Translate this page into:

The Impact of Breast Cancer on the Patient and the Family in Indian Perspective

Address for correspondence: Ms. Annie Alexander, Division of Molecular Medicine, St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru - 560 034, Karnataka, India. E-mail: annie@sjri.res.in

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Purpose:

To understand the role played by the immediate family in treatment decision and support in patients diagnosed with breast cancer, the influence of demographic factors on psychosocial roles of women within the family.

Methods:

A mixed method design used for data collection on family support, financial arrangement and psychosocial impact of cancer from 378 women with breast cancer recruited at first diagnosis between 2008 and 2012, during multiple counseling sessions. The median follow-up is 7 years with only 2% lost to follow-up.

Results:

Most patients (99%) had support from family members. 57% of patients met the costs of treatment through personal savings and health insurance. The rest (43%) had difficulty and had to resort to desperate measures such as selling their property or taking on high-interest personal loans. Patients with higher education and urban settings had better financial management. A male member of the family (husband or son) was the main decision maker in half of the cases. Concerns over women's responsibilities within the family varied by the age of the patient. The vast majority of women (90%) experienced social embarrassment in dealing with the disease and its aftermath.

Conclusion:

In India, it is the family that provides crucial support to a woman with breast cancer during her ordeal with the disease and its treatment. This study has implications on the psychosocial support beyond the cancer patients alone, to include the immediate family and consider aspects of finance and social adjustments as critical in addition to the routine medical aspects of the disease.

Keywords

Breast cancer India

family

financial stress

psychosocial

social embarrassment

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of breast cancer in urban Indian women has been increasing steadily, and it has now surpassed cervical cancer to become the most frequently diagnosed cancer in this population.[1] Distressingly, the 5-year cumulative mortality remains unacceptably high at 50%, primarily due to a late-stage presentation.[2]

Breast cancer has an impact on the psychological and social well-being, not only of the woman affected but also on her immediate family members. In Indian culture, the family remains the dominant social unit despite a gradual shift in the focus on to the individual in more recent times, especially in urban settings. The individual and the family are closely interlinked financially and socially in all their activities.[34] Hence, immediate family members are closely connected, and experience challenging emotional situations as though they were personally affected. This aspect has been noted and commented upon previously in the setting of breast cancer in Indian women.[567]

In spite of the rapid growth of health-care delivery systems in the private sector, particularly in urban settings, universal health cover for cancer is still a distant dream.[8] Though there have been notable economic growth over the past couple of decades, India is still a member of the low- and middle-income countries group of emerging economies. Most middle and lower class families lack health insurance and have to find the resources for treatment by paying out-of-pocket.[5]

On the social front, the organization of most families is still patriarchal and hence Indian women are often perceived to be subordinate to men regardless of whether they are from rural or urban areas, educated or uneducated, employed or not.[910] Hence, a significant proportion of Indian women rely on their husband, father or son for making decisions that concern their bodies and lives. This is a striking contrast to the approach of emancipated women in high-income Western societies.[6]

A woman is expected to play different roles as daughter, wife, mother, or mother-in-law based on the context. During the time of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy), her ability to fulfill these roles and responsibilities are severely impacted.[1112] Due to the treatment and its side effect, the patient has to deal with multiple issues such as disfigurement of her body, sexual intimacy with the husband, and the ability to care for her children.[131415] This leads to psychological disturbance, 38% of the cancer patients are identified with anxiety and depression, and also to distress, adjustment disorders, delirium and posttraumatic stress disorder.[16]

A considerable literature has focused on the demographic and psychosocial issues of cancer in an Indian setting. The specific roles and responsibilities played by the immediate family members through the process of diagnosis and treatment including financial stress are not clearly examined in a large sample size. The objective of the study is to be examined and explored the financial burden and mechanisms of coping with financial stress, involvement and support, role in decision-making by the immediate family members including the psychosocial aspects of women's role within the family, in patients diagnosed with breast cancer over the complete course of treatment.

METHODS

Data was collected from an observational study over a period of 9 years from June 2008 to June 2017 using a mixed method of descriptive survey and a phenomenological approach at the Nadathur laboratory for breast cancer research, St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India. 378 breast cancer patients were enrolled based on the inclusion criteria of biopsy confirmed primary breast cancer in women 18 years or older, and all stages of breast cancer who had sought care at one of two centers (1) St. John's Medical College Hospital (n = 139) and (2) Rangadore Memorial Hospital (RMH) (n = 239) were included. The patients enrolled at the RMH were subsequently transferred to a sister concern, Sri Shankara Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, a dedicated cancer hospital, where they were followed-up.

Procedure

Recruitment was based on a consecutive series of breast cancer patients who presented at the two hospitals for evaluation of a breast lump. The oncologist referred all newly biopsy-confirmed patients to the researcher prior to starting the treatment (surgery or chemotherapy). This study was approved by the ethical review boards of both hospitals involved. Informed consent was obtained from all patients to ensure that they understood the goal of the study and agreed to have long-term clinical follow up for at least 5 years. All contact information including phone numbers of the caregivers was collected and maintained confidentially. Each of the recruited patients was personally contacted (on average 10 contacts) during hospital visits for treatment-surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. After that, they were contacted in person or telephonically (on average 18 contacts). A breast cancer support group termed “Aadhara” (meaning “support” in the local language Kannada) was formed to address multiple issues as well as conduct group contact sessions. On an average, ten individual counseling sessions were held for patients and immediate caregivers during which time information about disease perceptions were collected. Data was collected during the initial sessions on financial arrangement, members of the immediate family involved in support, decision-making for treatment and psychosocial aspects of the impact of cancer diagnosis. Information on family bonding and prioritization of self-health were collected during follow-up sessions. Support was provided through counseling lasting at least 30 min with empathetic listening techniques and approaches such as psycho-education, supportive psychotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy to increase hope and cope with illness.

Measures

378 patients were recruited using purposive sampling technique for a descriptive survey to measure demographical and clinical variables like age, education, geographic region, occupation, marital status, health insurance, primary caretaker's information, date of diagnosis. Psychosocial variables were:

-

Family support and bonding

-

Source of money for treatment–Patients were sub-categorized into groups based on the level of difficulty as outlined below:

-

None; costs covered by insurance

-

Mild; when treatment costs were met from their savings

-

Moderate; when funds were raised by mortgaging gold ornaments or land or selling such assets

-

Severe; when only personal high-interest (>36% p.a.) loans were the source; or they were not able to find the money and discontinued therapy.

-

-

Decision making for the treatment (self, husband, son, daughter and others)

-

Concern regarding the women's role and responsibilities affection toward children-schooling, employment and marriage, the health of the spouse and dependent parents

-

Social embarrassment

-

Prioritizing their personal health

-

Support by the family in life after cancer.

Patients and their family members who participated in descriptive survey and were expressive about their disease, were included for a qualitative approach to understand the phenomenon. Using a random sample technique, an approximate of 10% of the sample (n = 40) underwent a semi-structured interview focusing on their psychosocial challenges in facing breast cancer.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate demographic, clinical, psychosocial variables which are calculated as proportions. Difference between categorical variables was analysed by Chi-square tests. All P < 0.05 were taken as significant. XLSTAT software for MS Excel (2017), Addinsoft, USA was used for all statistical analysis.

Qualitative analysis

All the interviews were noted down at the end of the session and were transcribed by the study counselor (AA). Thematic analysis was done on 40 patients by two members (AA and RK) independently who analyzed the notes manually using line-by-line coding. Through the coding emerged the themes and illustrative quotes. In case of divergence of opinion, the consensus was arrived by both the study counselors. Data source triangulation (patient and family members across the interviews) and methodological triangulation (qualitative + quantitative) were tested to check the validity of the findings.[1718]

RESULTS

Description of cohort

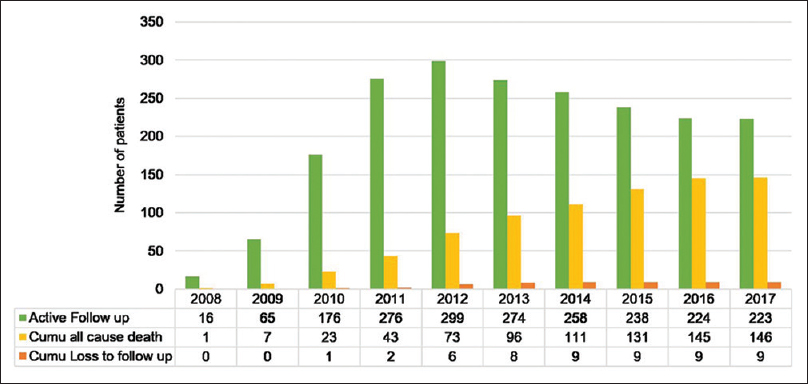

We approached 404 breast cancer patients, amongst whom 26 patients refused to participate in the study because they did not want to be in touch with the counselor over an extended period. The recruitment was done between June 2008 and May 2012. The median age of the patients at first diagnosis was 55 years. All the participants were followed up from the date of recruitment till their death or till the end of the study on 30th June 2017. The overall median follow-up was 7 years, the maximum was 9 years and minimum follow-up period was 5 years [Figure 1].

- Recruitment, mortality and follow-up.

Amongst the 378 patients enrolled in this study, 38% (146/378) patients expired over the duration of the study. 32% (122/378) patients expired due to breast cancer, 6% (24/378) due to other co-morbidities and old age. 36% (137/378) patients had developed recurrence/metastasis.

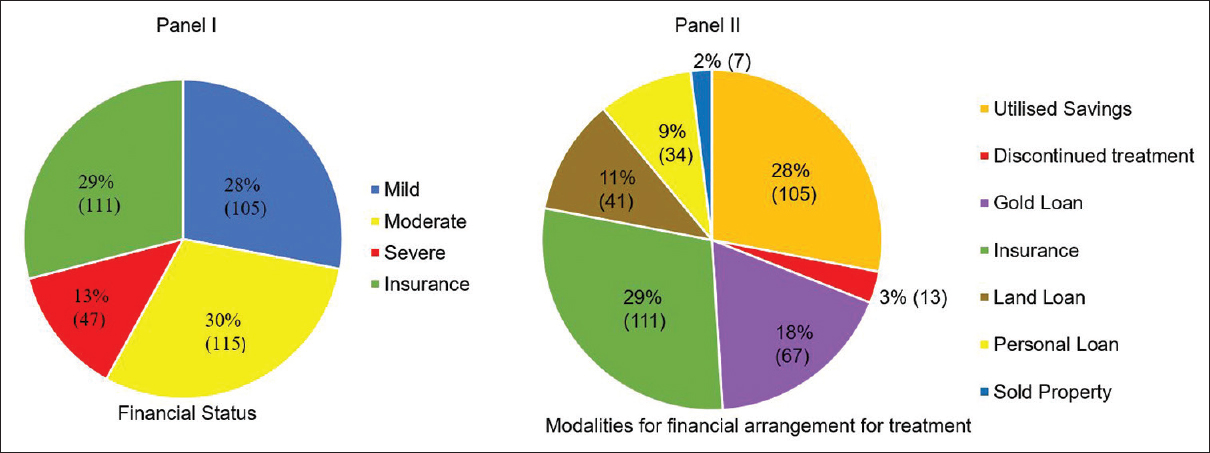

Cancer diagnosis poses a significant financial burden on family

In a country with no universal national health scheme to provide treatment for cancer, the financial burden is mostly absorbed by the family. Only 29% had medical insurance to cover the cost of treatment. This was often through the insurance schemes purchased by the patient's spouse or children. Figure 2 shows the segregation of patients into 4 groups based on the degree of financial stress. 57% of the patients managed to raise all the funds necessary and completed the entire prescribed treatment. 30% had moderate levels of difficulty in finding the resources for treatment and had to resort to measures such as selling their properties, mortgaging their gold ornaments and/or land (30%). 13% had severe difficulties, of whom (10%) resorted to high-interest personal loans and a very small proportion (3%) discontinued the treatment since they were unable to find any means of financial support.

- Degree of financial stress and sources of money for treatment.

We examined the association between the availability of financial resources and sociodemographic factors (education, urban background and employment). Amongst those with adequate financial resources, the significantly higher proportion of patients were with higher education (68% vs. 32%, P < 0.0001), from urban background (62% vs. 38%, P < 0.0001) and those who were employed (66% vs. 34%, P = 0.02).

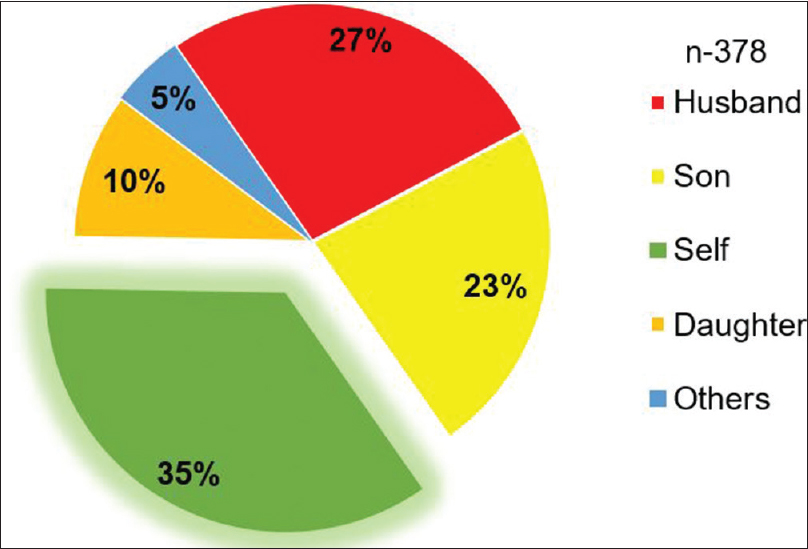

Decision on treatment is made predominantly by males in the family

The organization of the Indian family whether joint or nuclear is still largely patriarchal and women continue to be dependent on male members of their family for decision-making. Figure 3 shows a male member of the family (husband/son) was the predominant decision maker in half (50%) of all cases. A small but significant minority of women (35%) made their own decisions, and most of these women were educated (85% 114/134) and employed (53% 71/134).

- Relationship to patient of family members who made treatment decisions.

In the overall decision making for treatment, two-thirds of the cases (65%), the decision on treatment options was made by immediate family members including husband (27%), son (23%), or daughter (10%) and other relatives (5%). As expected, patients with lesser education (85% in primary of lesser educated vs. 15% in higher educated, P < 0.001) and homemakers (77% in homemakers’ vs. 23% in employed, P < 0.001) were more dependent on the family members for treatment decision-making.

The immediate family was a major source of support

We collected information about members of the family who were the caregivers during treatment. Most of the care was provided by the immediate family members including husband/parents/siblings amongst younger patients, whereas it was children in the case of older patients and even grandchildren in the case of those older than 70 years. Almost all our patients (99%) had family support. One percent of the patients who didn’t have family support were mostly single, widows or separated from their husband. A patient who had been widowed stated, “It has been difficult for me in managing work and treatment as I live alone. I don’t have a family to support me through this.”

During the follow-up post treatment spanning as long as 9 years, support and care were predominantly provided by immediate family members. In 96% of the patients who remained in touch post complete treatment, there was strong “family bonding.” This emerged from thematic analysis during the time of treatment, and it also led to an improved understanding among the members of the family.

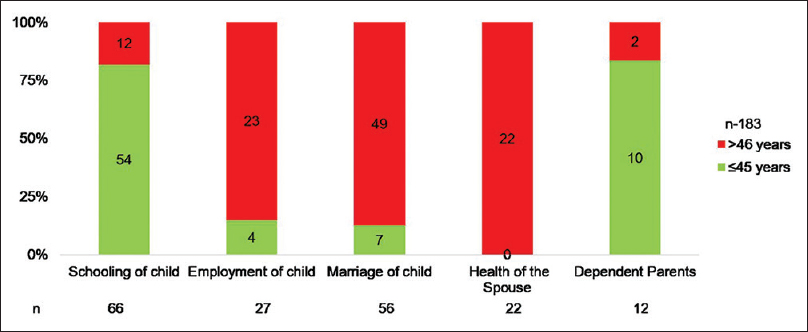

The psychological impact of cancer diagnosis on the role of women in the family

Half of all of our patients expressed concerns related to their ability to fulfill their role as a mother, spouse or daughter. Specific issues mentioned were those of children being school-going, not yet married and not being employed [Figure 4]. And followed by concerns about the health issues of their husbands and dependent parents. We used the age of 45 years as a cut off for categorizing women as young. This was chosen instead of the nationally accepted cut-off of 40 years because of the higher median age of our cohort. As seen in Figure 4, younger patients had higher concerns about the schooling of their children and providing care to dependent parents, while women over the age of 45 were concerned about the health of their spouses and the employment and marriage of their children.

- Concerns regarding specific responsibilities of patients stratified by age.

Cancer diagnoses is still a taboo in social circles for family of patients with cancer

Indian society thrives on social gathering for festivities and celebrations. Social embarrassment due to disfigurement by cancer was one of the themes expressed by most of our patients. The vast majority (90%; 311/347) of our patients admitted to avoiding social gatherings and interactions.

As can be seen in Table 1, the sense of embarrassment was present in both young and the old. None of the factors such as having a college education, being employed and residing in an urban setting seemed to make any difference as far as the sense of social embarrassment was concerned.

| Variable | n=311 (%) | Social embarrassment |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤45 | 80 | 77 (96) |

| >46 | 267 | 234 (88) |

| Education | ||

| >High school | 239 | 211 (88) |

| Primary and lesser | 108 | 100 (93) |

| Background | ||

| Urban | 280 | 251 (90) |

| Rural | 67 | 60 (90) |

| Occupational status | ||

| Employed | 99 | 85 (86) |

| Home maker | 248 | 226 (91) |

Cancer survivors value their health more after cancer

Post-treatment, >90% of patients prioritized their general health by being regular with the follow-up, with an emphasis on exercise and diet as well. Virtually all of them were aware of the probability of cancer recurring. Most of the patients were on regular follow up with their clinical care providers and were getting all of the mandated investigations (e.g., annual mammogram) done. Throughout this follow-up period, 54% of family members of the patients continued to be supportive and involved in the patient's well-being. In more than a quarter of the cases, it was the patient's husbands (27%) who were closely involved after the treatment by prioritizing the health of their spouse. A patient's husband stated, “She forgets her appointments, but I make sure that she does not miss her regular clinical follow-up, and gets her annual investigations done.”

The verbatim records of the semi-structured interviews with the patients were utilized as much as possible in arriving at the themes [Table 2]. The central theme that emerged was the pivotal role played by the immediate family in coping with the disease. The other recurring themes concerned the sources of finance for treatment, the nature of decision-making, with a dominant role by male family members, the concerns of the patient in fulfilling her social and family roles, her sense of social embarrassment and finally her move toward prioritizing her health with the support of the family.

| Themes | Codes and illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Financial arrangements for treatment | 1. Financial sufficiency |

| Health insurance - “….Because of my son’s office insurance, I can get the treatment, not worrying much about the treatment cost” | |

| Savings - “During cancer treatment, whether you’re rich or poor, to arrange for the finance at short notice becomes difficult, we had to break our fixed deposit” | |

| 2. No financial sufficiency | |

| Sold the properties or mortgage their gold ornaments or land - Husband stated: “I had to pledge her gold to get the treatment money.” “We had a piece of land for farming, a portion of which we had to sell for her treatment” | |

| Borrowed money - Husband, stated “It was a sudden miserable condition for us, we didn’t have any assets as to use for her treatment, so I had borrowed money for a high-interest……which I am repaying still | |

| Discontinued the treatment - Son stated “….I get daily wages doing some small work that would be only enough for food. How could I get this huge amount for her treatment? So, we stopped her chemotherapy” | |

| The person making the treatment decisions | Males in the family - “I let my husband decide on my treatment choices because he is the head of the family and takes most of the decision at home.” “…My son is educated; he knows about all this, so I allowed him to take the decisions.” “I trust my family. They are the ones who wish the best for me….so I ask them to take decisions on my treatment” |

| Self - “….I am glad that my company insurance cover is paying for my treatment, so I am not dependent on my family for finance during this phase” | |

| Family support during treatment | Family support - “Without my family, I wouldn’t have been able to manage this situation.” “Cancer is a long-term treatment…. It does not get over with few visits to the doctor nor is one able to take the medication at home; rather it requires multiple hospital admissions for chemotherapy, and daily visits during radiation….one of my family members accompanied me thought out this time.” “My family members were supportive of my physical inabilities during this time I couldn’t get involved in my routine household work due to the emotional instability of my situation |

| Concerns regarding the disease as a role of women in the family | Schooling, employment and marriage of child - “My child is still in the school; I need to be with him to see him grow, and attend to his needs.” “My son has finished college but still not yet found a job, I need to support him,” “I have two daughters; I need to get them married. With this sickness and expenses, I don’t know how I will be able to do so” |

| Health of the spouse - “My husband has a neurological problem, so he relies on me for most of his work, now if I am ill how he will manage” | |

| Support for dependent parents - “I have an old parent who is staying with me, I don’t know how I will take care of them” | |

| Social impact of diagnosis | Social embarrassment - “With my hair loss, it is difficult to attend social gatherings, as people wanted to know about my reason for hair loss and it is difficult to explain to all.” “In a marriage function, I would stand out from the crowd because of my bald head. Everyone who approaches me would want to enquire about my illness.” “I preferred going to a small temple for Pooja, which is close to my house. So, I get a peaceful time” |

| Prioritization of self-health | Regular clinical follow up - “…As the oncologist advise I do come once in 3 months for an OPD visit and annually get a mammogram” |

| Exercise and diet - “I go for my walk every day, even if there is a function at home.” “I do my exercise 5 days a week and watch on my weight” | |

| Support by the family in life after cancer | Family Bonding - “The cancer treatment brought my husband and me closer, where we had more time to each other in reflecting on our relationship through this challenging phase.” “After this episode of cancer, my daughter calls me every day to enquire about my well-being” |

| Family involvement - Husband stated, “She forgets her doctor visiting dates, but I fix the appointment with the doctor for her regular clinical follow-up and get her annual investigation done” |

OPD: Outpatient department

DISCUSSION

The dominant narrative in the impact of breast cancer on women which has emerged from economically advanced Western nations has focused primarily on the body and the mind of the patient. While this emphasis is, without doubt, the most appropriate prism through which the impact of this devastating diagnosis can be examined, cultures that are rooted in social structures where the role of the extended family is still very strong, might need to be understood by looking at the impact of the disease not only on the patient but on the family as well.

In our study, close to half of the patients (43%) had difficulty in meeting the financial demands imposed by the treatment. They had to sell their properties, mortgage their properties or gold ornaments, or take personal loans at punitive interest rates for raising the money needed for the treatment. In the Irish setting which is a mixed public-private healthcare system, the financial adjustment was done by using savings, borrowing and cutting back on the household expenses.[19] As India has not developed a universal health scheme to support cancer care, the family that is an extension of the patient, steps in to bear the burden during this vulnerable time.

About half of the patients, and by extension, their families had difficulty in managing their finances and as a consequence had a stressful situation. This stress affected their emotional well-being. According to Fenn et al. who used data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey, of 2108 adult cancer patients, those who reported cancer-related financial stress and strain were more likely to rate their mental health and satisfaction with social activities as poor.[20] In a study conducted by Shape et al., in Ireland, using a group of 654 cancer patients, they found that the risk of depression was raised threefold in those who reported increased cancer-related financial stress and strain.[21]

The story of modern India that is present in the popular English language press as well as the imagination of educated Indians is one of increasing economic growth, urbanization, accompanied by a gradual loosening of the rigidly hierarchical, patriarchal familial structure. In addition to this, it is believed that higher education of women translates directly and immediately into emancipation both psychological as well as financial. Our results suggest that while we are clearly in a state of transition, the lasting effects of past social structures such as patriarchy are pervasive. Though just about a third of the women in our study made the treatment decision independently, even this figure is most likely to be an inflated measure, and not reflective of the reality across India. Bengaluru, the city in which the current study was conducted, was historically an English cantonment and is the hub of the information technology outsourcing industry in India.

A particularly worrisome finding in our study was the degree and pervasiveness of social embarrassment in the vast majority of our participants (90%). The fact that this feeling of embarrassment was seen in both young and old, rural and urban, and in those who had a college education suggests that women have deep seated issues about their physical appearances as well as what they perceive as socially acceptable alterations in their appearance and functioning. Regardless of what approaches and policies are used to improve clinical outcomes in the management of breast cancer, unless we take serious note of this problem, and build appropriate strategies to help our patients, the improvement in the cure rates of breast cancer will not be accompanied by a commensurate improvement in the way the women feel about themselves.

The social theory maintains that in most traditional societies most members, and in particular women, are indoctrinated from early life to define themselves in terms of the social and familial roles they fulfill rather than as independent sentient beings. This aspect was clearly visible in the descriptions of the major concerns of the patients. Based on their age and the age of their children and parents, they saw themselves mostly as supporters and providers.

An encouraging aspect of the results of our study was the fact that post breast cancer, women started taking better care of their health and themselves. While it seems too heavy a price to pay for greater concern about oneself, it is still reassuring to know that life-altering experiences can lead to changes in deeply entrenched behavior patterns.

Strengths and limitations of study

The striking strength of this study is the significant sample size of close to 380 women, length of follow-up with almost no attrition except that caused by death. This long contact permitted repeated interaction that allowed an intimacy that is not possible in limited interactions.

The psycho-social support during the course of this 9-year study was provided by a single person (AA) throughout. While this is undoubtedly an extraordinary accomplishment, it does raise the possibility of a systematic bias emanating from the personality of the counselor. Additional research is needed to examine if these results would be replicated with other counselors in a rigorous trial. Over the duration of the study close to a third of the patients expired. The information of these particular patients might not be as detailed or accurate when compared to the long-term survivors.

This study was conducted in two charitable hospitals in a metropolitan setting. Our patients were mostly from the middle and lower-middle classes with a small proportion of the upper middle class. Clearly this is not reflective of the pan-India situation where the rural uneducated population make-up a full two thirds.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Diagnosis of breast cancer poses a significant financial and psychosocial burden not only on patients, but also on the immediate family members. Family plays a vital role in the lives of breast cancer patients through managing their finance, decision making, providing emotional support and remaining involved throughout the course of the disease. Involving the family in planned psycho-social interventions might produce better results than merely patient focused strategies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nadathur Holdings, Bengaluru and Bagaria Education Trust, Bengaluru, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Nadathur Holdings, Bengaluru, and Bagaria Education Trust, Bengaluru, India. We thank Ms Anamma Thomas and Dr Manjulika Vaz for helping structure the manuscript, and Prof. Maria Ekstrand, UCSF, for her feedback and critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Epidemiology of breast cancer in Indian women. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:289-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2012. Global Comparison: Statistics of Breast Cancer in India Website. Available from: http://www.breastcancerindia.net/statistics/stat_global.html

- Situating elderly role in family decision-making: Indian scenario. Indian J Gerontol. 2017;31:43-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Communication in cancer care: Psycho-social, interactional, and cultural issues. A general overview and the example of India. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1332.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient-reported quality of life outcomes in Indian breast cancer patients: Importance, review of the researches, determinants and future directions. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:11-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psycho-oncology research in India: Current status and future directions. J Indain Acad Appl Psychol. 2008;34:7-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Volunteering to take on power: Experimental evidence from matrilineal and patriarchal societies in India. In: Normann PD, ed. Volunteering to Take on Power: Experimental Evidence from Matrilineal and Patriarchal Societies in India. Germany: Düsseldorf University Press; 2015. Available from: http://www.dic.hhu.de

- [Google Scholar]

- Women empowerment: Status and challenges (A Study of Haryana State) Int J Adv Res Dev. 2017;2:329-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Living with gynecologic cancer: Experience of women and their partners. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40:241-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of culture and sociological and psychological issues on muslim patients with breast cancer in Pakistan. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:317-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Body image and sexuality in women survivors of breast cancer in India: Qualitative findings. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:13-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of radiotherapy on psychological, financial, and sexual aspects in postmastectomy carcinoma breast patients: A prospective study and management. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017;4:69-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosexual problems of cancer patients and their spouses results of an open ended survey. 2012. World J Psychol Soc Oncol. 4:1. Available from: http://npplweb.com/wjpso/fulltext/1/1

- [Google Scholar]

- Psycho-oncology: Indian experiences. In: Mehrotra S, Chakrabarti S, eds. Development of Psychiatry in India. India: Springer; 2015. p. :2-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- : Establishing the Validity of Qualitative Studies. 2002. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/file.PostFileLoader.html?id=52c3ea2dd039b19a718b47c0andassetKey=AS:273576857407491@1442237213988

- [Google Scholar]

- Triangulation in social research: Qualitative and quantitative methods can really be mixed. In: Holborn M, ed. Developments in Sociology: An Annual Review. Ormskirk, Lancs, UK: Causeway Press; 2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- “It's at a time in your life when you are most vulnerable”: A qualitative exploration of the financial impact of a cancer diagnosis and implications for financial protection in health. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77549.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:745-55.

- [Google Scholar]