Translate this page into:

The Process of Pain Management in Cancer Patients at Home: Causing the Least Harm – A Grounded Theory Study

Address for correspondence: Marzieh Khatooni, Nursing Care Research Centre, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. E-mail: khatoni.m@iums.ac.ir

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Cancer pain management at home is a complicated and multidimensional experience that affects the foundational aspects of patients and their families' lives. Understanding the pain relief process and the outcomes of palliative care at home is essential for designing programs to improve the quality of life of patients and their families.

Objective:

To explore family caregivers and patients' experiences of pain management at home and develop a substantive theory.

Design:

The study was carried out using a grounded theory methodology.

Setting/Participants:

Twenty patients and 32 family caregivers were recruited from Oncology wards and palliative medicine clinics in the hospitals affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences using Purposeful and theoretical sampling.

Results:

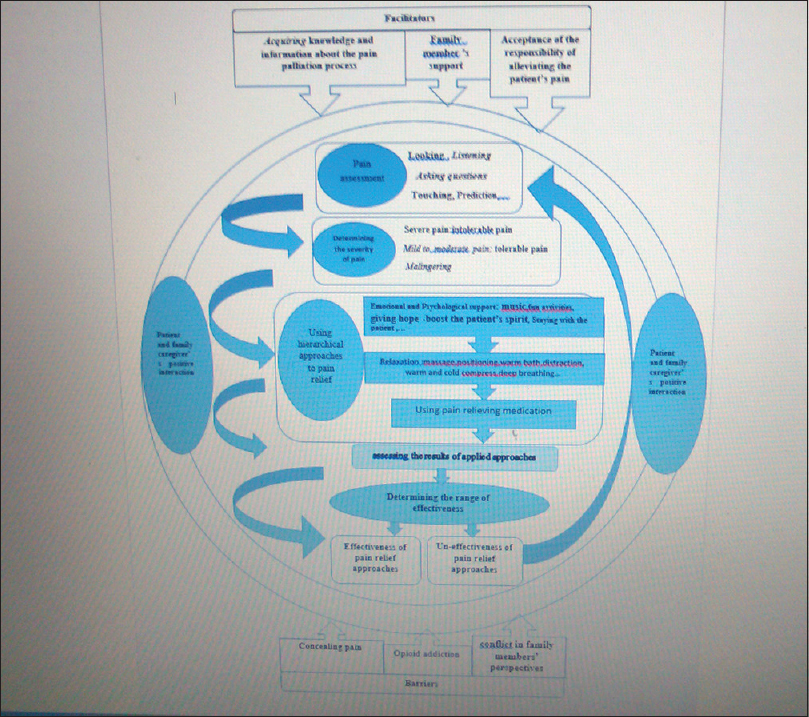

The core category in this study was “pain relief with the least harm.” Other categories were formed around the core category including “pain assessment, determining the severity of pain, using hierarchical approaches to pain relief, assessing the results of applied approaches, determining the range of effectiveness, and barriers and facilitators of pain relief.” The substantive theory emerged from these categories was “Pain management process in cancer patients at home: Causing the least harm” that explains the stages of applying hierarchical approaches to pain relief, family care givers try to make decisions in a way that maximize pain relief and minimize damage to the patient. Along with using a hierarchical pattern, the process is featured with a circular pattern at broader perspective, which reflects dynamism of the process.

Conclusion:

The inferred categories and theory can expand knowledge and awareness about the stages of pain relief process, the pattern of using pain relief approaches, and the barriers and facilitators of pain relief process at home. Health-care professionals may use these findings to assess the knowledge, skill, capability, problems, and needs of family caregivers and patients and develop supportive and educational programs to improve the efficiency of pain relief process at home and improve the patients' quality of life.

Keywords

Cancer pain

family caregiver

grounded theory

home care

pain management

palliative care

INTRODUCTION

Pain is the most common and important symptoms of cancer progress and also the main stressor for patients and their families.[12345] Etiology of cancer pain is multifactorial and it results from tissue damage or the side effects of cancer treatments such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgery.[678] Metastasis and involvement of other parts of the body bring different kinds of pain to the patient, and depending on the progress level of the disease and treatments, there is a need for modifications in pain relief approaches.[19]

In most cases, the severity of cancer pain ranges from moderate to severe[3] and it is estimated that 70%–80% of patients with advanced cancer suffer severe pains.[10] In general, 50%–70% of cancer patients experience different levels of pain, while only one half of them receive adequate palliative treatments.[2811]

As the disease progresses and when the treatments become ineffective, pain alleviation becomes the main objective. In fact, in the late stages of the disease, pain alleviation becomes the main focus of the cares provided to the patient.[412] From the patients and family care givers' viewpoints, pain management is more than a mere pain monitoring and following therapeutic and palliative instructions so that it encompasses the foundations of lives of these patients and their care givers.[13] In fact, pain assessment and management are of the biggest challenges for cancer patients and their families.[9]

Unrelieved pain in cancer patients leads to disruption of their comfort, capabilities, motivations, interactions with family members and friends, and the quality of life.[9] These in turn lead to depression, anxiety, frustration, sexual performance problems, and limitation in daily activities. Not-controlled pains are of the factors that even lead patients toward committing suicide.[7] Thereby, these patients need their families' full support.[4] In fact, the main portion of the care provided to patients with advanced cancer happens at home. As a consequence of health-care cost-containment strategies, hospital care has shifted to the home environment and family care givers as the first line of care providers for patients with advanced cancer in long-term are considered.[31415] In this regard, family is the main source of providing care to cancer patients.[12161718] On the other hand, many patients, especially those at the end stages of their disease, prefer to receive end-of-life care in their own homes and being cared for by their families.[1920]

Desire and ability of family members to provide care for these patients are the main factors in the success of pain alleviation.[1619] The patient and family's attitudes and beliefs about pain are effective in the pain relief process.[1317] Misconceptions such as pain is an inevitable part of cancer and there is nothing to do about it, or intensification of pain means that the patient is near death, hinder an effective pain management. In some cases, families with this viewpoint even do not ask for help from the medical team.[13] Ineffective interventions and failure of pain management approaches at advanced level of disease in particular are major challenges for family care givers. Some of these families do not have the knowledge and cannot achieve an agreement about the types of pain and the best way of controlling pain. Consequently, many of these families and their patients do not find themselves ready and equipped enough to handle this long-term crisis and meet the patient's needs, which in turn leads to inadequate pain management.[132122]

Improvement of the quality of life of cancer patients using appropriate and timely palliative care is a necessity,[3] so that one of the first objectives of the treatment plans for these patients is to alleviate pain.[23] Given the fact that the family members bear the main responsibility for pain management of these patients[521] and that they are the main providers of informal cares during the final stages of lives of these patients,[2124] it is important for health-care professionals to understand the pain management approaches used by the patients and caregivers and their needs and challenges. Subsequently, they can develop effective programs to improve the quality of life for patients and their families.[122124] In light of this, the present grounded theory study aims to explore and describe patients' and caregivers' roles and experiences in pain management, successful and unsuccessful strategies in pain relief, the effective factors, and pain management methods from dyadic perspectives of family care givers and patients.

METHODS

Design

The study was conducted using a grounded theory approach, which is a method to describe behavioral patterns and lived experiences of individuals and to develop theories about the main issues in peoples' lives.[25] The majority of grounded theory studies try to explore social experiences and psychosocial and stepwise stages that define a specific phenomenon or event.[2627] Grounded theory method is based on symbolic interactionism and allows individuals to discover and perceive meanings through interacting with others.[2829] It also allows researchers to find new aspects of phenomena. Therefore, this method can yield a theory based on actual events and in a systematic way.[30] This approach uses flexible methods for data gathering, analyzing, and extracting meaning from data and upgrading codes from a conceptual level to a formulated theory level.[31] The emerged theory is substantive as it elaborates on the experience from a particular population or setting's viewpoint.[32] The constituents of grounded theory method are theoretical sampling, constant comparative data analysis, theoretical sampling, memoing, determining the core category, and developing a explorative theory.[30] The methodology used in this study was grounded theory based on Strauss and Corbin's (2015) approach to explore the deep experiences of patients and family caregivers in pain management at home and develop a substantive theory.

Setting and participants

The setting of this study was oncology wards and palliative medicine clinics in the hospitals affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences. The study population consisted of all adult cancer patients (older than 18 years old) who suffered from pain and their family caregivers. Inclusion criteria for the patients were having cancer disease; suffering from pain; ability to ponder, rethink, and express experiences; living at home; and desire to participate in the study. In addition, inclusion criteria for the family caregivers were having the main responsibility of providing care at home; ability to ponder, rethink, and express deep experiences; and desire to participate in the study. The number of participants was determined based on the collected data and theoretical completeness. Sampling was done through purposeful sampling, and then as the data collection progressed, theoretical sampling was used; data gathering was continued until data redundancy. Participants were 32 family caregivers at the age range of 24–72 years and 20 patients at the age range of 18–79 years [Table 1].

| Characteristics | Patients (n=20) | Family caregivers (n=32) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean age (range), years | 42 (18-79) | 47 (24-72) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | 23 |

| Female | 8 | 9 |

| Education | ||

| No formal education | 1 | 1 |

| Elementary | 4 | 5 |

| High school | 6 | 12 |

| University/college/technical school | 5 | 9 |

| Postgraduate university | 4 | 5 |

| Relationship of family caregiver to the patient | ||

| Mother | 9 | |

| Father | 2 | |

| Wife | 9 | |

| Husband | 3 | |

| Daughter | 5 | |

| Son | 3 | |

| Brother | 1 | |

| Mean length of caregiving experience (range) | 2.2 years (6 month-4 years) | |

| Type of cancer | ||

| Breast | 2 | |

| Lung | 1 | |

| Colon | 3 | |

| Leukaemia | 5 | |

| Brain tomor | 1 | |

| Pancreatic | 1 | |

| Prostate | 2 | |

| Ovarian | 1 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 | |

| Sarcoma | 1 | |

| Bone | 1 | |

| Employment status | ||

| On sick leave | 2 | |

| Disable to work | 4 | |

| Retired | 4 | 4 |

| Working full-time | 3 | |

| Working part-time | 6 | |

| Homemaker (disable) | 5 | 15 |

| University and high school student | 4 | 4 |

Data collection

The patients and caregivers were interviewed separately. Data were collected via in-depth unstructured interviews. The face-to-face interviews with patients would be started by an open-ended question, “tell us about your experiences since you have been cared for at home.” In interviews with care givers, the open-ended question was “tell us about your experience since your patient is under your care at home.” Based on the respondents' answers, the interviews would be continued by probing questions. The interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min in the case of patients and between 60 and 100 min in the case of caregivers. With permission of the participants, the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim afterward.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences under the code IR.IUMS.2018.780. Other ethical concerns were stating the objectives of the study for the participants, securing an informed consent, signing written informed letter of consent by the participants for an informed and voluntarily participation, observing unanimity and confidentiality of the information, asking permission of the participants to audio-record the interviews, and reminding the participants of their right to leave the study at whatever stage.

Data analysis

Constant comparative data analysis was conducted along with data gathering based on Strauss and Corbin's (2015) guideline at five stages. These stages are data analyzing and identifying the concepts for open coding; constant comparative analyses based on the differences and similarities and describing the aspects and details of the concepts (axial coding); analyzing information to prepare the ground; adding the process to the analysis; and integrating categories where categories are connected to the core category and theory are modified and finalized.[29]

RESULTS

A substantive theory “Pain management process in cancer patients at home: Causing the least harm” was emerged from the data that explains the experiences of patients and family caregivers about the process of pain management at home, the adopted strategies to pain relief, and the effective factors in the process. The main objective followed by the participants in each step of pain relief was to prevent causing more harms and providing maximum pain relief and comfort for the patients. What led the participants to this objective was facing the short/long-term side effects of the medicines such as sedation, sleepiness, drowsiness, slowed breathing, clouded thinking, constipation, and addiction. Some of the participants mentioned the problems of inadequate alleviation of pain such as weakness, severe lack of energy, sleep and eating disorders, disruption of patient's comfort, depression, anxiety, and even suicidal thoughts. Family caregiver No. 4, a mother, said:

”He was restless and could not sleep without the narcotics; and he was drowsy when he used the narcotics so that he would not understand what we were saying to him. My boy was always asleep,…, and sometimes with severe constipation, which led to hemorrhoids,…, and frequent bleedings and burning so that he would cry when defecating. Once he only suffered from bone pain but then a new pain was added to his pains, which was more troubling than the old one.”

Therefore, the caregivers tried to adopt more accurate methods to evaluate and measure the severity of pain, find more efficient ways of alleviating pain, and cause the least harm to the patient. What was observed throughout the process was following the pain alleviation process step by step and using hierarchical pain relief approaches depending on the severity of pain. These step-by-step stages and the effective factors were categorized into eight major categories and several subcategories all around the main axis of the emerged theory. The main categories were “patient and family care giver interaction, pain assessment, determining severity of pain, using hierarchical approaches to pain relief, assessing the effectiveness of pain relief approaches, determining the effectiveness range of the approaches, barriers and facilitators of pain relief” [Figure 1]. These categories were described and clarified using the direct quotes from the participants (Family care giver (FCC), patient [P]).

- Cancer pain management at home: Causing the least harm

Patient and family caregiver's positive interaction

Proper relationship and interaction between patient and caregiver facilitated communicating pain and obtaining information about the pain. In general, when the major categories and pain management stages were completely clarified, we found that the interaction between family caregiver and patient was a background for other stages in the process so that it formed the context where pain management takes place in. Accepting the responsibility of pain management by the family caregiver played the main role in creating the positive interaction. The majority of caregivers mentioned that they were concerned about their patient's pain and found it an incumbent upon themselves to alleviate the pain. In addition, emotional attachment between family caregiver and patient was one of the factors in creating a better interaction.

”My boy only talks to me about his pain. He is not Ok with talking to his father about this because their relationship is not that good. He goes through the pain but do not asks his father's help when I am not at home. His relationship with me is very good; after all I am his mother and were deeply attached” (FCG 2, mother).

In addition, the patients noted that they preferred a specific family member to be in charge of providing care to them and refeered to specific member of their family as reliable person to share and alleviate their pain, a person who gave hope and peace to them. “I really love my wife. Although, we are married for only 4 years and we have a small kid, she would do anything she could to help me. It is only with her that I feel in peace. She understands my pain and knows what to do” (P3, male).

There was only one case where lack of a proper FCG-P relationship led to negligence of the patient and suboptimal pain control for the patient: “My wife has left a few years ago. My children are at work during the day and they don't pay attention to me when they are at home. What they do is to give me food and my medicine and then spend their time at their room. They don't ask how do I feel? Most of the time I have pain but I wouldn't tell them” (P. Male).

Positive FCG-P relationship and interaction is the main element of a successful palliative care, and without it, pain assessment and relief fail to achieve the expected results.

Pain assessment

This major category has the following four subcategories: (1) listening and (2) asking questions and (3) looking and (4) paying attention to physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms and prediction.

Listening and asking questions

One of the ways of creating an effective FCG-P relationship is to have a clear understanding of the nature and severity of pain through listening and asking questions. Listening to what the patient has to say and their description of pain is the first and foremost way of pain assessment. In many cases, patients were able to express and describe their pain and share their pain verbally and clearly. They described pains as burning, friction, compressive, stabbing and sharp, tenesmus, cramp, and feeling burst at different areas like abdomen. They were also able to determine the area of pain, its frequency, oscillation, peaks, and what intensified the pain (e.g., movement, eating, and changing positions). “My mom cannot bear the pain anymore; she calls me the moment the pain starts. She says “my bones are aching like they pressing something pointy into my bones” then asked me to press her bones” (FCG 6, son).

”When I am in pain, I ask my wife for help. I would say it is my stomach… whenever it starts, I feel like my stomach is going to burst” (p 11, male).

Indirect expression of pain was mostly by the patients who were not able to express their feeling verbally or entered into emotional moods and expressed their pain along with other psychological and behavioral signs such as moaning, screaming, crying, murmuring, decreased tone of voice, or moaning at sleep. In addition, patients with a decrease in consciousness level or cognitive disorders were not able to express their pain in a clear way. They would express the pain by making voices lie “ah” or “aakh” or sudden and short shouts. Patients' inability to describe their pain hindered pain assessment process (area and severity of pain) for the caregivers. “He is not able to talk since his disease has progressed. The only sound he makes is moaning or 'aak'. Sometimes I bend and close my ear to his mouth to hear better so that I might understand what he says” (FCG 17, daughter).

After listening to what their patient has to say, family caregivers would try to find more information by asking questions about the specifications of the pain. They would also reflect their understanding about the severity, place, and other specifications of pain to the patient and ask the patient to confirm the assessment. When the patient demonstrates the psychological and behavioral symptom, the care givers ask questions about the symptoms of pain to distinguish them from those of sadness and make sure that such behaviors and psychological symptoms are not merely due to depression and sadness. In some cases, the family care givers believed that the patient was trying to hide their pain and had to ask questions. “When I see him frowned, stared at one spot, and silent, I know that he is in pain. He would not complain so that I have to ask him if he is in pain? Only then he admits a bit of pain, but I know that how severe is that bit of pain” (FCG 20, brother).

Looking and paying attention to physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms

Paying attention to the visual pain indicators is one of the most reliable ways of pain assessment by caregivers. These symptoms help the family caregivers to determine the area and severity of pain. Sometimes, it was hard for the family caregivers to trust the patient's statements about the severity of pain and other specifications. This is mostly true for the case with old patients or patients with cognitive disorder, disorders of consciousness, patients with verbal disabilities, patients who hide their pain, or patients who have developed addiction to medicines. The caregivers noted that paying attention and watching physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms along with listening to patients' expression of pain added to their confidence of their pain assessment. The most common physical symptoms' expression of pain observed by the caregivers was sleep disorder (waking up frequently mostly overnight), sweating, pale face, flushing in some cases, change in facial expression and frowning, feeling nausea, lack of appetite, increased breathing rate, lack of energy, feeling pain after movement and feeling pain in legs, and inflamed legs. In addition, skin redness, blisters, skin inflammation after radiotherapy, pain in the surgery area, aphthous ulcer, and glossitis following chemotherapy were clear symptoms of pain.” when she is in pain her face color looks like white plaster and and her lips would be dry. She frowns, cannot sleep overnight, and keep moaning when she is pain…. She would say 'I'm burning'” (FCG 29, husband).

”By now it has been 2 months that my mother suffers severe bone pain. She keeps asking me to massage her back. She cannot stay in one position. She cannot sit… and screams in pain overnight” (FCG 18, daughter).

Most of the time, severe and persistent pain was accompanied by psychological and behavioral symptoms. These symptoms include agitated behavior, aggressive motions, punching, and knocking the head or limbs around or a decrease in activity and staying at bed. Other behaviors such as writhing, pressing the painful area and covering it with hand, changing body position frequently between sitting and supine positions, anger and temper, sadness, and speaking less than the usual during the pain, were effective in assessing the pain and determining the severity of pain. Some of the caregivers noted that some of the psychological and behavioral symptoms were observed constantly in patients with chronic pain, but in particular, when pain started or intensified, these symptoms were also exacerbated. “He cries and shouts when the pain increases; sometimes he bites the pillow and waves his fist in front of his stomach. He cries 'God please finish it'” (FCG 11, wife).

”She folds her legs into her stomach and keeps the pressed on her stomach. She bites her lips and her face sweats. She closes her eyes and cries and moans. If we ask her something she shouts 'shut up'” (FCG 17, husband).

Touching

Touching the painful area causes more pain and most of the caregivers avoided doing so. They mentioned that sometimes accidentally and unintentionally touched the painful area and the patients react with screaming or pulling back. Such responses confirm the pain:” When I want to change her position in the bed or massage her, she would say 'be gentle please and do not touch my legs. They hurt.' Her legs are swollen and very painful. She never lets me to touch them.” (FCG 27, daughter).

Prediction

Patients and care givers with a long experience with the disease and caring were able to predict the condition and factors that caused more pain. They were able to predict initiation of pain after therapeutic procedures, intensification of the pain as the disease progresses, and initiation of pain after pain causing stimulators such as moving the body or eating. By prediction, there would be no need to confirm and check the pain: “I know that chemotherapy causes aphthous and burn. Therefore, when he says that his mouth burns and he cannot eat, I am sure that he is in pain and I try to help him by preparing soft and watery foods” (FCG 23, mother).

Determining the severity of pain

Determining the exact severity of pain was an important and essential step in making the right decision about the pain relief approach and the right time to use them. This major category consisted of three subcategories of severe pain (intolerable pain), mild-to-moderate pain (tolerable pain), and malingering.

Severe or intolerable pain

Determining severe and intolerable pain was mainly based on the patient's expression and descriptions of the severity of pain such as killing pain, agonizing, and intolerable. Then, the family care givers confirm the severity of pain based on the physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms. Family care givers found symptoms such as waking up and starting to cry or moan, fainting due to the severity of pain, sudden sweat and pale face, bad temper, and screaming with no reason as the symptoms to confirm a severe pain. The care givers with longer experience in taking care of their patients found a set of specific symptoms as the symptoms of severe and intolerable pain.” When he is in a severe pain, his face becomes pale and sweaty … then he writhes and screams” (FCG 25, Son).

In some cases where the disease was highly progressed, the participants noted that using nonpharmaceutical palliative approach or even using the painkillers that used to be effective became ineffective and only using narcotic painkillers could help. The participants found such a situation as a symptom of severity of pain. “The painkiller pills were effective in the early days that they took out the tumor out of his brain. However, since the recurrence of the tumor, his pain has become even more severe and only narcotic pain killers can help him” (FCG 12, father).

Mild-to-moderate pain (tolerable pain)

In this cases also, the patient's expression about tolerability of the pain was the first measure. The patients were expressing that the pain is tolerable and they were reluctant to consume painkiller unless the pain becomes unbearable. Lack of physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms was another clue. In addition, family care givers find effectiveness of nonpharmacological approaches such as massaging, warming the painful area, or effectiveness of usual pain killers such as acetaminophen as the clues of mild-to-moderate pains.” When the pain is not severe, I would ask my mom to massage my legs and back with olive oil or help me to take a warm shower. In this way I feel better” (P15, son).

Malingering

In some cases, there was an inconsistency between the pain that expressed by the patient and how it was perceived by the caregiver. Indeed, verbal expression and psychobehavioral reactions of patients did not match the assessments and observations of family caregivers. Such noncongruent dyad in the perceived pain was reported by the caregivers as “pretending to have pain” and became known as “malingering.”

They noted that they knew their patients, and based on their approaches for verification of pain, they would conclude that in some cases the pain expressions are not based on real pain. These malingering behaviors are to seek attention, to receive more psychological and emotional support, or due to drug addiction and trying to get the most out of it.

”I know that my boy has become dependent on the drugs. To avoid the fact that he has cancer, he prefers to spend most of his time asleep. Therefore, he keeps complaining about pain and asks for more morphine” (FCG 4 mother). One of the main negative outcomes of malingering was the disruption of the mutual FCG-P relationship and fatigue in the caregivers, which resulted in disruption in the process of pain alleviation. “Six months after the treatment and despite the fact that physicians believe that the treatment was highly successful, she still says that she is pain. She cries and begs for narcotic sedative. If I refuse, she will scream and become aggressive. This drives me mad. She would throw anything she can towards me. I have talked to her doctor; he believes that she is addicted” (FCG 7 mother).

Hierarchical approaches to pain relief

In most of the cases, utilization of pain relief approaches has hierarchical pattern, so that after diagnosing the pain and its severity, caregivers use a hierarchical approach that starts with nonpharmacological palliative solutions and drugs are used if these solutions fail to relieve the pain. The participants stated that using medicines is not the only solution to relieve pain. Family caregivers and patients knew that pharmacological approaches were faster and more efficient ways to relieve pain; however, they preferred not to start with those approaches given the risk of addiction, development of drug resistance, the side effects, and the multiple drugs that might be used by the patient. On the other hand, some of the family caregivers believed that inadequate alleviation of pain has destructive effects and leads to more physical weaknesses and psychological problems. Therefore, they tried to avoid more serious harm to the patient and at the same time maximize palliation by choosing the best and most effective approach. This category plays a key role in the development of home pain management process theory: “causing least harm” with three subcategories including emotional–psychological supports, relaxing solutions, and using pain-relieving medication.

Emotional–psychological supports

Solutions to boost the patient's mood and spirit or distracting attention from pain were used when the pain was assessed as mild and tolerable or the family caregivers are convinced that their patient pretending to have pain or the patient is anxious, scared, depressed, or hopeless. Energetic activities such as listening to music, having fun, taking the patient outside, giving hope to the patient, gathering around children and those the patient enjoys their company, watching movies, light physical exercises, and praying and reading the holy books are some of the solutions that the patients found palliative. Sometimes, the caregivers tried to induce strength to cope with the pain, not to notice it, or being strong in the face of pain:” When my boy says 'Mom I have a little pain' or find him a bit sad and down, I try to distract his attention. We would play a game or watch a comic movie or listen to a happy music. In this way, he will be distracted for a few hours” (FCG5, mother).

”When I am in pain, my wife would play a happy music and my daughter dance for me. Then I forget all about the pain” (P18, male).

Staying with the patient throughout the time that the patient was in pain not only attenuated their anxiety but also enabled the caregiver to find about the patient's pain early enough to take an approach. The family care givers stated that they tried to conceal the sorrow and concern to keep the spirit of their patient high. In addition, in the face of occasional aggressive behavior of patients, they try to stay calm and calm the patient by talking to them: “He is very aggressive when he is in pain; but I understand. I would sit next to him and pet him and try to distract him from the pain. I would tell him that he is going to be Ok and that he must be strong. In this way I try to make him calm” (FCG 28, wife). “When I am in pain, my daughter would sit next to me and pray and read the Holy Quran. In this way I feel calm and the pain is alleviated” (P17, male).

Relaxing solutions

A practical approach to pain relief is to massage the painful areas by different oils such as olive oil, using warm compress, taking warm bath, placing the patient in special positions (e.g., keeping the swollen legs above the body, or keep changing position in the case of bone pain), and creating a quiet and peaceful environment. Some of the patients and caregivers stated that spiritual approaches such as praying and reading the Holy Quran were effective in alleviating the pain and making it more tolerable. “I would massage her legs and back with olive oil or take her to the bath for a warm shower when he is in pain. After the shower, he says that the pain is much less and that he feels better…. Then he can take a peaceful nap for a few hours” ( FCG 15, mother).

Using pain-relieving medication

If the above approaches were not effective and the pain persists, the family care givers would use pharmacological pain relief. Nonnarcotic medicines like prescribed pills and lotions were the first choices. Using these medicines depends on the severity of pain and the patient's response to painkillers. Using narcotic painkillers was the last choice for the family caregiver. The participants were aware of the side effects of the narcotic pain killers and expressed their concerns in this regard. “Trying to bear the pain as much as possible” was a concept that mentioned by most of the patients. Still, in some cases, narcotic painkillers were used as the last resort. However, in some cases that the disease was quite advanced and the participants knew by experience that nonpharmaceutical solutions were ineffective, the hierarchical approach would not be an option. In these cases, the prescribed narcotic painkillers would be used at the first choice. In addition, the family caregivers stated that they kept using psychological supports and other approaches such as relaxing patient with massage in the entire duration of the patient's pain.

Assessment of the outcomes of pain relief approaches

Assessment of the outcomes would be done continuously throughout the pain management process by the participants using the same approaches used in the early stage of assessing the severity of pain.

Determining the range of effectiveness

The range of effectiveness reported from complete pain relief to nonalleviation. Among the clues of pain alleviation were the patient's expression as to alleviation of the pain, better sleep quality, good appetite, increase in the ability to do physical activities, better mood, and positive facial expressions. On the other hand, the clues of failure of pain relief approaches in the patient were writhing, sweating, sleep disorder, and continuous moaning. When the pain was not relieved, the participants would reassess the pain in a more accurate way, adopt other approaches, move to the next step of pain alleviation, use higher dosage of painkiller or use the painkiller with shorter time gaps, and look for the causes of ineffectiveness of the palliative approaches. Returning to the early steps of pain assessment and the following pain relief steps indicate the cyclic and dynamic nature of pain palliation process. In the case of the failure of pain palliative measures at home, mostly at advanced stages of the disease, taking the patient to hospital was the last measure. “Even though I give her morphine every two to three hours at home, her pain doesn't go away and she is constantly in pain. The pain was so severe that she had became badly weak. She was in an anxious mood and thought that she was going to die. She keeps saying I'm dying. Don't let me die. She was begging us to save her, so we took her to the hospital….” (FCG 12, husband).

Barriers to pain relief

Opioid addiction, concealing pain, and conflict in family members' perspectives about using pain relief approaches were mentioned as three main barriers in pain relief.

Opioid drug dependence and asking for more narcotic painkillers particularly by young patients was one of the causes of ambiguity for the family caregivers to recognize the real pain of malingering.” We are always arguing about the narcotic substances. I cannot tell when he is really in pain anymore. All I know that in most of the cases he is faking. Sometimes I leave him at home for hours to calm my nerve. The thought that my boy is now a drug addict is as painful as the moment I found that he has blood cancer” (FCG11, mother).

Concealing pain was one the main barriers to assess pain accurately. The main reason for hiding and enduring pain was to avoid worrying and bothering the caregivers or causing trouble for them. “My mother is very patient and laconic. Although, she is always in pain, she never complains. She does not want to worry us… Still I can tell by her face when she is in pain. Sometimes it is hard to tell” (FCG 6, daughter).

”I try to stay calm as much as I can and do not complain. I cover my face with the blanket when the pain is too hard so that other would not see my crying. I don't want to agonize my children anymore you know” (P18, female).

Conflict in family members' perspectives about pain palliation measures was a source of quarrels in families and an obstacle of pain relief. Patients' relatives' unawareness about pain management process and irrational interventions such as using medicine in an improper way or using handmade traditional painkillers that usually lead to side effects and more trouble for the patient were some of the issues. “While I am highly worried about drug addiction in my son, his sister and father cannot understand my concerns. The only thing that matters for them is the pain. They insist that I should administer the painkiller the moment he starts to complain about the pain. They really bother me and there is always a quarrel among us” (FCG 17, mother).

Another aspect of the conflict was the belief in some of the family members that feeling pain is natural. These individuals were inconsiderate about their patient's pains and this was a cause of tension and disruption in the process of pain alleviation at home.

Facilitators of pain relief

Acquiring knowledge and information about the pain palliation process and having the family's support were among the main facilitators of pain palliation.

Learning about the nature of pain and how to relieve it using formal and informal resources such as health-care professionals, the Internet, and others who have experiences in this area like friends, relatives, and even other patients with similar disease resulted in a deeper perception of pain experience and a more reliable assessment of each steps in pain relief process. “Since I have been diagnosed with the disease, I have tried to learn about it and ways to treat it on the Internet. Now I even know more than my doctor (laughter). I now about the side-effects of painkillers and that the side-effects are much worse than the pain. Therefore, I try to endure the pain and use nondrug ways to reduce my pain” (P16, son).

In addition, the family members' support and their participation in the caring process facilitated dividing the task of care between family members and preventing fatigue and burnout in main caregivers of the family. “My daughter comes in the afternoon. She is married. When she is here and looks after her mother, I can take a nap and rest. In this way I can stay up until the morning and look after my wife.” (FCG 22. Husband).

DISCUSSION

The experiences of cancer patients and family care givers about pain management process at home were explored and described using a grounded theory approach. The dyadic perspectives of the family caregivers and patients were obtained simultaneously. Pain management process is happening in the context of mutual and dynamic interaction between the patient and family caregiver. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to their dyadic and unique perspectives rather than emphasizing on their experiences in isolation. This approach leads to trust and belief in the interactive care process and different roles and responsibilities of patients and family caregivers.

This study developed the substantive theory of pain management process in cancer patients at home: causing the least harm. The theory explains that the experience of encountering the different adverse side effects of medicines resulted in serious health problems and/or failure to use the pain relief approaches in an efficient way. This compelled the patients and family caregivers to made different decisions and took different measures in a way to avoid physical and psychological damages to the patient and maximize of pain relief. The theory also revealed that the process is featured with dynamic, step-by-step, and hierarchical specifications and a cyclic nature in a broader sense. There are several factors in the process that act either as facilitators or barriers.

The results showed that progressing in this process was merely based on personal experience, knowledge, and capability of the participants and there was no formal education, social support, and formal intervention of the medical team in alleviation of pain at home.

Positive interaction between the patient and family caregivers was the first and basic condition of caring. Acceptance of the responsibility of alleviating the patient's pain by the family caregivers resulted in a dynamic and deep interaction between the two parties with respect and empathy, which in turn led to proper communication of pain and shared decision making. The majority of family caregivers had a strong emotional relationship with their patient and believed that relieving their patient's pain was their main responsibility, so that they would leave their normal lives and dedicate themselves to take care of their patient and alleviate their pain. This finding is consistent with similar studies in this field.[17193334] Mehta maintained that accepting the responsibility of palliative care by the family care givers was the first and most important piece of the puzzle of pain management at home.[19] In addition, McPherson argued that the first subtheme of the major theme sharing pain was to accept the roles in pain assessment.[13] This means that accepting duty and responsibility to pain management was the first and main step and a prerequisite of creating a proper ground for communication of pain and shared decision making. Here, the patients described their caregivers as trustworthy, empathic, and supportive so that they could trust in their care givers at any situation and share their pain with them.

The findings of the present study are consistent with other studies in showing that the first step of encountering pain is to assess it to determine the severity.[131419] Using a set of approaches of pain assessment to determine the severity of the pain was a comprehensive approach to assess the severity of pain. Taking into account the patient's expression about the type and severity of pain, having a verbal communication to share the pain, and asking questions to confirm the diagnosis constituted the first, best, and most important step to assess pain.[131935] In addition, paying attention to psychological symptoms and nonverbal behaviors was a major guide to determine the severity of pain. This method is used in specific cases that the patient tries to hide the pain, the patient is not able to speak, consciousness level is low, and there are sensory and cognitive disorders.[131936] However, some of the family caregivers relied more on their own instincts rather than the patient's expression of pain.[19]

In most cases, pain severity was mutually approved and agreed by the family caregivers and patients. That is, when the patient stated that the pain is tolerable or intolerable, the caregivers would find the patient's description consistent with their own assessment. However, malingering was a challenging issue so that it caused conflicts and disruption in patient–care giver relationship and pain management process. According to other studies in this area, the main reasons of malingering in patients with chronic pains were drug dependence and desire to receive more drug. Still, it is not easy to tell when a patient is malingering even in clinical settings at hospital as making the right judgment needs adequate evidences.[35]

A specific finding in this study was that utilization of pain relief approaches had a hierarchical pattern. Concerns about the side effects, drug dependence, drug resistance, and the beliefs that strong painkillers are only useful for severe pains[13373839] made the participants reluctant to use narcotic painkillers.[1404142] Therefore, safe and nonpharmacological approaches to relieve pain would be started by psychological and emotional supports, and in the next step, relaxation strategies would be applied. Since anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and uncertainty might intensify pain and suffering in cancer patients, psychological support and behavioral interventions can be highly effective in relieving patients' pain.[43] Therefore, psychological and relaxation approaches were the first choices by family caregivers and patients.[344344] They noted that these measures can be effective as some of pharmacological measures and lowered the patient's need for painkillers.[3943] If these approaches be found ineffective, the next step was nonnarcotic medicines prescribed by the physician. As the final approach, injectional narcotic medicines were used. Other studies have highlighted these approaches as well, however, in some cases.

Using medicine was the first approach to relieve pain and nonpharmacological methods are used as supplementary measures along with medicines or after using medicines. Some also have reported that mild-to-moderate pains are also dealt with by nonpharmaceutical approach as the first step.[9131939] Here, in the case of severe pains and patients at the final stages of the disease, hierarchical approach was replaced with using injectional narcotic painkillers and other approaches were used as supplementary method as long as the pain lasts. In such scenarios, the objective of family care givers was still to cause minimum harm to the patient, given that they found severe and nonalleviated paints, mainly at advance stages of disease, as debilitating factors that causing severe weakness and disability in the patient and decreases the their chance to survive. Other studies, however, have argued that the fear of medicinal side effects, wrong beliefs about painkillers, and insisting on not using narcotic painkillers were the main reasons for unreasonable pain suffering, failure to alleviate the pain, and the risk of facing serious health problems or early death.[204045]

Effectiveness range started from complete pain relief to relative relief and no relief of pain. However, the majority of caregivers made their best to alleviate the pain, while in some cases, the progressive nature of the disease was a barrier to achieve complete pain relief.[83646] In such cases, the participants expressed frustration and disability to manage the pain. Long-term and nonalleviated pains cause severe weakness, fear, and constant anxiety about intensification of pain in patients so that they might feel their death nearer than ever. These findings are supported by other studies.[579] Based on the preferences of the family and patient in particular, taking the patient to hospital and seeking medical help were the last resort.

The main barriers of pain management were drug addiction, concealing pain, and conflict in the family members' perspectives. Drug addiction was one of the barriers that added to the complicacy of pain management.[47] Patients with drug addiction might malinger to receive the opium[35] and they might demonstrate aggressive behaviors if their demand is not met. On the other hand, fulfilling their demands might intensify the dependence and result in the side effects. This was the main stressor for the family care givers and the parents of young patients in particular. The parents found the risk of drug addiction as worrying and bad as the cancer itself. Other studies have reported that frequent requests for painkillers by the patient would lead to medicinal side effects caused by overdose, as a barrier of pain alleviation.[3537] On the other hand, concealing pain to avoid causing concerns and fatigue in the family caregiver or causing excessive physical and psychological pressure on the caregivers was another barrier of pain assessment for family care givers. These findings are generally in line with previous studies.[203648] Some studies have reported that refusal to share pain experience was a way for the patient to keep their independence,[13] so that the patients were tended to tolerate the pain and not express it to reduce their dependence to caregivers.

Conflict in family members' perspectives appeared as disagreement about using pain relief approaches between the main caregiver and the other family member. Another factor for conflict was negligence of the other family members to caring and refusal of them to participation in pain management process. These factors led to tension and conflict among family members and disruption of pain management process. These findings align with other studies that reported family conflict in palliative care will hinder establishing shared goals of care and prevents proper pain management.[121745] In addition, stress, depression, and fatigue in the family caregivers were barriers that the main reason for it is reluctance of other family members to participant in care giving process.[202149] Undertaking parts of caregiving process by the family members and supporting the whole process of pain relief can lower the pressure on the main caregiver and facilitate the process of pain management. Another major facilitator was gaining the knowledge and information about pain relief process. The majority of previous studies have highlighted the lack of knowledge about the nature of cancer pain and its management approaches as a main barrier of pain management.[20373950] The participants in this study also had no formal education about pain management at home and their individual search on the Internet, asking questions from others, and using others experiences were the only sources of information for them. Attaining information is crucial to achieve a better perception of pain and develop pain management approaches.[19]

The present study shows similarities with Mcpherson and Mehta's theoretical framework. Mehta proposed the model of cancer pain management puzzle where pain relief stages at home are represented by puzzle pieces. These stages include accepting responsibility for pain management, establishing a pain management relationship, seeking information on pain management, implementing strategies for pain relief, determining characteristics of pain, and verifying the degree to which pain relief strategies are successful.[19] Therefore, Mehta's model is similar to the model presented in in this study in terms of pain relief stages. Also, two stages in Mcpherson's model including communicating the pain and finding a solution to pain relief are named as the main stages of pain management process so that communicating pain was based on an interactive and mutual process.[13] In this regard, our findings are consistent with their study.

What is clear in the present and other studies is that despite families strive to do their best to alleviate pain, some pains were not relieved at the end. This highlights the need for providing a wide range of educations about pain management process to the patients and their family members as well as extensive support by the health-care professionals to improve the quality of pain relief at home.[1319394950]

Limitations of the study

Reluctance or lack of ability of some of the patients to participate in interviews was a limitation that in some cases made it impossible to collected dyadic perspectives of the patient and care giver. This was mostly the case with the patients who had severe and long-term pains. To overcome this limitation, we tried to conduct interviews with the patient when the effectiveness of painkillers was the highest level and the patients' pain was relieved. In addition, the interviews with patients were conducted in several short sessions.

CONCLUSION

The emerged substantive theory “Pain management process in cancer patients at home: Causing the least harm” clearly explains the experiences, role, and attitude of participants about pain management process. The strengths of this study were to assessing the dyadic perspectives and experiences of the patients and care givers, diversity of samples, and the higher number of participants comparing with other studies. Therefore, the findings can be generalized to a wide range of individuals with cancer and the families in charge of palliative care for their patients. The emerged theory can be used as a framework for health-care professionals to assess knowledge, awareness, skill, and capability of family care givers with regard to each one of the stages of pain relief at home. They can also find the strengths and weaknesses of care givers performance as well as the barriers and facilitators of each stage. Using these deep insights, health-care professionals can develop caring, supportive, and educational programs to achieve the highest pain palliation and the least harm to patients as possible. Through this, patients' quality of life will improve and detrimental consequences for the family care givers can be minimized.

Financial support and sponsorship

This paper is a part of dissertation of a PhD graduated that supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (contract number: 97-4-3-13393).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to express their gratitude to all patients and family care givers who participated in this study and shared their valuable experiences.

REFERENCES

- Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: A qualitative longitudinal study. Palliat Med. 2016;30:711-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain experience among patients receiving cancer treatment: A Review Palliative Care. Medicine. 2013;3:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain coping behaviors of Saudi patients suffering from advanced cancer: A revisited experience. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(Suppl 1):103-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey of the degree of knowledge and experience of the cancer patient's family about pain control. Daneshvarmed. 2010;17:63-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of and barriers to pain management in caregivers of cancer patients receiving homecare. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:31-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breast cancer pain management-A review of current novel therapies. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:216-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of pain-related beliefs in adjustment to cancer pain. Daneshvar Raftar. 2005;12:1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain in cancer patients: Pain assessment by patients and family caregivers and problems experienced by caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1857-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Managing cancer pain: Frequently asked questions. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78:449-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informal hospice caregiver pain management concerns: A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2013;27:673-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- A qualitative investigation of the roles and perspectives of older patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers in managing pain in the home. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with the accuracy of family caregiver estimates of patient pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:31-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family caregivers' experiences and involvement with cancer pain management. J Palliat Care. 2004;20:287-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- The experience of family caregivers of patients with cancer in an Asian country: A grounded theory approach. Palliat Med. 2019;33:676-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer caregivers advocate a patient-and family-centered approach to advance care planning. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:1064-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family caregivers of palliative cancer patients at home: The puzzle of pain management. J Palliat Care. 2010;26:184-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceived barriers to symptoms management among family caregivers of cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:202-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences of family caregivers of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:5063-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer pain management among underserved minority outpatients. Cancer Nurs. 2002;94:2295-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick: Aldines Transaction; 1967.

- Qalitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. Wolter Kluwer: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011.

- The Discovery of Grounded Theory; strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Pub Co; 1967.

- The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Proces. New South Wales: Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest; 1998.

- Symbolic interactionism. In: Flicke U, von Kardoff E, Steinke I, eds. A Companion to Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc; 2004. p. :81-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed). California: SAGE Publications; 2015.

- Moving grounded theory into the 21st century: Part 2 – Mapping the footprints. Singapore Nurs J. 2006;33:12-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qual Health Res. 2006;16:547-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family experience caring forterminally ill patients with cancer in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:267-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-pharmacological Methods in Cancer Pain Control.Kanser ve Palyatif Bakımİmir. Meta Basım 2006:97-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain assessment tools for malingering in patients with chronic pain.Plus: Differentiating between this exaggeration and factitious disorder, somatization, and pain catastrophizing. Practical Pain Manag. 2019;19:23-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family caregivers' assessment of symptoms in patients with advanced cancer: Concordance with patients and factors affecting accuracy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:70-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer patient and caregiver experiences: Communication and pain management issues. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:566-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- What patients with cancer want to know about pain: A qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:177-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer pain: Knowledge and experiences from the perspective of the patient and their family caregivers. ARC J Nurs Healthc. 2017;3:6-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of patient-related barriers in cancer pain management in Turkish patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:727-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient-and family caregiver-related barriers to effective cancer pain control. Pain Management Nursin. 2015;16:10-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying attitudinal barriers to family management of cancer pain in palliative care in Taiwan. Palliat Med. 2000;14:463-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological and behavioral approaches to cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1703-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer patients' desire for psychological support: Prevalence and implications for screening patients'psychological needs. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;141:9-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Year Against Cancer Pain 2009

- Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain.A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1985-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of oncology patients' and their family caregivers' attitudes and concerns toward pain and pain management. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:328-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Feeling like a burden: Exploring the perspectives of patients at the end of life. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:417-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- You only have one chance to get it right: A qualitative study of relatives' experiences of caring at home for a family member with terminal cancer. Palliat Med. 2015;29:496-507.

- [Google Scholar]