Translate this page into:

A Qualitative Exploration of Caregiving in Advanced Dementia: Caregiver Perspectives on Unmet Needs in Low- and Middle-income Setting

*Corresponding author: Priya Treesa Thomas, Department of Psychiatric Social Work, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. priyathomasat@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Objectives:

The complex and varied needs that people with dementia experience as they approach the advanced stage are context-specific and often unfulfilled. Caregiving is usually family-led and at home, with limited institutional support in low- and middle-income countries like India. The beginning of advanced stages can go under-recognised in the avalanche of overall caregiving demands unique to the prolonged disease trajectory. Limited understanding exists of the unmet needs at this stage. The present study aimed to gain insight into the caregivers’ experiences and unmet needs in advanced dementia.

Materials and Methods:

A qualitative exploratory study with semi-structured interviews was conducted. Eight bereaved primary caregivers of people with dementia who were registered in the Cognitive Disorders Clinic and approached through the recently initiated Neuropalliative care clinic in a tertiary hospital in South India were cared for at their own homes till the end and were interviewed telephonically. A semi-structured interview guide was used, but the interviews were generally participant-led. The interviews with the caregivers were transcribed and analysed manually using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results:

Participants acknowledged the need for comprehensive care management with a holistic approach as the disease advances. The overall theme from the caregiver interviews was unpreparedness for advanced dementia care, which encompassed informational, emotional and social support, multifaceted care requirements, assistance with daily activities, support for caregiving, symptoms requiring better management, cultural aspects of care and the need for future care planning.

Conclusion:

In the absence of organised advanced care support for dementia, recognising the challenges faced by the informal caregivers and providing targeted support enhances the quality of care and acknowledges the crucial role caregivers play in facilitating a dignified and compassionate end-of-life.

Keywords

Advanced care

Caregiving

Dementia

Income setting

Low-and-middle qualitative exploration

Unmet needs

INTRODUCTION

The growth of the elderly population in the world has resulted in a considerable increase in the incidence of disabling disorders and cognitive problems.[1] A major contributor to serious and progressive disability is dementia.[2] The number of people with dementia is estimated to increase from 57.4 million cases globally in 2019 to 152.8 million cases in 2050. The increase is recognised to be more substantial in low- and middle-income countries where the health systems are grappling with the double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. India faces an alarming potential increase in the number of people with dementia.[3]

An estimated 7.4% of people (8.8 million) aged 60 years and older live with dementia in India.[4] Low- and middle-income countries have unequal distribution of healthcare services, and public healthcare systems are fragmented and concentrated more in urban areas.[5] The healthcare focus is predominantly biomedical, with less recognition of organised social care support.[6] This leads to the immediate family members taking up multiple roles and becoming caregivers, which results in a severe caregiver burden. India, as in other Southeast Asian communities, has a family-based culture; younger family members are typically expected to be responsible for the care of older family members.[7] The changing demographics are putting the current system to the test, though, as a result of the shifting modern social structure away from the extended joint-family system and toward nuclear families.

People with dementia have various needs; the early stages are characterised by adaptation to the illness and functional rehabilitation, while the later stages have more advanced care needs. Most people with dementia prefer to remain at home for as long as possible, placing great demands on family caregivers. Care provided by family members remains the mainstay for dementia, and with the uncertain trajectory of dementia, caregivers often struggle to navigate the advanced stages well.[8] Providing care, pain relief, and management of other advanced-stage symptoms in patients by family members puts a lot of pressure on them[9] resulting in a family crisis. Effective participation of informal caregivers in planning comprehensive care is of utmost importance because they play a critical role in providing an appropriate environment as well as high-quality care for the patients.[10]

It is recognised that people in advanced stages of dementia require specialist care to improve comfort and quality of life.[11] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that palliative care should be holistic, meeting the physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs of the person with dementia. The care has to be contextualised to the unique, intertwining individual, familial, social and systemic factors within which the person is embedded. There is an emphasis on adopting a person-centred approach to care, involving the people with dementia and their caregivers, their views on treatment options and care provision, while the person still has the ability to make decisions and communicate effectively.[12]

Most of the time, the care providers, including the staff in nursing homes, lack knowledge about dementia, preventing early identification and care. Moreover, systematic challenges in healthcare, such as a lack and shortage of trained staff and unavailability of the required medication, also act as barriers to getting treatment and care. These problems are markedly more faced by people who hail from rural backgrounds.[13]

Unmet dementia-related advanced care demands put a person at higher risk for negative outcomes,[14] worse quality of life,[15] placement in a nursing home and even death. Earlier studies on the unmet needs of dementia demonstrate a high level of care needs, including personal care, household tasks, behaviour problems and supervision.[16] The needs have remained unmet or have been met inappropriately as the disease progresses to advanced stages.[17-19] The present study aims to gain insight into the caregiver’s perception of the unmet needs during advanced dementia care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A qualitative exploratory study using semi-structured interviews was conducted among eight bereaved primary caregivers of people with dementia. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines[20] were used to guide all research procedures [Supplementary File 1]. A social constructivist view has been adopted as it holds the assumption that individuals develop subjective meanings of their experiences – meanings directed toward certain objects or things.[21]

Participants and setting

Eight primary caregivers (3 males and 5 females) of people with dementia registered in the Cognitive Disorders Clinic (CDC) and approached through the recently initiated Neuropalliative care clinic in a tertiary hospital in South India were recruited. The Neuropalliative clinic was started in November 2021 to provide multidisciplinary neuropalliative care to people with a diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorders. The participants in the CDC registry were contacted over the phone if they had lost their loved one at least 3 months and not more than 6 months before. Those who had given consent for audio recording were scheduled for an interview at their convenience. The data were collected between April and June 2022. Participants were selected purposefully to ensure that individuals with specific characteristics, experiences or knowledge relevant to the study’s focus are included. The study received ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Verbal consent was obtained from the caregivers, and each consent interaction was audio recorded before the initiation and audio recording of the interview. Data saturation was achieved with eight participants, which ensured that the study reached a point where no new information or themes were emerging, indicating that a thorough exploration of the topic had been achieved. This approach allows for a robust analysis that is grounded in the data.

Context and procedure

The first author, a trained psychologist and project coordinator with a doctoral degree and over 4 years of experience in mental health and neuropalliative care, conducted the interviews. She is knowledgeable in qualitative research methodology. The primary research team has extensive clinical and research experience in dementia, endof-life care and palliative care. A semi-structured interview guide was prepared to guide the interviews, developed through review and interviews with the experts working with dementia. The guide was validated by the experts from the multidisciplinary team [Box 1]. The interviews were conducted in English, and field notes were taken during the interview. Each interview lasted for about 45 min to an hour. The interviews were participant-led, thus ensuring rigor. Probe questions and prompts were used only when necessary. The relationship was established before the study’s commencement, and the participants were informed about the researcher as well as the research purpose. There was no one else present besides the participants and researchers during the study. The repeat interviews were not conducted. The study design did not include follow-up sessions with participants, focusing instead on the initial interviews to gather the necessary data. The field notes were used to capture additional observations, contextual details and researcher reflections that complemented the data collected through the interviews.

Analysis

The interviews were transcribed, the identifying information was removed, and new alphanumeric codes were given. To ensure consistency and accuracy, the first author undertook the transcription and translation of the narrative data. She repeatedly read the transcripts to familiarise herself with the breadth and depth of content, as well as searched for meanings and patterns emerging from the transcribed information.

Thematic analysis was done manually according to the guidelines given by Braun and Clarke[22] which provides an interpretation of collected data while acknowledging the subjectivity of the researchers’ perspectives. Initial codes were made from the transcripts by the first author, and it was independently reviewed and analysed by the second author. Any difference in opinion was resolved through discussion. Peer debriefing was done regularly. Once the codes were finalised, overarching themes were generated. Mapping of themes was attempted to bring out perceptions on unmet needs.

RESULTS

The sociodemographic and clinical details of the participants are given in Tables 1 and 2.

| Participant (patient caregiver) | Age | Gender | Occupation | Relationship with the patient | Bereavement duration (in months) at the time of the interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 45 | Female | Teacher | Daughter | 4 |

| PC2 | 51 | Female | Housewife | Wife | 5 |

| PC3 | 47 | Male | Business | Son | 3 |

| PC4 | 42 | Female | Housewife | Sister | 5 |

| PC5 | 39 | Male | IT Professional | Son | 3 |

| PC6 | 38 | Female | Housewife | Daughter | 4 |

| PC7 | 62 | Female | Bank officer-retired | Wife | 4 |

| PC8 | 38 | Female | IT professionals | Daughter | 3 |

| Patient | Diagnosis | Gender | Duration of illness (in years) | Age of the patient at the time of death | Cause of death | Place of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FTD | Male | 9 | 70 | Pneumonia | Hospital |

| 2 | Vascular dementia | Male | 5 | 62 | Unknown | Hospital |

| 3 | Dementia | Female | 12 | 75 | Respiratory distress | Hospital |

| 4 | FTD | Female | 8 | 72 | Respiratory distress | Home |

| 5 | Vascular dementia | Male | 10 | 72 | Pneumonia | Hospital |

| 6 | Vascular dementia | Male | 8 | 75 | Cardiac arrest | Home |

| 7 | FTD | Male | 7 | 69 | Pneumonia | On the way to the hospital from home |

| 8 | FTD | Female | 9 | 81 | Unknown | Hospital |

FTD: Frontotemporal Dementia

Unpreparedness for end-of-life care

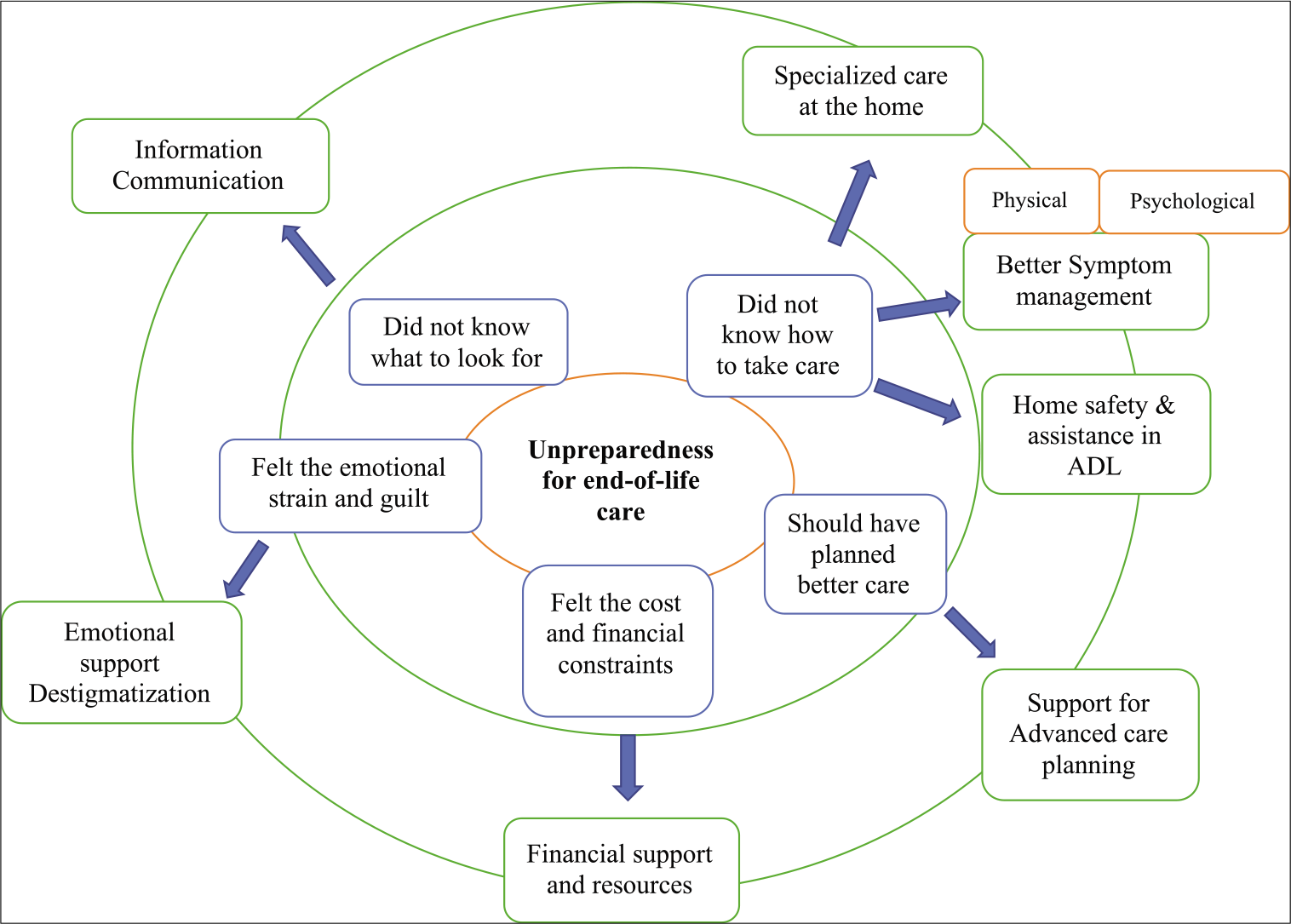

The overall theme that emerged from the interviews was the total unpreparedness for end-of-life care. Caregivers were not able to recognise when the illness was advancing to the end of life and were completely unprepared for the same. They emphasised the necessity for informational, psychological and emotional support through the process of dealing with the approaching end. Participants felt that they could have better cared for themselves and the patient if they had the necessary training and expertise to recognise and care for patients toward the end of their lives. This need was felt over and above the emotional distress they went through during the bereavement period. The major needs fell into the areas that are described below, aligning with the themes that came up in the interviews [Figure 1].

- A thematic map of caregivers’ unmet needs and strategies to address them

Informational, emotional and social support

Not knowing what to expect

The participants did not know what to look for as the illness progressed. A strong need was expressed by the caregivers for basic information on dementia, including its causes and risk factors, recognising signs of worsening, available treatment options and their expected outcomes, to be better prepared about what to realistically expect, thereby allowing for informed care decision-making and better management of their relative with dementia. The need for ‘hands-on’ information on handling unique situations that periodically arise with the deterioration of the illness was felt to be unmet.

The problem is that…. they can’t tell you exactly what to do (what to look for as the end is nearing). When I asked the doctor, he said, ‘You need to notice yourself.’ He said that my mother’s condition would get worse after six to nine months, but he did not tell me how to deal with it either (PC6, F)

Emotional strain and guilt

Caregivers experienced several psychological stressors on a daily basis as the care management of their relative with dementia became more strenuous. Caregiving duties and their own health imposed physical strain and limitations on themselves. More challenging than the physical burden was the perceived inability to provide optimum care for their loved one, which was felt as a greater cause of emotional burden and guilt. This was evident during the end stage when the caregivers often felt isolated and helpless.

…….But yes, there was the feeling that you are alone. It is a feeling that you are alone, my dad can’t make any decision anymore, I will be alone, and you don’t have anyone to help you. I felt like a little child. (PC1, F)

In addition, the effort to manage an uncertain future with the unstable, financially demanding and evolving nature of the illness often led to anxiety. Since caring for a person with dementia was tedious and challenging, informal caregivers felt depressed with little hope for the future and were tired of the constant demands of caregiving, though they expressed ambiguity about the concept of respite inpatient care.

If I took him to a nursing home for a month, it’d do me a lot of good, although I don’t know. I wouldn’t feel comfortable. (PC3,M)

Multifaceted care requirements

Many of the caregivers felt the need for specialised care for the patient, which is often ignored. The need for multidisciplinary care that varied at different stages till the end of life was expressed. The expressed needs also varied: rehabilitation care, psychological care, visits to different specialists and provision of care services by day-care centres are a few.

My dad was at home throughout till he died. I realised that he needed full-time care in the last stage. At that time, I used to think that if someone from the day-care centre could come and care for my dad would be helpful. I searched in many places, but couldn’t find (PC1, F)

Specialised care at home

Caregivers had the opinion that in the last phase of life, patients faced increasing challenges in doing their daily activities as time went by. Caring for the patients in the home was tough for many caregivers to handle by themselves, showing the requirement of a trained home care team to meet the need.

I was finding it difficult to manage the sores which she (mother) got in the last stage. Every time I need to take her to the hospital to clear this. If a trained nurse can do it at home, things would be a little easier. (PC1, F)

Accessible and appropriate support facilities

Caregivers expressed several areas for improvement in care for dementia patients that covered accessibility and affordability of the available care options. They mentioned that while services or nursing homes were available, there were very few dementia-specific residential care centres. Day-care centres also require that the person with dementia attending their facility should be accompanied at all times by another person at the end of life.

I had put him in a nursing home during his last time; the very next day, they called me and said that they had to throw him out because he was caught with problems. We are putting them here since we aren’t able to manage, or rather, we aren’t sure how to care (PC6, F)

One of the underlying reasons for avoiding day-care centres and nursing homes also seemed to be the perceived futility of their intervention and the unprofessional service of the healthcare staff, especially during the last stage of care. Lack of ambulance or transport services further hindered access to services that required considerable travel and effort:

It’s always a very long waiting time, very long... my dad cannot control his bowels and he gets angry very fast... I tell them (clinic staff), please help me to let him go first... Then my dad starts to get angry, very angry, and that’s when everybody starts to look at us... when my dad finally throws a tantrum, then they let my dad go first. I want a hospital to be more understanding of dementia patients, and reduce our waiting time (PC5, M)

Resources and referral

Caregivers unanimously expressed a strong desire for information about community resources for the patient and caregiver self-care. With respect to the resources needed to care, caregivers frequently expressed the need for patients to socialise. Caregivers felt that it was particularly important for people with dementia to have the opportunity to socialise with someone other than their caregivers:

She probably also needs outside socialisation outside of us! (PC6, F)

Assistance with daily activities

Many caregivers put forward the idea that those who cannot handle the daily living activities themselves may have to move to assisted living or move in with other family members during the last stage of the disease. Independence is gradually lost, and caregivers must provide consistent direct care with most of the ADLs. At this stage, patients must be directly assisted with basic daily living activities such as eating, bathing, transfers and walking.

She has become like a small kid as the days go by. But she is not a child physically. Hence, helping her in daily activities wasn’t easy. Some sort of assistance is needed (PC8, F)

Home and personal safety

Caregivers highlighted that safety issues and wandering would require constant monitoring till the end of life, though the nature of the issues might vary. As the condition progressed, balance and safety awareness declined, requiring significant direct help with transfers and mobility. The home environment could then turn out to be a potential safety hazard. Slippery floors caused by water in the bathroom, lack of handrails in the toilet to aid mobility and inadequate room lighting contributed to fall risk. Addressing home and personal safety for these patients is indeed a critical unmet need.

The weather in the south is very humid. When it comes to the wet season, the floor is very slippery, and old people are prone to falls. (PC1, F)

Support for caregiving

Conflicts in family care: Some caregivers refused to ask family for help, especially in the last stage of the patient, insisting they had ‘enough to do’, while others reported that their request for help was ignored as siblings avoided assuming any caring responsibilities.

… they have their things to worry about, and …none of them have offered to care for her, not even for a weekend (PC8, F)

My brother has washed his hands of my mother and doesn’t want anything to do with this (PC1, F)

The conflict in caregiving is evident as one participant described a sibling who lives abroad and is absent in caregiving, who strongly opposed their mother’s admission to a residential aged care facility in the last stage.

Financial burden

Direct costs of providing care were added to by the loss of income from taking time from (or permanently leaving) paid employment to provide care. Some caregivers experienced severe hardship and were themselves older adults with chronic conditions. This, apart from the chronic illness management, placed a double burden of costs, which impacted access:

I have been on medication for my dialysis- he too…we haven’t been able to afford it. (PC7, F)

Most of the participants stated that they needed more information regarding how to access financial support services. If they had this information, it came from either a family member who worked in a health-related profession or from other sources, such as a bank worker, but not from the treating team. Multiple caregivers reported financial concerns relating to caregiving, medications, hotel stays for clinic visits and general care. The cost of equipment needed for care and the high costs of screening and diagnostic tests have caused numerous challenges.

Symptoms needing better management

Physical symptoms

Profound physical deterioration is a significant feature in end-of-life dementia patients. When queried regarding unaddressed symptoms, caregivers mentioned concerns such as complete loss of speaking ability, pain, bowel and bladder incontinence, nausea and vomiting. Multiple participants mentioned concerns regarding drug reactions and side effects:

I used to find that she used to stay in one position for a long time (such as sitting in a chair) and not move around much. Because of this, she got a scar on her body. Something could have been done to reduce this problem’ (PC4, F)

Psychological symptoms: Caregivers highlighted that these patients have experienced depression, anxiety, restlessness, behavioural problems and aggression in the end-of-life stage. These problems had to be identified and managed to understand and respond to patients’ needs. In this respect, one of the patients’ daughters stated:

If he doesn’t understand why someone is washing or dressing up them, he reacts defensively or with sudden emotional outbursts (PC1, F).

Cultural influences in care

The caregivers explained about the role of cultural factors in the provision of care in the end stage. While the cultural norm of filial piety continues to guide caregiving, stigma remains high. There is a feeling of shame due to the patient’s abnormal behaviours as well as others’ judgements on attributing this to mental disorders. In this respect, one of the caregivers stated:

Others’ behaviour is what makes us sad. Many of my relatives said that it was very hard and asked us how we took care of the issue and how we tolerated her. Shouldn’t we tolerate her? She is our mother; she has done everything for us for a lifetime. Now, it’s our duty. (PC8, F)

Future planning

Caregivers were aware of a missed opportunity to care better for their relatives if they had known better and planned better. Many of them went with the caregiving needs as they happened, without planning for advanced care.

Advanced care planning

Regarding advance care planning and end-of-life discussion, participant comments ranged from doctors who avoided end-of-life discussions and comments about their fear of death and their expectations. These aspects were never discussed or met in the last stage.

‘------- the doctor gave me a brochure ‘What to do when someone dies’ (PC3, M)

‘I didn’t want to know. I couldn’t face thinking about him choking or struggling for breath. But after he passed away, I felt, if I had known about the end of care preparation, it would have felt dignified’ (PC7, F)

DISCUSSION

Our study highlights how caring for individuals with dementia during the advanced stages presents a unique set of challenges that are often unmet for caregivers. As dementia progresses, the physical, emotional and cognitive decline can be overwhelming, requiring caregivers to navigate complex decisions and emotions, making it difficult for caregivers to accurately ascertain the needs of the person with dementia. This uncertainty affects how preferences and priorities are discussed, by whom and when and whose opinions carry the most weight.[23] In the absence of advance care planning, there can be an imbalance between the individual’s perspective, the system of care they are in (for example, a nursing home) and wider systems that provide end-of-life care.[24]

Unpreparedness for end-of-life care among the family caregivers of people with dementia is the core theme which stems from the current study. The absence of formal mechanisms to facilitate these discussions can lead to increased uncertainty and stress for caregivers, who may not have the resources or support to make informed decisions about advanced care.[25] In India, where palliative care services are still developing, caregivers struggle to find appropriate support, leading to gaps in care that can significantly impact the quality of life for both patients and caregivers. The lack of trained professionals and resources in these settings further exacerbates these challenges.[26]

Caregiving is rarely perceived as a separate role from other familial obligations. This expectation, often of gendered caregiving, can lead to significant emotional and physical strain, as caregivers are often left to manage the demands of caregiving with little to no formal support or skills. The findings of this study align with previous research that has highlighted the burdensome nature of caregiving in India, where the lack of formal support systems places an even greater burden on families.[27,28]

A significant observation in dementia caregiving is the overwhelming preponderance of female caregivers even though individuals with dementia are often from both genders and predominantly male. This gendered distribution of caregiving responsibilities is well-documented, with studies indicating that women are more likely to assume caregiving roles due to traditional family expectations, societal norms and perceived emotional readiness.[29]

The ageing status of caregivers themselves is a crucial but frequently disregarded component of caregiving for patients with severe dementia. Elderly children or spouses who are also managing their health issues while providing care make up a large number of primary caregivers. According to studies, the demands of dementia care combined with the difficulties of their age-related diseases frequently result in greater physical and mental health burdens for caregivers over 60.[30] The current study demographics also align with these findings.

Beyond just physical stress, older persons who provide care experience increased rates of anxiety, depression and chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.[31] Furthermore, because intergenerational caregiving support is limited in nuclear family arrangements, many elder caregivers lack extra support. Maintaining successful caregiving and enhancing outcomes for patients and their elderly caregivers requires incorporating caregiver well-being into dementia care programmes.

The participants highlighted the need for specialised home-based care support as the symptoms progress. The three most frequently addressed advanced care domains in the studies reviewed (optimal symptom management, continuity of care and psychosocial support) reflect clinician priorities and the core values of palliative care, irrespective of the reason for dying.[31] There is limited evidence regarding society-based home care services for supporting patients with dementia. Home care services are demonstrated to be accompanied by desirable outcomes when they are provided on time and are responsive, flexible and appropriate to individual needs. Home care services in India are limited, and when available, they are often not responsive or flexible enough to address the unique needs of dementia patients and their caregivers. The lack of trained home care professionals, coupled with financial constraints, means that many families do not receive the support they need, leading to suboptimal outcomes. The development of society-based home care services that are affordable, accessible and culturally appropriate is crucial in addressing this gap in lower- and middle-income countries.[32] A good death with dementia is being pain-free and being surrounded by those closest to the person with dementia; these are not unachievable or particularly technical goals, but necessitate effective communication, cooperation and coordination by health professionals from the early diagnosis.[33] The increasing number of people who will require care as they die with dementia will mean that service models to improve care must be adopted and implemented carefully, considering the variety of settings in which people with dementia die, as well as cultural, staff and organisation with due consideration to what may work best for whom and in what circumstances.[34]

While the study has brought out several valuable insights for practice, certain limitations need to be acknowledged. The study adopted a qualitative approach to gain insight into the caregivers’ needs in advanced dementia. The interview schedule was more focused, and the data analysis was thematic, which led to the descriptions of the caregiver’s unmet needs. In this process, the nuances of meaning and experiences were not the focus of the study. As the participants were bereaved caregivers reflecting on past experiences, there may be inaccuracies or selective recollection of events and unmet needs (potential recall bias)

CONCLUSION

The study highlights the need to recognise the eventual terminal nature of dementia, anticipate specific needs that will change over time throughout the disease trajectory, and that a palliative care approach is adopted, irrespective of the type or stage of dementia. Middle-income countries are home to 70% of the world’s population, and the demographic changes are more acutely felt in this context. Recognising the challenges faced by caregivers and providing targeted support not only enhances the quality of care for individuals with dementia but also acknowledges the crucial role caregivers play in facilitating a dignified and compassionate end-of-life experience. As society continues to struggle with the impact of dementia, fostering an environment that supports caregivers in meeting these needs becomes increasingly imperative.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the entire neuropalliative care team in the institute and the caregivers who shared their insights with us.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), number No. NIMHANS/28th IEC (BS & NS DIV.)/2021, dated 23rd June 2021.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Positive Experiences of Caregiving in Family Caregivers of Older Adults with Dementia: A Content Analysis Study. Iran South Med J. 2018;4:319-34.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Expert Group on Socio-Economic Caste Survey Ministry of Rural Development New Delhi.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of DSM-5 Mild and Major Neurocognitive Disorder in India: Results from the LASI-DAD. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0297220.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Dementia in India: National and State Estimates from a Nationwide Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:2898-912.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challenges for Lower-Middle-Income Countries in Achieving Universal Healthcare: An Indian Perspective. Cureus. 2023;15:e33751.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding Caregiver Burden and Quality of Life in Kerala's Primary Palliative Care Program: A Mixed Methods Study from Caregivers and Providers' Perspectives. Int J Equity Health. 2024;23:92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Asian Immigrants' and their Family Carers' Beliefs, Practices and Experiences of Childhood Long-Term Conditions: An Integrative Review. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78:1897-908.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priorities and Preferences of People Living with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment-A Systematic Review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:2793-807.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care in Iran: Moving Toward the Development of Palliative Care for Cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:240-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Living with and Caring for Patients with Alzheimer's Disease in Nursing Homes. J Caring Sci. 2013;2:187-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Time to Live and a Time to Die: Palliative Care in Dementia. Nurs Resid Care. 2009;11:399-401.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and their Carers United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Appropriation and Dementia in India. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2011;35:501-18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adverse Consequences of Unmet Needs for Care in High-Need/High-Cost Older Adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75:459-470.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unmet Needs of Community-Residing Persons with Dementia and their Informal Caregivers: Findings from the Maximizing Independence at Home Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2087-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unmet Needs of Caregivers of Individuals Referred to a Dementia Care Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:282-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Which Unmet Needs Contribute to Behavior Problems in Persons with Advanced Dementia? Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:59-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Why We Don't Need “Unmet Needs”! on the Concepts of Unmet Need and Severity in Health-Care Priority Setting. Health Care Anal. 2019;27:26-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Met and Unmet Care Needs of Older People with Dementia Living at Home: Personal and Informal Carers' Perspectives. Dementia. 2019;18:1963-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Dementia Subtypes in United States Medicare Fee-for-service Beneficiaries, 2011-2013. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:28-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A System Lifeworld Perspective on Dying in Long Term Care Settings for Older People: Contested States in Contested Places. Health Place. 2011;17:263-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental and Physical Illness in Caregivers: Results from an English National Survey Sample. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:197-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care Need in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Indian J Palliat Care. 2023;29:375-87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systems Perspective: Understanding Care Giving of the Elderly in India. Health Care Women Int. 2009;30:1040-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between Physical Activity and Cognitive Functioning among Older Indian Adults. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2725.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gender Differences in Caregiver Stressors, Social Resources, and Health: An Updated Meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:P33-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental and Physical Illness in Caregivers: Results from an English National Survey Sample. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:197-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 14]

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence of what Works to Support and Sustain Care at Home for People with Dementia: A Literature Review with a Systematic Approach. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:59.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home Care Program and Exercise Prescription for Improving Quality of Life in Geriatric Population with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Bodywork Move Ther. 2024;40:1645-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]