Translate this page into:

Palliative Care Services in Bhutan: Current Progress and Future Needs

*Corresponding author: Namkha Dorji, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital, Thimphu, Bhutan. namji2002@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Dorji N, Yangden Y, Bhuti K, Dorjey Y, Tshering S, Giam CL, et al. Palliative Care Services in Bhutan: Current Progress and Future Needs. Indian J Palliat Care. 2025;31:79-85. doi: 10.25259/IJPC_206_2024

Abstract

Palliative care (PC) is a young concept in Bhutan. Since the establishment of home-based PC services at the national referral hospital of Bhutan for the residents of Thimphu City in 2018, many patients have benefitted. The need for PC in Bhutan is huge and urgent. The provision of quality PC is important to improve the quality of life of people facing life-limiting illnesses and end-of-life care, irrespective of their diagnosis. At present, efforts are being made to expand the services to the rest of the country by developing human resources. The plan is to train the existing manpower with the help of regional and international experts so that the PC services in Bhutan are sustainable.

Keywords

End-of-life care

Life-limiting illness

Palliative care

INTRODUCTION

With an ageing population and increasing noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in the world, Bhutan is no exception to experiencing a shift in the disease pattern from communicable to NCDs. The prevalence of life-limiting illnesses is increasing in Bhutan, with an ever-increasing need for palliative care (PC) services. PC is an active, holistic care of patients of all ages and their families facing serious health-related suffering. It aims to improve their quality of life throughout the illness trajectory, at end-of-life and beyond, as grief and bereavement support.[1]

In the global health scenario, inequality of access to PC is one of the major disparities,[2] particularly in the low and middle-income countries (LMICs). One of the major barriers is a misunderstanding of what constitutes PC; in particular, it is not always understood that PC is beyond just the care for the dying and that it is not an alternative to disease prevention and treatment but an integral part of the management.[3]

Bhutan is a small LMIC in the eastern Himalayas surrounded by India in the east, south and west and China in the north, with a projected population of 763,249 in 2022.[4] The life expectancy at birth (years) has improved to 73.1 years in 2019 from 65.7 years in 2000.[5] The constitution of Bhutan mandates free basic healthcare services for the Bhutanese people.[6] Healthcare services in Bhutan are a three-tiered approach with primary, secondary and tertiary levels.[7] In Bhutan, traditional medicine services and allopathic medicine services are integrated, and patients are referred between the two services.[8]

With its increasing trend, more than half of deaths in Bhutan are caused by NCDs.[9] A total of 941 patients (477 males and 464 females), including children, died from cancers between 2014 and 2018 in Bhutan, with stomach cancer and cervical cancer as the leading cause of death in males and females, respectively.[10] Hence, there is an immense need for PC services across Bhutan.

HISTORY OF PC IN BHUTAN

The concept of PC in Bhutan is relatively new. It all began in 2016 when two of the lecturers (TDL was one of them) from the Faculty of Nursing and Public Health, Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan, travelled to Kerala in India and attended a 6-week hands-on training on PC at Pallium India, a World Health Organization (WHO) collaborating Centre.[11] Upon their return, they made a few sensitisation presentations about PC and its benefits amongst relevant stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health (MoH), Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH) and the Bhutan Cancer Society (BCS). After that, more nurses were sent to Kerala for the same training. With the rising number of patients diagnosed with cancers and presenting at the advanced stages with the limited scope of curative treatment, the JDWNRH management envisioned starting the home-based PC services. In February 2018, a proposal was submitted to the MoH to start home PC for cancer patients residing within the capital city, Thimphu. This marked the initial step towards introducing a crucial service to cater to the PC needs of patients. Moving forwards, from March to June 2018, the programme entered a pilot phase, with three dedicated nurses at the helm, initially supported by the only surgical oncologist and a nurse anaesthetist. The successful completion of the pilot phase culminated in the submission of a comprehensive report to the MoH outlining the feasibility and effectiveness of the home-based PC service in JDWNRH.

The goals of home PC were to care for patients and families in their homes, add dignity and value at the end of life, reduce overcrowding and bed shortages at the hospital and achieve cost-effectiveness in terms of hospitalisation and health-care resource utilisation.[12] It also aimed to re-instil the sense of beauty, purpose and value of life for the people affected by life-limiting illnesses, especially with cancer, enabling patient-and-family-focused care and maximising quality time spent with their loved ones as they traverse the most harrowing journey in life. Above all, the home-based PC programme endeavours to honour every Bhutanese at the end of their lives with compassionate care and the best possible support in line with the cultural and societal norms of Bhutan.[12]

December 2018 proved to be a pivotal moment when a High-Level Committee meeting presided over by Her Royal Highness (HRH) Ashi (Princess) Kesang Wangmo Wangchuck convened at the MoH. This meeting sought and secured crucial approval for the official launching of the PC service. Moving ahead, a collaboration with the WHO Collaborating Centre at the Institute of Palliative Medicine (IPM) unfolded in September-December 2020. Under the guidance of the WHO South-East Asia Region (WHO SEARO), this partnership resulted in the creation of a comprehensive training manual on PC for Bhutanese health workers, which transitioned to an online platform due to COVID-19 travel restrictions.

In November 2020, another significant milestone was witnessed with the official launch of the integration of the Traditional Medicine Department (TMD) into PC, which was also presided over by HRH Ashi Kesang Wangmo Wangchuck and the Health Minister.[13]

Today, the Home PC Unit is manned by a PC physician and four dedicated nurses. A nurse anaesthetist, specialised in pain management, also accompanies the team on a weekly basis.

ACTIVITIES OF HOME PC TEAM

The main activities carried out during home visits are nursing assessment and procedures, pain and symptoms management, medicine compliance assessment and medicine refill, education and counselling for patients and families, assessment and assistance of socioeconomic needs, assistive devices, help in obtaining death certification, telephonic consultation services round the clock, continuing medical education for nurses and networking services. A study by Lewis et al. found that the virtual conference was found to have a role in providing PC services for those patients who have an established relationship with health professionals.[14] Since the joining of PC physicians recently, PC services have been provided in the wards of JDWNRH. However, there is no separate PC ward.

OUTCOMES OF HOME PC SERVICES BETWEEN 2018 AND 2024

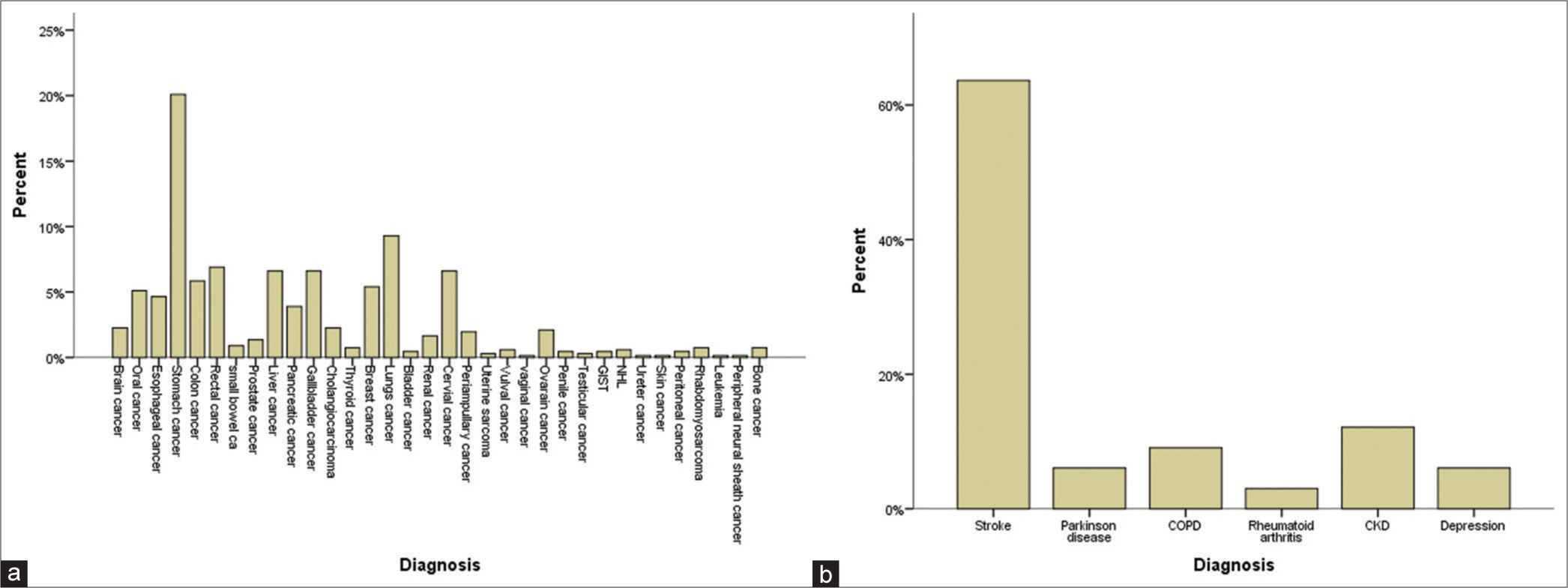

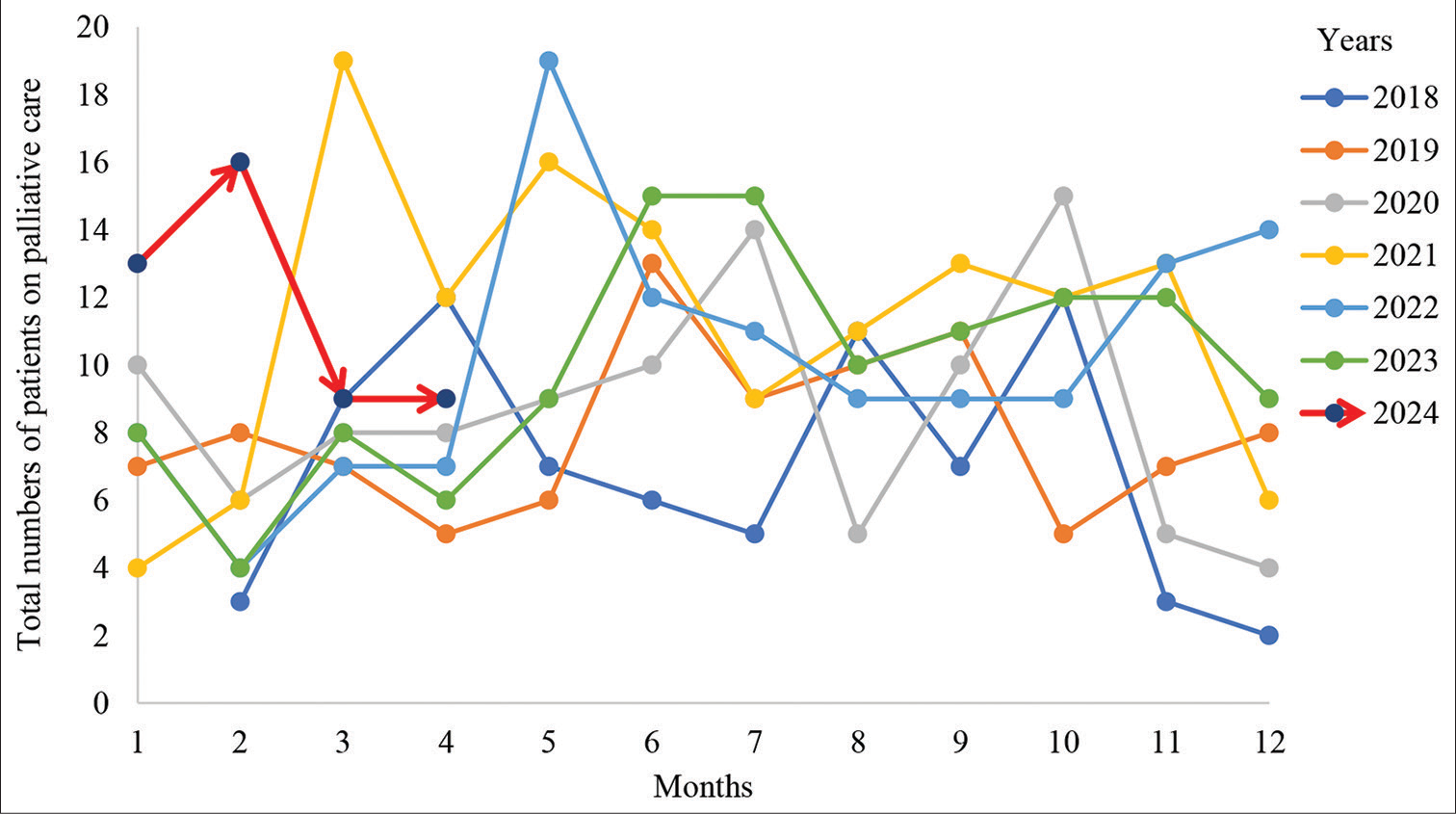

We have reviewed the details of patients catered to by home PC services between 2018 and April 2024 maintained in the PC Unit, JDWNRH. A total of 710 patients, 319 females (44.9%) and 391 males (55.1%), have received the care [Table 1]. The majority of them were cancer patients, and those with non-cancer conditions had stroke, Parkinson’s disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease and depression [Table 2]. Amongst cancer cases, patients with stomach cancer constituted the highest number (134, 20%) [Figure 1a], and stroke represented the highest amongst the non-cancer cases (31, 63.6%) [Figure 1b]. The monthly distribution of patient load is shown in Figure 2.

| Years | Total, n(%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 33 | 46 | 49 | 63 | 58 | 53 | 17 | 319 (44.9) |

| Female | 44 | 51 | 55 | 73 | 67 | 70 | 31 | 391 (55.1) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| Mean | ||||||||

| (min–max) | 62.1 (24–87) | 64.8 (11–89) | 61.9 (20–91) | 64.9 (14–96) | 65.3 (19–94) | 64.9 (3–94) | 64.7 (32–93) | |

| Districts | ||||||||

| Thimphu | 5 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 23 | 17 | 5 | 91 (12.8) |

| Tashigang | 8 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 69 (9.7) |

| Punakha | 5 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 43 (6.1) |

| Samtse | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 39 (5.9) |

| Wangdi | 5 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 39 (5.5) |

| Dagana | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 36 (5.1) |

| Pemagatshel | 6 | 3 | 7 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 36 (5.1) |

| Chukha | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 34 (4.8) |

| Mongar | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 33 (4.6) |

| Tsirang | 2 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 30 (4.2) |

| Sarpang | 3 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 30 (4.2) |

| Bumthang | 4 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 29 (4.1) |

| Samdrupjongkhar | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 27 (3.8) |

| Paro | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 27 (3.8) |

| Trongsa | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 27 (3.8) |

| Lhuntse | 3 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 26 (3.7) |

| Tashiyangtse | 1 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 25 (3.5) |

| Zhemgang | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 21 (2.9) |

| Haa | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 17 (2.4) |

JDWNRH: Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital

| Diagnosis | Years | Total, n(%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Cancer | ||||||||

| Brain cancer | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 15 (2.2) |

| Oral cancer | 1 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 34 (5.1) |

| Oesophageal cancer | 2 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 31 (4.6) |

| Stomach cancer | 20 | 14 | 21 | 32 | 25 | 15 | 7 | 134 (20.0) |

| Colon cancer | 4 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 39 (5.8) |

| Rectal cancer | 7 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 46 (6.8) |

| Small bowel cancer | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 (0.9) |

| Prostate cancer | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9 (1.3) |

| Liver cancer | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 44 (6.5) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 26 (3.8) |

| Gallbladder cancer | 7 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 44 (6.6) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 15 (2.2) |

| Thyroid cancer | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 (0.7) |

| Breast cancer | 4 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 36 (5.4) |

| Lung cancer | 3 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 6 | 62 (9.3) |

| Bladder cancer | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 (0.4) |

| Renal cancer | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 11 (1.6) |

| Cervical cancer | 3 | 3 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 44 (6.6) |

| Periampullary cancer | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 13 (1.9) |

| Uterine sarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.3) |

| Vulval cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 (0.6) |

| Vaginal cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Ovarian cancer | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 14 (2.1) |

| Penile cancer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 (0.4) |

| Testicular cancer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.2) |

| GIST | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.4) |

| NHL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 (0.6) |

| Ureter cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Skin cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.1) |

| Peritoneal cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.4) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 (0.7) |

| Leukaemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Peripheral neural sheath cancer | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Bone cancer | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 (0.7) |

| Total | 77 | 96 | 103 | 131 | 111 | 108 | 41 | 667 (100) |

| Non-cancer | ||||||||

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 21 (63.6) |

| Parkinson disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (6.1) |

| COPD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 (9.1) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (3.0) |

| CKD | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 (12.1) |

| Depression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.1) |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 33 (100) |

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CKD: Chronic kidney disease, GIST: Gastrointestinal stromal tumour, NHL: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, JDWNRH: Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital

- (a) Percentage of cancer patients on home-based palliative care in Thimphu catered from the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH), Bhutan, between 2018 and 2024. (b) Percentage of non-cancer patients on home-based palliative care in Thimphu catered from the JDWNRH, Bhutan, between 2018 and 2024.

- Monthly total number of patients on home palliative care in Thimphu catered from the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital, Bhutan, between 2018 and 2024.

CHALLENGES AND SUPPORT

Embarking on the journey to launch the PC service meant starting from scratch. The home care team faced constraints of essential resources such as manpower, office space, transportation and a telecommunication system. After thorough exploration, an unused space inside the JDWNRH was designated as the office of the PC Unit for the 1st time in 2018. A month later, the office was required to shift to another space, which functioned till 2021. Since January 2022, the office has been relocated to the Kidu Medical Center (KMC), which has a spacious office shared with the Dialysis Unit. KMC is a royal gift to the people of Bhutan, which mainly caters to patients with cancer and kidney diseases.

The Royal Family’s unwavering dedication exemplifies unwavering support for the PC Unit and its patients. HRH Princess Kesang Wangmo Wangchuck supported the cause with her generous donations of two vehicles, which are used for transportation during home visits. In 2018, HRH also sponsored a study tour for the PC staff and some monks from the Central Monastic Body (CMB) to Thailand, which provided exposure, knowledge and further motivation. Moreover, HRH extended direct aid to poor patients, offering medical equipment and even protein supplements. In addition, Her Majesty the Queen Mother, Ashi Tshering Pem Wangchuck, made gracious monetary donations to help and support needy patients and families. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 lockdown, His Majesty the King’s Secretariat provided food supplies for poor patients.

The PC Service also collaborates with key stakeholders, including the BCS, CMB and TMD, to address the non-medical aspects of care. This community-centred approach aligns with the shift from institutional to home-based care. The BCS provides financial aid and conducts satisfaction surveys among patients. The CMB offers spiritual support, enhancing end-of-life care. The TMD provides various traditional therapies to the patients, particularly in the Oncology Ward.

International agencies such as Lien Collaborative and Asia Pacific Hospice and PC Network (APHN) based in Singapore; WHO SEARO, IPM, Calicut, India; St Christophers Hospice in London, United Kingdom; Two World’s Cancer Collaboration, Pain Relief and PC Society, Hyderabad, India and Health Volunteer Overseas, The United States of America provide guidance and support for training and service improvement.

Opioid analgesics such as codeine phosphate, morphine, pethidine, tramadol hydrochloride and fentanyl citrate are included in the essential medicines list of Bhutan.[15] The most commonly used opioid in palliative settings is morphine. The oral form of morphine (both sustained and immediate release) is available up to the district hospitals, whereas injectable form is available up to the referral hospitals. The challenges in using morphine include fear of prescribing and lack of knowledge about the benefits and safety of morphine amongst the prescribers. In an audit conducted at the national referral hospital of Bhutan, only 66.6% of cancer patients were prescribed morphine, 0.7% had regular morphine injections, and 23.8% did not receive any opioid prescriptions.[16] The national opioid requirements are estimated annually and procured once a year only from India. In Bhutan, there is no production of opioids. When there is a shortage of opioid supply due to the tedious process of procuring opioids, it is difficult to procure. As of now, oral morphine can be mobilised from nearby district hospitals to the community health centres using form III. However, many health workers are not aware of this procedure. To access opioids, patients travel to nearby district hospitals or stay with severe pain if they do not have the means to travel to the nearest district hospital. As per Chapter 12, section 90 of the Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances and Substance Abuse Act 2005, the Kingdom of Bhutan[17] quotes, ‘Manufacture, production, sale, export, import, storage, distribution, transportation, transhipment of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances for medical and scientific purposes in contravention of the terms or conditions of a license shall be liable to cancellation of the license and seizure of goods or a fine equivalent to a national daily wage for a maximum of 5 years or both’ unquote.

EDUCATION, TRAINING AND RESEARCH

Approaches to improve access to PC services include adequate national policies, programmes, resources and training on PC amongst health professionals.[18] The need for PC in Bhutan is huge and urgent, as assessed by Laabar et al. as a part of a PhD research project.[19,20] Educating the physicians, nurses, and other allied healthcare professionals on PC became crucial. Since the early 2000s, the WHO has recommended four foundational measures for establishing a sustainable PC and meaningful coverage – governmental policy, education, drug availability and implementation.[21] Laabar et al. have also developed a framework for PC in Bhutan based on recent WHO strategies, which also include involving the community and doing research.[22] The framework is contextualised to the sociocultural and spiritual realities of Bhutan.[23]

To improve the quality of PC services and extend it to the rest of the population in the country, many initiatives have been undertaken. A need for a PC physician was felt urgent. A general practitioner was immediately sent for a Fellowship in Palliative Medicine in Singapore. She (KB) graduated in early 2024, and she is now passionately leading the PC team in Bhutan.

Since 2023, several online PC trainings have been conducted for Bhutanese healthcare professionals. In July 2023, six weekly sessions, each 75 minutes in duration, were provided by Two Worlds Cancer Collaboration on Pediatric PC.[24] Forty participants, including paediatricians, residents, nurses and other healthcare professionals, participated. In early 2024, another similar online course on adult PC was conducted with support from Australasian Palliative Link International and Pallium India. More than 150 participants, including doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals from all levels of healthcare, attended the training. Now, the health workers across the country are aware of PC services. Recently, in early May 2024, a team of experts from APHN in Singapore resumed the face-to-face Training of Trainers (TOT) Workshop for Bhutanese healthcare professionals on PC Module 3, a continuation of the pre-COVID programme. The next TOT is planned to happen in October 2024. The participants are expected to implement the knowledge and skills and train other health workers in their respective districts. Bhutanese are very fortunate to receive support from APHN and Lien Collaborative for PC education.[25,26]

The Cancer Control Programme at the MoH has recently finalised the national PC guideline involving our technical experts, with the aim to take the services to all the districts utilising the existing manpower, drugs and equipment.

Hopes and expectations

There is an increasing need for PC services globally with changing illness trajectories, ageing population trends and advances in healthcare technologies. Patients with actual or potentially life-threatening and their families need comprehensive care aiming to maintain and improve their quality of life.[27] Despite the extremely limited resources, PC in Bhutan has been developing steadily since its inception. Results so far have also highlighted the potential for nurses to play an effective role in PC. While the progress so far is commendable, there is a pressing need for further action. In a study by Laabar et al., the health-care professionals in Bhutan have highlighted the need for suitable policy, education and making essential PC medicines available at all levels of health care.[28] It is important to develop a national strategy and action plan in considering the already acquired rich experiences. Experience has shown that the possible way forwards will be through policy guidelines, awareness building across various sections of the society and further international collaboration. In addition, increasing access and affordability of essential medicines, regional education and training to complement the national needs for human resources to improve staffing and skill levels are essential. With improved human resources, education and services, we envision establishing a dedicated department of Palliative Medicine at the JDWNRH, which would support catering PC services at all levels of health care across the country.

CONCLUSION

Although PC service is in the infancy stage at the moment, the future appears promising with the current level of determination and passion amongst health workers, commitment from the MoH and Royal support. We aim to have our people trained to use the locally available resources for long-term sustainability.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to personal information protection, patient privacy regulation, medical, institutional data regulatory policies, etc., but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of the administration of JDWNRH, Thimphu, Bhutan.

Authors’ contributions

Namkha Dorji/Tara Devi Laabar/Kinley Bhut/Sangay Tshering: Study conception and design, Namkha Dorji/Yangden Yangden/Yeshey Dorjey: Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Namkha Dorji/Tara Devi Laabar/Yangden Yangden: Drafting of manuscript, Namkha Dorji/Tara Devi Laabar/Kinley Bhuti/Giam Cheong Leong/Sangay Tshering: Critical revision, Namkha Dorji/Tara Devi Laabar/Kinley Bhut/Yangden Yangden/Sangay Tshering/Yeshey Dorjey/Giam Cheong Leong: Giving final approval for the final version to be published.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Palliative Care Definition. Available from: https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/projects/consensus-based-definition-of-palliative-care/definition [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Alleviating the Access Abyss in Palliative Care and Pain Relief-an Imperative of Universal Health Coverage: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet Comm. 2018;391:1391-454.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health-care-conference/palliative.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- 2023 Vital Statistics Report 2023. Available from: https://www.nsb.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2024/04/vsr-2023-for-print.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Bhutan [Country Overview] 2024. Available from: https://data.who.int/countries/064 [Last accessed on 2024 May 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan. 2008. Parliament of Bhutan. (1st ed). Available from: https://www.dlgdm.gov.bt/storage/upload-documents/2021/9/20/constitution-of-bhutan-2008.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Jun 07]

- [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare and Happiness in the Kingdom of Bhutan. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:107-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progress and Delivery of Health Care in Bhutan, the Land of the Thunder Dragon and Gross National Happiness. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:731-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarming Prevalence and Clustering of Modifiable Noncommunicable Disease Risk Factors among Adults in Bhutan: A Nationwide Cross-sectional Community Survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:975.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutan Cancer Control Strategy 2019-2025. 2019. Ministry of Health. Available from: https://www.iccp-portal.org/plans/bhutan-cancer-control-strategy-2019%e2%80%932025 [Last accessed on 2024 Jun 07]

- [Google Scholar]

- Bhutan Tutors Take Home the Message of Palliative Care. 2016. The Hindu. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/thiruvananthapuram/bhutan-tutors-take-home-the-message-of-palliative-care/article14431772.ece [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care the Emerging Field in Bhutan. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23:108-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launch of Palliative Care by Her Royal Highness Ashi Kesang Wangmo Wangchuck. 2020. Ministry of Health. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.bt/launch-of-palliative-care-by-her-royal-highness-ashikesang-wangmo-wangchuck [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Virtual consultations: The Experience of Oncology and Palliative Care Healthcare Professionals. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23:114.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essential Medicine and Technology Division. 2016. Ministry of Health, Bhutan. :1-213. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/moh-files/2016/08/national-essential-medicines-formulary-2016.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Sep 12]

- [Google Scholar]

- Audit at the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital's Palliative Care Unit, Covering the Period from August 01, 2022 to August 01, 2023. Bhutan Health J. 2023;9:2022-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Psychotropic Substances and Substance Abuse Act 2005. 2005. Kingdom of Bhutan. Available from: https://oag.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/narcotic-drugspsychotropic-substance-substance-abuse-act-of-bhutande.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care Needs among Patients with Advanced Illnesses in Bhutan. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20:8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Support Needs for Bhutanese Family Members Taking Care of Loved Ones Diagnosed with Advanced Illness. J Palliat Care. 2022;37:401-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care: The Public Health Strategy. J Public Health Policy. 2007;28:42-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240033351 [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a Palliative Care Model - Socially. 2022. Culturally and Spiritually Applicable for the Kingdom of Bhutan. Available from: https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/development-of-a-palliative-care-model-socially-culturally-and-sp/fingerprints [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Paediatric Palliative Care ECHO Programme in Bhutan: A New Era. 2023. Available from: https://ehospice.com/inter_childrens_posts/paediatric-palliative-care-echo-programme-in-bhutan-a-new-era [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network. Available from: https://aphn.org [Last accessed on 2024 May 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- LIEN Collaborative for Palliative Care. Available from: https://www.liencollab.org [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care: A Concept Analysis Review. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022;8:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Professionals' Views on How Palliative Care should be Delivered in Bhutan: A Qualitative Study. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2:e0000775.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]