Translate this page into:

Posttraumatic Growth in Women Survivors of Breast Cancer

Address for correspondence: Dr. Michelle S Barthakur; E-mail: m.s.barthakur@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the study was to understand the phenomenon of posttraumatic growth (PTG) in women survivors of breast cancer from an Indian perspective.

Settings and Design:

It was a mixed method, cross-sectional, and exploratory design wherein in-depth qualitative data covering a broader area of experiences were gathered from a sub-section of the larger quantitative sample (n = 50). The qualitative sample consisted of 15 Indian women from urban communities of Southern and Eastern India. Sampling method was purposive in nature.

Subjects and Methods:

Semi-structured interview schedule was developed by researchers based on a review of literature. In-depth interviews were audio recorded after their permissions were obtained and carried out at homes and offices of participants. All participants spoke English. Qualitative data were collected until no new phenomenological information emerged through the interviews.

Data Management and Analysis:

Descriptive phenomenological approach was utilized to analyze the interview data. It focuses on understanding one's life experience from the first person's point of view.

Results:

Consistent with other literature, PTG was evident in varying forms through positive changes in perspective toward life, better understanding of self, closer, and warmer relationships, and richer spiritual dimension of life.

Conclusions:

These findings have implications for promoting holistic cancer care and identifying ways to promote PTG through the initial stages of cancer care into survivorship trajectory.

Keywords

Breast cancer

India

Posttraumatic growth

Survivors

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in women with an incidence rate of 1.67 million all over the world. In India, within the last five years, as of 2012, the estimated incidence rate was 145,000, morbidity rate was 70,000, and prevalence rate was 397,000.[1] However, the number of survivors of cancer is expected to increase worldwide with the improvements in methods of early screening and treatments for various cancers.

Diagnosis of any form of cancer entails a chain of reactions and adaptations by the individual toward the diagnosis, the treatment procedures, and its side effects. In breast cancer, it starts from the time of discovery of lump or symptoms which can produce a range of emotional responses (anxiety, denial, or avoidance) depending on significance attached to the breast and perception of the lump as a threat to one's chances of survival.[2] It also requires the patient to adapt to the fast changing decisions involved around treatment procedures and its side effects.[3] In the aftermath of the treatment, one needs to adapt to the changes in body image, sexuality, one's relationships, and deal with fears of recurrence.[2]

However, research has also shown that often in the face of challenges or traumas, individuals experience positive changes commonly known as posttraumatic growth (PTG). It is characterized by deeper appreciation for life, more meaningful relationships with family and friends, recognition of increased personal strength, changes in life's priorities, and richer understanding of spiritual and existential concerns.[4]

Meta-analytic reviews on emerging research in the area of PTG with primarily cancer population revealed that the degree of growth has been reported to range from 60% to 95%.[5678] It has also been noted to be more affected by psychosocial variables of greater cancer-related stress, positive/adaptive coping, religious coping, sharing one's breast cancer experience, and for those seeking social support excepting younger age, and longer duration of time since diagnosis.[9] It has been known to act as a protective mechanism against depression and posttraumatic stress disorder.[10]

In the Indian context, studies on breast cancer have focused primarily on the epidemiological trends, awareness about its symptoms, its screening policies, genetic correlates of kinds of breast cancer and its prognosis, medical treatments and ways of improving on it, and quality of life issues. However, in the domain of psycho-oncology, rare studies have focused on coping and adapting to changes with surgery.[111213] It thereby highlights the dearth and need for research in understanding breast cancer survivorship trajectory.

The presented findings form a part of a larger doctoral study. The aim of the larger study was to understand body image, sexuality, and quality of life in survivors of breast cancer from an Indian perspective. It was a mixed method design wherein in-depth qualitative data covering a broader area of experiences were gathered from a sub-section of the larger quantitative sample. The current findings were informed by the need to understand the impact of cancer on one's perspective to life, self, spirituality, and relationships.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Sample consisted of 15 Indian women from urban communities of Southern and Eastern India. The inclusion criteria of the study were (a) women who have undergone mastectomy/lumpectomy and those currently undergoing hormonal treatment as adjuvant therapy, (b) women in the age group of 18 and above, (c) married women, (d) English or Hindi speaking, (e) minimum education up to matriculation level, and (f) at least 6 months since radiation therapy and chemotherapy courses had been administered. Exclusion criteria were (a) women currently undergoing chemotherapy or radiation treatment, (b) women with cognitive impairments, and (c) women with active or distant metastases. The sampling strategy was primarily purposive in nature.

Interview data were collected from survivors associated with two nongovernmental organizations, (a) Connect to Heal based in Bengaluru and (b) Hitaishini based in Kolkata, St. John's Medical College and Hospital, a private oncology clinic in Bengaluru, and through snowball sampling. Approval for the research study was taken from the Institute's Ethical Committee Board of NIMHANS, Bengaluru, in January 2012 and St. John's Medical College and Hospital, Bengaluru, in August 2013. Semi-structured interview schedules were developed by researchers based on a review of literature and the draft was given to seven experts whose feedback was incorporated. Before interviews were undertaken, information leaflet was provided to participants, and informed consent was taken from survivors. They were informed that there would be one-on-one interviews which would occur over 2–3 sessions, each lasting 1.5–2 h. Interviews were carried out at homes and offices of participants and audio recorded after their permissions were obtained. One participant refused consent for audio recording and therefore, detailed notes were made through the interview. After providing consent, filling out demographic and clinical data sheet and quantitative measures, interviews were started. All participants spoke English. Qualitative data were collected until no new phenomenological information emerged through the interviews.

Data management and analysis

Descriptive phenomenological approach was utilized to analyze the interview data.[14] It focuses on understanding one's lived experience from the first person's point of view. Neutrality toward the subject matter was maintained using a memo for bracketing, which focused on eliminating researcher's personal biases. The memo was maintained since conceptualization of the study through analysis and interpretation phase. It included researcher's preconceptions about the phenomena, personal experiences related to it, beliefs about the culture, hypotheses formulated during the review of literature, and through the process of data collection and biases encountered during exploration of certain aspects of phenomena.

To analyze the data, following steps were followed:[15]

-

Transcription (using InQ Scribe), proof-reading of interview, and re-reading to acquire understanding of experiences

-

Line by line reading to identify broad area of phenomena being captured

-

Statements assigned meanings to enable recognition of intricate details pertaining to phenomena

-

Codes grouped into cluster of themes and categories

-

Findings integrated into exhaustive description of phenomena and provided to other authors for review

-

Feedback of other authors was incorporated to reflect universal features of phenomena.

RESULTS

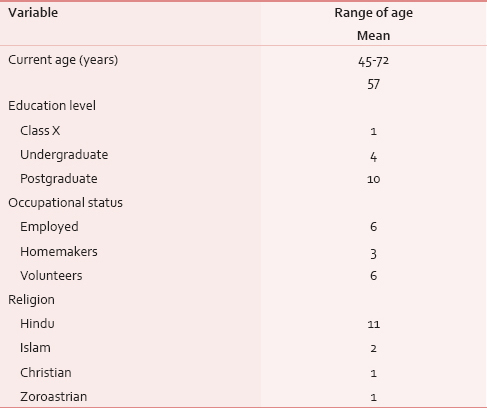

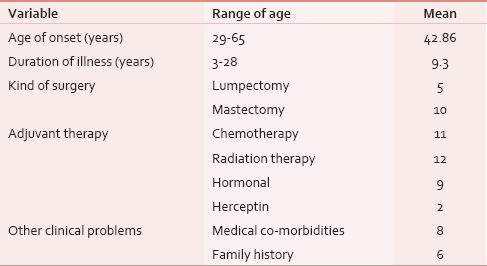

Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics are depicted in [Tables 1 and 2], respectively.

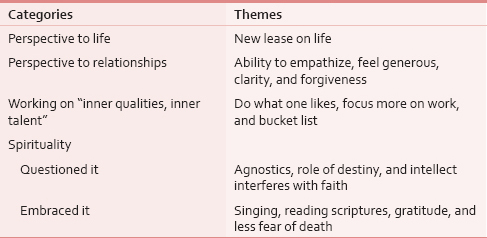

Cancer: A new lease on life

As stated in Table 3, the most common theme in terms of an increased appreciation of life was evident through the need to live in the present with the fullest capacity: “Can't be taken for granted,” “unpredictable,” “it's so short-lived,” “can't postpone,” “start accepting as it comes,” and “its bonus for me.” Themes indicating clarity about issues that were perceived as pertinent in life also emerged: “Better vision to see the answers,” “mirror which held the truth to my face,” and “little patience with pettiness.”

Self: A priority and “stronger mentally”

A recurring emerging theme highlighted a change in the need to look after one's own needs and make oneself a priority [Table 3]:

“…I have realized is that you only matter. I know it sounds so very selfish but I think selfishness is a great thing. … Itne hisson mein bat gaya hu mein ki mere hisse mein kuch bacha nahin. (I have been divided into so many parts that I have nothing left in my share) Jagjit Singh's ghazal… “Be a good daughter-in-law,” “Be a good wife,” “Be a good mother,” “Be a good something,” Nobody told me to be a good me… this illness to a large extent made me realize that I have to be selfish. I have to find my own answers. I have to live my own life, I have to be happy, the world be damned. Honestly! (Laughs) but ironically it takes a lot of journey to realize this.”

Another recurring theme revealed that the survivors felt stronger mentally and confident with the view that if one could survive through cancer, one could survive anything in life:

“I think I have become more mature, more stable, more confident if at all that is possible. I have become more accepting and actually to an extent, I have become more shameless… earlier I wouldn't talk about the female anatomy as easily as I do now. Today I can stand up before five hundred people and say to people “I have breast cancer,” otherwise earlier using the word breast itself was a big challenge.”

Another theme focused on the need to engage in meaningful activities (vacations, nurturing talents) that made one feel happy about oneself through being “conscious of a Bucket List:”

“I do remember to take holidays at least 2 times a year… I don't care if I don't make money. … I am now well so I can go. I almost was dying so I should go … if God has brought me through this, it means that I should see more of the world … So, but yeah, I think it's basically I feel very blessed and in a very narrow sense, very shallow sense it's my claim to fame.”

In relation to occupational work, few survivors stopped working and opted to pursue activities based on what they enjoyed: “After this disease, all my inner qualities, inner talent comes out and I used to act.... Everything I'm doing, even creative works and I'm writing some funny dramas and I act in this and I got lot of prizes, only after this disease.”

Relationships: Closer, more empathetic, and generous

As seen in Table 3, the most common theme in terms of relationships was an increased ability to empathize with others: “Previously I used to see the bad side of others now I realize that everyone has got something positive within them” and accept others the way they are: “…I was able to understand that I had to think about myself and accept people's relationship to me in whatever form, shape, or size they want to do it and I won't let that affect me.”

Other changes included the ability to feel generous: “I think I have become more generous in my understanding and generous in giving my things also to people. … I feel when I am not using this and it is of no use, no point in hoarding things, it's nice to give things to people…” It also enhanced clarity in relationship in terms of the ability to “make out between friends and nonfriends.”

A variant theme was about the capacity to understand whether one could forgive another for a perceived wrong: “If I'd done wrong by cutting her off, I mean I would realize it when I had cancer and I would make amends but so when I didn't feel like many amends or moves towards her, I said,” It's okay.” At this stage of my life, when I don't want to then it's okay. I probably did nothing wrong…”

Spirituality

The journey of cancer brought each survivor to contemplate on the spiritual dimension of life. However, it differed for each individually in terms of the impact it had on their levels of faith and the ways they chose to make meaning of it [Table 3].

One survivor who was also a volunteer at a palliative care center believed she had become an “agnostic,” though she appeared to hold the need to serve and work for humanity:

“... My exposure to (palliative care home) has made me wonder is there anything as a merciful God sitting there because I see children suffering that makes my heart go? I just can't take it… People say God's testing you but why make that small child suffer. One child came with a big growth with maggots… His mother is crying, howling, begging us, “Please see the child dies.” … sometimes terrible tragedies like one widowed mother, 20-year-old son, all hopes on him, doing manual work and all those things and educating him. And he has come to die with leukemia. … but of course I have full faith in humanity. I love people. I would love to do something for them… I believe in humanity and of course our religion also says if you serve humanity, you are serving you. Work is worship and all those things so I believe in that.”

Themes about the role of destiny emerged: “What is going to happen is going to happen.” or the beliefs about doubt in ability to have faith in a higher power:

“Strangely, it made me think a lot about Him but sadly, it didn't give me any faith… because I suddenly begin to rationalize and I begin to intellectualize everything. I say, “Fine if He has given us this. I suppose He's got a reason for it. He wants me to suffer. He wants me to find out some reasons and answers or something.” And I tend to intellectualize. Intellectualism and faith don't go together …. I would have thought that this kind of illness should take you closer to God make you feel, “God please make me well, please make me well.” I don't remember ever praying to Him … yes when it was extremely painful, I said, “God take away my pain. I want to die.” I prayed possibly for death.”

At the other end, there were survivors who also felt more drawn toward a higher power. It manifested itself in various forms such as singing: daily one-one devotional song I am learning in my music class. Teaching music and learning music is only a big thing and then being involved in that. While praying, just you are praying to Saraswati, that Saraswati (Hindu Goddess of knowledge) should come in your mind, about her dress, about her blessings....”

Few survivors' themes suggested reading religious texts and finding answers to their questions about life and faith in God through them:

“… there were some of the things in the Bible which… it is like as if every word was meant for me, every assurance was meant for me, every promise meant for me so I held on to those… So my knowledge of the Bible and God's word has really really grown so much that, that is the source of strength for me … it makes you feel that you can trust the word of God and things can really change because I have seen so many such things happening in my life. So there was a situation and I think God allowed me to go through that situation so that I would know him in a better way and, you know, trust my life…”

Themes about gratitude also emerged, especially when survivors had accomplished more than the expected norm for the respective culture: “ I am from a Muslim family and my age people, very few have really studied this well you know doing postgraduation and doing so well in life. And everything for me…God has been very very kind to me like everything went on thak thak … God just want to test me…like you know… see I have given you all these things are you really grateful about it? So I wanted to tell in written that yes I am very grateful…” In relation to it, the theme “He is not a punisher. God is something, He is epitome of love and forgiving” also emerged.

Regarding questions of life and death, spirituality helped few survivors find strength through it: “Sufism always helped me so that way I have always felt… life and death, they are two sides of the same coin… Once a person is born the very surest thing going to happen is death… In Koran also it says that every living being has to taste death. So for me death is not something…not very scary …for me preparation is being good to myself and to other people as far as my knowledge goes, I don't want to do something intentionally harmful to other person … I feel there is God and He knows the best, how to take care … death is like crossing from one room to the other and that room may be something different from the one you are staying in right now. So that was always my concept. So it didn't rattle me off like what happens if I am going to die, nothing happens when I die.”

DISCUSSION

The reported findings of the article form a part of a larger doctoral study. The phenomenon of PTG was evident in varying degrees in each survivor in each of the domains: Life, self, spirituality, and relationships.

In terms of changed attitudes toward life and self, the PTG process has possibly been influenced by the identity of an Indian woman's role primarily as a mother or spouse which can tend to supersede all other aspects of her identity (e.g., professional). With this as a background, themes of PTG revolved around the re-prioritizing of one's own needs as taking precedence over needs related to other roles (e.g., spouse, mother, and professional). Moreover, changing nature of the Indian society wherein women's emancipation movements are at its forefront and characteristics of the current sample (high levels of education, employment status as professionals or cancer volunteers, young age of onset, and higher number of years since diagnosis) could have influenced the PTG process. Research has similarly revealed that PTG is influenced by greater cancer-related stress, positive/adaptive coping, religious coping, sharing one's breast cancer experience, and for those seeking social support, younger age and longer duration of time since diagnosis.[910]

In terms of spirituality and existential concerns, the varying themes reveal that the event influenced each survivor to contemplate on one's spiritual beliefs thereby leading to the evolvement of a new understanding of its role in their lives. Studies have shown that spiritual beliefs are an intimate and important dimension of PTG contributing to the overall quality of life.[1617]

The shortcomings of the current study include (a) sample size consisted primarily of survivors from urban, educated, and moderately financially-stable families leading to exclusion of rural survivors; (b) due to stigma attached to cancer, it could give rise to the possibility of self-selection bias thereby rendering it inaccessible to obtain information from those feeling stigmatized; (c) quantification of PTG phenomenon in the current study has not been done as it was not a primary aim of the study. However, the perchance revelation of evident PTG in the population provides us the understanding that PTG as a phenomenon does occur in India as it does in its Western counterparts. Second, the qualitative nature of the study provides us with insight about the kind of PTG that can tend to occur.

The clinical implications of the study include: (a) Need to actively identify coping process through the early parts of treatment process, (b) the survivor's attitude toward the illness, and (c) meanings attached to the occurrence of the event. These processes can contribute to identifying and setting in process PTG as an attempt to rebuild the survivor's shattered assumptions about the world (world is benevolent and meaningful, self is worthy).[918] In consistence with other studies, it suggests that active coping (problem focused), spiritual coping, and the social support, especially from spouse followed by family and other survivors plays an important role in the process of PTG.[192021] It is, especially important in the context that it can influence a survivor's overall physical and mental quality of life. Interventions using mindfulness-based approaches have been seen to promote PTG as well.[22]

CONCLUSIONS

Future research needs to identify the process involved in PTG: The cognitive style and behavioral thoughts that promote it, and the environmental factors influencing the survivorship trajectory, especially in the Indian context. These findings will have an important role to play in the holistic cancer care approach.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 2015. Globocan.iarc.fr. Fact Sheets by Cancer. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx

- Psycho-oncology. In: Chen LM, McChargue DE, Collins FL, eds. The Health Psychology Handbook: Practical Issues for the Behavioural Medicine Specialist. California: Sage Publication; 2003. p. :325-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-traumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15:1-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-traumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:343-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth in breast cancer patients – A systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:641-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: Patient, partner, and couple perspectives. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:442-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Personal growth and psychological distress in advanced breast cancer. Breast. 2008;17:382-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth in adult patients undergoing treatment for acute leukemia. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:13-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- The interaction of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psychooncology. 2008;17:948-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial disorders in women undergoing post-operative radiation and chemotherapy for breast cancer in India. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47:296-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psycho-oncology research in India: Current status and future directions. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2008;34:7-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of coping skills and body image: Mastectomized vs. lumpectomized patients with breast carcinoma. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:198-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Logical Investigations. New York: Humanities Press; 1970.

- Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In: Valle RS, King M, eds. Existential Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology. New York: Plenum; 1978. p. :48-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer patients: A qualitative phenomenological study. MEJC. 2012;3:35-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shattered Assumptions. New York: The Free Press; 1992.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Women Health. 2012;52:503-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Promoting post-traumatic growth in people with cancer. Occup Ther Now. 2014;16:23-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- A nonrandomized comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction and healing arts programs for facilitating post-traumatic growth and spirituality in cancer outpatients. Support Care Cancer. 2007;21:1038-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does self-report mindfulness mediate the effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on spirituality and post-traumatic growth in cancer patients? The Jouranal of Positive Psychology. 2015;10:153-66.

- [Google Scholar]