Translate this page into:

Palliative Care Need in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

*Corresponding author: Baridalyne Nongkynrih, Centre for Community Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. baridalyne@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Chandra A, Debnath A, Nongkynrih B. Palliative Care Need in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Indian J Palliat Care 2023;29:375-87.

Abstract

Background:

To achieve sustainable development goal 3.8, countries must prioritise the provision of palliative care. We aimed to estimate the prevalence of palliative care needs in India.

Methods:

A systematic literature search was conducted in databases of PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and EBSCO Host. We included community-based studies published in English between inception and April 30, 2023. We excluded hospital-based studies that were conducted solely including diseased patients. Data were extracted independently, and a quality assessment was performed. To estimate the pooled prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CI), we used the random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic and I2 test. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the study site, urban–rural distribution, gender, and age groups. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot and Egger test. STATA software was used for data analysis.

Results:

Out of the 2632 articles identified, 8 cross-sectional studies were included. Using the random-effects model, the pooled estimate of palliative care needs was found to be 6.21/1000 population (95% CI: 2.42–11.64). The southern region showed a prevalence of 10.83/1000 compared to 2.24/1000 in the northern region. Urban areas had a prevalence of 3.34/1000, while rural areas had a prevalence of 7.69/1000. Among females, the prevalence was 9.64/1000, compared to 6.77/1000 among males. Notably, individuals aged over 60 years had a higher prevalence of palliative care needs, with a rate of 37.86/1000 population.

Conclusion:

This systematic review and meta-analysis highlight a substantial need for palliative care in India, with a prevalence of 6.21 individuals/1000 population.

Keywords

Estimate

Palliation

Supportive care

End of life care

Community

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care is an essential aspect of healthcare that focuses on improving the quality of life of individuals with serious health-related suffering.[1] The World Health Organization defines palliative care as ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering’.[2] Palliative care is an essential element of universal health coverage.[3] Addressing the need for palliative care and pain relief to achieve the target of 3.8 of sustainable development goal.[4] Patients with life-threatening or life-limiting health conditions often experience gaps in continuity of care, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where healthcare systems are frequently overburdened by high demand for services. Community-based palliative care represents a potential solution to address this issue by providing a means to ensure continuity of treatment for individuals with terminal illnesses. Estimating the demand for palliative care is a critical step towards ensuring the provision of quality palliative care services.

Globally, it is estimated that 56.8 million people require palliative care annually, with the majority of adults in need of palliative care and children living in LMICs.[5] This estimation is based on modelling done on data from the Global Burden of Disease Study for 20 diseases plus injury. In India, where the burden of chronic illnesses is high,[6] palliative care services are essential for the provision of holistic care to patients and their families. Several studies in India have reported the need for palliative care in the community setting but varies from 1.5/1,000 population[7] to 43.1/1,000 population.[8] Accurately estimating the need for palliative care and identifying vulnerable groups are crucial steps in prioritising palliative care services and achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3.8. This study aimed to systematically review the existing literature and conduct a meta-analysis to estimate the need for palliative care services in India. By providing an estimation of the need for palliative care services, our study holds the potential to guide the development of targeted policies and improve programmes to address the specific palliative care needs of India.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Research question and selection criteria

Our primary outcome of interest was the need for palliative care among the population of India, which we estimated using summary statistics. Our inclusion criteria involved community-based (population/school-based) studies that assessed the need for palliative care, any study design, conducted in India, studies written or translated to the English language, and published from their inception until the last date of search 30th April 2023. We excluded studies that were conducted solely in hospitals or studies which included only diseased patients to avoid Berksonian bias, we also excluded studies that reported secondary data or review articles or were not conducted on humans.

Search strategy

Two independent authors (AC and AD) conducted the search and independently screened the articles. They evaluated the full-text articles that met the eligibility criteria. In the event of any discrepancies, the authors engaged in discussions to reach a consensus. If they were unable to reach a consensus, the third author (BN) intervened to resolve any outstanding issues. We conducted a comprehensive search for relevant studies by examining various databases including PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and EBSCO Host. We also screened the first 20 pages of Google Scholar. We used keywords such as ‘Palliative care,’ ‘end of life care,’ ‘terminal care,’ ‘hospice care’ and ‘Community,’ ‘Population’ or ‘Cohort,’ and refined our search by incorporating MeSH terms with an asterisk. The detailed search strategy is given in [Annexure 1]. The search strategy was kept broad to increase the sensitivity. In addition, we screened the reference lists of included studies and other reviews to identify any further eligible studies and searched the first 20 pages of Google Scholar. We reached out to four experts to identify any additional studies, and we received responses from two experts. These experts, who hold teaching positions in a renowned medical college and have worked in the field of palliative care within the department of community medicine, provided valuable experience and insights.

Data extraction and data management

A Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet was used to create a final data extraction table for analysis. The table included information such as the author’s name, the study location, the year of publication, the study design, and the number of people requiring palliative care, with a particular emphasis on capturing the proportion of individuals requiring palliative care. Data were independently entered in the data extraction form and were looked for discrepancies. We tried contacting the authors for the incomplete data. To manage the citations and remove duplicates we utilised Mendeley Desktop V1.19.5 software. To independently screen the articles we used the Rayyan application.[9]

Quality assessment

The two independent authors (AC and AD) evaluated the risk of bias using the quality assessment tools recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies. This tool consists of nine questions designed to evaluate various aspects of the study. Based on the number of ‘yes’ responses to these questions, we categorised the studies into different quality levels. Studies were classified as ‘poor’ quality if the number of ‘yes’ responses was less than five, while studies with a number of ‘fair’ responses between 5 and 6 were classified as ‘moderate’ quality. Studies with more than seven ‘good’ responses were considered as ‘high quality’.

Data analysis

The Chi-square-based Q statistic test and I2 test were employed to assess the heterogeneity between the studies, with two-sided P-values. We reported the prevalence of the need for palliative care with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We have used the Freeman–Tukey transformation to adjust for the distribution of the studies. This prevalence was presented as the need for palliative care per 1000 individuals, we used the random effects model based on the DerSimonian and Laird method. To mitigate the risk of bias, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies of poor quality. To assess the source of heterogeneity, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on the study site (Northern part of India vs. Southern part of India), the urban-rural distribution of the study site, gender and age group (<15 years, >15 years and >60 years) of participants with the test of interaction. To assess publication bias, we employed a funnel plot and used the Egger test to evaluate small study effects, with a P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. The meta-analysis was conducted using STATA® software (version 18, STATA Corp).

Reporting

The entire process of literature search, screening, data extraction, systematic review, and meta-analysis was reported using the preferred reporting standard of systematic reviews and meta-analysis flow-chart and meta-analyses of observational studies in the epidemiology checklist to ensure scientific rigour [Annexure 2].

RESULTS

Selection of studies

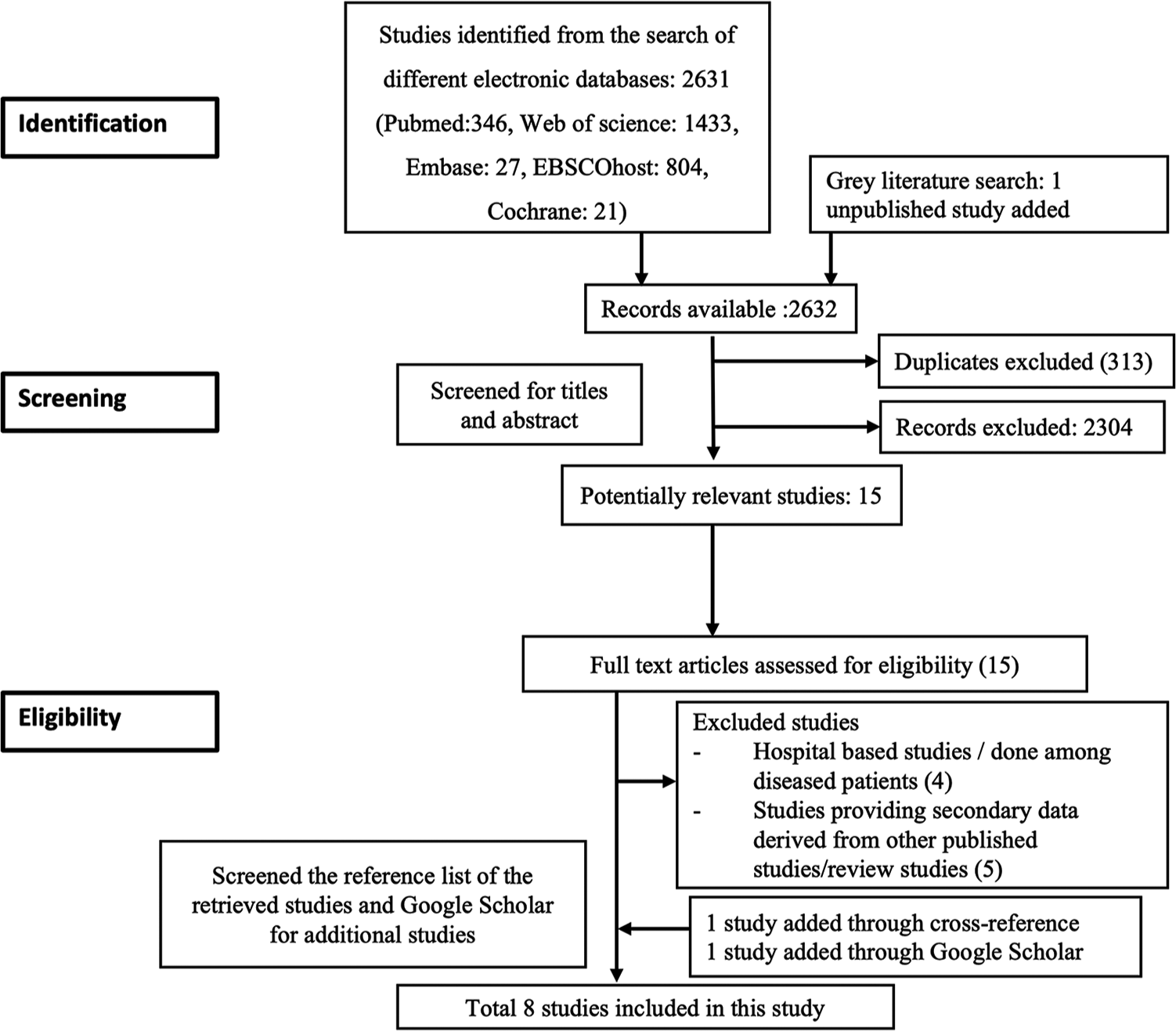

A total of 2632 articles were found in the search. We removed 313 duplicates and screened the remaining 2319 articles for title and abstract. After screening the title and abstract, 2301 articles were deemed ineligible and were excluded. Following the application of eligibility criteria, out of the full text of 15 articles, 9 studies were excluded [ Annexure 3]. Additionally, one study was incorporated through cross-referencing, and another was discovered via Google Scholar. Finally, a total of eight studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis [Figure 1].

- Preferred reporting standard of systematic reviews and meta-analysis flowchart of the search strategy.

Description and quality of the studies

The included studies in this analysis were conducted between 2016 and 2023, employing a cross-sectional research design. In terms of geographical distribution, three were conducted in North India, while the remaining were done in South India. Among the selected studies, five studies were conducted in rural settings, while the other three studies were carried out in urban areas. The majority of the included studies used a 3-item questionnaire to screen for the need for palliative care [Table 1]. One study used a supportive and palliative care indicator tool which has indicators,[8] while another study did not provide details about the methodology.[10] The sample sizes across the studies varied, ranging from 601 to 16,238 individuals. The estimated need for palliative care ranged from 1.5/1,000 population to 43.1/1,000 population. The quality assessment of the studies included in this analysis, of which six were rated as good quality and one study as fair quality [Annexure 4]. One study was found to be of poor quality,[10] which was excluded from the analysis.

| S. No. | Author | Year of publication | Place | Location | Setting | Tool used for identifying the palliative need | Households screened | Sample size (individuals) | Prevalence of palliative care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Chandra et al.[11] | 2016 | Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu | South India | Rural | 3 item structured questionnaire | 145 | 601 | 3.3/1000 |

| 2. | Daya et al.[12] | 2017 | Puducherry | South India | Urban | 3 item structured questionnaire | 1,004 | 3,554 | 6.1/1000 |

| 3. | Elayaperumal et al.[13] | 2018 | Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu | South India | Rural | 3 item structured questionnaire | 1,518 | 7,493 | 4.5/1000 |

| 4. | Kaur et al.[22] | 2020 | Chandigarh | North India | Rural | 3 item structured questionnaire | 884 | 10,021 | 2/1000 |

| 5. | Sudhakaran et al.[8] | 2021 | Karnataka | South India | Rural | SPICT tool | 522 | 2041 | 43.1/1000 |

| 6. | Chandra et al.[7] | 2022 | New Delhi | North India | Urban | 3 item structured questionnaire | 2028 | 16,238 | 1.5/1000 |

| 7. | Gowda et al.[10] | 2022 | Bengaluru, Karnataka | South India | Urban | Not information available | 741 | 2557 | 10.5/1000 |

| 8. | Chandra et al.[14] | 2023 | Haryana | North India | Rural | 3 item structured questionnaire | 1831 | 9727 | 3.7/1000 |

Heterogeneity assessment

The Cochrane q-test indicated heterogeneity (P < 0.01) with I2 = 97.38%. To account for this heterogeneity, a random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird method was employed.

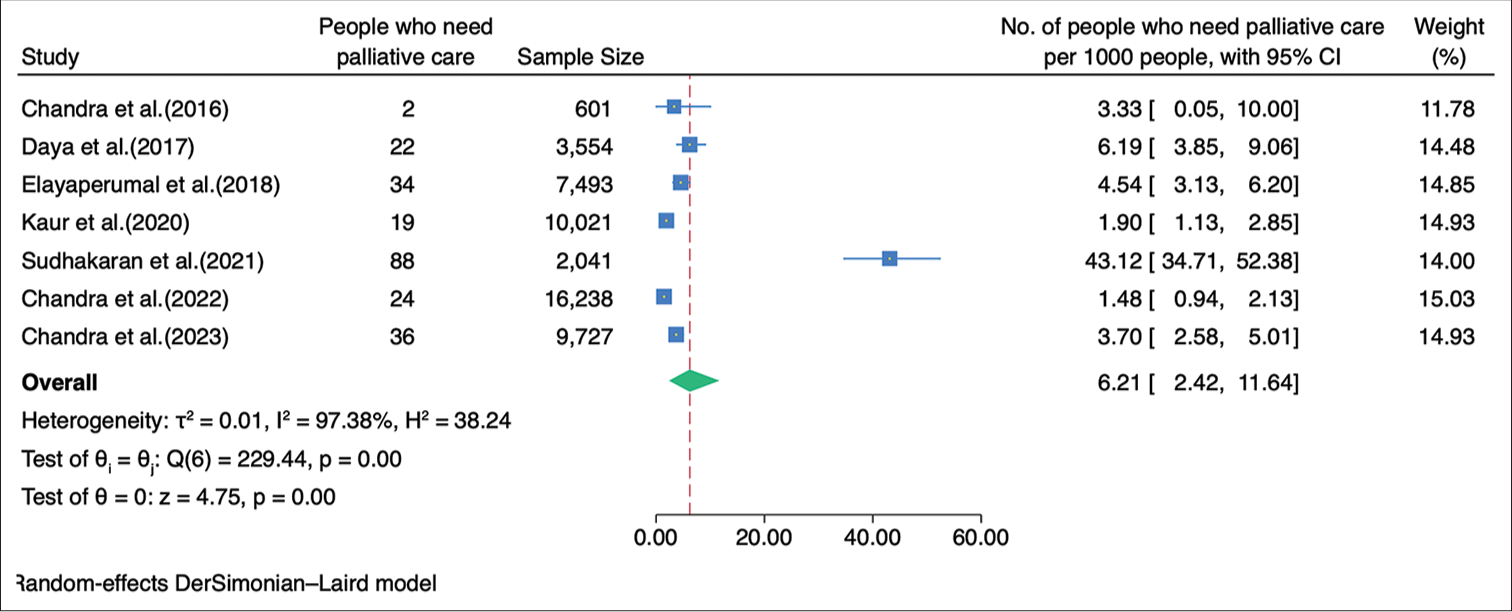

Need estimation in India

A meta-analysis was performed to determine the prevalence of palliative care, using data from 49,675 individuals in the included studies. Among these individuals, 225 were reported to require palliative care. The pooled estimate, obtained through the random-effects model, revealed a prevalence rate of 6.21/1,000 population (95% CI: 2.42–11.64) [Figure 2]. Five studies had provided detailed information regarding the specific diseases or conditions requiring palliative care.[7,11-14] In the details of 118 cases, with 53.4% of these cases being females. The spectrum of diseases encompassed both communicable and non-communicable conditions, as well as curable and non-curable illnesses. Among the identified cases, the most prevalent condition necessitating palliative care was a stroke, accounting for 26.3% of the cases, followed by old age-related weakness, which accounted for 22.9% of the cases and cancer (10.2%) [Annexure 5].

- Forest plot of the meta-analysis for need estimation of palliative care in India.

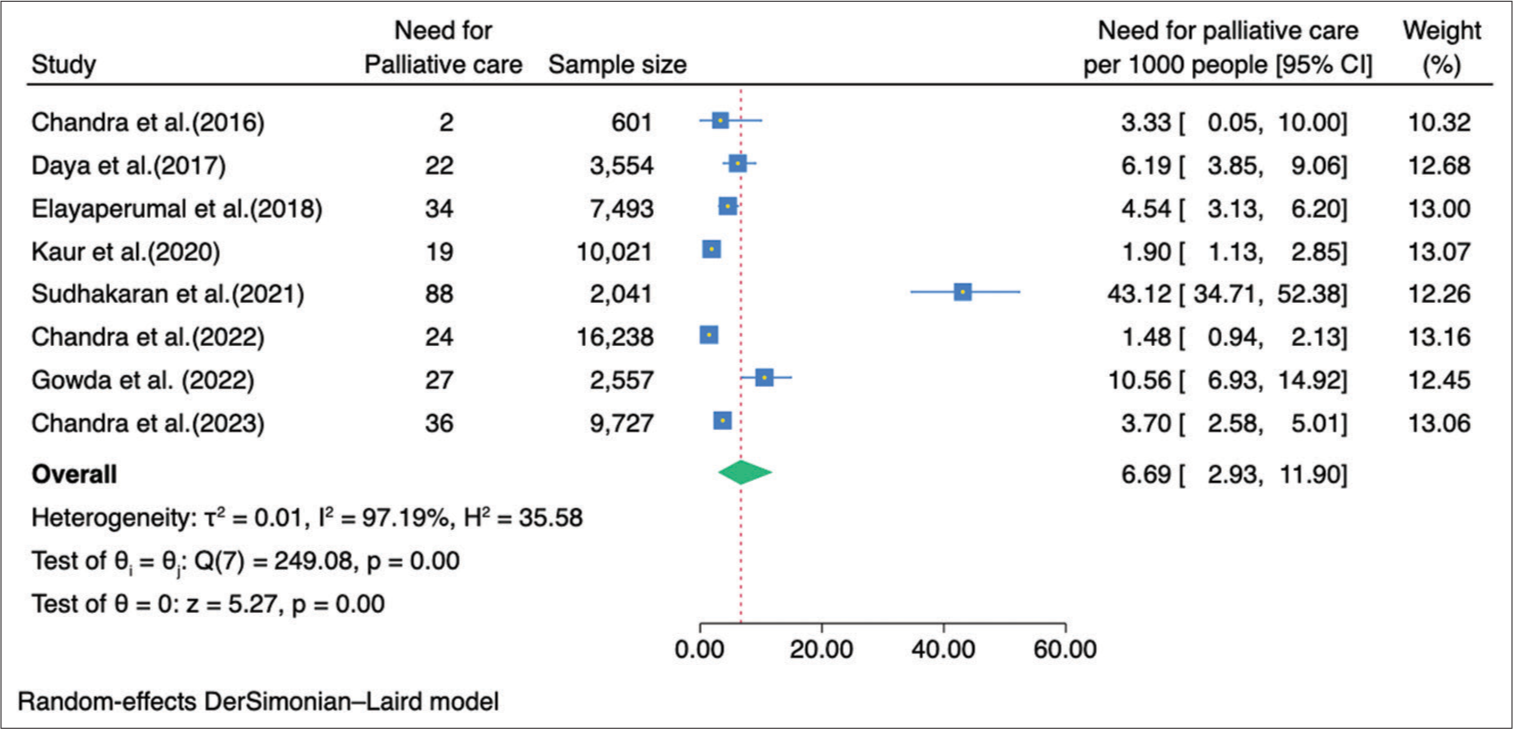

Sensitivity analysis

On adding the excluded study in the analysis, the need of palliative care was found to be 6.69/1,000 population (2.93–11.90) [Annexure 6].

Subgroup analysis

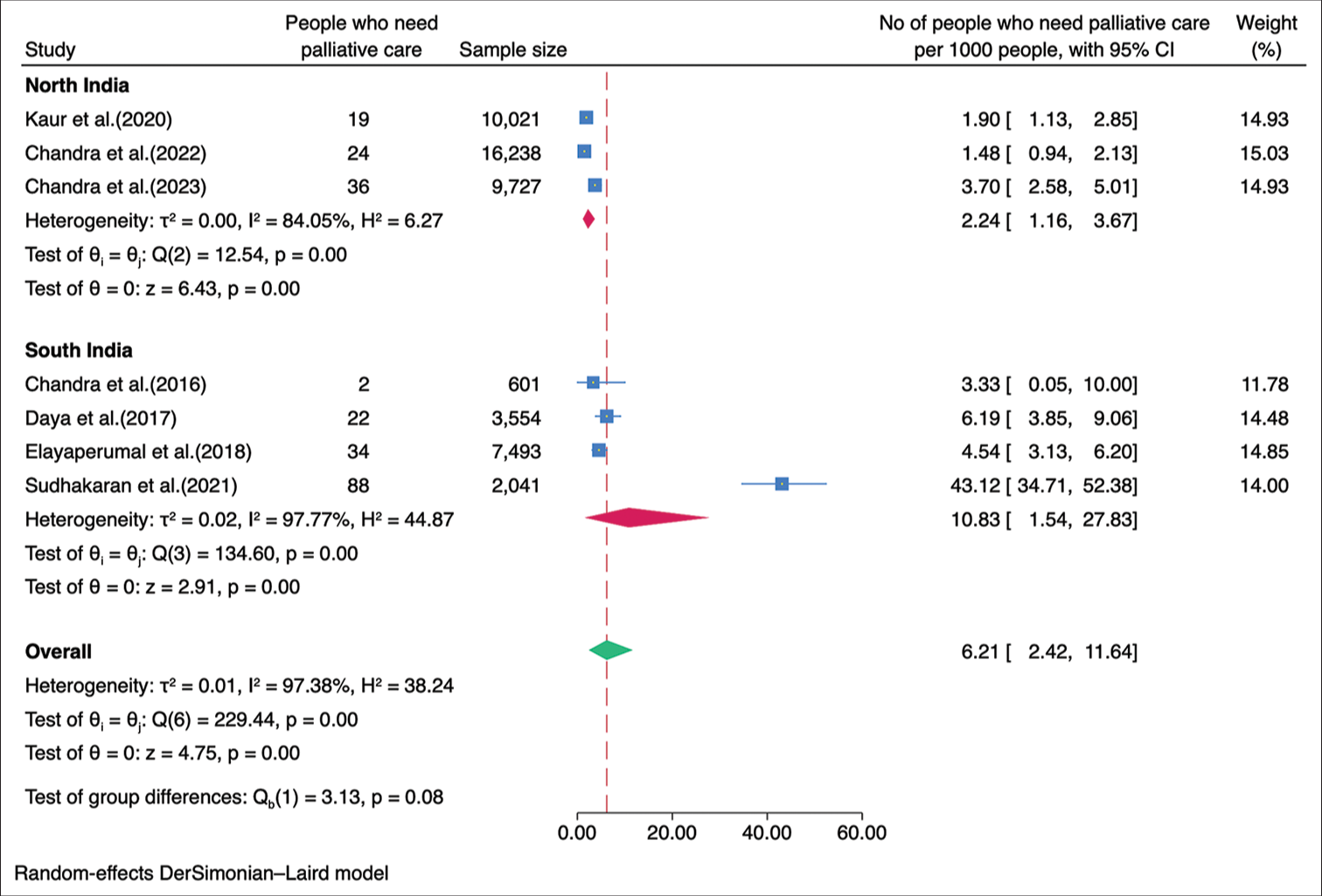

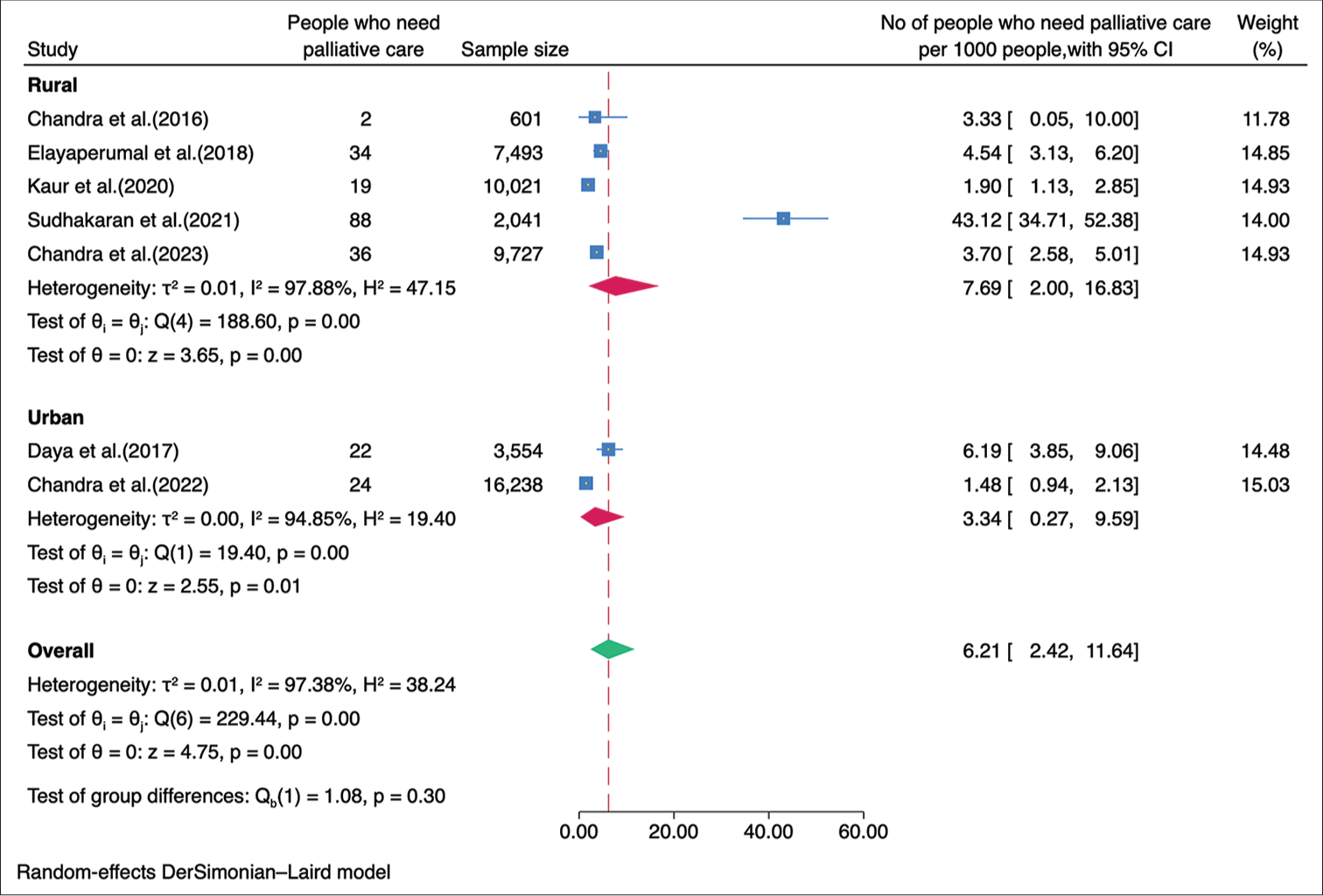

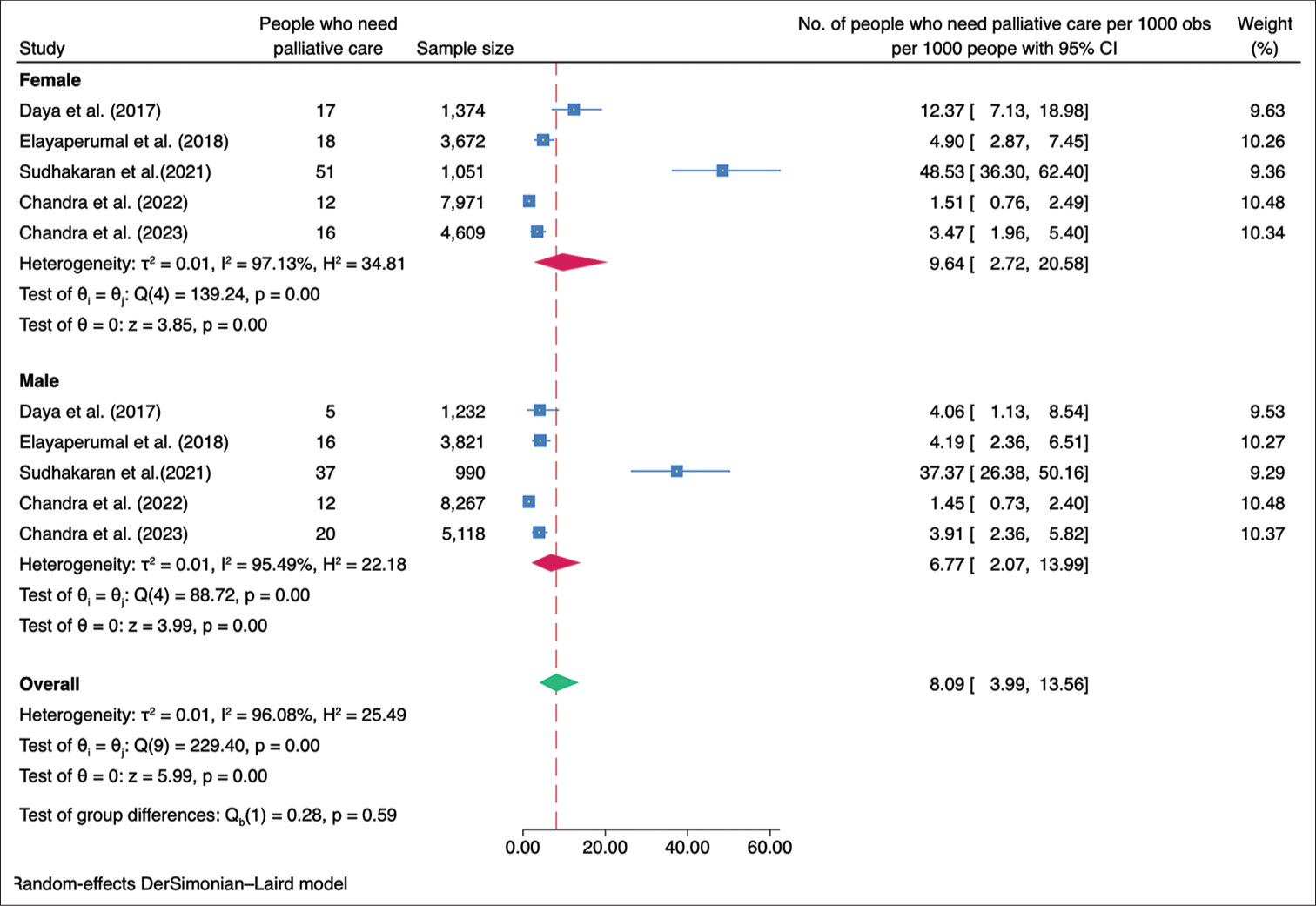

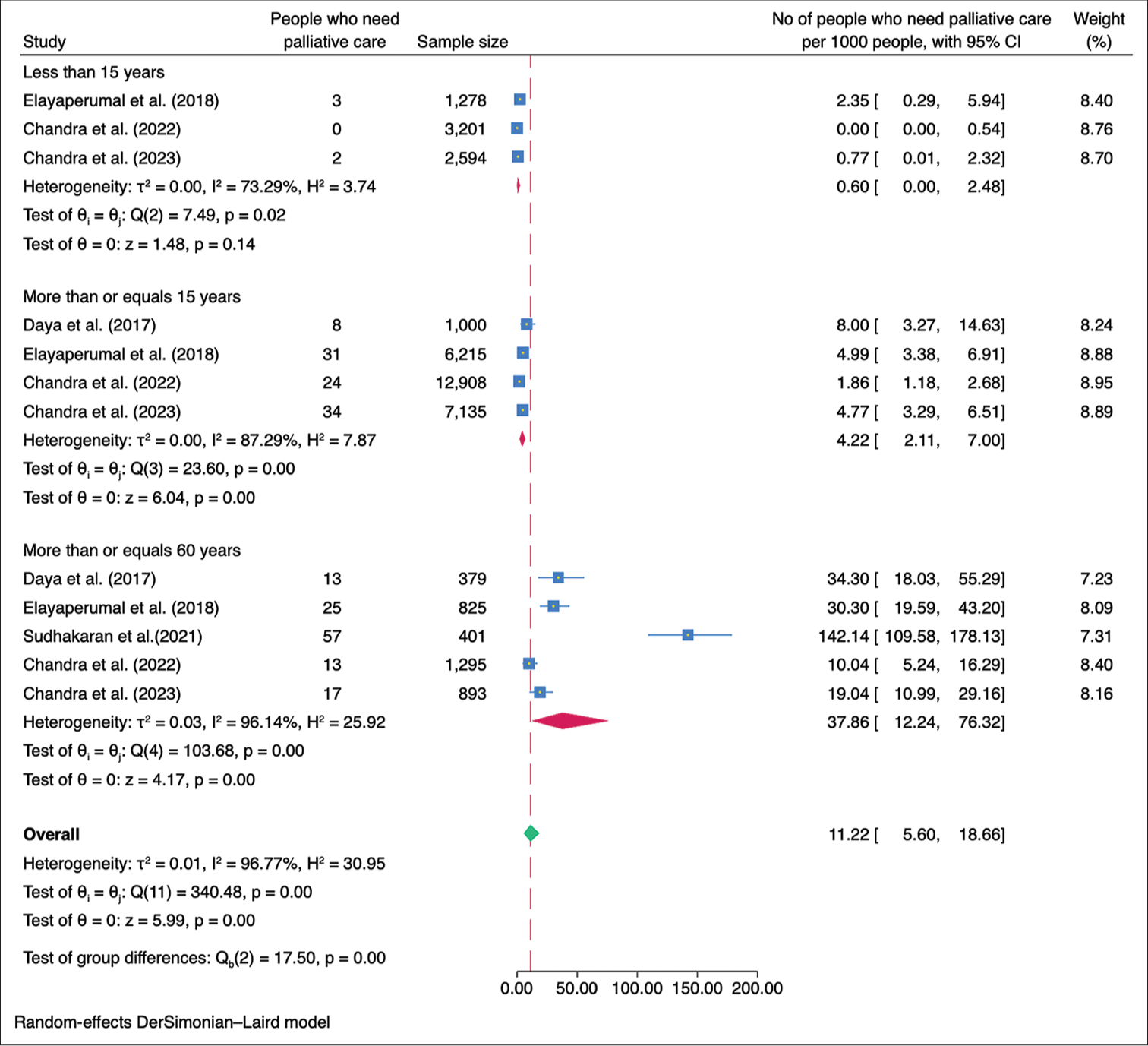

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the geographical location of the studies. The studies were classified into those conducted in the northern and southern regions of India. The combined prevalence of palliative care needs among the studies conducted in the northern region was calculated to be 2.24/1,000 population (95% CI: 1.16–3.67), while the combined prevalence among the studies conducted in the southern region was found to be 10.83/1,000 population (95% CI: 1.54–27.83) [Figure 3]. The need for palliative care in rural areas was 7.69/1,000 population (95% CI 2.00–16.83) while in the urban areas was 3.34/1,000 population (95% CI 0.27–9.59) [Figure 4]. The need for palliative care among females was 9.64/1,000 population (95% CI 2.72–20.58) and among males was 6.77/1,000 population (95% CI 2.07–13.99) [Figure 5]. Moreover, the need for palliative care was found to be highest among participants aged over 60 years, as 37.86/1,000 population (95% CI 12.24–76.32). In contrast, those aged 15 years and more, had a need of 4.22/1,000 population (95% CI 2.11–7.00), while participants under 15 years had a lower need of 0.60/1,000 population (95% CI 0.00–2.48) for palliative care. There was a significant difference in the heterogeneity among the various age groups with I2 of 73.29%, 87.29%, and 96.14% (P < 0.001) [Figure 6].

- Forest plot of the meta-analysis for need estimation of palliative care in India based on the geographical location.

- Forest plot of the meta-analysis for need estimation of palliative care in India based on the urban and rural distribution.

- Forest plot of the meta-analysis for need estimation of palliative care in India based on gender.

- Forest plot of the meta-analysis for need estimation of palliative care in India based on age-groups of the participants.

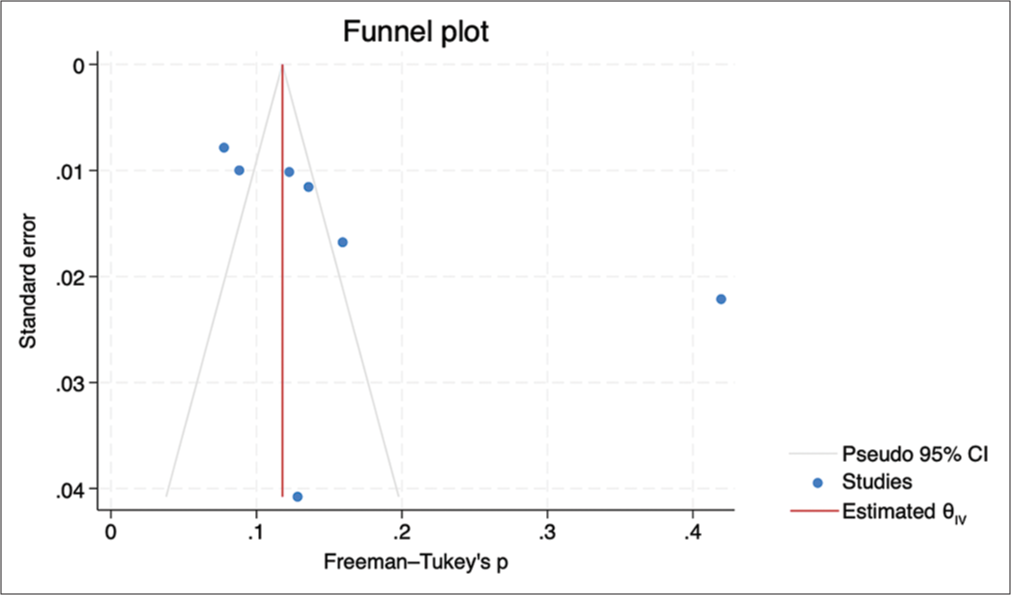

Publication bias

The funnel plot displayed a symmetrical distribution, and the Egger’s test revealed no evidence of small study effects (b = 3.04, P = 0.487) [Figure 7].

- Funnel plot to assess publication bias.

DISCUSSION

The estimated prevalence of palliative care needs in India (6.21/1,000 population) found in this meta-analysis was not affected by the sensitivity analysis. This estimate differs from the estimates reported in studies conducted in various countries.[15-19] These variations in prevalence may be attributed to different methodologies used in estimating the need for palliative care. Some studies rely on secondary data on mortality or disease prevalence, which may not fully capture the spectrum of palliative care needs.[20] In fact, the estimation of the global need for palliative care is primarily based on serious health-related suffering using mortality and prevalence data from the Global Burden of Disease Study. According to this estimation, the global need for palliative care is reported to be 56.8 million/year.[5] Considering a world population of 8 billion,[21] the estimated number of people requiring palliative care translates to 7.1/1,000 population. This estimate is quite similar to our study.

The source of heterogeneity could be due to the various tools used for screening and the difference in the age groups. Subgroup analyses unveiled disparities in palliative care needs concerning geographical location, differentiating between urban and rural areas, as well as gender and older age groups. Recognising the higher need for palliative care among specific populations, such as those residing in rural areas, females, and older adults, targeted interventions should be implemented to address their specific needs. This may involve improving access to palliative care services in rural communities, addressing gender-related barriers, and enhancing support for older adults with life-limiting conditions. Public and healthcare provider awareness regarding the importance and benefits of palliative care should be increased. Educational programs should be implemented to improve healthcare professionals’ knowledge and skills in palliative care, fostering a patient-centred and holistic approach to end-of-life care.

The strength of this study includes a comprehensive search across multiple databases and sources, including contacting experts, to identify relevant studies. We employed specific inclusion criteria, such as community-based studies in India involving the general population, which help ensure the relevance and applicability of the findings to the target population. The use of a standardised quality assessment tool strengthens the rigour of the study by evaluating the risk of bias in the included studies. Subgroup analyses were also conducted to explore variations based on important factors such as study site, urban-rural distribution, gender, and age groups. There were a few limitations of this study. The study only included articles published in English, which may introduce language bias and potentially exclude relevant studies published in other languages. Despite efforts to assess publication bias using a funnel plot and the Egger test, the potential for publication bias cannot be completely ruled out. The study identified high heterogeneity among the included studies. Although a random-effects model was used to account for this heterogeneity, it may still impact the robustness and generalisability of the findings. It is important to note that the geographic distribution of the included studies in this analysis was concentrated in North and South India, which may limit the generalisability of the findings to other regions of the country. We were unable to report the need for palliative care at the household level due to a lack of data limits.

Future research in palliative care should prioritise key areas to enhance understanding and improve services in India. First, developing and validating standardised screening tools for accurately assessing palliative care needs in the general population is crucial. Reliable and comparable data across studies and settings will enable better identification and prioritisation of individuals requiring palliative care. Future studies should aim for diversity and representation by including samples from different regions of India. This will provide a comprehensive understanding of nationwide prevalence, enabling targeted interventions and resource allocation based on regional requirements. Longitudinal studies tracking changes in palliative care needs over time are necessary to identify evolving patterns and trends. Insights from such studies will help healthcare providers and policymakers adapt their strategies accordingly. Targeted interventions for specific population groups, including children, the elderly, and individuals with specific conditions, should be explored to effectively address their unique palliative care needs. Assessing patient outcomes and quality of life is essential to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of palliative care services. Longitudinal research can identify long-term benefits and challenges associated with interventions, while qualitative research provides deeper insights into patient and family experiences, guiding the development of patient-centred and culturally appropriate services. Regular evaluation and monitoring of palliative care programs are crucial for continuous improvement and quality assurance. This involves assessing accessibility, availability, and quality of services across different healthcare settings and regions. It will also help identify barriers and facilitators to effective implementation, informing evidence-based policy decisions and interventions.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the substantial need for palliative care in India. Subgroup analyses indicated a higher prevalence in the southern region, rural areas, among females, and individuals aged 60 years and older. The findings of this study will also provide guidance for healthcare providers and policymakers in the allocation of resources for palliative care services. Future research should focus on developing standardised screening tools, including diverse samples, conducting longitudinal studies, exploring targeted interventions and its outcome, and regularly evaluating and monitoring program implementation.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that they have used artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript or image creations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Alleviating the Access Abyss in Palliative Care and Pain Relief--an Imperative of Universal Health Coverage: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet. 2018;391:1391-454.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Definition of Palliative Care. WHO. Available from: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en [Last accessed on 2019 May 22]

- [Google Scholar]

- Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Fact Sheet. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) [Last accessed on 2023 Apr 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- SDG Target 3.8. Achieve Universal Health Coverage, Including Financial Risk Protection, Access to Quality Essential healthcare services, and Access to Safe, Effective, Quality, and Affordable Essential Medicines and Vaccines for All. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO/sdg-target-3.8-achieve-universal-health-coverage-(uhc)-including-financial-risk-protection [Last accessed on 2023 Apr 04]

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Atlas of Palliative Care. 2020. (2nd ed). Available from: https://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care [Last accessed on 2023 Apr 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- India's Escalating Burden of Non-communicable Diseases. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1262-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimating the Need for Palliative Care in an Urban Resettlement Colony of New Delhi, North India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2022;28:434-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screening for Palliative Care Needs in the Community Using SPICT. Med J Armed Forces India. 2023;79:213-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayyan-A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of Need for Palliative Care in Urban Field Practice Area of Bengaluru-A Cross Sectional Study. RGUHS Natl J Public Health. 2022;7:23-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of Health Awareness Campaign in Improving the Perception of the Community about Palliative Care: A Pre-and Post-intervention Study in Rural Tamil Nadu. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:467-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of Palliative Care Need in the Urban Community of Puducherry. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:81-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identifying People in Need of Palliative Care Services in Rural Tamil Nadu: A Survey. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:393-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing Awareness and Palliative Care Needs in Rural Haryana, North India: A Community-Based Study. Cureus. 2023;15:e47052.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Need for Palliative Care in Ireland: A Population-Based Estimate of Palliative Care Using Routine Mortality Data, Inclusive of Nonmalignant Conditions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:726-33.e1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Size of the Population Potentially in Need of Palliative Care in Germany-an Estimation Based on Death Registration Data. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:29.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of the Demand for Palliative Care in non-oncologic Patients in Chile. BMC Palliat Care. 2023;22:5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimating the Need for Palliative Care at the Population Level: A Cross-national Study in 12 Countries. Palliat Med. 2017;31:526-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How Many People Need Palliative Care? A Study Developing and Comparing Methods for Population-based Estimates. Palliat Med. 2014;28:49-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issues using Linkage of Hospital Records and Death Certificate Data to Determine the Size of a Potential Palliative Care Population. Palliat Med. 2017;31:537-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/swp2023 [Last accessed on 2023 Apr 25]

- [Google Scholar]

- Need of Palliative Care Services in Rural Area of Northern India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020;26:528-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SUPPLEMENTARY FILE

| PubMed | ||

| #1 | ‘Community’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘Population’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘Cohort’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘Group’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘people’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘adult*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘patient*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘child*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘elder*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘adolescen*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘Young’[Title/Abstract] | 13,067,224 |

| #2 | ‘Need’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘Demand’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘requir*’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘estimat*’[Title/Abstract] | 4,553,110 |

| #3 | ‘palliative care’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘end of life care’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘palliative medicine’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘terminal care’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘hospice care’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘Palliative’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘support care’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘advance care’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘palliative care’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘terminal care’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘hospice care’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘palliative medicine’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘palliative care’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘nursing care’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘serious health related suffering’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘life limiting illness’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘life threatening disease’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘terminally ill’[Title/Abstract] | 293,253 |

| #4 | ‘india*’[Title/Abstract] | 203,310 |

| #5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 | 346 |

| EMBASE | ||

| #1 | community OR population OR cohort OR group OR people OR ‘adult’/exp OR ‘adult’ OR ‘adults’ OR ‘grown-ups’ OR ‘grownup’ OR ‘grownups’ OR ‘patient’/exp OR ‘child’/exp OR ‘child’ OR ‘children’ OR young OR ‘aged’/exp OR ‘aged’ OR ‘aged patient’ OR ‘aged people’ OR ‘aged person’ OR ‘aged subject’ OR ‘elderly’ OR ‘elderly patient’ OR ‘elderly people’ OR ‘elderly person’ OR ‘elderly subject’ OR ‘senior citizen’ OR ‘senium’ | 20,889,924 |

| #2 | ‘need’/exp OR estimate OR ‘demand’/exp OR requirement) AND ‘India’/exp | 711,146 |

| #3 | end of life care’ OR ‘palliative therapy’/exp OR ‘palliation’ OR ‘palliative care’ OR ‘palliative consultation’ OR ‘palliative medicine’ OR ‘palliative radiotherapy’ OR ‘palliative surgery’ OR ‘palliative therapy’ OR ‘palliative treatment’ OR ‘symptomatic treatment’ OR ‘terminal care’ OR ‘hospice care’ OR palliative OR ‘support care’ OR ‘advance care planning’/exp OR ‘nursing care’ OR ‘serious health-related suffering’ OR ‘life limiting illness’ OR ‘life threatening disease’ OR ‘terminally ill patient’/exp | 350,069 |

| #4 | India | 188,386 |

| #5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 | 27 |

| Web of Science | ||

| #1 | TS=(Community OR Population OR Cohort OR Group OR people OR adult* OR patient* OR child* OR elder* OR adolescent* OR Young) | 14538067 |

| #2 | TS=(Need OR Demand OR require* OR estimate*) | 7721864 |

| #3 | TS=(palliative care OR end of life care OR palliative medicine OR terminal care OR hospice care OR Palliative OR support care OR advance care OR palliative care OR terminal care OR hospice care OR palliative medicine OR palliative care OR nursing care OR serious health related suffering OR life-limiting illness OR life threatening disease OR terminally ill) | 497187 |

| #4 | TS=(India) | 208327 |

| #5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 | 1433 |

| EBSCOHost-Academic Search Complete | ||

| #1 | TX ‘Community’ OR TX ‘Population’ OR TX ‘Cohort’ OR TX ‘Group’ OR TX ‘people’ OR TX ‘adult*’ OR TX ‘patient*’ OR TX ‘child*’ OR TX ‘elder*’ OR TX ‘adolescent*’ OR TX ‘Young’ | 383493 |

| #2 | TX ‘Need’ OR TX ‘Demand’ OR TX ‘require*’ OR TX ‘estimate*’ | 238,551 |

| #3 | TX ‘palliative care’ OR TX ‘end of life care’ OR TX ‘palliative medicine’ OR TX ‘terminal care’ OR TX ‘hospice care’ OR TX ‘Palliative’ OR TX ‘support care’ OR TX ‘advance care’ OR TX ‘terminal care’ OR TX ‘serious health related suffering’ OR TX ‘life limiting illness’ OR TX ‘life threatening disease’ OR TX ‘terminally ill’ | 3722 |

| #4 | TX ‘India*’ | 71397 |

| #5 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 | 804 |

| Cochrane | ||

| #1 | (Community):ti, ab, kw OR (Population):ti, ab, kw OR (Cohort):ti, ab, kw OR (Group):ti, ab, kw OR (people):ti, ab, kw OR (adult*):ti, ab, kw OR (child*):ti, ab, kw OR (elder*):ti, ab, kw OR (adolescen*):ti, ab, kw OR (Young*):ti, ab, kw | 1371409 |

| #2 | (Need):ti, ab, kw OR (Demand):ti, ab, kw OR (requir*):ti, ab, kw OR (estimat*):ti, ab, kw | 337591 |

| Cochrane | ||

| #3 | (‘palliative care): ti, ab, kw OR (‘end of life care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘palliative medicine’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘terminal care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘hospice care’):ti, ab, kw OR (Palliative):ti, ab, kw OR (‘support care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘advance care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘palliative care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘terminal care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘hospice care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘palliative medicine’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘nursing care’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘serious health related suffering’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘life limiting illness’):ti, ab, kw OR (‘terminally ill’):ti, ab, kw | 13430 |

| #4 | (India):ti, ab, kw | 10666 |

| #5 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 | 21 |

| Topic | Page number | |

| Title | Identify the study as a meta-analysis (or systematic review) | 1 |

| Abstract | Use the journal’s structured format Introduction | 1 |

| Introduction | The clinical problem | 2 |

| The hypothesis | 2 | |

| A statement of objectives that includes the study population, the condition of interest, the exposure or intervention, and the outcome (s) considered | 2 | |

| Sources | Qualifications of searchers (e.g., librarians and investigators) | 3 |

| Search strategy, including the time period included in the synthesis and keywords | 3 | |

| Effort to include all available studies, including contact with authors | 3 | |

| Databases and registries searched | 3 | |

| Search software used, name and version, including special features used (e.g. explosion) | 4 | |

| Use of hand searching (e.g., reference lists of obtained articles) | 3 | |

| List of citations located and those excluded, including justification | 4 | |

| Method of addressing articles published in languages other than English | NA | |

| Method of handling abstracts and unpublished studies | 3 | |

| Description of any contact with authors | 3 | |

| Study Selection | Types of study designs considered | 3 |

| Relevance or appropriateness of studies gathered for assessing the hypothesis to be tested | 3 | |

| Rationale for the selection and coding of data (e.g., sound clinical principles or convenience) | 3 | |

| Documentation of how data were classified and coded (e.g., multiple raters, blinding, and inter-rater reliability) | 3 | |

| Assessment of confounding (e.g. comparability of cases and controls in studies where appropriate) | NA | |

| Assessment of study quality, including blinding of quality assessors; stratification or regression on possible predictors of study results | 4 | |

| Assessment of heterogeneity | 4 | |

| Statistical methods (e.g. complete description of fixed or random effects models, justification of whether the chosen models account for predictors of study results, dose-response models, or cumulative meta-analysis) in sufficient detail to be replicated | 4 | |

| Results | A graph summarising individual study estimates and the overall estimate | Figure 2 |

| A table giving descriptive information for each included study | Table 1 | |

| Results of sensitivity testing (e.g. subgroup analysis) | Supplementary file | |

| Indication of statistical uncertainty of finding | 4 | |

| Discussion | Strengths and weakness | 13 |

| Potential biases in the review process (e.g. publication bias) | Figure 7 | |

| Assessment of quality of included studies | 7 | |

| Consideration of alternative explanations for observed results | 12 | |

| Generalisation of the conclusions (i.e. appropriate for the data presented and within the domain of the literature review) | 13 | |

| Guidelines for future research | 13 | |

| Disclosure of funding source | ||

Annexure 3: List of articles excluded in eligibility screening.

Review studies/secondary data

Philip RR, Philip S, Tripathy JP, Manima A, Venables E. Twenty years of home-based palliative care in Malappuram, Kerala, India: a descriptive study of patients and their care-givers. BMC palliative care. 2018 Dec;17(1):1-9. Nambiar AR, Rana S, Rajagopal MR. Serious health-related suffering and palliative care in South Asian countries. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2021 Sep 1;15(3):169-173. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000565. PMID: 34292186. Krishnan A, Rajagopal MR, Karim S, Sullivan R, Booth CM. Palliative Care Program Development in a Low- to Middle-Income Country: Delivery of Care by a Nongovernmental Organization in India. J Glob Oncol. 2018 Sep;4:1-8. doi: 10.1200/JGO.17.00168. PMID: 30241254; PMCID: PMC6223464. Kar, SS; Subitha, L; Iswarya, S. Palliative care in India: Situation assessment and future scope. Indian Journal of Cancer 52(1):p 99-101, Jan–Mar 2015. | DOI: 10.4103/0019-509X.175578 Ghoshal A, Joad AK, Spruijt O, Nair S, Rajagopal MR, Patel F, Damani A, Deodhar J, Goswami D, Joshi G, Butola S. Situational analysis of the quality of palliative care services across India: a cross-sectional survey.

Among diseases population/hospital based

Lithin Z, Thomas PT, Warrier GM, Bhaskar A, Nashi S, Vengalil S, et al. Palliative Care Needs and Care Giver Burden in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Cross Sectional Study. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2020;23:313-7. Prasad P, Sarkar S, Dubashi B, Adinarayanan S. Estimation of Need for Palliative Care among Noncancer Patients Attending a Tertiary Care Hospital. Indian J Palliat Care 2017;23:403-8. Gupta M, Sahi MS, Bhargava AK, Talwar V. A Prospective Evaluation of Symptom Prevalence and Overall Symptom Burden among Cohort of Critically Ill Cancer Patients. Indian J Palliat Care 2016;22:118-24. Mahendru K, Gupta N, Soneja M, Malhotra RK, Kumar V, Garg R, et al. Need for Palliative Care in Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Cross-sectional Observational Study. Indian J Palliat Care 2021;27:275-80.

| S.No. | Author | Year of publication | 1. Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population? | 2. Were study participants sampled in an appropriate way? | 3. Was the sample size adequate? | 4. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | 5. Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? | 6. Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition? | 7. Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? | 8. Was there appropriate statistical analysis? | 9. Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately? | Total number of ‘yes’ | Overall appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Chandra et al.[11] | 2016 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/9 (Good) | Include |

| 2. | Daya et al.[12] | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 (Good) | Include |

| 3. | Elayaperumal et al.[13] | 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | 7/9 (Good) | Include |

| 4. | Kaur et al.[22] | 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | 5/9 (Fair) | Include |

| 5. | Sudhakaran et al.[8] | 2021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | 8/9 (Good) | Include |

| 6. | Chandra et al.[7] | 2022 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 (Good) | Include |

| 7. | Gowda et al.[10] | 2022 | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | 2/9 (Poor) | Exclude |

| 8. | Chandra et al.[14] | 2023 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9/9 (Good) | Include |

| Disease condition | Male | Female | Total | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | 19 | 12 | 31 | 26.3% |

| Old age related weakness | 8 | 19 | 27 | 22.9% |

| Cancer | 5 | 7 | 12 | 10.2% |

| Fracture | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6.8% |

| Mental retardation/Intellectual disability | 1 | 4 | 6 | 5.1% |

| Congenital anomaly/Childhood disability/Polio | 2 | 4 | 6 | 5.1% |

| Heart disease | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4.2% |

| Osteoarthritis with marked dependence | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4.2% |

| Spinal injury/trauma | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3.4% |

| HIV | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3.4% |

| CKD | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2.5% |

| Severe COPD | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.7% |

| Diabetic foot | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.8% |

| Filariasis | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.8% |

| Psychosis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.8% |

| Tuberculosis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.8% |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.8% |

| Total | 54 | 63 | 118 | 100% |

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, CKD: Chronic kidney disease, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Forest plot of meta-analysis of need for palliative care in community in India based on eight studies.