Translate this page into:

Role of communication for pediatric cancer patients and their family

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Communication is a key component in medical practice. The area of pediatric palliative care is emotionally distressing for families and healthcare providers. Inadequate communication can increase the stress and lead to mistrust or miscommunication.

Materials and Methods:

Reviewing the literature on communication between physicians, patients, and their family; we identified several barriers to communication such as paternalism in medicine, inadequate training in communication skills, knowledge of the grieving process, special issues related to care of children, and cultural barriers. In order to fill the gap in area of cultural communication, a study questionnaire was administered to consecutive families of children receiving chemotherapy at a large, north Indian referral hospital to elicit parental views on communication.

Results:

Most parents had a protective attitude and favored collusion; however, appreciated truthfulness in prognostication and counseling by physicians; though parents expressed dissatisfaction on timing and lack of prior information by counseling team.

Conclusion:

Training programs in communication skills should teach doctors how to elicit patients’ preferences for information. Systematic training programs with feedback can decrease physicians stress and burnout. More research for understanding a culturally appropriate communication framework is needed.

Keywords

Communication

Counseling

Cultural

Palliative care

Pediatric oncology

Stress

INTRODUCTION

Communication is a very important part in medical practices. It is required to inform the patient about the disease, treatment, prognosis, course of illness, and complications; in case of a terminal disease—what to expect, options, and time left. This communication helps to allay fears of the unknown and provides empowering information. It ensures that the patient and the treating and/or palliative care team have a clear understanding of the goals and course of action. As the patient and family require repeated reassurance, this communication has become synonymous with counseling. A term which aptly describes this interaction is ‘collaborative communication'.[1] In most cancer centers the physicians undertake this communication/counseling themselves; a few centers also have psychologists to provide additional counseling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After informed consent, 25 consecutive parents of pediatric cancer patients in the age group 1–14 years were interviewed. All the children were on treatment for their disease at our hospital for at least 6 months (range 6–38 months), all children in the study group had acute lymphoblastic leukemia. They were administered a simple questionnaire which had been formulated according to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, parents were interviewed together, without the child being present.

Questionnaire

Are you interested to deliver diagnostic information to child?

-

1. Yes

-

2. No

Are you interested to know child's decision about the treatment?

-

1. Yes

-

2. No

Are you interested to deliver all the information about the side effect of therapy to child?

-

1. Yes

-

2. No

RESULTS

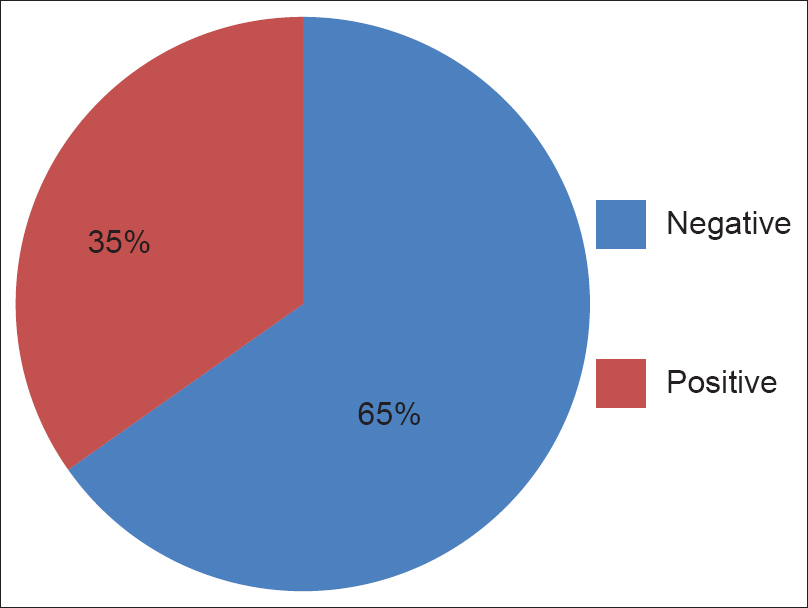

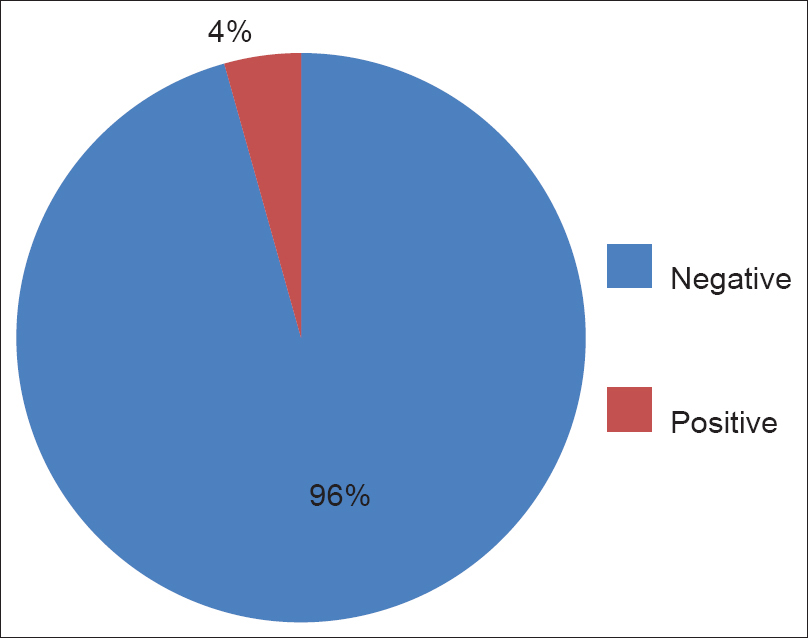

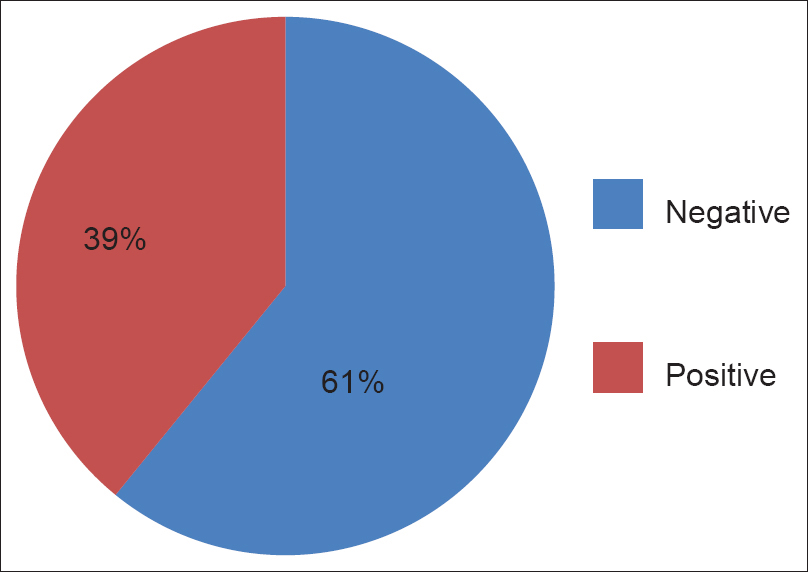

All parents consented to the study. Two families did not complete the study; as the child died and in other, the family opted for alternative medical treatment, both families refused to complete the interview and were excluded from the study, hence 23 interviews were completed and analyzed. Majority of the families had shown the negative response related to delivery of diagnostic information to child (65%, 15/23), though it was encouraging to see at least 35% had been open to informing the child about their diagnosis Figure 1. Though almost all (96%, 22/23) felt the child should not make any decision about the treatment Figure 2. Majority (61%, 14/23) felt the child should not even be informed about side effects of therapy, and especially about long-term effects Figure 3. If the diagnosis, prognosis, and other information was to be told to the child, 100% preferred that the doctors to give the information to the child. Though they all approved of the amount and content of information given to the child, only 21% (5/23) were satisfied with the timing or manner it was delivered. The parental reservations were that they had not been given sufficient prior knowledge of what was to be done (counseling) and would have liked additional time to prepare themselves and would have wanted the information to have been given to the child at a later date (after treatment started and not before as done by physicians).

- Family's response related to delivery of diagnostic information to child

- Family's response related to child's decision about the treatment

- Family's response related to delivery of information about the side effect of therapy to child

Palliative care was a difficult concept to explain and only three families were receiving palliative care at the time of administration of the questionnaire. In these families both child and parent were aware of the prognosis, but the parents felt that they would have liked to have shielded their child from the knowledge if possible. Deciding when to stop curative treatment, when such treatment was futile, was a hypothetical question that was posed to the families. The parental responses showed that the decision was mostly the domain of the parents—20 felt only parents should decide, seven doctors alone, four families stated that both the doctor and parent should decide, and none of the parents felt the child should take part in this decision-making process.

DISCUSSION

The study reinforces the already observed parental belief in the traditional paternalistic role of the physician. These families were not under acute psychological stress; but in some cases even with greater than 3 years of therapy, they were still finding it hard to communicate about cancer to their children. Parents of children with cancer are very unwilling to have the news broken to the child and tend to delay the process as much as possible. They do not wish to involve the child in any deliberations for treatment or palliation.

Indian parents want to shield and protect their children from the knowledge of cancer, as shown by their desire to delay the child's counseling to after treatment starts and avoid unpleasant discussions on prognosis and side effects, this is an important cultural response, and the physicians need to be aware of it. The treating team needs to forge an alliance with the family to facilitate communication and give the parents time to cope with their own fear and anxiety.

Limitations of the study

It did not take the individual parent (mother/father) views, but decisions are usually taken by the parents together in Indian families and the dominant view is what realistically happens, hence we felt it gave the actual situation. We did not study the child's viewpoint in this pilot. Counseling needs are largely unmet and many more studies to provide communication guidelines are required. Better communication with the family to elicit how they would like to receive information will be a useful and important tool for physicians and counselors.

CONCLUSION

It is important for healthcare providers to give information in clear and local language and explain things according to the needs of the patient and if the patient is a minor, as per the parents’ preferences. A middle path is required in breaking news. First information is to be given to the family, then gradual discussion of the disease and options with the patient, while providing hope, whenever the patient is ready for communication. In terminal cases the hope is for support, comfort, and relief of pain.

The training programs in communication skills should teach doctors and healthcare providers how to elicit patients’ preferences regarding communication of information. Despite workshops being effective in changing key communication behaviors, it is not certain how much of what is learnt is applied to clinical practice as pointed out by Maguire.[23]

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Collaborative communication in pediatric palliative care: A foundation for problem solving and decision making. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:583-607.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breaking bad news: Explaining cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Med J Aust. 1999;171:288-9.

- [Google Scholar]