Translate this page into:

‘We had to be there, Present to Help Him’: Local Evidence on the Feeling of Safety in End-of-Life Care in Togo

*Corresponding author: Mena Komi Agbodjavou, Multidisciplinary Doctoral School Spaces, Cultures and Development, Abomey Calavi University, Abomey Calavi, Benin. magbodjavou@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Agbodjavou MK, Mêliho PC, Akpi EA, Gandaho WM, Kpatchavi AC. ‘We had to be there, Present to Help Him’: Local Evidence on the Feeling of Safety in End-of-Life Care in Togo. Indian J Palliat Care. 2024;30:168-75. doi: 10.25259/IJPC_66_2023

Abstract

Objectives:

For patients with diabetes and cancer at the end-of-life and their families, the safety sought in end-of-life care leads them to opt for home care. In developing countries where palliative care is not yet effectively integrated into public health policies, factors such as long distances to hospital referrals, lack of adequate infrastructure and shortage of specialised health professionals create a sense of insecurity for people seeking end-of-life care. The present study explored the factors that reinforce the feeling of security and insecurity of family members who have opted to accompany their relatives with diabetes and/or advanced cancer at the end-of-life at home in Togo.

Materials and Methods:

This was an ethnographic approach based on observations and in-depth semi-structured interviews with people with the following characteristics: family members (bereaved or not) with experience of caring for a patient with diabetes and cancer at home at the end-of-life. The data were analysed using content and thematic analysis. This was done to identify categories and subcategories using the qualitative analysis software Nvivo12.

Results:

The results show that of the ten relatives interviewed, eight had lived with the patient. Factors contributing to the feeling of security in the accompaniment of end-of-life care at home by the family members were, among others: ‘Informal support from health-care professionals,’ ‘social support’ from relatives and finally, attitudes and predispositions of the family members (presence and availability to the patient, predisposition to respect the patient’s wishes at the place of end-of-life care and predisposition to talk about death with the dying person).

Conclusion:

The ‘informal support of health-care professionals’, the ‘perception of the home as a safe space for end-of-life care’ and the ‘social support’ of family members contributed most to the feeling of safety among family members accompanying their diabetic and cancer patient family members at the end-of-life at home in Togo. Therefore, palliative and end-of-life care must be rethought in public health policies in Togo to orientate this care toward the home while providing families/caregivers with the knowledge and tools necessary to strengthen care.

Keywords

Feeling of safety

End-of-life care

Feeling of insecurity

Togo

INTRODUCTION

In sub-Saharan Africa, variations in the location of end-of-life care may suggest inequalities in access to health service use that should be addressed by public health interventions.[1] In end-of-life care, ending life at home is seen as a quality marker of a good death.[1,2] Other authors, however, claim that the place of end-of-life care is not the priority, but the ability of families to manage the end-of-life of a family member at home.[3] Recent evidence indicates that the dying person’s family is forced to ‘live in a constantly changing world and balance conflicting interests and dilemmas’.[4]

In contrast to what happens at home, caring for a terminally ill patient in a care institution remains a major challenge for individuals. Organisational dysfunctions such as inadequate infrastructure that does not provide for the family in care institutions and lack of quality human resources and services are barriers to access to end-of-life care in developing countries.[1,5] Second, the interactions between health professionals, the patient and the patient’s family, which should be based on understanding and trust, are excessively formalised.[6] In addition, nurses working with patients at the end-of-life should have appropriate socio-cultural skills and knowledge in end-of-life care.[1] This is not yet a reality in the continuing education of health professionals in West Africa and constitutes a deficiency in the care of patients at the end-of-life.[7] This can result in poorer quality end-of-life care services in hospitals.[7] Therefore, a lack of attention to families’ needs may support the perception of poor quality of care in care institutions,[8] better creates a feeling of insecurity in the care of patients.

The literature on the sense of security of family members has demonstrated the importance for family members to feel secure in their own identity and self-esteem as family members.[9,10] This could be ensured by developing adequate knowledge about end-of-life care and eventual symptom management, ensuring the availability of competent human resources with an open-minded attitude, sensitivity and flexibility of the care team to meet patients’ and families’ needs.[11,12]

Although it is a determinant of quality of care and is recognised as such, knowledge gaps exist in the Togolese context. Few studies have focused on the logic and perceptions of family members, which underlie family members’ sense of safety or lack of security in the use of end-of-life care services. Moreover, the production of such evidence requires the deployment of a combination of research methods based on a rigorous, comprehensive approach. In this article, we make an important contribution by focusing on the elements that underlie the sense of security and insecurity of loved ones in Francophone West Africa. The objectives of this document are as follows: (i) to identify the elements underlying family members’ sense of security and insecurity in the delivery of end-of-life care at home and (ii) to propose a diagram of the influence of family members’ feelings of safety in the delivery of end-of-life care at home.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Type and nature of the research

The present research is cross-sectional, retrospective and qualitative. It is based on in-depth semi-structured interviews with ten relatives of patients, eight of whom have seen their patients die after receiving palliative home care under their responsibility.

Participants and sampling

Interviews were conducted between December 2022 and January 2023 with members of the patient’s family, corresponding to the following criteria: (i) an adult member of the patient’s family receiving care at home and (ii) a member of the family identified as the patient’s main support person for the administration of care at home (by the patient and/or the rest of the family members). It should also be noted that data saturation was reached by the tenth interview. The interviews were conducted following obtaining an exhaustive list of telephone numbers from the Organisation Jeunesse pour le Développement Communautaire (ORJEDEC), a pioneer in palliative and end-of-life care in Togo. Contact was made with the families of patients at the end-of-life with the help of the organisation’s manager. During this meeting, the aim, the problems and the working methodology were explained. The aim of this initial contact was to obtain the consent of the people contacted to participate voluntarily in the research. After giving their written consent to participate in the research, interviews were conducted consecutively. Inclusion criteria were to be a parent, child or family member of a diabetic and/or cancer patient at the end-of-life or deceased due to diabetes and/or cancer aged 18 years or older; to have the experience of caring for a family member of a diabetic and/or cancer patient who did not live permanently in a hospital for palliative and/or end-of-life care. Refusing to participate in the study was considered an exclusion criterion.

Data collection and processing

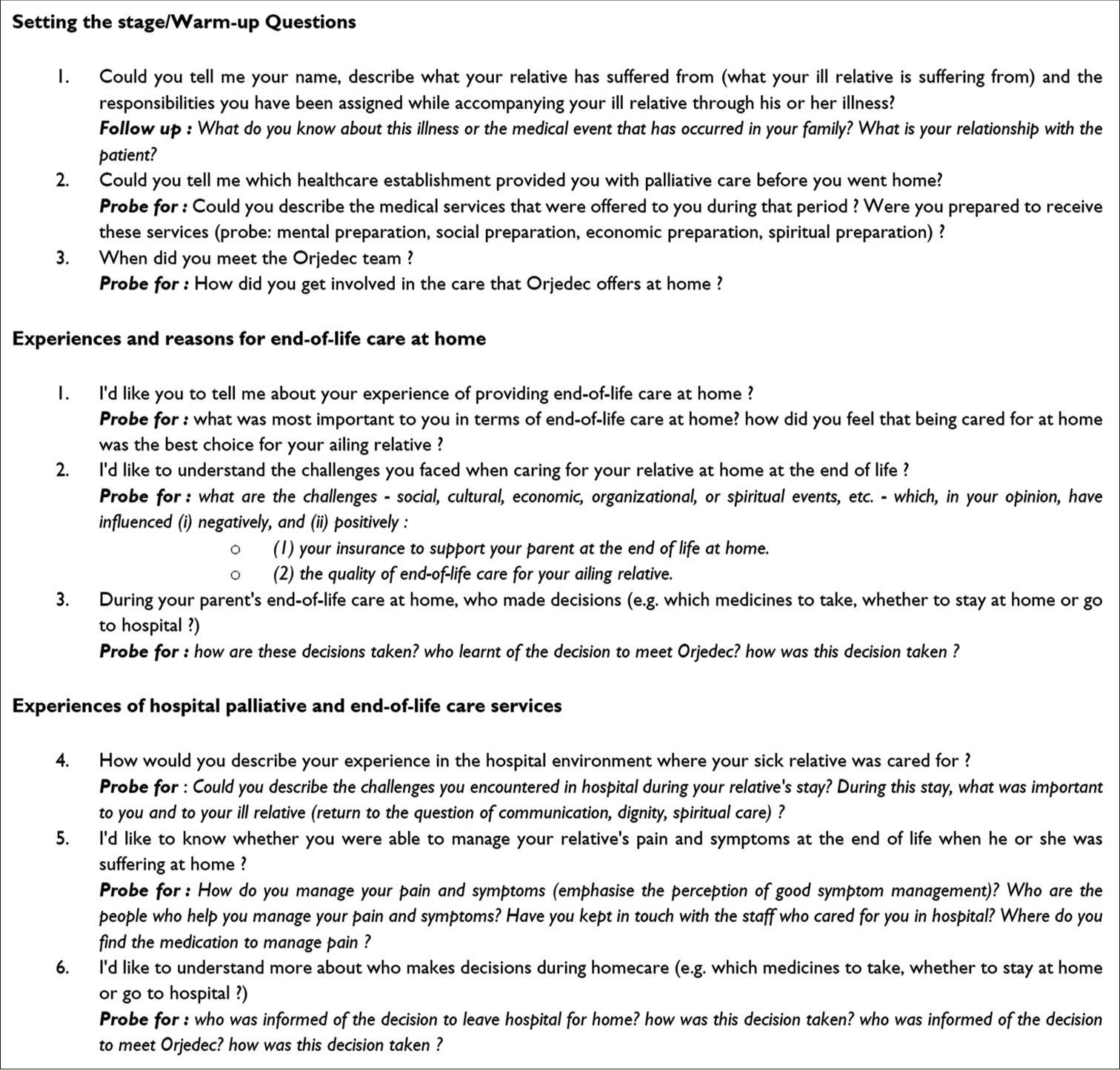

In-depth interviews were conducted using the semi-structured in-depth interview guide by the lead researcher (first author), a public health anthropologist. The principal investigator obtained voluntary consent from participants approached by phone to participate in the study and then shared the list of these participants with ORJEDEC. Unable to control ORJEDEC’s cycle of visits to patients at home, ORJEDEC’s team informed the principal investigator when it would be visiting the home of one of the participants selected for the study. The principal investigator was given the opportunity to administer the interview guide on the day of the visit. In-depth items on the interview guide addressed participants’ experiences and rationales about their attitude to caring for a family member at home at the end-of-life, their experiences of care services for people with diabetes and/or advanced cancer and what made them feel safe or not [Figure 1]. These themes were discussed with the participants when the researcher took part in ORJEDEC’s visits to patients’ homes for care. This fostered a sense of trust between the participants and the researcher.

- Interview guide used by the principal investigator.

The interviews were audio-recorded after the participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

A content analysis was carried out to identify the themes using Nvivo12 software by coding the verbatims. Data saturation was reached in the tenth interview.

Ethical consideration

The Bioethics of Health Research Committee (Comité de Bioéthique de la recherche en santé - CBRS) in Togo has given its approval for the conduct of the research. The research protocol was approved by an expert committee under number 017/2021/CBRS of 07 April 2021.

Confidentiality of data is effective. Loan names have been assigned to each participant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of research participants

Ten family caregivers from ten families participated in the research. About 90% of the research participants lived in the same house as the patient at the end-of-life/death. Most of the participants, 80%, were women. The average age of the research participants was 41.5 years [Table 1].

| Mean age | 41.5 |

| Minimum age | 25 Years |

| Maximum age | 76 Years |

| Sex | |

| Women’s squad (%) | 8 (80) |

| Men’s squad (%) | 2 (20) |

| Sociolinguistic groups | |

| Kabyé (%) | 6 (60) |

| Kotokoli/Tém (%) | 2 (20) |

| Ewé (%) | 1 (10) |

| Mina (%) | 1 (10) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Primary school (%) | 4 (40) |

| High school (%) | 1 (10) |

| University (%) | 5 (50) |

| Relationship with the patient at the end-of-life | |

| Partner/spouse (%) | 6 (60) |

| Child (%) | 2 (20) |

| Parents (%) | 2 (20) |

| Living situation with the patient | |

| Lives/lived in the same house as the patient/deceased (%) | 9 (90) |

| Did not live in the same house as the patient/deceased (%) | 1 (10) |

Source: Survey data, December 2022–January 2023, n: Number

Two out of ten participants still have sick relatives at the endof-life. Participants whose patients have died are all women (n = 8). The most common cancer was liver cancer (88%). The average month since the patient’s death at the interview was 4.6 months. The majority, 75% of the families, received informal visits from health professionals at home [Table 2].

| Mean age | 42.8 |

| Minimum age | 27 years |

| Maximum age | 76 years |

| Sex | |

| Women’s squad (%) | 8(100) |

| Men’s squad (%) | 0 |

| Diabetes type | |

| Diabetes type 2 (%) | 3 (38) |

| Type of cancer diagnosed | |

| Liver cancer (%) | 7 (88) |

| Pancreatic cancer (%) | 1 (12) |

| Average years of cancer diagnosis | 3.7 years |

| Minimum number of years (%) | 5 month |

| Maximum number of years (%) | 12 years |

| Months since death at maintenance | 4.6 month |

| Minimum months | 1 month |

| Maximum months | 10 month |

| Place of death | |

| Home (%) | 4 (50) |

| Hospital (%) | 3 (38) |

| Other (%) | 1 (12) |

| Informal Professional support n (%) | 6 (75) |

Source: Survey data, December 2022–January 2023, n: Number

Sense of security and insecurity: Mapping of influencing factors

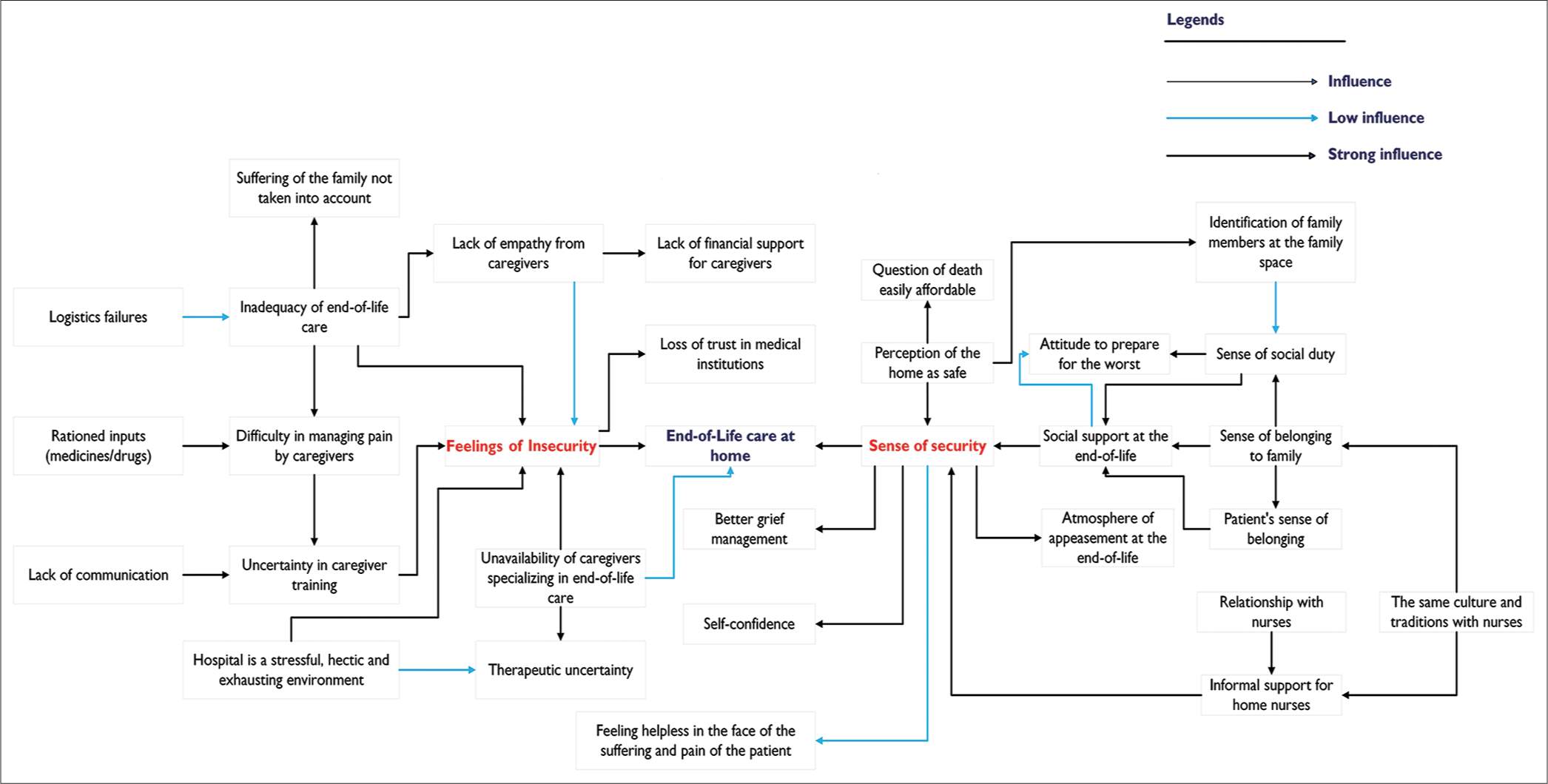

Figure 2 presents a diagram of the influence of family members’ feelings of safety and insecurity in providing end-of-life care at home. It highlights a set of causal interdependencies between the factors underlying the sense of security and insecurity of family members of diabetic and/or cancer patients who have experienced end-of-life care at home in Togo. To structure its presentation and explanation, these factors are categorised into two main groups. The first group corresponds to the factors that have a direct influence on the feeling of security of the family. The second group corresponds to the factors that influence the feeling of insecurity. As each factor in the first and second categories is presented, explanations will be given of the influential relationships of each factor.

- Diagram of the influence of feelings of safety and insecurity among family members of patients with diabetes and/or cancer who received palliative and/or end-of-life care at home.

Description of factors influencing family members’ sense of security

Informal professional support is available

The participants felt that the end-of-life care provided by the relatives ensured safety when they received visits from nurses, who were often friends of the family, outside the institutional setting. Aminata reports:

‘(…) We are in uncharted territory, […] I had my way of seeing him, and he had his way of seeing us now. […] He sees with his pain and suffering, and we see with our hands and ears to listen to him and help him. […]. Fortunately, he had a nurse friend who came to visit him at home. […] Since we left the hospital, she has been coming home. She also advises us on other products that relieve him often but not for long. […]’ (Aminata, interview 5).

This assertion highlights two periods of support. First, the family is lost in the suffering and pain of the patient. Instead of drugs or other products that could alleviate the patient’s pain, they had only their ‘hands’ and ‘ears’. The hand, certainly, to ‘care’ and the ear to ‘listen’ to his complaints and fulfil his wishes. The visits of the nurse announced the second phase. The nurse brings her medical and technical know-how to complement the social assistance provided by the family.

Colette, a family member of a patient with advanced liver cancer, found that the ‘good work’ she did at home in caring for her dying mother was proportional to her relationship with the nurses who came from the same locality as her: ‘(…) My mother did not want to stay in the hospital anymore. […]. When we were still in the hospital, I met two young nurses whose parents came from the same village as us. Moreover, it was during their visits to the village that I asked them to always come to our house to see how my mother was […]’ (Colette, interview 8).

Colette’s sense of security in caring for her mother, who was dying of advanced liver cancer, was reinforced by the ‘informal visits’ of young nurses. This feeling of security was made more valuable by the fact that these nurses shared the same culture with Colette and, therefore, with the patient.

Social support: Attitudes, predispositions and behaviour of families

According to the data collected, several factors related to the family members influenced the feeling of security when caring for their patient at the end-of-life at home. From one family to another, these elements varied and gave rise to a range of perceptions, attitudes and behaviours.

• Sense of social duty to be with the dying person:

All the informants felt that it was important to be at the side of the dying person. The patient’s sense of belonging and the feeling of social duty to be at the bedside of their family is a reassuring element when the course of the disease and its outcome are no longer controllable. This gives confidence and generates a calming atmosphere at the end-of-life. A parent of a dying person explains:

‘(…) It was really important for me to be there for him (…). Sometimes, the drugs were so strong that they must have felt that he was not talking alone but that there were always people around him. (.) Being there was the least I could do. It made me feel better to be there with him at home and to be there for him (Austin, interview 2).

Austin’s ‘physical’ presence with the patient in the last phase of life was crucial as it was a way of reassuring himself that he had not abandoned his parent at a time when he was most needed. On closer analysis, this approach also allows the family caregiver to prepare for the worst. Indeed, Austin could better manage the period of mourning by feeling that he had done his duty and that the death was only the natural continuation of things. Being present and available for the dying person is therefore synonymous with self-confidence, satisfaction with the role played in supporting the patient in the last phase of life and a greater sense of accomplishment. Not being able to be present and available at home to support the dying person gave rise to regrets or remorse on the part of family members. This makes the bereavement period difficult to bear.

• ‘Home:’ A space where patients and families feel safe.

During the interviews, it emerged that the home was the preferred place for end-of-life care or death. The reason was that it was the patient’s wish and should be respected. One interviewee confirmed this:

‘He woke up and told his daughter and me that he wanted to go home to die. […], if that is what he wants, we must respect his wish. […]. Because he said, we’ll feel better as a family. […] In the end, we went back because he was right (Latifa, interview 9). Despite his health and physical condition, the patient had only one desire: To return to his family at home. The family represented a reassuring and safe space for the patient at this time. Otherwise, the home was seen as a ‘safe place’ to end one’s life. It should, therefore, be emphasised that the feeling of belonging to a family and the fact of identifying with the family space reinforces the feeling of security.

• ‘Home:’ A safe space for complex discussions about death.

For the informants, end-of-life care of the late-stage patient is safe and reassuring at home if family members are able and willing to talk about death with the patient. They said that it was necessary to be open and realistic about the remaining life span of the patients and that this was not the period to ‘waste’ time on procedures in the hospital. One informant said:

‘(…) every time I talked about it; He understood something else. […]. Finally, it was with the presence of his pastor that we were able to discuss with him the question of death and all that would follow. […]. I understood that it was only at home that he could talk about his death (Anissa, interview 5).

The sense of security was that at home, the issue of death could be discussed at length between the family and the patient, regardless of the patient’s mood. The family’s willingness to discuss the issue of death with the patient allowed them to collect his last wishes. In Togo, death is considered a taboo, a family secret that can only be discussed in the privacy of the family. Indeed, talking about death brings family members back to conflicts and misunderstandings, long avoided or camouflaged by daily concerns before the event of death.

Description of factors influencing family members’ feelings of insecurity

Hospital: A disturbing environment

The hospital was seen as a ‘turbulent environment’ (4 out of 10 informants), an ‘exhausting atmosphere’ (2 out of 10 informants), and a ‘stressful coming and going’ (2 out of 10 informants). Idrissa recounts his experience:

‘We don’t want to stay in the hospital anymore because the environment was no longer safe (…). We were all upset and tense. (…). And it wasn’t our fault, it was more the stressful comings and goings of the hospital. It was a rhythm that exhausted us. […]. And since we were in a room with other patients, there were too many comings and goings and so were the screams. […]’ (Idrissa, interview 3).

The traffic in the hospitals was tiring. It was a hectic pace of stress and agitation and an exhausting atmosphere that made the family feel uncomfortable. This experience is experienced as an absence of peace and privacy at a time when the patient and family needed it most.

Inadequacy of end-of-life care to the realities of patients and families

In the interviews, two-thirds of the families stated that hospitals do not guarantee that they will accompany the patient at the end-of-life. Accompanying a patient at the end-of-life is a long and expensive activity. What irritates some families is the lack of ‘financial’ empathy on the part of health professionals in the face of the evolution of the patient’s state of health: ‘(…). The saddest thing was that we still had the same expenses at the hospital […]’ (Anissa, Interview 5).

In addition, uncertainty in physician training in palliative medicine, particularly in communication with family and pain management. The experience of Idrissa and his family best expresses it:

‘[…] each visit consisted of a technical and medical observation. […] there was no: Are you all, right? Don’t worry! […], we are all human and beyond the good morning and good evening and therapeutic discussions, the caregivers must think humanly about us who are suffering […]’ (Idrissa, Interview 3).

Idrissa’s words question communication in the caregiver-family relationship around a patient at the end-of-life. Idrissa seems to be able to distinguish between the two. There is the suffering of the patient but also the suffering of families. This is not considered at all in clinical support in hospitals. As a result, two major expectations were identified as contributing to feelings of insecurity in hospital end-of-life care. These included caregivers’ inability to listen to family members and caregivers’ lack of support or empathy during this ordeal.

Need for specialist palliative and end-of-life care professionals

Six family members acknowledged during the interviews the special nature of palliative and end-of-life care in Togo. For most of them, ‘palliative care in Togo is not yet a reality’ (Austin, Interview 2), and they would have to wait a few more years before ‘trusting these hospitals for effective palliative and end of-life care’ (Latifa, Interview 9).

Respondents were also unanimous about the lack of nonspecialised health professionals. For example, the experience of an evacuation of Aminata’s dying relative.

‘[…], I trust the neighbour of the neighbourhood more to evacuate my father to the hospital than the ambulance that screams and never arrives […]. I think a lot of families feel safe at home when it comes to caring for their sick family because these doctors and their cohorts don’t specialise in the issues that concern us’ (Aminata, interview 5).

Aminata’s comments reveal a lack of logistics and qualified human resources for end-of-life care in the management of patients at the end-of-life. What frustrates Aminata is the fact that they are not reactive in case of emergency, which is likely to make users lose confidence.

Medicines rationed by caregivers in hospital care

From the interviews, it emerged that the caregivers acted as if the drugs were not available. Four families mentioned that they felt that they were being ‘pushed around’ in search of morphine. One respondent said:

‘(…) My aunt told me to get the nurse because he was still moaning. The nurse replied as if she was going to arrive later […] but nothing. I went back to the supervisor, who came into the room to make a report and ask a few questions. Then he, too, left, promising that the doctor would come a little later. But nothing. […] We had to run like that apparently because of morphine. Or what? […]’ (Rodolphe, Interview 1).

In Rodolphe’s opinion, the drug treatment for the patient was ineffective. The informant saw this behaviour as a machination by the caregivers not to use all their stock on one patient. Or, according to him, the morphine was not available, which would explain the attitude of the caregivers.

DISCUSSION

Informal visits by health professionals to the home, social support from family members in end-of-life care and medicoorganisational uncertainties in hospitals were identified in this research as the elements that make family caregivers feel either safe at home or insecure in the hospital.

Informal professional supports are based on relationships between caregivers and families. Caregivers find themselves in a position that leads them to new roles: that between the ‘past’ functional role of a caregiver within the hospital and that of a structuring role in the dying person’s family system as a ‘caregiver-friend’ or ‘caregiver from the same sociocultural group’. Informal visits by a health worker in the shoes of a friend or relative in the home constitute a ‘micro-culture’ in this sense.[13] It refers to a mix of knowledge and skills[14] in end-of-life care at home.

The other characteristic of this relationship is ‘trust’. The phenomenon of trust implies firstly the status of ‘caregiver’ recognised by the health system, by the patient and the family. Second, it implies the status of ‘family member’ or ‘family member sharing the same sociocultural identity’. Finally, it considers the attention paid by the ‘caregiver-friend’ to the ‘unhappiness’ that affects the patient and their family. In contrast to our conclusion, a study in Norway rather believes that it is only the status of ‘health professional with specific knowledge and skills’ (palliative care) that underpins the feeling of security of ‘informal caregivers’.[15] This diversity of findings could be understood by the difference between the development of palliative care in Norway and in Togo. The former has formally promoted palliative care at home, whereas, in Togo, this is still far from being the case.

A systematic review of the literature,[1] previous research,[7,16,17] and this study have revealed that palliative and care, in general, is costly, especially in the context of Sub-Saharan African countries where resources are limited in the care of patients and their families. Accompanying a patient at the end-of-life would require recognition of the work (physical, emotional and financial) of families. This must be reflected in a financial revaluation of hospital expenditure. Indeed, for discontinuous hospital stays, it may be ethically ‘complex’ to invoice each hospitalisation or consultation. It is, therefore, necessary to think about a new form of invoicing for the hospitalisation or consultation of these patients.

Inadequate communication, uncertainty in the organisation of end-of-life care in hospitals and ‘complicated’ interaction between health professionals and families are elements of frustration in the hospital setting. It creates a ‘perceived’ insecurity among families and relatives.[18] In this context, it is important to draw the attention of health professionals to the social, cultural and ethical dimensions of caring for patients at the end-of-life. This raises the issue of reforming national systems for training health professionals in end-of-life care.

The home provides a space for the family to talk about the disease, the prognosis and death. This attitude of talking about death with the sick at home is a relief for the family. Several studies have shown that discussions about death with people who do not have much time left to live are hurtful and complicated.[19] Family members often do not know how to start discussions about death with the dying person. Furthermore, without the presence of a religious leader, it is still not clear how the dying person will react to the desire of family members to discuss death issues. This observation could lead to the development of a support that would allow families and caregivers to discuss death both in the hospital and at home.

One of the limitations of the present research is the number of participants interviewed due to the difficulty of recruitment, with some refusals from those contacted. Among the bereaved family members, the absence of a choice of a minimum period (1 month) between the death and the interview creates a memory bias, but it was deemed necessary given the potential emotion generated by recalling the facts to the family. The use of semi-structured, in-depth interviews allowed the research participants to express themselves more freely.

CONCLUSION

This research confirms the importance of the humanistic character of health professionals and the good organisation of end-of-life care in hospitals to give families a sense of security in caring for their patients in the last phase of life. It also confirms that the hospital does not seem to be the preferred place for patients and their families for end-of-life care or death. Insofar as the home seems to provide a sense of security in terms of the informal support of health professionals, family friends, the presence and availability of relatives and the involvement of religious leaders in discussions around death. There is room for improvement in end-of-life care, particularly regarding clinical, organisational and therapeutic uncertainties. It would also seem appropriate to continue the palliative and end-of-life phase at home by diversifying the assistance provided to families and by strengthening the knowledge and skills of nurses.

Acknowledgment

We want to thank the team of Organisation Jeunesse pour le Développement Communautaire (ORJEDEC), who supported us throughout the data collection process.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Bioethics of Health Research Committee (Comité de Bioéthique de la recherche en santé - CBRS), number 017/2021/CBRS, dated 07 April 2021.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Dying in Hospital or at Home? A Systematic Review of the Literature on the Motivations for Choosing the Place of End-of-life for Patients with Chronic Diseases. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2022;9:4246.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of Place of Death in Southwest Scotland 2000-2010: Retrospective Cohort Study. Palliat Med. 2016;30:764-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is Home Always the Best and Preferred Place of Death? BMJ. 2015;351:h4855.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To Live Close to a Person With Cancer-Experiences of Family Caregivers. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51:909-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospice and Palliative Care Access Issues in Rural Areas. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2013;30:172-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trust in the Early Chain of Healthcare: Lifeworld Hermeneutics from the Patient's Perspective. Int J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing. 2017;12:1356674.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What Do We Know about Palliative Support for Women with Chronic Diseases in Benin? For an African Model of Palliative and End-of-Life Care. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2022;10:175.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recognising the Value and Needs of the Caregiver in Oncology. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6:280-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between Bereaved Families' Sense of Security and Their Experience of Death in Cancer Patients: Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:926-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Effects of Community-wide Dissemination of Information on Perceptions of Palliative Care, Knowledge about Opioids, and Sense of Security among Cancer Patients, their Families, and the Public. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:347-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can a Single Question about Family Members' Sense of Security during Palliative Care Predict their Well-being During Bereavement? A Longitudinal Study during Ongoing Care and One Year after the Patient's Death. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18:63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sense of Support Within the Family: A Cross-sectional Study of Family Members in Palliative Home Care. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19:120.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of Carer-Patient Relationships with Regard to Therapeutic Education Practices United States: UPMC; 2015.

- [Google Scholar]

- Between formal and informal: The Face of Supply and Demand for Maternal and Curative Care in the AdjaFon Environment of the Couffo Department in Benin. Rev Esp Territoir Soc Health. 2020;3:43-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Qualitative Study of Bereaved Family Caregivers: Feeling of Security, Facilitators and Barriers for Rural Home Care and Death for Persons with Advanced Cancer. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20:7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difficulties in Accessing Health Care for Poor People Living in Non-Poor Households. Public Health (Paris). 2014;26:89-97.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender and the Development of Palliative Care: Perspectives on the Social and Cultural Burden of Late-Stage Breast Cancer in Women in Benin In: Babadjide CL, Fangnon B, Vissoh SA, eds. Gender - Environment and Sustainable Development in Africa. Cotonou: Viatique; 2021. p. :102-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Return home in palliative care: Interface between the Brazilian and French scenes. Rev Int Soinspalliat. 2018;33:111-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variations in and Factors Influencing Family Members' Decisions for Palliative Home Care. Palliat Med. 2005;19:21-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]