Translate this page into:

Parent's Perspectives on the End-of-life Care of their Child with Cancer: Indian Perspective

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sneha Magatha Latha; E-mail: drmslatha@yahoo.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Parents report that end-of-life decisions are the most difficult treatment-related decisions that they face during their child cancer experience. Research from the parent's perspective of the quality of end-of-life care of their cancer children is scarce, particularly in developing countries like India.

Aims:

This study aimed to identify the symptoms (medical/social/emotional) that most concerned parents at the end-of-life care of their cancer child and to identify the strategies parents found to be helpful during this period.

Settings and Design:

We wanted to conduct this to focus on the parents perspectives on their cancer child's end-of-life care and to address the issues that could contribute to the comfort of the families witnessing their child's suffering.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted at Sri Ramachandra University, Chennai, a Tertiary Care Pediatric Hemato Oncology Unit. Parents who lost their child to cancer, treated in our institution were interviewed with a validated prepared questionnaire. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software package.

Results:

Toward death, dullness (30%), irritability (30%), and withdrawn from surroundings (10%) were the most common symptoms encountered. About 30% of the children had fear to be alone. About 50% of the children had the fear of death. Pain, fatigue, loss of appetite were the main distressful symptoms that these children suffered from parents’ perspective. Though the parents accepted that the child was treated for these symptoms, the symptom relief was seldom successful.

Conclusion:

The conclusion of the study was that at the end of their child's life, parents value obtaining adequate information and communication, being physically present with the child, preferred adequate pain management, social support, and empathic relationships by the health staff members.

Keywords

End-of-life care

Parents perspectives

Pediatric malignancies

INTRODUCTION

The quality of life is a common phrase, and all the human endeavors are aimed at improving the quality of life, but issues pertaining to quality of death are less commonly discussed. Although pediatric malignancies cure rate has improved considerably, nearly 20% of pediatric patients with cancer still die from their disease.[1] Parents report that end-of-life decisions are the most difficult treatment-related decisions that they face during their child's cancer experience. While parents play a major role in the practical and emotional aspects of child care, research into the parents’ perspective of the quality of end-of-life care is scarce.

The commonly reported symptoms such as pain, fatigue, anorexia, and dyspnea are suffered by over 75% of patients and psychological problems such as uncontrolled anxiety, sadness, and depression are often not recognized and hence not treated effectively. The child's suffering from these symptoms is one of the major concerns of the parents, diminishing their quality of life and adding to the emotional burden of the families. Retrospective studies have always reported that majority of these symptoms were untreated or unsuccessfully treated.

Hence, we undertook a study on parents’ perspectives about their cancer child's end-of-life care.

Subjects and methods

To date, research has been limited and has not focused much on the preferences of the parents and children with advanced cancer in developing countries like India. Knowledge of patients’ preferences about their end-of-life care of their children would enable clinicians to accolade those preferences where possible. This could provide comfort to parents after the loss of their child and reassure clinicians about the quality of the care they provide.

Hence, we wanted to conduct this study to focus on the parents perspectives on their cancer child's end-of-life care – symptom management, quality of child's life, end-of-life decisions, and social support by the health care team to recommend actual and reasonable support systems for the similar families.

Aims and objectives

This study aimed at

-

To identify and describe the symptoms (medical/social/emotional) that most concerned parents during the last days of their child's life

-

To identify strategies, parents identified as helpful during this period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at Sri Ramachandra Medical Centre, Chennai, a Tertiary Care Center with a Paediatric Heamto Oncology Unit treating approximately hundred newly diagnosed patients per year.

Inclusion criteria

Parents who lost their child aged between 0 and 18 years of cancer treated in our institution and whose child had died at least 3 months before the study period were considered eligible.

Exclusion criteria

A child who underwent cancer treatment at a different center and parents who lost the child at <3 months before the study period to give them adequate time to overcome the grief.

Initially, we contacted the parents over the phone and got their consent for the study. The parents who gave their consent were then called to the institution and were interviewed by a trained clinical psychologist with one of the pediatric oncology team members and asked to fill up a questionnaire with the discussion.

The questionnaire was developed on the basis of a review of the literature published and the opinions from few parents who have lost their child due to cancer and also from personal experiences of pediatric oncologists from our institution and validated with their colleagues from national and international pediatric oncology units. Whenever possible, the questions were drawn from previously validated surveys. The variables used in the questionnaire are given in Annexure 1. The variables were graded with five-point Likert scales. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software package (Dell Statistica, Tulsa, Oklahoma 74104. USA). The study was cleared by the Ethics Committee of our University and funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research.

RESULTS

Parents and child characteristics

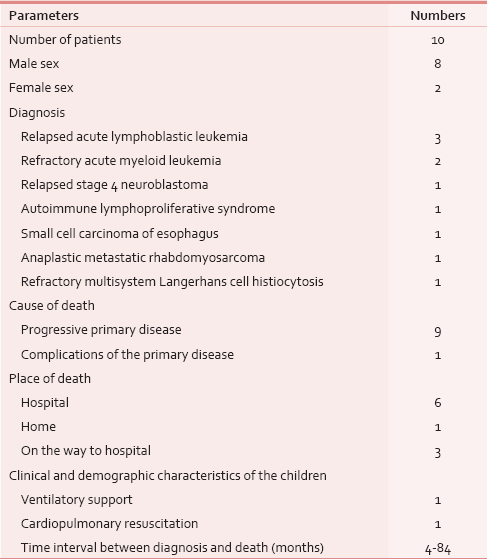

Seven parents had completed higher school education, while two of them had completed postgraduation, and one had completed undergraduation. Eight of the parents were unskilled laborers while two were working in IT company. None of the mothers were working. Five of the families were from urban areas and five from rural areas. Eight of them were followers of Hinduism, and two belonged to Muslim community. The children's demographic and clinical profile are given in Table 1.

Symptoms and suffering

Among the psychological symptoms noted at the end-of-life care, dullness (30%), irritability (30%), and withdrawn (10%) were found to be most common. Seven of the children were interested in playing even during their terminal illness, but four of them were not willing to talk to the parents about their feelings. Three of the children were afraid to be alone according to parents. Five of the children had the fear of death. Pain, fatigue, and loss of appetite were the main distressful symptoms that these children suffered from as per parents perspectives. Though the parents accepted that the child was treated for these symptoms, they were seldom successful, with relief reported only in <30% [Figure 1].

- Proportion of children treated for various symptoms and the success rates of treatment

Quality of care rendered by the physicians

The parents accepted that the 70% of the times, the physicians were always available for their queries and 50% of them considered their communication as excellent, and 30% considered it as good.

About 60% of them rated the standard of care as excellent, while another 60% rated social support rendered as excellent, and 40% rated emotional support as excellent, and 70% of them wanted the physician to contact them after the loss of the child and 60% of them wanted the treating physicians to attend the funeral.

End-of-life care decisions by parents

About 50% of them were able to understand the concept of palliation versus curative option while 20% could not understand at all. About 80% of them were able to come in terms with palliative mode of treatment, while 20% could not. Only 40% of them opted for alternative medicine and 70% of them accepted that it worsened the symptoms. Only 25% of them reported a temporary relief. About 80% of the parents accepted that physicians and nursing staff were actively involved in the care of the child, and there was no change in their attitude toward the end-of-life care after the child was told to have an incurable disease. About 60% of them wanted their child to be at the hospital during the period of death, and 40% opted home to be the place of death. Among the other issues that added to their miseries during the terminal illness of the child, financial issues contributed 40% and intravenous access issues and other invasive investigations – 40%, and hospital administrative issues −20%. About 70% of the parents felt guilty for their child's worsening condition, and 80% felt that the physicians were concerned about their guilty feeling of not able to save their child. When questioned about what made them to opt for aggressive therapy toward the end-of-life, 60% reported that they hoped for a miracle, while 30% wanted to do everything possible to reduce the suffering. Retrospectively, 70% of them felt that what they did was right as they wanted to help the child in all possible ways.

DISCUSSION

Optimizing the quality of the medical care given at the end-of-life in cancer children is being recognized as an important health care objective. Relief of the child's end-of-life distress will have a long-lasting implication for the bereaved parents, who are negatively affected by their child's experience of unmanageable symptoms, years beyond the death.

To achieve an acceptable quality of life in the setting of pain, fatigue, and dyspnea is a very difficult task. In a study by von Lützau et al. in Germany, who interviewed 48 parents of cancer children, it was found that pain and fatigue were the most distressing symptoms and families have reported 65% symptomatic relief which is in contrast to an Australian study by Heath et al. where families reported that treatment for specific symptoms was successful in only 47% of those with pain, 18% of those with fatigue, and 17% of those with poor appetite.[23]

Hence, nonpharmacologic approaches that can augment medical therapies should be tried. Studies have proved the efficacy of combined pharmacologic therapies and psychological interventions in decreasing both the child and parent distress. Some of the interventions tried were massage, physical therapy, behavior, and cognitive techniques such as play therapy, music therapy, distraction, or guided imagery.[4]

It is understandable that parents have continued hope for life extension even until the very end-of-life in children with advanced cancer as shown by Bluebond-Langner et al.[5] Hechler et al. too reviewed 48 parents and found that 50% of the children obtained cancer-directed therapy at the end-of-life, which explains the difficult situation of the parents in understanding the concept of palliation versus curative options when they see their child suffer.[6] When the prognosis is bad, the parents were willing to let their child undergo major adverse effects for the very small objective benefit of avoiding death. But, retrospectively, majority of them revealed that they would not recommend it to other families, and if they had realized in advance that the treatment would cause their dying child to suffer more, they would not have opted for it.[7] The common reasons cited by the parents for opting aggressive therapies toward the end-of-life was to relieve the suffering and extend the life, but retrospectively they agreed that they were ineffective even for symptom management. This necessitates the evaluation of the appropriateness of administering chemotherapy to pediatric patients with cancer when they are close to death.

Worldwide, children still continue to die in substantial numbers in the acute care setting rather than at home or hospice as preferred by the families. The percentages of hospital death for pediatric patients with cancer were 23-48% in England, 41-56% in the United States, 52-60% in Germany, 60% in the Netherlands, 61% in Sweden, and 71% in Japan. But Heath et al. reports a realistic approach of the end-of-life care for Australian children dying of cancer, as 89% of the families preferred the child to die at home and 61% died at home and of those who died in hospital, less than a quarter died in intensive care unit.[3]

Tzuh Tang et al. reviewed the end-of-life care of Taiwanese children who died of cancer from 2001 to 2006 and found that 52.5% of them received chemotherapy in their last month of life, 57% received intensive care, 48.2% had mechanical ventilation, 69.5% had longer than 14 days of stay in hospital, and 78.8% died in acute care hospital, emphasizing the fact that end-of-life care is still being managed aggressively in most of the countries.[8] Whereas, in the United States and Germany, 35-44% and 41%, respectively, of pediatric patients with cancer were enrolled in hospice care.[9] Relatively, high rates of death at home or hospice care and low rates of unsuccessful medical interventions are indicators of effective end-of-life care measures.

Heath et al. have proved that if it is feasible to provide out of hospital palliative care services, most of the families were willing to opt for it.[3] This highlights the need to start more local and regional hospice centers. The major barrier to adequate palliative care is the fragmentation of the services, as they are not available at one place. The leading obstacle to providing hospice care to children was an association of the hospice concept with death rather than life enhancement, lack of clarity when to refer and physician's reluctance in making the referral.

Surveys of bereaved parents of children with cancer have revealed that when parents recognize the poor prognosis of the child much earlier, they have had earlier discussions about hospice care, had earlier institution of do not resuscitate orders, and decreased use of cancer-directed therapy at the end-of-life.[10] Honest communication about prognosis had been found to be associated with greater parental peace of mind and trust in the physician.[11]

Caring for their dying children creates a sense of failure and feeling of powerlessness against their child's illness in the parent's mindset, and most of them experience a profound feeling of guilt. But when they are able to satisfy themselves that they had been a good parent to their seriously ill child, it helps them to emotionally survive the death of their child.[12] Hence, it is essential that the physicians concentrate to relieve the guilty feeling of the parents.

Physicians often feel that talking about the death of their child will make the parents relive the grief, whereas it has been reported by Macdonald et al. that the grieving parents want their grief to be acknowledged and want the physicians to contact them after the loss.[13] Failing to acknowledge the death of the child can add to the family's pain and hence a phone call or a visit to the family should be encouraged.[14] The most helpful response after a child's death is to provide an opportunity to meet with the parents, face to face and to just listen, responding in ways that encourage the parents to talk.

Limitations of the study

Our study is only a pilot study with ten patients as small sample size, a single institutional study, and based primarily on parents perspectives which might not have reflected the actual experience of the child.

CONCLUSION

In developing countries, with scarce financial resources and the increasing magnitude of competing problems, little resources are left for hospice and palliative care services. However, the human factor should not be underestimated, as end-of-life of care is far more than medical treatments and pain killers. Greater attention should be paid to symptom control and psychological aspects of the caregivers.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- The epidemiology of cancer in children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. :1-16.

- Children dying from cancer: Parents’ perspectives on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death, and end-of-life decisions. J Palliat Care. 2012;28:274-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer: An Australian perspective. Med J Aust. 2010;192:71-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care for infants, children, adolescents, and their families. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:163-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding parents’ approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2414-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parents’ perspective on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death and end-of-life decisions for children dying from cancer. Klin Padiatr. 2008;220:166-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5979-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric end-of-life care for Taiwanese children who died as a result of cancer from 2001 through 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:890-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Race does not influence do-not-resuscitate status or the number or timing of end-of-life care discussions at a pediatric oncology referral center. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:71-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: Impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284:2469-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decision making by parents of children with incurable cancer who opt for enrollment on a phase I trial compared with choosing a do not resuscitate/terminal care option. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3292-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parental perspectives on hospital staff members’ acts of kindness and commemoration after a child's death. Pediatrics. 2005;116:884-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Supporting the family after the death of a child. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1164-9.

- [Google Scholar]

ANNEXURE 1

Questionnaire

Parents perspectives on the end-of-life care of their child: Rating of the quality of care

Patient details:

Name of the child (optional): Hospital No: Gender Age: Diagnosis Duration between diagnosis and the loss of the child (months) Cause of death

Disease progression Complications of the primary disease Treatment complications Infections Place of death:

Hospital Home Hospice On the way to hospital If the child died in hospital:

Whether the patient was intubated in the last 24h? Whether cardiopulmonary resuscitation was done? Whether ventilator or any other type of support was withdrawn? Not know Not applicable

Parents details:

Father:

Age Educational qualification:

Undergraduate Postgraduate Professional course School Occupation:

Skilled Unskilled Professional Annual income:

No income <100,000 100,000-200,000 >200,000 Mother:

Age: Educational qualification:

Undergraduate Postgraduate Professional course School Occupation:

Skilled Unskilled Professional Homemaker Annual income:

No income <100,000 100,000-300,000 >300,000 Native place:

Urban Rural Religion

Hindu Christian Muslim Other

Questionnaire:

Psychological symptoms:

Changes In Behavior:

Irritability Dull Withdrawn Interested in any playful/leisure activities

Yes No Unwilling to talk to the parents about their feelings

Yes No Fear of death

Yes No Fear of being alone

Yes No Did the child receive treatment for the symptoms?

Fatigue: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Pain: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Loss of appetite: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Dyspnea: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Anxiety: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Constipation: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Insomnia: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Vomiting: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Diarrhea: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Bleeding: Yes/No If yes, how successful was the treatment?

Not useful Some impact Useful Were the physicians easily approachable to all your queries about your child during the terminal days?

Hardly ever Occasionally Sometimes Frequently Almost always How would you rate the communication about your child's progressive disease condition by the treating physician?

Very poor Poor Average Good Excellent Were you able to understand the concept of palliative care versus curative care?

Not at all Quite a bit Completely How well did doctor's counseling help you come in terms with acceptance of the end-of-life care?

Totally unacceptable Unacceptable Slightly acceptable Acceptable Perfectly acceptable Was the physician actively involved in the care at the end-of-life?

Yes No Did your physician discuss about the alternative/native/complementary medicine?

Yes No Did you opt for alternative medicine?

Yes No If yes, details

Siddha Ayurvedic Homeopathy Acupuncture Others Did you feel that the alternative medicine improved/worsened his symptoms or suffering?

Much more worsening Somewhat worse About the same Somewhat better Much better What were the issues that added to your misery while caring for your child during his/her terminal days?

Hospital administrative issues Invasive procedures Financial IV issues Other Where did you want your child to be during the terminal illness?

Hospital Home Relatives house others Have you ever felt guilty on your part for his/her deteriorated condition?

Yes No If yes reason…

N/A For having stopped the curative intension chemotherapy when the disease became uncontrolled and progressive/for opting palliative intend chemotherapy when the disease relapsed Did you feel that the doctors were insensitive at your helplessness and guilt of not being able to save your child?

Yes No Did the treating physicians devote adequate time with you/your child after the declaration of palliative care for your child?

Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always 16. Did you feel treatment in a different method in the same hospital or another hospital would have helped/impacted the outcome?

Yes No If yes, how?…

N/A Once your child had been declared to be on palliative care, did you find any difference in the attitude of the nursing staff or treating physicians toward your child?

Yes No If yes... details:

N/A Retrospectively what do you think you could have done to better his/her terminal days in any dimension? When the physician wanted to discuss about the end-of-life decisions;

You never wanted to discuss about it You wanted to postpone the discussion Though it was uncomfortable, you were willing for discussing it How would you rate the following regarding your child's treatment:

Standard of care:

Poor Fair Good Very good Excellent Emotional care:

Poor Fair Good Very good Excellent Communication:

Poor Fair Good Very good Excellent Social support:

Poor Fair Good Very good Excellent What made you to opt for continuing aggressive therapy in spite of the physician's declaration that continuing chemotherapy will not alter the course of the disease anymore?

You felt that chemotherapy will reduce his suffering You did not want to give up on your child You were hoping for a miracle You wanted to do everything possible for your child N/A Retrospectively what do you feel about your decisions?

You should have opted only for supportive therapy as it would have lessened his/her suffering instead of aggressive curative treatment What you opted was right, as you wanted to try every possible option for your child N/A Would you have preferred to meet the medical team after your child's death or you would have preferred the physician to contact you after your child's death in telephone?

Yes No Did you think the medical team (doctor/nurse) should have attended the funeral?

Yes No