to complete the Malayalam version of FACIT-Sp-Ex.

Data analysis

The cognitive debriefing interviews were analysed by the reviewer/language coordinator and FACIT experts. There were multiple harmonised translations of problematic words/sentences as mentioned by the participants. The updated back translations of these harmonised translations were reviewed by the FACIT experts and, in some cases, investigated further until a consensus was reached for each item.

Quantitative variables are presented as mean (± standard deviation [SD]), and qualitative variables as absolute and relative frequencies.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows statistical software version 29.

RESULTS

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

The process of translation and cross cultural adaptation went on smoothly with very few hurdles. For most items, the reconciled Malayalam translation was acceptable by the reviewer/language coordinator and the FACIT team. The Malayalam terms used in three items Sp7, Sp9 and Sp23 when back translated were found to be different from the source. The terms ‘harmony’, ‘faith’, ‘compassion’ and ‘difficulties’ in the original source items when back translated from the Malayalam version became ‘unity’, ‘belief ’ , ‘empathy’ and ‘trouble’ respectively. These issues were discussed between the language coordinator/reviewer and the FACIT team. Following this, the most suitable translation and closest equivalent available in Malayalam was used, and the updated back translation matched the original source term. One other issue solved by the language coordinator was the use of the present continuous tense in the back translation instead of the simple present tense used in the source item.

Pilot testing

A total of ten patients (seven females and three males) participated in the study. The mean age of the participants was 45.90 ± 7.62 years. Eighty per cent of the participants were married, and 50% of them belonged to the upper lower socioeconomic status. Sixty per cent of them lived in a nuclear family, and 70% of them were taken care of primarily by their spouses. Among the patients studied, 50% (n = 5) had breast cancer as their primary diagnosis. Sixty per cent of them were diagnosed as having recurrence, and the remaining were diagnosed as having de novo metastatic disease at the time of their participation in this study. Ninety per cent of the participants were on some form of active palliative anticancer treatment. All patients were aware of the cancer diagnosis, but only 80% of them were aware of the prognosis [Table 2]. The mean spiritual well-being score assessed by the FACIT Sp-Ex version 4 tool was 71.20 (SD = 15.10).

| Sociodemographic and clinical details | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean±S.D | 45.90±7.62 |

| Min-Max | 33–57 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 3 (30) |

| Female | 7 (70) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 8 (80) |

| Unmarried | 2 (20) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 7 (70) |

| Muslim | 1 (10) |

| Christian | 2 (20) |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear family | 6 (60) |

| Joint family | 4 (40) |

| Socioeconomic status (Kuppuswamy scale) | |

| Upper middle | 1 (10) |

| Lower middle | 4 (40) |

| Upper lower | 5 (50) |

| Primary caretaker | |

| Spouse | 7 (70) |

| Children | 1 (10) |

| Other relatives | 2 (20) |

| Site of cancer | |

| Head and neck | 2 (20) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 1 (10) |

| Sarcoma | 1 (10) |

| Breast | 5 (50) |

| Lung | 1 (10) |

| Nature of the advanced disease at the time of study | |

| Metastatic at diagnosis | 4 (40) |

| Recurrent | 6 (60) |

| Aware about the diagnosis | |

| Yes | 10 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) |

| Aware about the prognosis | |

| Yes | 8 (80) |

| No | 2 (20) |

| Education level | |

| Middle school certificate | 1 (10) |

| High school certificate | 4 (40) |

| Intermediate or diploma | 4 (40) |

| Graduate | 1 (10) |

| Performance status | |

| 1 | 1 (10) |

| 2 | 6 (60) |

| 3 | 3 (30) |

| Currently on any palliative anticancer treatment | |

| Yes | 9 (90) |

| No | 1 (10) |

S.D: Standard deviation

Cognitive debriefing interviews

Nine out of the ten participants showed a good understanding of items as the responses they selected corresponded with the reasons they provided for choosing those answers. One participant had difficulty in understanding item Sp20 (‘Throughout the course of my day, I feel a sense of thankfulness for what others bring to my life’) and suggested it be phrased as ‘The happiness I get from the people who talk to me in a day’. After discussion with the other members of the team and with the FACIT team, it was decided to retain the item as the other nine participants had no issues understanding this item.

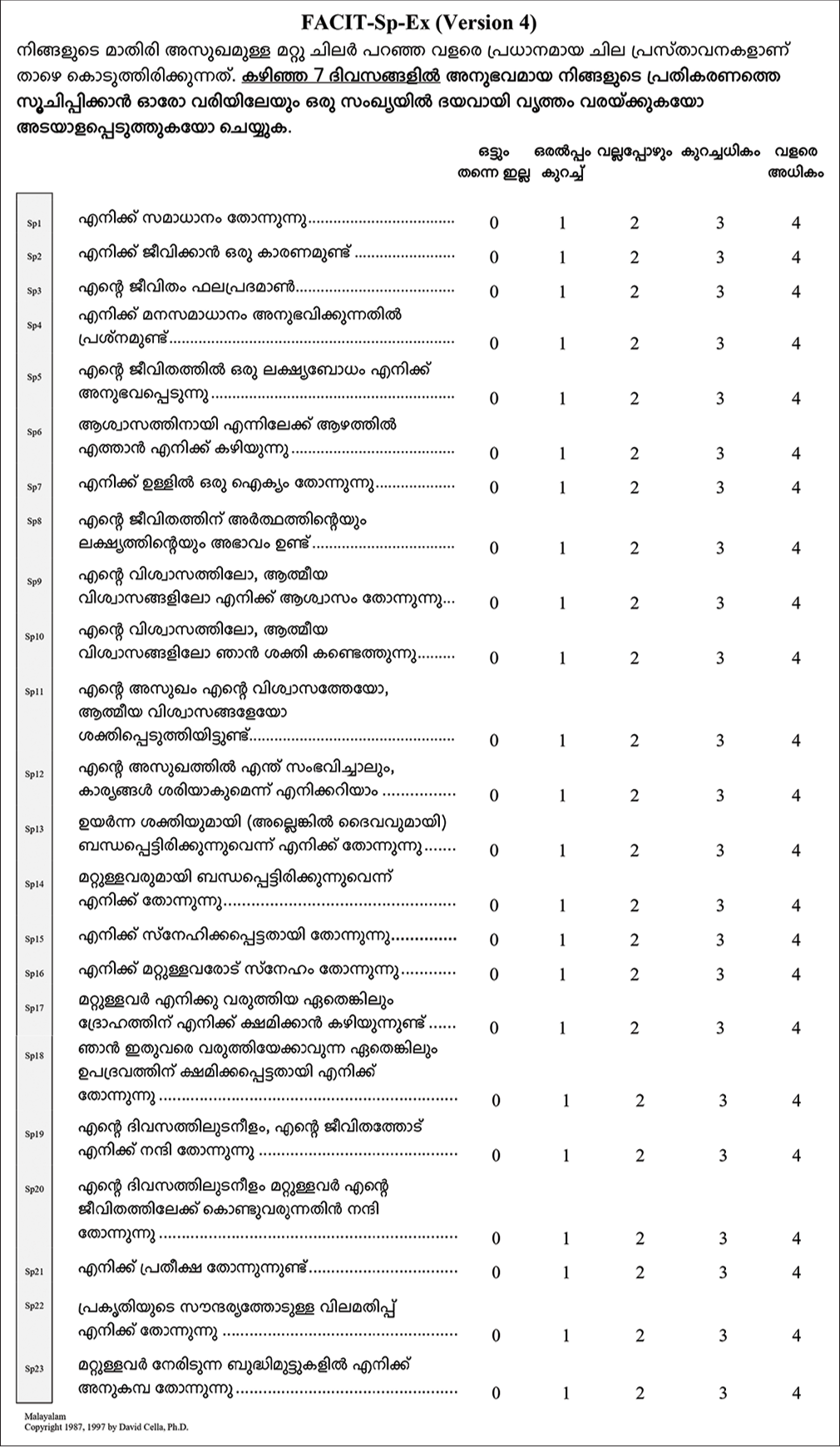

Other than this all the participants found the items in the Malayalam tool relevant, easy to complete with unambiguous and comprehensive response categories. Once all the issues were resolved, a final validated version of the translated tool was created [Figure 3]. This final version was proofread for grammatical, spelling and formatting errors by the reviewer/language coordinator and the entire team.

Finally, the results of the translation and cross-cultural adaptation suggest that the Malayalam translated ‘FACIT-SPEx version 4’ tool is conceptually and semantically equivalent to the English version and is linguistically valid.

- The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual-Well-being-Expanded Malayalam Version.

DISCUSSION

The aim of our study was to translate and cross-culturally adapt the FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 tool into Malayalam and evaluate its linguistic validity. To the best of our knowledge, the FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 is the first linguistically validated tool to assess spiritual well-being in Malayalam speaking people.

A poor translation can result in a tool that does not match the original questionnaire, making it unsuitable for different languages or cultures.[27] To adapt a tool for a new culture, it must be both semantically and conceptually equivalent[33] and this requires careful translation and cultural adaptation.[27] We used the FACIT method, which includes double-back-translation as it is more effective than single translation or translation by committee,[34] followed by the cognitive debriefing in the target population.[30]

In our study, the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation was conducted smoothly, with only the items such as ‘difficulty’, ‘faith’ and ‘harmony’ having back translation problems. These were resolved with discussion within our team and with the FACIT team.

The results of our study indicated that the Malayalam version of FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 is conceptually and semantically equivalent to the English version and linguistically valid.

Limitations of the study

Our study was consistent with FACIT recommendations for pilot testing of a validated tool. A larger sample size of 15– 30 patients would provide greater reliability for our results.

Implications for practice

Spiritual care is an important component of quality palliative care and should be incorporated into the routine care of cancer patients. Our study introduces the Malayalam version of FACIT-Sp-Ex as a valid tool to assess spiritual well-being in advanced cancer patients.

CONCLUSION

Linguistic validation and cognitive debriefing produced the Malayalam translated FACIT-Sp-Ex version 4 tool conceptually equivalent to the original FACIT Sp Ex version 4 tool, and it is feasible for its use.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Harsha Mary Jose and Ms Thulasi Das Nair, the Medical Social Workers, for their contribution to the translation and cross cultural adaptation process and Mr Jason Bredle from the FACIT team for his help during the entire process. The authors also thank all the patients for their participation in the study and their valuable contribution. (This study has been presented in the 31st International conference of Indian Association of Palliative Care held at Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute from 9th to 12th February 2024).

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Malabar Cancer Centre, number 1617/IRB-IEC/13/MCC/October 18, 2022/6, dated 31st October 2022.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- The Relationship of Spiritual Concerns to the Quality of Life of Advanced Cancer Patients: Preliminary Findings. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1022-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- "If God Wanted Me Yesterday, I Wouldn't Be Here Today": Religious and Spiritual Themes in Patients' Experiences of Advanced Cancer. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:581-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Issues in the Care of Dying Patients: ". It's Okay between Me and God" JAMA. 2006;296:1385-92.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines, 4th Edition. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1684-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care: The Report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885-904.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spirituality in the Cancer Trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):49-55.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Role of Spirituality and Religious Coping in the Quality of Life of Patients with Advanced Cancer Receiving Palliative Radiation Therapy. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:81-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Well-being Among Palliative Care Patients With Different Religious Affiliations: A Multicenter Korean Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56:893-901.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Role of Spirituality and Religiosity in Subjective Well-Being of Individuals with Different Religious Status. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1525.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence: Toward a Field of Inquiry. Appl Dev Sci. 2003;7:205-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Well-being of Italian Advanced Cancer Patients in the Home Palliative Care Setting. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017;26

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Spiritual Counseling on Spiritual Well-being in Iranian Women with Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;30:79-84.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between Demographic Characteristics and Spiritual Wellbeing among Cancer Survivors. Belitung Nurs J. 2017;3:405-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Well-being of Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy Through Mindfulness Based Spiritual. Media Keperawatan Indones. 2019;2:83-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Provision of Spiritual Care to Patients with Advanced Cancer: Associations with Medical Care and Quality of Life Near Death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:445-52.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Attention to Inpatients' Religious and spiritual Concerns: Predictors and Association with Patient Satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1265-71.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Why is Spiritual Care Infrequent at the End of Life? Spiritual Care Perceptions among Patients, Nurses, and Physicians and the Role of Training. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:461-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Religion, Spirituality, and Medicine: Psychiatrists' and Other Physicians' Differing Observations, Interpretations, and Clinical Approaches. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1825-31.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An Exploratory Study of Spiritual Care at the End of Life. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:406-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Primary Care Physician Preferences Regarding Spiritual Behavior in Medical Practice. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2751-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Witches' Brew of Spirituality and Medicine. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:74-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An Assessment of US Physicians' Training in Religion, Spirituality, and Medicine. Med Teach. 2011;33:944-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development and Psychometric Assessment of a Spirituality Questionnaire for Indian Palliative Care Patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:9-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Signs of Spiritual Distress and its Implications for Practice in Indian Palliative Care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:306-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being-Expanded (FACIT-Sp-Ex) Across English and Spanish-Speaking Hispanics/Latinos: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2017;9:337-47.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- To Tell or Not to Tell: Exploring the Preferences and Attitudes of Patients and Family Caregivers on Disclosure of a Cancer-Related Diagnosis and Prognosis. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the Process of Cross-cultural Adaptation of Self-report Measures. Spine (PhilaPa 1976). 2000;25:3186-91.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2014. p. :1-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: Properties, Applications, and Interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A Comprehensive Method for the Translation and Cross-cultural Validation of Health Status Questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:212-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Good Practices for the Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Linguistic Validation of Clinician-reported Outcome, Observer-reported Outcome, and Performance Outcome Measures. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4:89.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Measuring Spiritual Well-being in People with Cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49-58.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of Life: From Nursing and Patient Perspectives: Theory, Research, Practice. Vol 36. United States: Jones and Bartlett; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multilingual Translation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Quality of Life Measurement System. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:309-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]