Translate this page into:

We have a Responsibility

Address for correspondence: Prof. MR Rajagopal; E-mail: chairman@palliumindia.org

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

PALLIATIVE CARE STANDARDS FOR HEALTH CARE

If you have been in palliative care long enough in India, the sight of a person with an ugly scar around the neck would not be unfamiliar to you. Hanging is the preferred mode of attempted suicide in our country, and many people are driven to it by unrelieved pain, the extent of which, in many disease states, can be beyond an ordinary human being's power of imagination. The National Crime Records Bureau showed that 26,426 people in the country, suffering from various ailments, chose to end their lives in 2013.[1]

There are many reasons why pain goes unrelieved in India. Although India developed a National Program for Palliative Care in 2012,[2] lack of budget allocation means that it remains a paper tiger. The huge regulatory barrier of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act of India has been simplified by the Indian Parliament in 2014;[3] but it is awaiting implementation by state governments. And to top it all, palliative care is an unknown entity even among medical professionals. In 2014, the Times of India quoted a multicentric study conducted by All India Institute of Medical Sciences, which showed that seven out of ten doctors dealing with terminally ill patients were not aware of palliative care.[4] At least, a million people live with unrelieved pain in India from cancer alone.[5]

Failure to alleviate pain in the context of availability of inexpensive modalities of treatment, in addition to being ethically unacceptable, is also, according to the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, considered “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”[6]

The Economist Intelligence Unit, in 2015, published the Quality of Death Index, which ranked the end of life care (or lack, thereof) across the world. Among 80 countries included in the study, India came 67th. At one look, this may seem an improvement on the 2010 report, where India had ranked 40th out of 40 countries, below Uganda, which was at 39. However, closer study of the report would inform us that India escaped from being at the very bottom, not because of better quality of death, but because there is an atmosphere conducive to growth of palliative care, as created by the formation of India's National Program in Palliative Care and the Amendment of the NDPS Act of India in 2014 though they are yet to be implemented.

The Economist Intelligence Unit's report, while critical of the poor attention to the dying person in India, was appreciative of the developments in the State of Kerala. Kerala has more palliative care than in the rest of the country put together, though only 3% of India's population lives in this tiny state. More than 185 institutions in this state have a doctor and nurse with training in palliative care, stock and dispense oral morphine and most dispense it free to patients in pain. At one glance, this would appear to be a heaven within a sea of suffering; but a closer look would tell us that Kerala has this exalted position only in comparison with the rest of the country. Things are not too rosy in Kerala, either.

On the first of June, 2014, the Times of India reported the sad story of a couple in a hospital in the North Kerala City of Kanhangad, who killed their son before committing suicide. A suicide note said they had decided to take the extreme step because they were unable to tolerate their son's pain.[7] This is not an exceptional situation; most hospitals even in Kerala do not have access to pain relief. Palliative care workers in Kerala see this time and again. My colleagues and I once walked into a newly opened palliative care clinic in the children's department of a major government hospital. We were met by screams from within the new palliative care clinic room. In there was a tiny child who, according to the family, had not slept continuously for more than 15 min at a time, for 3 months. The family later confessed that they had indeed planned mass suicide. They had no choice. The father had lost his job. The mother had lost her mind and was standing like a statue in one corner of the room. A 11-year-old sister of the baby had taken over the job of the mother and was explaining the problem to the doctors. What she lost was her childhood. Two members of the palliative care team, a medical social worker and a senior volunteer, later confessed that on that day, they had made a mental vow never to return to that clinic; they could not bear to see such intense agony of a child.

Paradoxically, that child, when the general condition had begun to deteriorate, had indeed got high-tech care within an Intensive Care Unit. Excellent monitoring systems and a mechanical ventilator were available to the child when life was threatened; yet no solution at all was offered for the unrelieved pain. The child apparently had developed encephalitis as a baby and now had muscle spasms which were the major source of the child's suffering. At the new palliative care clinic, receiving a tiny dose of morphine every 4 h, the child lived and eventually died reasonably pain-free. The father has now got back to work; the mother is receiving psychiatric treatment and the sister is back in school. This is the kind of solution that is possible at very low cost; yet, despite the existence of a state policy, such care does not reach people who need it.

This situation should not have happened in Kerala, which had declared a palliative care policy in 2008.[8] The policy document envisaged introduction of palliative care “at all levels of care” – tertiary, secondary, and primary – as was much later recommended by the World Health Assembly in 2014.[9] Part of this policy was successfully implemented. Every single Panchayat (the smallest unit of local self-government institution, ordinarily having a population of 30,000-50,000) now has a palliative care nurse who has had at least 3 months training. This is clearly a success; equally valued is perhaps the community-base of palliative care structure. Hundreds of nongovernment organizations work in the field of palliative care, members of the community accepting the responsibility for caring for the less fortunate among them. True, there are issues in lack of coordination between the government system and the community-based system. But hopefully, these problems can be overcome. The most disappointing aspect of the implementation of Kerala's palliative care policy is the failure of the system to introduce palliative care into secondary and tertiary hospitals, the vast majority of which, even 8 years after declaration of the policy, do not have doctors trained in palliative care. No wonder, hence, that the child mentioned earlier – and many other children – continued to scream.

In retrospect, one major lacuna in Kerala's palliative care policy was its failure to define standards of care. There is a question often raised: Can a budding palliative care service still afford to have standards of care? The answer is a clear yes. If once we accept that care is the right of the person with the disease and the family, the very acceptance of that responsibility makes it our obligation to provide a certain standard of care. This standard may vary from country to country, depending on availability of facilities. The standards cannot be the same for some low-income countries where many patients never get to see a doctor and for Kerala, where most people get to a doctor if they are unwell. Hence, within the cultural context and availability of resources, some target for minimum standards needs to be set. These standards would form a live document; they would not be cast in stone. The minimum standards, once defined and achieved, then could be followed up with development of grades of levels of standards that the unit can strive to achieve.

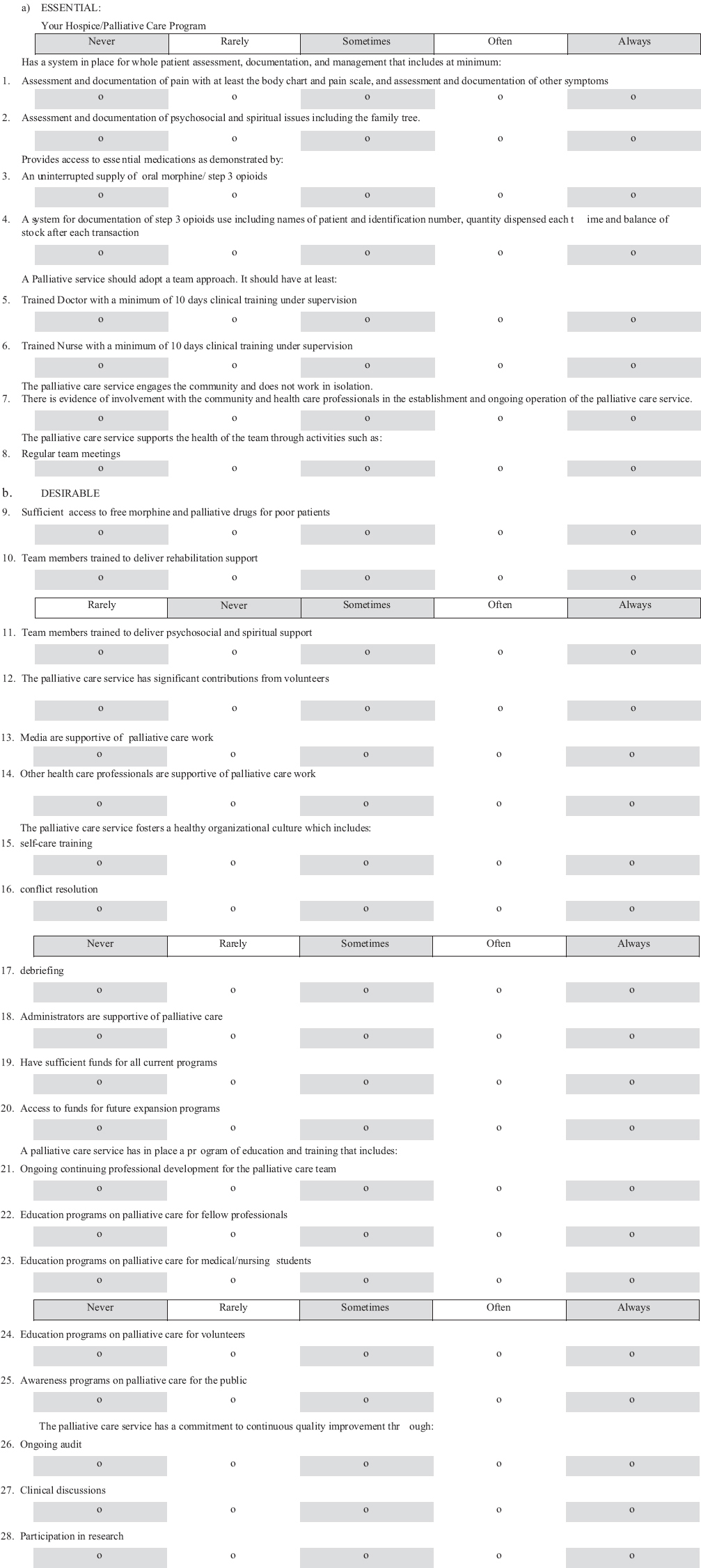

During the years 2005-2006, Pallium India got together a 13-member task force of experts from various parts of the country to develop minimum palliative care standards for India.[10] They decided on eight essential points and 22 desirable points. [Annexure 1: Standards document] The essential minimum standards were modest. They included documentation of symptoms including a pain score and body chart, and use of a family tree and documentation of psycho-socio-spiritual issues. Adequate documentation of Step III opioids was an essential feature, and uninterrupted supply of oral morphine was another. The standards included the presence of a doctor and nurse with at least 10 days of training in palliative care. They also included evidence of the involvement of the community and, as an index of teamwork, regular team meetings.

Looking back, this fits in well with the World Health Assembly Resolution of 2014, which recommended to member countries to “integrate evidence-based, cost-effective, and equitable palliative care services in the continuum of care, across all levels, with emphasis on primary care, community- and home-based care, and universal coverage schemes.”[9]

It has been almost 10 years since the standards were developed. Are they still relevant in their current form? Maybe a revision is necessary. By all means, if that is the general perception, it must be revised. But while we are at it, we possibly need to take into consideration the fact that these perhaps should not stand alone as standards for palliative care but should be considered essential palliative care standards for health care as a whole.

This is certainly not too ambitious a target. Basic palliative care being integrated into health care at all levels is an essential requirement though generally unavailable. The fact that we have allowed such a gap to continue all these years is not enough reason to go on continuing to make the same mistake. Oral morphine is classed as an essential medicine in Government of India's list[11] just as it is in international documents too.[1213] Yet, it is not available in most hospitals in India, whether in the government sector or private.[6]

Palliative care activists in India need to resolve that we shall not allow the present “cruel, inhuman, and degrading” state of affairs to continue. We need a concerted advocacy program through the country, demanding that healthcare system at all levels must include basic palliative care satisfying some minimum essential standards.

Advocacy is not something that comes naturally to most medical, nursing, and allied professionals. However, without it we cannot make progress. The palliative care community in India has to get its act together to reach out to lawmakers and bureaucrats and demand adoption of minimum palliative care standards by the healthcare system as a whole. Naturally, this will mean considerable public and media advocacy, and also significant governmental advocacy.

We now have the opportunity to try to make this happen as the world is ready to review the progress of the “World Health Assembly Resolution of 2014.”[9]

This is an opportunity and also a responsibility. Those who are blind to the problem of pain and suffering have an excuse not to do anything about it. We of the palliative care fraternity have none. We are aware that there is a huge social injustice threatening life with dignity and now that the opportunity has presented itself to us, have the responsibility to try to make a change.

Acknowledgment

I thank Ms. Jeena Manoj for the secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- The Times of India. One in 5 Suicides in India is Due to Chronic Illness. Available from: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/One-in-5-suicides-in-India-is-due-to-chronic-illness/articleshow/45041564.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- Pallium India. 2012. National Palliative Care Strategy. Available from: http://www.palliumindia.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/National-Palliative-Care-Strategy-Nov_2012.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. 2014. Gazette of India No. 17. Available from: http://www.indiacode.nic.in/acts2014/16%20of%202014.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- The Times of India. End-of-Life Care Facility in UP Soon, but no Policy Yet. Available from: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/lucknow/End-of-life-care-facility-in-UP-soon-but-no-policy-yet/articleshow/44779846.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving access to opioid analgesics for palliative care in India. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:152-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- The Times of India. Parents Kill Ailing Son before Committing Suicide in Hospital. Available from: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kozhikode/Parents-kill-ailing-son-before-committing-suicide-in-hospital/articleshow/35912324.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- Pallium India. 2008. Kerala Government Palliative Care Policy. Available from: http://www.palliumindia.org/cms/wp.content/uploads/2014/01/palliative-care-policy-Kerala-109-2008-HFWD-dated-15.4.08.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Assembly. Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Comprehensive Care throughout the Life Course. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-en.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Creation of minimum standard tool for palliative care in India and self-evaluation of palliative care programs using it. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20:201-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Department of Pharmaceuticals, Government of India. 2011. National List of Essential Medicines of India. Available from: http://www.pharmaceuticals.gov.in/pdf/NLEM.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/

- Indian Association for Hospice and Palliative Care. Essential Medicines for Palliative Care. Available from: http://www.hospicecare.com/resources/palliative-care-essentials/iahpc-essential-medicines-for-palliative-care

- [Google Scholar]

ANNEXURE: Annexure 1: Standards audit tool for Indian palliative care programs