Translate this page into:

What is the Public Opinion of Advance Care Planning within the Punjabi Sikh Community?

Address for correspondence: Dr. Amarjodh Singh Landa, Ferrybridge Medical Centre, Knottingley WF11 8NQ, England, UK. E-mail: amarjodh@doctors.org.uk

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aim:

The aim was to gain an understanding of what the United Kingdom (UK) Punjabi Sikh community understands and thinks about advance care planning (ACP). This is in response to evidence showing a lack of service usage by Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups.

Methods:

Surveys containing questions about the impressions of terms, advance decisions for care, do-not-attempt-resuscitation, and lasting power of attorney were taken to targeted community groups; these included community day centers, sporting groups, temples, and social media circles. Surveys were available in both Punjabi and English languages.

Results:

A total of 311 surveys were received in total. There was a 50/50 gender split and a mixed group of ages; 75% were born in the UK and 15% were born in Punjab, India. Only a third had some understanding of what ACP meant. Nearly 50% of the participants did express wishes toward the end of their life, however only a third of the respondents knew how to access services. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was felt to be mandatory by 36%. Sixty percent thought that their decision would be legally binding in relatives who do not have capacity.

Conclusion:

This study showed that wishes for religious rites were common, however many do not know how to make them known. If they do know about services, then people are highly likely to engage with the ACP process.

Keywords

Advance care

ethnic minority

planning

Punjabi

Sikh

INTRODUCTION

Prior to the exit of the British Raj from India in 1947, Punjab existed as a single state. When the British left, they split the Punjab into east and west divisions. The new West Punjab was allocated to Muslims and subsequently became a part of Pakistan; East Punjab was allocated for Hindus and Sikhs and remained a part of India. Prior to this, the three religions were spread throughout the Punjab.

The United Kingdom (UK) Punjabi population was estimated to be 700,000,[1] and the Punjabi language is the third most common spoken in Britain.[2] As an ethnic minority, it is important that barriers to health care are understood and overcome in order to achieve fair treatment. A case that I remember very vividly is regarding an elderly Punjabi gentleman. He had a background of advanced Parkinson's disease and ischemic heart disease. Despite visiting the general practitioner (GP) and neurologist multiple times, there was no discussion regarding end-of-life care or planning for death; as a result, this gentleman ended up in A + E having cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

A search of PubMed using the Mesh terms “Advance Care Planning” and “Ethnic Groups” provided 44 results, of which only two were related to the South Asian community.

In 2009, a study which followed 25 South Asian families through the end-of-life care process showed general poor access to palliative care services. This was due to a lack of nuanced services and occasional racial discrimination, plus poor understanding from the families.[3] A more recent survey[4] done in Canada looked at how the South Asian community viewed advance care planning (ACP); 57 participants were recruited. ACP was associated with organ donation and estate planning rather than end-of-life care. Superstitions regarding talking about death were noted to be a barrier to accessing services. The limitations of this study are very significant. The “South Asian” community is very diverse and contains many different cultures, religions, and ethnicities, therefore the results cannot be interpreted for one specific group; furthermore, over three-quarters of the participants were female, which means an underrepresentation of the male population.

There is a moderately large Punjabi Sikh population in the UK. While evidence has looked at the role of ACP within certain Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups, there has been nothing specific to the Punjabi Sikh community; this is important due to the unique cultural identity and philosophy of the ethnic group. Terms such as “South Asian”[2] and “British Indian” have significant connotations and limitations, which may hinder fair treatment and care. Furthermore, a large majority of services are constrained to medical models and do not account for the spiritual and religious factors that come with ethnic groups.[5] This research aims to discover what the views of ACP are within the UK Punjabi Sikh ethnic minority group.

METHODS

Surveys were created asking questions around the three principles of ACP: wishes at the end of life, decisions to refuse treatment, and making decisions when there is a lack of capacity. The survey was pretested among five health-care professionals and nonhealth-care professionals. Aside from the demographics, questions included the following:

-

What does ACP mean to you?

-

Do you have any preferences or wishes toward the end of your life?

-

Would you be comfortable discussing ACP with your family or medical professional? If not, why not?

-

In the UK, can you request medical help to end your life?

The survey was distributed to various community centers such as sporting groups, elderly day centers, and places of worships. It was further circulated online through social media groups and individuals.

Replies to the survey were excluded if they did not recognize themselves as Punjabi, they did not currently live in the UK, or identified as another religion. While there are nonPunjabi Sikhs in the UK, these were not included in order to gain more specific results with regard to the Punjabi Sikh community.

RESULTS

Over the month of September 2019, there were a total of 321 respondents to the survey, of which 82% were done online. Ten of the online respondents were excluded; seven did not currently reside within the UK and three were not of the Sikh religion. A total of 157 respondents were male, 153 were female, and there was one “other” gender respondent; this gave an approximately equal gender split of respondents. Table 1 shows the number of each respondent by their ages; the average age of the respondents was within the age range of 35–44 years.

| Age group | Number of respondents | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 43 | 14 |

| 25-34 | 90 | 29 |

| 35-44 | 59 | 19 |

| 45-54 | 64 | 20 |

| 55-64 | 32 | 10 |

| 65 plus | 23 | 8 |

| Total | 311 | 100 |

Ideas around ACP and what that meant included “advance directives,” “DNACPR,” and “planning for future ill health.” Only a third of the respondents had an understanding that ACP is planning for future health-related issues, whereas the rest were not sure. Incorrect answers included “good health behaviors for our children” and “research into new diseases.” Each unique answer is provided in Table 2.

| Putting into writing what I would like to have happen to me, should my health deteriorate and I do not have the capacity to make my own decisions |

| Doing an advanced directive and discussing resuscitation |

| Making sure others know my wishes about care, should I lose capacity to make decisions for myself |

| Unsure |

| Putting care in place now for things that can go wrong in future |

| Support with personal and domestic care and hygiene, for example, cooking, washing, dressing, bathing, medicines, shopping, transport, and well-being |

| Putting money aside for care when I get old |

| Research into ongoing health problems |

| To set a better future for our children |

| Planning a comfortable and dignified death |

ACP: Advance care planning

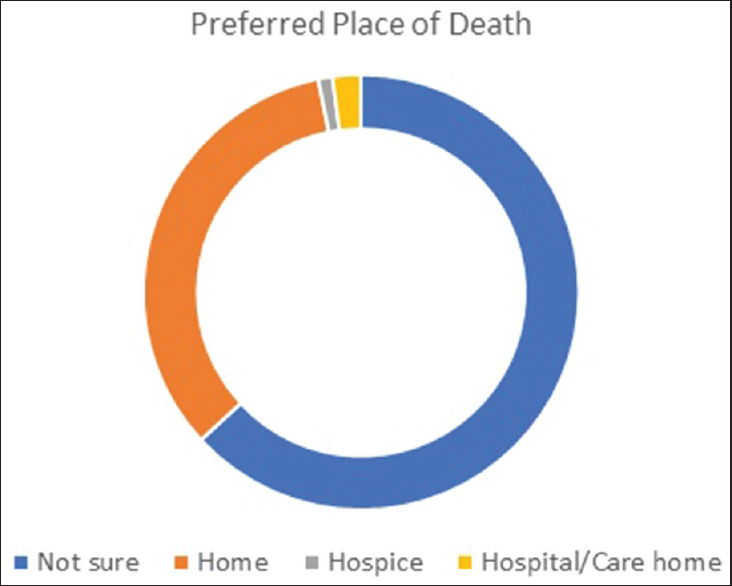

Half of the respondents had already thought about what would happen if a serious illness were to occur; 82% of these had voiced a preferred place of death. There was an overwhelmin choice to be looked after and to die at home, as shown in Figure 1. There was an overwhelming choice to be looked after and to die at home. Interestingly, among the respondents who had declared a preferred place of death, most of them had a vague understanding of what ACP means. This shows that they are likely to give thought to the ACP process if they are aware of it.

- A pie chart showing a percentage representation of answers to the question “Have you thought about where you would like to be looked after toward your final days of life?”

Specific preferences toward the end of life were seen in half of the respondents. Common wishes included dying at home, having specific Sikh prayers and ceremonies, being looked after in a safe environment, organ donation, and euthanasia. Over 80% felt comfortable talking about these wishes with their family and medical staff if required. When asked specifically why one would not like to talk about ACP, there were no unexpected answers; “it's a hard discussion to have,” “not the right time,” and “it's too emotional to think about.” Only one person mentioned “my family would take it as negative thinking.” Importantly, there were no specific cultural barriers, superstitions, or ideologies, which prevented families from talking about death and ACP.

Thoughts around the autonomy of choosing/refusing life-sustaining invasive treatment were different than expected. Twenty-two percent of the respondents thought that treatments such as intubation, ventilation, and life support treatments were mandatory, as did 36% believe that CPR was mandatory; around 10% were not sure whether it could be declined, and the rest understood that it can be refused by choice. I believe that this misconception is largely due to a lack of knowledge around medical treatments and their implications; there was no significant variation between the place of birth and those who thought CPR was mandatory. The legality of euthanasia within the UK was specifically asked about; 10% of the respondents thought that euthanasia was legal. Those who thought it was legal were largely within the 25–34 years' age group and born in the UK.

The next part of the survey focused on patients who lacked capacity. Nearly 72% of the respondents understood that medical decisions would be done collaboratively between the medical team and the next of kin, whereas 16% thought that it would be solely the doctor's decision. This view of a paternalistic doctor was shared more commonly, by those respondents, who were female, over 65, and born in socioeconomically developing countries such as India, Africa, and Pakistan. In the case of a disagreement between the next of kin and the medical team, 60% thought that the next of kins' decision would overrule the medical teams' decision, however only six respondents expanded that this would be because of a power of attorney agreement.

Just under a third of respondents knew that these issues could be discussed further with their GP or medical team.

There was no significant variation in answers according to the respondents' age, gender, or place of birth; apart from the perception that euthanasia is legal, within the UK, among 25–34-year-old Punjabi Sikhs.

Limitations

This research had a large response online which provided a more representative population. The survey online was protected against multiple entries, ensuring that each reply was unique. There are two limitations which could have improved the results. First, a larger sample of older respondents would have given a more equal response in terms of ages, and this may have provided different information. Second, for those respondents who were born outside of the UK, a question could have been included about how long they have been living within the UK. This could then be used to see if the time within the UK has any correlation to the level of ACP knowledge.

DISCUSSION

The survey provided a valuable insight into the current perceptions about ACP within the UK Punjabi Sikh community. It showed that ACP is not very well known throughout the community, however certain preferences and wishes toward the end of life are more common. Religious rites are the most referenced wish, and these include meditation, cremation, and having the ashes spread over flowing water. There were no specific cultural or religious reasons as to why death and end-of-life care should not be discussed among families, and therefore, this should not be a barrier between health-care professionals and patients. The perception around certain treatments, such as CPR and euthanasia, can result in unrealistic expectations, and this should be discussed with the patient and their families as appropriate. Finally, the results suggest a poor understanding about the decision-making process and who can make final decisions, especially in the case of disagreements. This means that more awareness is required with regard to ACP and lasting power of attorney.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Paramjeet Kaur, Bhajneek Kaur, and Rajinder Singh for their support and ongoing generous encouragement. There are no competing interests. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

- House of Commons Hansard Debates for 05 December, 2006. Available from: https://publicationsparliamentuk/pa/cm200607/cmhansrd/cm061205/halltext/61205h0001htm

- 2011. Language in England and Wales-Office for National Statistics. Available from: https://wwwonsgovuk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/language/articles/languageinenglandandwales/2013-03-04#main-language-in-england-and-wales

- Vulnerability and access to care for South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients with life limiting illness in Scotland: Prospective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ. 2009;338:b183.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding advance care planning within the South Asian community. Health Expect. 2017;20:911-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advance care planning for older people: The influence of ethnicity, religiosity, spirituality and health literacy. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26:1946-54.

- [Google Scholar]