Translate this page into:

Perspective of patients, patients’ families, and healthcare providers towards designing and delivering hospice care services in a middle income Country

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

In view of the recent surge in chronic disease rates and elderly population in the developing countries, there is an urgent felt need for palliative and hospice care services. The present study investigates the views and attitudes of patients and their families, physicians, nurses, healthcare administrators, and insurers regarding designing and delivering hospice care service in a middle income country.

Materials and Methods:

In this qualitative study, the required data was collected using semi structured interviews and was analyzed using thematic analysis. Totally 65 participants from hospitals and Tabriz University of Medical Sciences were selected purposively to achieve data saturation.

Results:

Analyzing the data, five main themes (barriers, facilitators, strategies, attitudes, and service provider) were extracted. Barriers included financial issues, cultural-religious beliefs, patient and family-related obstacles, and barriers related to healthcare system. Facilitators included family-related issues, cultural-religious beliefs, as well as facilitators associated with patients, healthcare status, and benefits of hospice service. Most participants (79%) had positive attitude towards hospice care service. Participant suggested 10 ways to design and deliver effective and efficient hospice care service. They thought the presence of physicians, nurses, and psychologists and other specialists and clergy were necessary in the hospice care team.

Conclusion:

Due to lack of experience in hospice care in developing countries, research for identifying probable barriers and appropriate management for reducing unsuccessfulness in designing and delivering hospice care service seems necessary. Input from the facilitators and their suggested solutions can be useful in planning the policy for hospice care system.

Keywords

Attitudes

Developing countries

Healthcare administrator

Hospice care

Insurance official

Iran

Patients

Patients’ families

Physicians

Nurses

INTRODUCTION

Chronic disease is considered as one of the major problems and issues of health and social care system in current societies.[1] Patients in the last stage of life are patients who are not expected to live more than 6 months based on current medical knowledge.[2] Nowadays, paying attention to these patients and their families has gained increasing importance.[3] These patients have different physical, social, and psychological needs, and most of these deaths (approximately 70%) occur in hospitals.[4] In hospitals with advanced diagnostic and treatment technologies, patients are told that there is nothing more to be done for them. Often such patients are deprived of the benefits of professional care, thus impacting their quality of life and death.[56] At present, the main approach to care for these patients in developed countries is hospice care service. The need for improved hospice care in developing countries is great. Generally, hospice means specialized care that provides comfort and support to the patients and their families when long-term treatment has not worked and death is inevitable. This care neither increases the life duration nor decreases it, but they improve the quality of life of end-of-life patients. The goal of hospice care is to support the highest possible quality of life for whatever time remains. Hospice focuses on caring and not curing.[7]

Hospice care programs cared for more than 885,000 people in the United States in 2002. And it has increased by 15% in recent years. Cancer remains the most common (approximately 90%) primary diagnosis for patients in hospice care.[8] The number of elderly is increasing in the developed world and accelerating in the developing world; awareness of how we care for this population is gaining increased attention. Agnes et al.,[7] have shown that there is significant difference between the beliefs and attitudes of American doctors and Hungarian ones about end-of-life care. According to successful experience of some developed countries, there is an urgent need for designing and delivering hospice care in developing countries. Therefore, the present study is going to investigate beliefs and attitudes of stakeholders of this service (such as patients and their families, physicians, nurses, hospital administrators, health service managers, and insurance authorities) toward planning and delivering hospice care for end-of-life patients in developing countries (case study of Iran) via qualitative methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

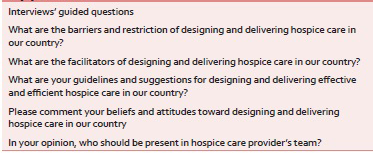

This study used qualitative method of research. The strength of qualitative research is its ability to provide complex textual descriptions of how people experience a given research issue.[9] The participants of the study were employers in Tabriz University of Medical Sciences hospital and faculties, patients who were referred to these hospitals of Tabriz, and insurance experts of Azerbaijan-e-Sharqi province, Iran. These people were selected because they had a lot of experience communicating with end-of-life patients and also had broad knowledge and information about hospice care. Inclusion criteria for this study included having at least 5 years working experience with end-of-life patients, having adequate and appropriate knowledge and information about hospice and palliative care, and their willingness and ability to participate in this study. Purposive sampling, one of the most common sampling strategies, was used for selecting heterogeneous groups (patients, patients’ families, service providers, public health officials, and insurance executives). Individuals who had the largest and richest information and were able to make their data available to the researchers were selected as participants of the study.[10] This process continued until data saturation. The point of closure was reached when the acquired information became repetitive and contained no new ideas, in a way that the researcher was reasonably assured that the inclusion of additional participants was unlikely to result in any new ideas.[3] There were 65 participants. Data was collected through semi structured interview. During interview, guided questions were used in the local language –Turkish [Appendix 1]. Duration of each interview varied between 45 and 90 min. The participants’ statement was recorded with their consent during the interview by voice recorder set and it was also written by interviewers. After completion of the interview, the researchers listened to each interview several times, and these were transcribed verbatim in Microsoft Office Word software (version 2007). For analyzing the required data, thematic analysis was used. Response Validity was used for establishing rigor of the required data. For study rigor at the end of session, the subjects were summed, and were asked to endorse them (respondent validity). Also, peer check and immersion strategies (methods of creating rigor) were used.[11] To consider ethical issues which are important in qualitative studies,[1213] the researchers obtained informed consent from participants of the study. The participants were allowed to leave the study at any time they wanted. In addition, the objectives of the study were explained to the participants by researchers. The approval of regional committee for research ethics which was located in Tabriz University of Medical Sciences was obtained.

RESULTS

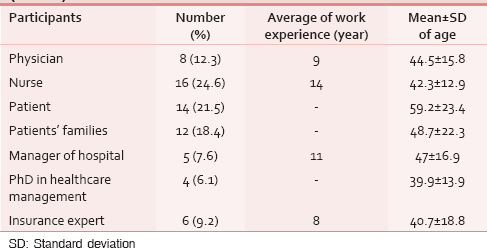

Demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

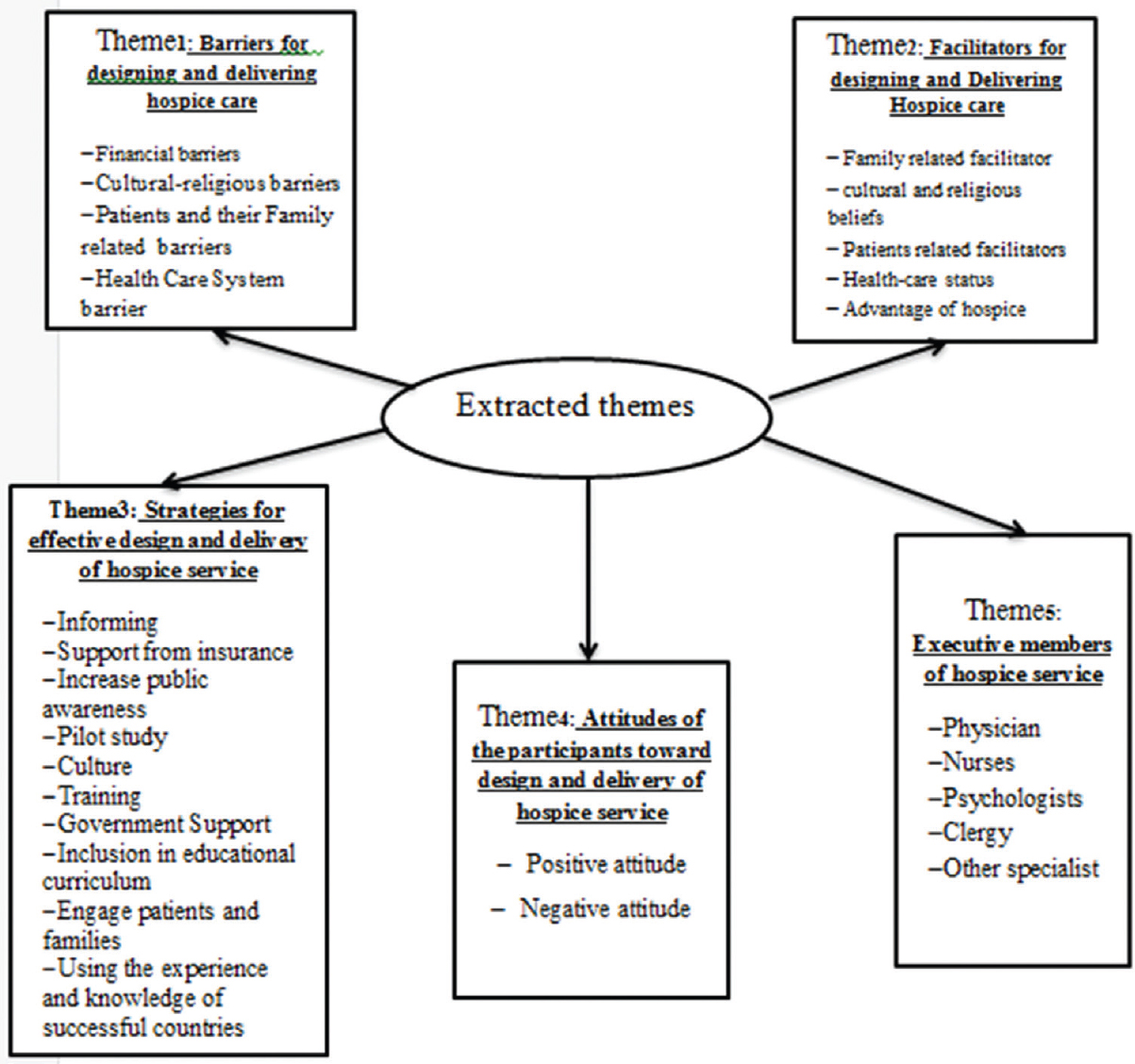

In this study, after analyzing and encoding of the participants’ statements, five major themes including barriers for designing and delivering hospice care, factors facilitating hospice care, strategies for effective design and delivery of hospice service, participants’ attitude toward designing and delivering hospice service, and executive members of this service were extracted [Figure 1].

- Five extracted themes from participants prospective towards design and delivery of hospice service in Iran

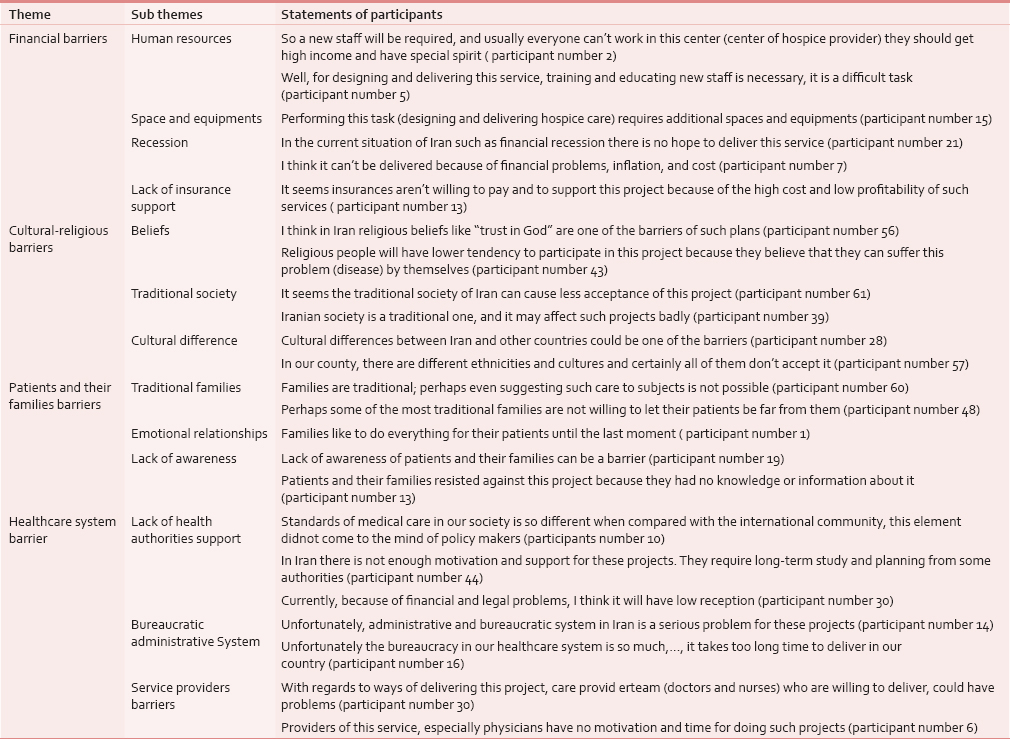

Barriers for designing and delivering of hospice care service from the perspective of participants were extracted from four major themes and 14 subthemes, which are shown in Table 2.

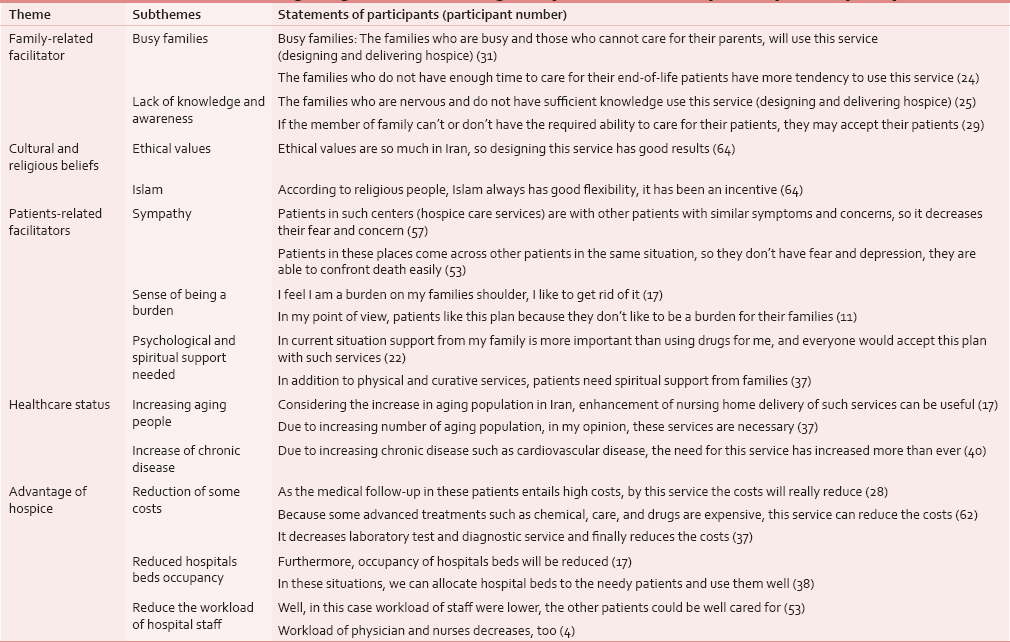

Facilitators of designing and delivering hospice care from participant perspective were extracted from five major themes and 12 subthemes, which are shown in Table 3.

By analyzing the views and attitudes of the participants, two major themes of “positive attitude” and “negative attitude” were extracted. We point them briefly:

Positive attitude

In this study, 49 participants (79%) had positive attitude towards designing and delivering of hospice care. In this regard, participant 4 stated that: “I meet cancer patients a lot in our unit, there is no hope in their lives … now that you speak about this issue (design and deliver hospice care), I think it's a great idea and it is useful in our country“. Or participant 18 in this regard had such an idea: “Generally the hospice care plan is essential and could be effective and good, if performed with comprehensive and good planning, especially considering the prevalence of chronic disease and aging population.

Negative attitude

Despite the positive attitude of the majority of the participants, some of them did not have positive view or perspective towards hospice care. For example, participant number 32 believed that “…in my point of view, designing and delivering of this plan will be time consuming and difficult, it's hard to launch such services…“. Number of participants stated that resistance of some executive authorities is the reason of their negative view. Number 16 participant believed that “this plan like other projects in Iran will meet with failure, due to much resistance and opposition of some people“.

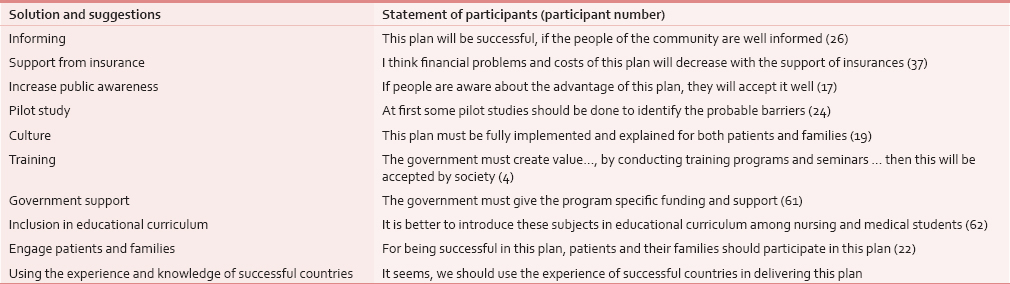

In this study, participants were asked to present their solution and suggestion for effective and efficient planning and delivering hospice care and eliminating probable barriers. By analyzing and coding the participants’ suggestion and recommendation, finally 10 outcomes could be extracted which are shown in Table 4 with statement of participants.

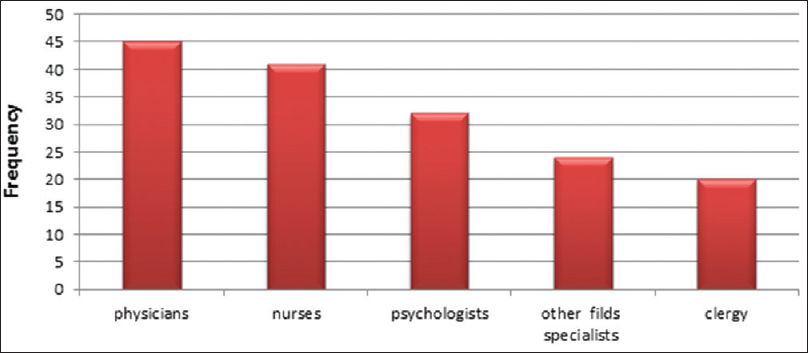

At the end of the interview, participants were asked to name the people who should be present in the hospice service team. Among 65 participants, 51 of them responded to this question. Figure 2 shows the frequency of individuals.

- People who should be present in provider hospice service team from participant's perspective (N = 51)

Participants stated that attending physician, nurses, psychologists, clergy, and other specialist are necessary in provider team [other field specialists - Figure 2].

DISCUSSION

The results of this study reveal that four major barriers in the planning and delivering of hospice service includes financial barriers, cultural-religious barrier, patients and their family-related issues, and barriers related to health care system. From participants’ perspective facilitators for designing and delivering hospice care system included facilitators related to families, cultural-religious beliefs, facilitators related to patients, healthcare status, and benefits of hospice service. Most of the participants in this study had a positive view and belief toward this service. From participants’ perspective, 10 different outcomes were presented for designing and delivering efficient and effective hospice care. Participants stated that the inclusion of physicians, nurses, psychologists, clergy, and other specialists is necessary in provider team. The participants of this study pointed that financial barriers such as human resources, space and new equipment, lack of insurance support, economic recession, and high costs were the main barriers of delivering hospice care. In the qualitative study of Brueckner et al.,[14] in Germany, they believed that financial issues and problems is one of the barriers for managing hospice care, too. Therefore, conducting a pilot study to determine the cost-effectiveness of the service and financial evaluation studies, as well as appropriate steps to control and reduce the cost of hospice care is essential before planning and delivering this service.

The other main barriers mentioned in this study, was cultural and religious beliefs of people. These barriers were disclosed in the study of Finestone and Inderwies.[15] One of the barriers from the participants’ perspective was cultural differences in these countries. It was noted that the cultures of these countries were different when compared with western countries. As in these countries, there are immigrants who are regarded as minorities. In another study by Kapo and Macmoran, in USA hospice service was less accessed by Native Americans.[16] Other related studies showed that cultural differences had a huge impact on the acceptance and use of hospice service.[1718] Therefore, according to the results of these studies and previous related studies, it can be concluded that for planning and delivering hospice care in each country, cultural difference within that country should be considered. Hence, survey of perspectives of population and minorities of the community and applying their comments or suggestions in planning hospice care and designing comprehensive and flexible hospice care can be helpful. It is imperative that authorities and administrators consider this point.

Other major barriers in terms of participants which can affect planning and delivering hospice care are related to the healthcare system. One of the barriers is lack of motivation and support of service providers, especially physicians. The result of other studies showed that in spite of positive views and attitudes of physicians’ and other healthcare system providers; they don't have great motivation and desire to participate in this service.[19202122] Thus, considering the crucial and effective role of providers, for planning and delivering hospice care in each country at first cooperation and assistance of service providers, especially physicians and nurses is required, and to do so financial and nonfinancial incentives for participating in this study should be remarkable. In countries like Iran, where hospice care is not designed and delivered yet, training and education of physicians, nurses, and other people who can be effective in this area by involving them in providing the service can be very helpful.

For participants, probable advantages of hospice care over hospital services include its facilitators of designing and delivering. It was noticed in related studies conducted in other countries trying to compare hospice care and provided services to end-of-life patients, that quality of hospice services were higher and satisfaction rate of hospice service was more than that of hospital services among families.[232425] Even Connor's study showed that the patients who were cared in hospice centers had survived approximately 29 days more than other similar patients.[26] Other advantages of hospice service from participants perspectives was reducing costs, this subject was mentioned in other related studies.[272829] It is necessary to point that wherever hospice care was delivered, its benefits were obvious and hospice was compatible with other services in those cases. But the advantages in this study were asserted from participants’ point of view and could not be said with certainly that it will happen in developing countries and Iran, if it delivered.

According to the results of this study it can be deduced that the patient's family can have a key role in providing hospice care. In this context, Hauser and Kramer[30] believed that families had direct and primary role in delivering hospice care service for patients. Deny et al.,[31] have pointed the role of family members, especially caring skills. Hence, for designing and launching hospice service, it is better, that the necessary training should be given to patients’ family members, and their support and assistance must be used appropriately.

In this study, the majority of participants (79%) had positive attitude toward hospice care service. Previous studies indicated that majority of participants had positive attitude and view toward hospice service.[710323334] Therefore, positive attitudes and views can be regarded as an opportunity for designing and delivering hospice care and it should be used best.

One of the best strategies suggested by participants of this study, was involving patients and their families in planning and delivering hospice service. This issue was addressed in Bradley et al., as well.[35] One of the other strategies which were mentioned in this study was including training material in educational curriculum particularly in the field of nursing and medicine. These cases have been referred in previous studies.[3637] Therefore, revising physicians and nurses’ educational program to include end-of-life care courses can be effective. Also seminars, congress, and training courses can be useful in this regard. The results of previous studies showed the perception of importance and role of it and efforts for educational or communication and cauterizing.[38394041] This subject is important and sensitive and needs further attention because the participants believed that people in developing countries and Iran have a rich culture, but on the other hand they are traditional and adhere to some traditional beliefs.

Participants of this study believe that presence of physicians, nurses, psychologists, and other specialists in other disciplines and clergy is essential in service provider team. Presence of physician among service provider team members was the major necessity. In previous studies, the presence of at least one physician in hospice providers’ team was necessary.[4243] In this study nobody mentioned the necessity of social workers’ presence in the hospice providers’ team, but researchers suggest that the presence of social workers were essential. In other previous studies, researches have also pointed out the importance of the people offering these services.[4445] Two major points should be taken into consideration while assigning the hospice care providers in any country. First, the hospice provider team must be various, according to the type of service, patients, environment, and other variables; and the members of the team providing this service should have various skills. Second, the members of hospice providers’ team should be selected such that there is maximum cooperation, team work, and high quality service. In order to obtain better coordination and performance, a leader should be selected. One of the weaknesses of this study is that, this article is not a comprehensive review of the topic. Rather, it seeks to provide sufficient information to raise awareness of the inequity that exists in current provision of hospice care in developing countries. This is a public health issue that deserves priority among many others and we would not claim it as the most important. However, we would argue that it should not be neglected in the discussion of public health priorities. The result of this study is useful for countries who want to plan and design this service.

CONCLUSION

The need for designing and delivering hospice care service in Iran and similar countries is overtly felt considering two main factors:First, increasing load of chronic diseases such as various cancers, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and increasing population of aging population; and second, successful experience and results of hospice care in many other countries. For lack of sufficient experiences in delivering such services in Iran it seems necessary to conduct basic studies for identifying probable barriers, running appropriate preventive tasks and management, reducing the probable failures of such projects, and taking the benefits from experience of other countries. There are significant challenges against implementing hospice care in Iran such as: Need for specialized centers and huge investments in the qualification of human resources from technical and applied points of view, to deal with terminality related issues. Moreover, a change in curriculum is inevitable, considering teaching introductions of hospice care for healthcare students, especially in medical and nursing studies. This study showed that financial and cultural-religious problems of patients and their families, as well as problems of healthcare system, are main barriers against planning and delivering hospice care service. Furthermore, facilitators and suggested solutions proposed in this study would be useful in policy making of hospice care system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Finally, the authors are thankful to the participants of the study, officials and staff of hospitals, and faculties of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for their sincere cooperation.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Self-care behaviour of patients with diabetes in Kashan centers of diabetes. Q J Feiz. 2008;12:88-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nursing experience and the care of dying patients. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:97-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Continuous care in the cancer patient: Palliative care in the 21st century. Rev Oncol. 2004;6:448-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrating palliative care into heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:374-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians beliefs and attitudes about end-of-life care: A comparison of selected regions in Hungary and the United States. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:76-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- District nurses’ role in palliative care provision: A realist review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1167-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurses attitudes and practice related to hospice care. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35:249-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospice and primary care physicians: Attitudes, knowledge and barriers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:41-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing data generation and management strategies. In: Streubert-Speziale HJ, Carpenter DR, eds. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. 4. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. :35-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes and knowledge of Iranian nurses about hospice care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:209-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative research in medical education, Part 2: Qualitative research process. Res Med Sci Educ. 2012;3:64-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care for older people – exploring the views of doctors and nurses from different fields in Germany. BMC Palliative Care. 2009;8:7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Death and dying in the US: The barriers to the benefits of palliative and hospice care. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:595-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lost to follow-up: Ethnic disparities in continuity of hospice care at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:603-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives of cardiac care unit nursing staff about developing hospice services in Iran for terminally ill cardiovascular patients: A qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:56-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnic differences in the place of death of elderly hospice enrollees. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2209-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care services in the community: What do family doctors want? J Palliat Care. 1999;15:21-5. Summer

- [Google Scholar]

- Educational needs of general practitioners in palliative care: Outcome of a focus group study. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20:28-33. Spring

- [Google Scholar]

- General practitioners (GPs) and palliative care: Perceived tasks and barriers in daily practice. Palliat Med. 2005;19:111-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- General practitioners’ attitudes to palliative care: A Western Australian rural perspective. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1271-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- I'm not ready for hospice: Strategies for timely and effective hospice discussions. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:443-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparing hospice and non-hospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:238-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medicare cost in matched hospice and non-hospice cohorts. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:200-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Government expenditures at the end of life for short- and long-stay nursing home residents: Differences by hospice enrollment status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1284-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:507-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family caregiver skills in medication management for hospice patients: A qualitative study to define a construct. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:799-807.

- [Google Scholar]

- Undertaking ethical qualitative research in public health: Are current ethical processes sufficient? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38:306-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are medical ethicists out of touch. Practitioner attitudes in the US and UK towards decisions at the end of life? J Med Ethics. 2000;26:254-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences, knowledge, and opinions on palliative care among Romanian general practitioners. Croat Med J. 2006;47:142-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurses’ use of palliative care practices in the acute care setting. J Prof Nurs. 2001;17:14-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Process evaluation of an educational intervention to improve end-of-life care: The Education for Physicians on End-of-Life Care (EPEC) program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2001;18:233-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The issue of death and dying: Employing problem-based learning in nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. 2002;22:319-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bereaved hospice caregivers’ perceptions of the end-of-life care communication process and the involvement of health care professionals. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1300-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Racial, cultural, and ethnic factors influencing end-of-lifecare. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:S58-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- A strategy to reduce cross-cultural miscommunication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Acad Med. 2003;78:577-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancing cultural competence among hospice staff. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23:404-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring the success of the interdisciplinary team. Hosp Palliat Insights. 2003;4:47-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interdisciplinary approaches to assisting with end-of-life care and decision making. Am Behav Sci. 2002;46:340-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Job satisfaction: How do social workers fare with other interdisciplinary team members in hospice settings? Omega. 2004;49:327-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationships between social work involvement and hospice outcomes: Results of the National Hospice Social Work Survey. Soc Work. 2004;49:415-22.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix 1