Translate this page into:

A Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey of Medical Practitioners in India to Assess their Knowledge, Attitude, Prescription Practices, and Barriers toward Opioid Analgesic Prescriptions

Address for correspondence: Dr. Shalini Singh, Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, D-2, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi - 110 070, India. E-mail: shalin.achra@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Inadequate training of medical practitioners is a key factor responsible for inappropriate use of opioid analgesics.

Aims:

We assessed the current knowledge, attitude, prescribing practices, and barriers perceived by the Indian medical practitioners in three tertiary care hospitals toward the use of opioid analgesics.

Subjects and Methods:

Web-based survey of registered medical practitioner employed at three chosen tertiary health care institutions in New Delhi.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive analysis of survey responses was carried out. Comparative analysis was done using Chi-square test, independent samples t-test, and Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results:

The response rate was 10.4% (n = 308). Two-thirds of the participants (61.7%) had never received formal pain management training, and 86.7% participants would like further training. Most participants (71.1%) agreed that opioids should be prescribed in cancer pain, while 26.3% agreed that opioids should be prescribed in noncancer pain. Half of the participants agreed that SOS (if necessary) dosing schedule (48.4%), low dosage (61.7%), and short duration of use (51.4%) could decrease the harmful effect of opioids. Lack of information about opioid-related policies and addiction potential were identified as the most common barriers to prescribing opioids. Those seeing more patients with chronic noncancer pain come across opioid misuse and diversion more often (P = 0.02). Those who understood addiction were more likely to agree that patients of chronic cancer pain with substance use disorders should be prescribed opioid analgesics (P < 0.01).

Conclusions:

Indian medical practitioners felt the need for formal pain management training. There is a lack of consensus on how to manage the pain using opioid analgesics. Tough regulations on medical and scientific use of opioids are the most commonly reported barrier to prescribing them.

Keywords

Addictive behavior

cancer pain

Internet

opioid analgesics

pain management

surveys and questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Nearly, a third (34%) of the general population in low- and middle-income countries suffers from chronic pain.[12] India has a high prevalence of chronic cancer pain (0.4%) and chronic noncancer pain (19.3%), yet most patients are deprived of essential opioids.[1345] This underutilization disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries.[67] On the other hand, developed nations are facing opioid misuse crisis due to the increasing use of opioid analgesics for chronic noncancer pain.[8] Absence of training and awareness in medical practitioners has been identified as a key factor responsible for inequitable use of opioid analgesics.[9]

In India, restrictive drug supply systems and lack of clear policies on pain management are primary reasons for inadequate use of opioid analgesics.[510] Efforts have been made to streamline standard operating procedures for the prescription of certain opioid analgesics, that is, essential narcotic drugs (END) in India for medical and scientific use.[11] Still, certain issues related to opioid analgesics remain: lack of training of medical practitioners toward use in pain management, concerns about licensing requirements, and fear of legal sanctions upon prescribing.[1213]

Cross-sectional surveys have been conducted in various formats to assess medical practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceived barriers in various regions of the world.[1415161718192021] A 30-year apart analysis medical practitioners from Wisconsin, USA, demonstrated a consistent lack of information about existing regulations and effective pain management strategies.[2223] They had negative attitudes and perceptions toward prescription of opioid analgesics; 90% of the participants believed that prescribing opioid analgesics in those with a history of substance use disorders are illegal. Such findings have been replicated in other regional and nationwide studies from the USA.[132425] Participants have reported insufficient training in pain management and showed reluctance in using opioid analgesics due to tough regulations. Surveys in Europe to assess the knowledge and attitude of medical practitioners regarding pain management and opioid analgesic use have reported similar findings.[2627] In Asia, surveys have been carried out in Bangladesh, Malaysia, Taiwan, Iran, Israel, Korea, China, and Thailand.[1617181920212223] These surveys suggest a lack of clear understanding of the clinical guidelines on pain management and opioid analgesic use, and a majority do not use opioids where indicated. The main barrier was tough regulations. A policy analysis showed weak impetus for training in pain management.[28] We aimed to analyze the knowledge, prescribing practices, attitude, and barriers perceived by the Indian medical practitioners toward the use of opioid analgesics. This information could be used to modify existing training programs and introduce new training modules to improve pain management in India.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study procedure

This is a cross-sectional web-based survey. The inclusion criterion was being a registered medical practitioner employed at one of the three chosen tertiary health care institutions in the National Capital Region. Convenience sampling method was used. Meetings were held with department heads at the hospitals to discuss the study, obtain their support, obtain contact details, and promote participation. Initial E-mail invitations contained two links: one to the study website which provided further information regarding the study and research team, and one to access the survey. Contact was also made through text message with an embedded participation link to increase the response rate.[29] They were assured of anonymity and data protection and were informed about the objective of the survey and approximate time taken to complete the survey. The recipients were asked to open the link and begin the survey if they consented. Nonresponders were sent up to two E-mail and text message reminders each at an interval of 2 weeks and 1 week, respectively, to increase the response rate.[30] Duration of the study was from June 2017 to May 2018. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ethical review boards of each institution.

Questionnaire

It consisted of 33 items in these domains: (1) background information on qualifications, specialty, years of clinical practice, and the past training in pain management; (2) knowledge regarding clinical guidelines for prescription of opioid analgesics in clinical practice; (3) attitude toward prescription of opioid analgesics; (4) barriers perceived to prescribing opioid analgesics; and (5) knowledge about national policies regarding opioids. The questionnaire was designed to take approximately 15 minutes to complete. This time limit falls within the range of ideal web survey filling time of 10 min and a maximum desirable survey filling time of 20 min.[31] Answering all questions was mandatory for successful submission.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. (Armonk, New York, USA: IBM Corp.).[32] Descriptive analysis and cross-tab testing were used to summarize the data and Chi-square analysis, and independent samples t-test was used to determine the relationship between variables. Correlation analysis using Pearson's correlation coefficient was done to measure the correlation between independent continuous variables.

RESULTS

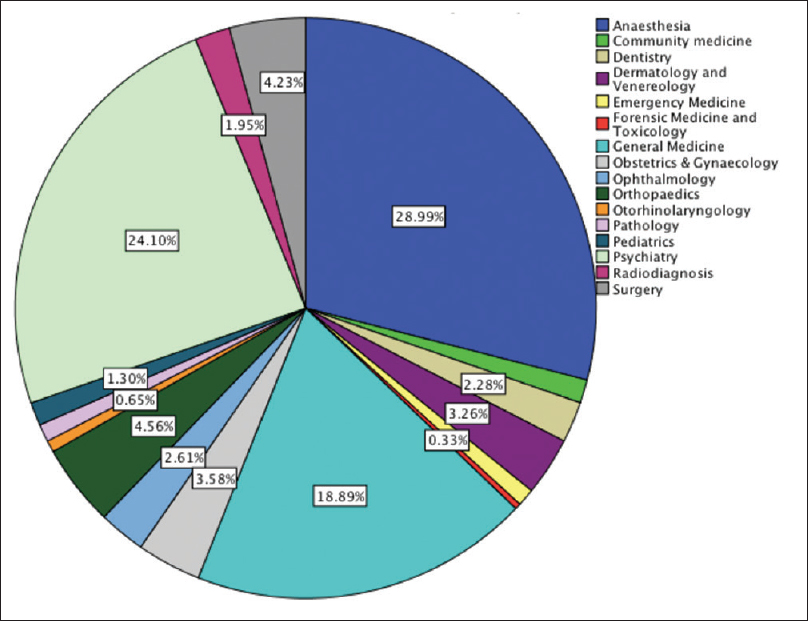

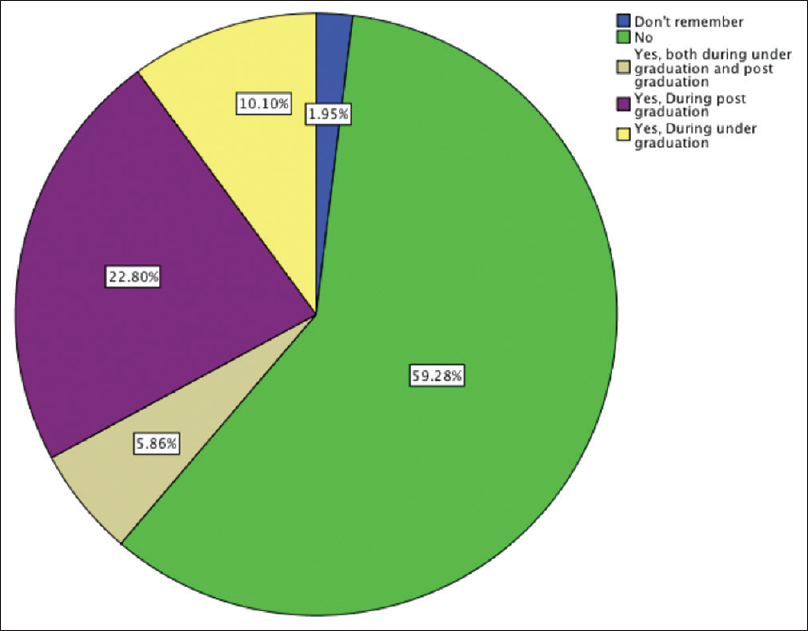

A total of 308 medical practitioners participated in the survey with a response rate of 10.4%. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the specialties that the participants were currently practicing in. Table 1 provides an overview of the participants’ training and current practice. Two-thirds of the participants (61.7%) reported that they had never received any formal training in pain management, while 38.5% of the participants had. There was a significant association between seeing more cancer pain patients in the past year and having received formal pain management training (t = −3.93, P < 0.01) with those who had seen more cancer pain patients having a greater likelihood of receiving training. Figure 2 gives an overview of the past pain management training of the participants and when they received it. Eighty-six percent (86.7%) participants were interested in further pain management training, while 6.8% felt that they didn't need further training. Those who wanted to pursue further training had significantly lesser number of years of clinical practice (15.5 ± 11.1 years) compared to those who did not want to pursue further training (21.5 ± 12.6 years), t (307) = 3.140, P = 0.002. Seventy-eight percent (78.6%) of the participants reported that they had never faced any unwanted attention from the authorities as a result of prescribing opioids.

- Pie chart representing the current medical specialties that the respondents were practicing in

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Designation | |

| Consultant | 163 (54) |

| Senior resident | 57 (18.5) |

| Junior resident | 45 (14.6) |

| Others | 43 (13.9) |

| Number of years of clinical practice, mean (years) | 16.29±11.47 |

| Number of patients seeking treatment for chronic cancer pain seen in the last 12 months* | |

| None | 122 (39.7) |

| ≤10 | 105 (34.2) |

| >10 | 80 (26.1) |

| Number of patients seeking treatment for chronic noncancer pain seen in the last 12 months | |

| None | 49 (16) |

| ≤10 | 97 (31.6) |

| >10 | 161 (52.4) |

*This was calculated as the number of years since completing MBBS final year at the time of responding to the survey

- Pie chart representing the response of respondents to query about the past formal training in pain management

Knowledge

Table 2 gives an overview of the respondent's knowledge, attitude, and prescribing practices regarding opioid use for pain management. There was a significant association between being aware of the World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder and agreeing that opioids should be prescribed to those suffering from moderate to severe cancer pain (χ2 = 335.942, P < 0.01). Those seeing more cancer pain patients were also more likely to be familiar with the WHO analgesic pain ladder (t = 3.82, P < 0.01) and were more likely to believe that opioids were mainstay treatment for cancer pain (t = 3.16, P < 0.01). There was a significant association between believing that administering opioids in an SOS dosing schedule could decrease the harmful effect of opioids such as addiction, and that opioid dosage should be lower than the required dosage so as to avoid adverse effects (χ2 = 12.58, P < 0.01). Those treating more cancer pain patients were significantly more likely to believe that SOS dosing schedule should be used to decrease adverse effects due to opioid use (t = −2.83, P < 0.01), and that opioids should be prescribed at a much lower dose than indicated, so as to avoid adverse effects and addiction (t = −2.27, P = 0.02). They were also more likely to disagree with the statement that an individual is bound to get addicted to prescribed opioids (t = −2.02, P = 0.04). Similar associations were not observed based on a number of noncancer pain patients seen in the past 1 year.

| Question | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Are you aware of the WHO analgesic ladder of pain management? | |

| Yes | 169 (54.9) |

| No | 139 (45.1) |

| Are you aware that the government of India has reclassified some opioids as essential narcotic drugs (end) under the NDPS Act for the purpose of pain management, palliative care, and opioid substitution therapy | |

| Yes | 185 (60.3) |

| No | 122 (39.7) |

| Oral opioid therapy is the mainstay approach for the treatment of moderate-to-severe cancer pain | |

| Agree | 219 (71.1) |

| Disagree | 36 (11.7) |

| Not sure | 53 (17.2) |

| Oral opioid therapy is the mainstay approach for the treatment of moderate-to-severe noncancer pain | |

| Agree | 81 (26.3) |

| Disagree | 161 (52.3 |

| Not sure | 66 (21.4) |

| Administering opioids in an SOS dosing schedule can decrease the harmful effect of opioids such as addiction or adverse effects | |

| Agree | 150 (48.7) |

| Disagree | 110 (35.7) |

| Not sure | 48 (15.6) |

| The opioid dosage patients receive should be much lower than the required dosage so as to avoid addiction or adverse effects | |

| Agree | 82 (26.6) |

| Disagree | 190 (61.7) |

| Not sure | 36 (11.7) |

| If a patient is prescribed opioids analgesics for long, he is bound to get addicted | |

| Agree | 161 (52.2) |

| Disagree | 114 (37) |

| Not sure | 33 (10.7) |

| Opioid analgesics are overprescribed for patients with chronic cancer pain | |

| Agree | 77 (25.1) |

| Disagree | 158 (51.5) |

| Not sure | 72 (23.5) |

| Opioid analgesics are overprescribed for patients with chronic noncancer pain | |

| Agree | 97 (31.6) |

| Disagree | 137 (44.6) |

| Not sure | 73 (23.8) |

| Diversion and misuse of opioid pain medicines are a problem in my practice** | |

| Agree | 111 (36.2) |

| Disagree | 130 (42.3) |

| Not sure | 66 (21.5) |

| I would like to obtain further training and education on the policies and guidelines regarding prescription of opioid analgesics in India | |

| Agree | 267 (87) |

| Disagree | 21 (6.8) |

| Not sure | 19 (6.2) |

**Operational definitions of opioid misuse and diversion were provided in the survey. NDPS: Narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances

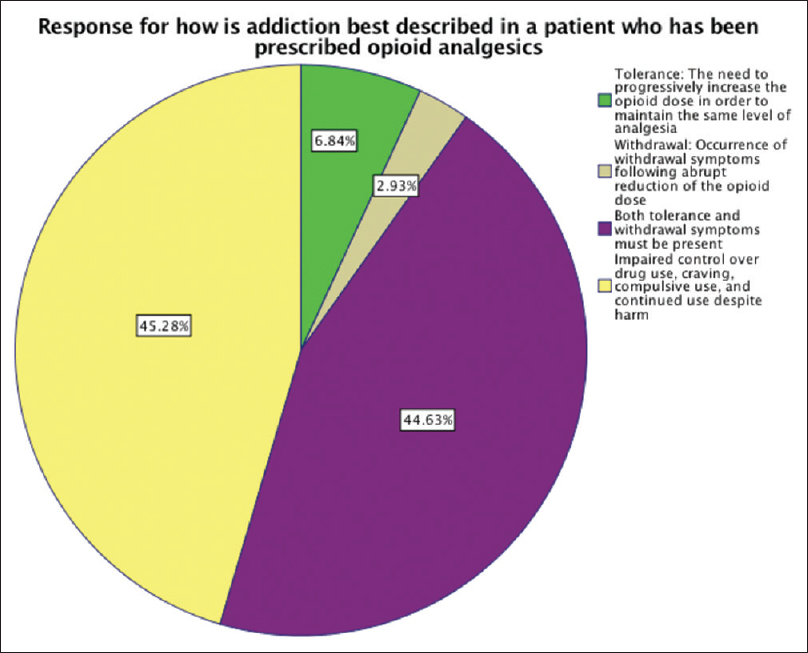

The participants’ knowledge regarding addiction was tested. Figure 3 provides a graphical representation of the response chosen by participants to what they mean by addiction. There was a statistically significant association between having received pain management training and accurately defining addiction (χ2 = 7.59; P = 0.02) with 46% of those who received pain management training correctly defining addiction, while only 32.3% of those who did not receive pain management training correctly defined it. There was a significant association between the perception that long-term use of opioid analgesics might or might not be bound to result in addiction and being aware of the correct meaning of the term addiction (χ2 = 28.26, P < 0.001) with 64% of those who correctly defined addiction disagreeing with the statement while only 34.1% who incorrectly defined addiction agreeing with it. Similarly, there was a significant association between the perception that lower doses of opioid analgesics may or may not be safer to avoid addiction and adverse effects and being aware of the correct meaning of the term addiction (χ2 = 9.8, P = 0.02) with 82% of those who correctly defined addiction disagreeing with this statement and 66.5% of those who incorrectly defined addiction disagreeing with it. The participants were asked if they were aware of what is meant by END as per a recent amendment to the Indian narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances (NDPS) act. About 60.1% of the participants reported that they were aware, while 29.5% reported that they were not aware of the act. The remainder 10.4% reported that they were unsure about its specifications.

- Pie chart representing the response of respondents to query about addiction

Attitude and barriers perceived

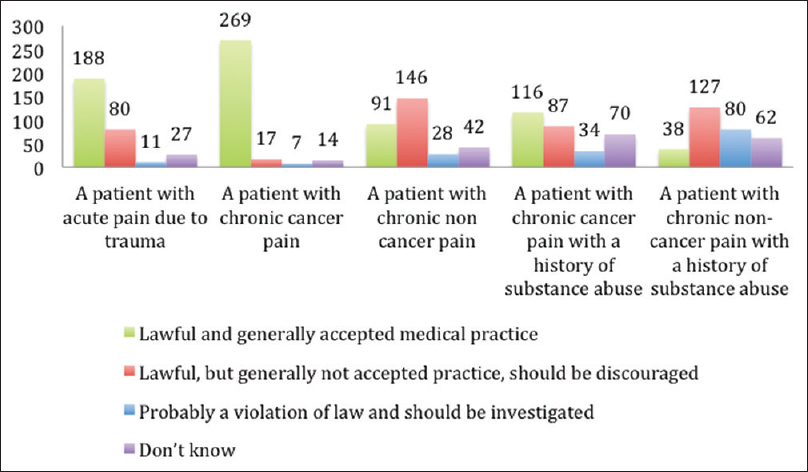

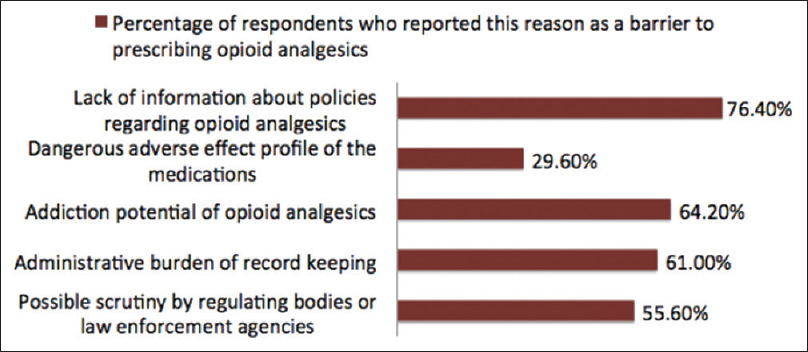

There was a significant association between number of cancer pain patients seen in the past 1 year and believing that opioids are overprescribed for chronic cancer pain with those seeing more of these patients being less likely to believe that it is true (t = 3.29, P < 0.01). Those seeing greater number of patients with chronic noncancer pain were more likely to report diversion, and misuse is a problem in their practice (t = 2.3, P = 0.02). Next, the participants were presented with five clinical situations where opioid prescriptions could be written. They were asked about the clinical and legal acceptability of prescribing opioids in these situations. The distribution of responses is presented in Figure 4 in a graphical format. About 61% of the participants felt that it is appropriate both legally and clinically to prescribe opioids in acute pain due to trauma. In the situation of chronic cancer pain, 87% felt that it is clinically and legally acceptable. This number dropped to 37.7% when the patients in question were those suffering from chronic cancer pain and had a history of substance abuse. Those who correctly identified the definition of addiction were significantly more likely to feel that patients of chronic cancer pain with substance use disorders should be prescribed opioid analgesics (χ2 = 23.94; P < 0.001). In case of chronic noncancer pain, an even smaller proportion of the participants, that is, 29.5% felt that it is accepted practice both medically and legally, while if the scenario was changed to chronic noncancer pain with comorbid substance use; the proportion who felt that it is lawful and generally acceptable medical practice dwindled to 12.3%. Specifically, the participants were asked about the potential barriers to prescribing opioid analgesics in India. Figure 5 is a graphical representation of the responses chosen by participants as barriers experienced by them. The correlation between years of practice and number of barriers perceived was moderate (r = 0.43, P = 0.12) but statistically insignificant. Those who saw more patients with chronic noncancer pain perceived more barriers (r = 0.12, P = 0.04). Fourteen percent of the participants felt that all five options [as shown in Figure 5] were potential barriers to opioid analgesic prescription. While those who felt that they have received inadequate training in pain management perceived more barriers in prescribing opioids, the difference in the number of barriers perceived by two groups was not statistically significant (t = −0.83, P = 0.41). Those who felt that addiction potential was a barrier to prescribing opioid analgesics were not more likely to report that they have not received adequate training in pain management (χ2: 0.21, P = 0.65).

- A graphical representation of responses to queries on attitude toward opioid prescription in various clinical scenarios. Y-axis denotes the number of respondents who chose that response

- Graphical description of the barriers experienced by the respondents for prescribing opioids

DISCUSSION

This was the first web survey of medical practitioners practicing in India on their knowledge, attitude, and perceived barriers regarding prescribing opioid analgesics. The web survey was chosen since it is economical and provides flexibility and privacy.[33] The study population consisted entirely of medical practitioners, so complete Internet coverage of the population being studied can be assumed.[34] The clinical practice profile of the sample indicates that more than half had treated at least ten patients for chronic pain in the past 1 year, so this is a relevant group to assess.

Knowledge regarding the use of opioid analgesics formed an important component of the survey. Various clinical and ethical guidelines have been formulated to guide pain management, especially to avoid the misuse of opioids during the management of chronic pain. However, there is a lack of consensus on how to predict or identify aberrant drug use-related behavior.[353637] Indian medical practitioners have vocalized the need to have culturally appropriate guidelines that are created keeping in mind, the regulatory policies and lack of prior training opportunities.[10383940] The assessment of knowledge showed that most participants (71%) accurately expressed that opioid analgesics should be the mainstay of moderate-to-severe cancer pain treatment, and this response was significantly associated with having prior knowledge of the WHO ladder. Studies in the Southeast Asian region and assessments of prescription patterns for Indian cancer patients too have shown that most of them received opioid analgesics. However, despite severe pain being reported, a large proportion of patients are prescribed weak opioids.[41] Only a small proportion of participants (26.3%) reported opioids as preferred agents to manage moderate-to-severe noncancer pain, and 52.3% felt that they should not be prescribed in such cases. According to the most recent guidelines on the management of chronic pain, the use of opioids for nonmalignant pain is not contraindicated.[35] Rather, pain management needs to be individualized according to the needs of the patient.

One-third of the participants reported having received formal training in pain management, and a majority (86.7%) expressed interest in further training. Those with lesser number of years in clinical practice were more likely to feel that they need further training in pain management. Research suggests that a doctor's initial training has a significant impact on opioid prescribing practices, especially for those who are less likely to receive specialized pain management training during postgraduate course.[42] A lack of opportunities in specialized training in pain medicine and opioidophobia are key obstacles in availing pain management training by the Indian medical practitioners.[43] This finding has been replicated internationally also.[12161719204445] In a multisite survey on Asian medical practitioners (n = 463), medical school training on opioid use was considered inadequate by 30.5% of medical practitioners, and 55.9% indicated ≤10 h of continuing medical education on this subject.[44] In our study, having received formal pain management training was associated with a greater likelihood of defining addiction accurately. Thus indicating that formalized training might help to reduce opioidophobia and aberrant opioid use.[46]

Those who defined addiction accurately were more likely to disagree with statements that long-term use of opioids is bound to lead to addiction and that lower than adequate dosage of opioid analgesics should be prescribed to avoid addiction and other adverse effects. Further, belief that opioids can be safely prescribed to those with chronic cancer pain, and comorbid substance use disorder was associated with knowledge of what constitutes addiction. Comorbid substance use disorder has been associated with an increased risk of opioid misuse.[474849] However, risk factors such as young age, comorbid mental health problems, and poor psychosocial support are equally important before deciding, if opioid analgesics are to be withheld.[35505152]

While there is a lack of consensus on what is the best way to prescribe opioid analgesics, the validity of the WHO pain ladder has withstood time.[5354] Fifty-five percent of the participants reported knowledge of the WHO ladder for cancer pain management, and a majority disagreed that opioid analgesics are overprescribed to patients with moderate-to-severe cancer pain. This is also reflected in a prescription pattern survey done in an Indian palliative care unit, where it was seen that opioids were the most commonly prescribed analgesic, and 90% of patients with moderate-to-severe pain were prescribed morphine.[55] In another Indian study (n = 138), 80% of those cancer pain were prescribed opioids, while strong opioids were used to manage severe cancer pain where indicated.[56] On the contrary, in a multisite survey of Indian tertiary cancer hospitals (n = 1600), it was seen that 67% of patients reported inadequate pain management.[57] In another retrospective chart review (n = 435), it was seen that while opioids were used in 80% instances of cancer pain, the dose used was inadequate and only 31.5% of the patients in severe pain received morphine.[58] About half of the participants noted that opioids are not overprescribed in those with cancer pain, while 25% felt that it was overprescribed. That being said, opioids are the most commonly prescribed analgesics to cancer patients in India tertiary units (47%–80%).[5558] These findings indicate inadequacies and inconsistencies in opioid prescribing practices, which are seen in our study findings too. A majority either agreed or was unsure that opioid analgesics should be prescribed only in SOS doses. A majority felt that prescribing opioids for a longer duration would definitively lead to addiction. At the same time, most participants disagreed with the statement that opioids should be prescribed at a lower dose than indicated to avoid any adverse outcomes. A meta-analysis of studies where opioids were prescribed for ≥6 months found that iatrogenic opioid addiction occurs rarely (0.27%).[59] Certain large-scale cohort studies indicate that a longer duration of opioid use is associated with reduced functionality outcomes and impaired quality of life.[606162] Dose of ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents and early dose escalations are associated with increased morbidity and mortality as per studies.[6364656667] These conflicting attitudinal beliefs mirror the relative lack of evidence on the long-term effectiveness of opioid analgesics and lack of evidence on the efficacy of opioids as part of a multidisciplinary treatment program.

The participants were asked if they are aware of the END amendment in the NDPS act. Around 40% of the participants were either unaware of or wrongly identified the key provision of the END amendment. This is a problematic finding in light of the fact that the Indian government has recently amended the NDPS act to increase the availability of narcotics and guidelines on how to stock END as per the amended act have been recently published.[11] There is an increasing demand to disseminate information on ENDs and restructure medical education to include pain management and palliative care.[6869] Another contributory factor to reduce awareness on ENDs could be that its implementation faces bureaucratic delays.[10]

Access to palliative care in India is facing challenges, a formidable one being lack of easy access to opioid analgesics.[69] The study participants reported a lack of knowledge about opioid-related policies, administrative hurdles in prescribing opioids, and fear of scrutiny by law enforcement bodies to be the most common barriers to prescribing opioids for pain management. A recent review of the Indian literature also showed that stringent regulations on opioid analgesics and lack of awareness and prescribing practices and attitudes of Indian medical practitioners are acting as major deterrents to the treatment of chronic pain in India.[45] Complex rules about opioid prescription and increased paperwork have impeded optimal opioid use in Poland since the past decade.[70] A need assessment study on palliative care education for medical undergraduates (n = 326) in India showed that morphine was considered to be addictive in a palliative care setting by 89% of the participants.[71] In this survey too, the addiction potential of opioids was a commonly perceived barrier to prescribing them. A recent nationwide survey shows that about 1.08% of the Indians aged 10–75 have reported nonmedical use of prescription drugs.[72] This is low when compared to rates of use in Europe and the United States.[7374] One of the factors could be low prescribing rates due to high-perceived risk of addiction and other adverse effects. Negative connotations regarding analgesic therapy (especially morphine) for chronic pain have been seen previously in Indian patients (n = 59) as well as palliative care specialists (n = 28).[75] A majority of participants disagreed or were unsure about diversion and misuse of opioids being a problem in their practice. Research too shows lack of discrepancy in the Indian system of morphine production and distribution.[76] Current epidemiological research does not indicate a predominantly iatrogenic etiology of prescription drug abuse in India.[77]

This survey has certain limitations. First of all, purposive sampling was done, and the survey was limited to a small sample size (n = 308) in three tertiary hospitals in the National Capital Region. This reduces the generalizability of the study sample. The response rate (10.4%) was low despite two reminders being sent when compared to response rates of medical practitioners to web surveys.[78] An analysis of incomplete survey responses might have increased the power of the study. Assessment of knowledge of government policies was limited to a single question on the “END” amendment and could have been more detailed. Finally, the researchers cannot rule out responses as a result of the survey link being shared by recipients. Despite these limitations, this survey helps to understand the scope of the work to improve pain management training in India.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The current knowledge, attitude, and prescribing practices of Indian medical practitioners indicate that there is room for improvement. They have expressed a need for further pain management training and most report regulatory and policy hurdles in prescribing opioids. While most agree that it is appropriate to prescribe opioids for moderate-to-severe cancer pain, the responses about prescription patterns indicate a lack of clarity about dosing and length of treatment with opioids. General consensus needs to be built on how to use opioid analgesics in India, and pain management should be stressed upon in the medical undergraduate curriculum. Further, research on specific knowledge lacuna highlighted in this study would help fine-tune the government policies and training programs concerned with the medical and scientific use of opioid analgesics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- The prevalence of chronic pain among adults in India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:472-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of the global burden of chronic pain without clear etiology in low- and middle-income countries: Trends in heterogeneous data and a proposal for new assessment methods. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:739-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of chronic pain, impact on daily life, and treatment practices in India. Pain Pract. 2014;14:E51-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer pain management in developing countries. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:373-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global disparities in cancer pain management and palliative care. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115:637-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opioids – OECD. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/opioids.htm

- Use of and barriers to access to opioid analgesics: A worldwide, regional, and national study. Lancet. 2016;387:1644-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Access to pain relief and essential opioids in the WHO South-East Asia region: Challenges in implementing drug reforms. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2018;7:67-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Latest Circulars | Department of Revenue | Ministry of Finance | GoI. Available from: https://dor.gov.in/circulars

- Cancer. 1992;70:1438-49.

- Physicians’ attitudes toward pain and the use of opioid analgesics: Results of a survey from the Texas cancer pain initiative. South Med J. 2000;93:479-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating resident physicians’ knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding the pain control in cancer patients. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2015;8:1-0.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary care physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding prescription opioid abuse and diversion. Clin J Pain. 2016;32:279-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- What doctors know about cancer pain management: An exploratory study in Sarawak, Malaysia. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2006;20:15-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicians’ practice and attitudes toward cancer pain management in Korea. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:463-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer pain: Knowledge and attitudes of physicians in Israel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:266-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes and barriers of physicians, policy makers/regulators regarding use of opioids for cancer pain management in Thailand. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2013;75:201-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of prescription of morphine for severe cancer pain by physicians in Korea. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:966-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians knowledge and attitude of opioid availability, accessibility and use in pain management in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2014;40:18-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wisconsin physicians’ knowledge and attitudes about opioid analgesic regulations. Wis Med J. 1991;90:671-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opioid analgesics for pain control: Wisconsin physicians’ knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and prescribing practices. Pain Med. 2010;11:425-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influences of attitudes on family physicians’ willingness to prescribe long-acting opioid analgesics for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Clin Ther. 2007;29(Suppl 11):2589-602.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management. A survey from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:121-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncologists and primary care physicians’ attitudes toward pain control and morphine prescribing in France. Cancer. 1995;76:2375-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- What do Greek physicians know about managing cancer pain? J Cancer Educ. 1998;13:39-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physician continuing education to reduce opioid misuse, abuse, and overdose: Many opportunities, few requirements. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:100-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Text message link to online survey: A new highly effective method of longitudinal data collection. Contraception. 2017;96:269.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: A systematic review. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26:132-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2019. SPSS Statistics – Features. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics/details

- Web surveys versus other survey modes: A meta-analysis comparing response rates. Int J Market Res. 2008;50:79-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using the internet to conduct surveys of health professionals: A valid alternative.? Family Practice. 2003;20:545-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – united States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: Prediction and identification of aberrant drug-related behaviors: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2009;10:131-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinical ethics approach to opioid treatment of chronic noncancer pain. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17:521-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence and consensus recommendations for the pharmacological management of pain in India. J Pain Res. 2017;10:709-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analgesic prescription patterns and pain outcomes in Southeast Asia: Findings from the analgesic treatment of cancer pain in Southeast Asia study. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1-0.

- [Google Scholar]

- Addressing the opioid epidemic: Is there a role for physician education? Am J Health Econ. 2018;4:383-410.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aspiring pain practitioners in India: Assessing challenges and building opportunities. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:93-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current practices in cancer pain management in Asia: A survey of patients and physicians across 10 countries. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1196-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Addressing the barriers related with opioid therapy for management of chronic pain in India. Pain Manag. 2017;7:311-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pseudoaddiction: Fact or fiction? An investigation of the medical literature. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2:310-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of opioid medications for chronic noncancer pain syndromes in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:173-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: An updated review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse: Part 1. Pain Physician. 2017;20:S93-109.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of opioid medications in patients with chronic pain and risk of substance misuse. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:377-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk for prescription opioid misuse among patients with a history of substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127:193-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is the WHO analgesic ladder still valid? Twenty-four years of experience. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:514.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of World Health Organization guidelines for cancer pain relief: A 10-year prospective study. Pain. 1995;63:65-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prescription pattern of analgesic drugs for patients receiving palliative care in a teaching hospital in India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:63-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analgesic and opioid use in pain associated with head-and-neck radiation therapy. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:176-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors and prevalence of pain and its management in four regional cancer hospitals in India. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opioid-prescribing practices in chronic cancer pain in a tertiary care pain clinic. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:222-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD006605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: A retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:425-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: The role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:557-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system. Addiction. 2010;105:1776-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- A detailed exploration into the association of prescribed opioid dosage and overdose deaths among patients with chronic pain. Med Care. 2016;54:435-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing risk for drug overdose in a national cohort: Role for both daily and total opioid dose? J Pain. 2015;16:318-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:686-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dose escalation during the first year of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. Pain Med. 2015;16:733-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methadone is now available in India: Is the long battle over? Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:S1-S3.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-of-life care and opioid use in India: Challenges and opportunities. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3:683-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accessibility of opioid analgesics and barriers to optimal chronic pain treatment in Poland in 2000-2015. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:775-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care awareness among Indian undergraduate health care students: A needs-assessment study to determine incorporation of palliative care education in undergraduate medical, nursing and allied health education. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:154-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- on Behalf of the Group of Investigators for the National Survey on Extent and Pattern of Substance use in India. In: Magnitude of Substance use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; 2019.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in the European union. 2016. BMC Psychiatry. 16:274. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0909-3

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among US adolescents: 1976-2015. Pediatrics. 2017;139 pii: e20162387

- [Google Scholar]

- Associations to pain and analgesics in Indian pain patients and health workers. Pain Manag. 2015;5:349-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Type of opioids injected: Does it matter. A multicentric cross-sectional study of people who inject drugs? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015;34:97-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:32.

- [Google Scholar]