Translate this page into:

Assessment of Palliative Care Needs among People Living with HIV/ AIDS Attending Antiretroviral Therapy Outpatient Department in an Urban Slum of Mumbai: A Mixed Method Study

*Corresponding author: Prabhadevi Ravichandran, Department of Community Medicine, Seth G.S. Medical College and K.E.M Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. deviprabha28@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Lavangare SR, Ravichandran P. Assessment of Palliative Care Needs among People Living with HIV/AIDS Attending Antiretroviral Therapy Outpatient Department in an Urban Slum of Mumbai: A Mixed Method Study. Indian J Palliat Care 2022;28:43-50.

Abstract

Objectives:

According to WHO, Palliative care is an essential component of a comprehensive package of care for people living with HIV/AIDS. Lack of palliative care results in untreated symptoms that hamper an individual’s ability to perform daily activities. The study aimed to explore the perceived Palliative care needs of People Living With HIV/AIDS and the association between socio- demographic profile with Palliative care needs.

Materials and Methods:

It was a mixed method study conducted over 2 months in November and December 2020 at Link ART OPD of Urban Health Training Centre in Mumbai. Out of 120 registered patients,15 patients were selected for in-depth interview by purposive sampling. The remaining 105 patients were selected for quantitative part of the study by complete enumeration method. For Qualitative part, Thematic analysis of the transcripts was done. Data were coded using Microsoft word comment feature. Themes and categories were drawn from it. For Quantitative part, Data analysis was done using SPSS version 22. Chi- square test was applied to find out the association between socio- demographic profile & palliative care needs. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The major themes identified were poor attitude towards the disease, lack of support and role of counselling. The common palliative care needs identified were need for financial assistance, family support and psychological support.

Conclusions:

Palliative care should be introduced early in the care process by a team of providers who is aware of the patient’s history and requirements.

Keywords

Attitude

Counselling

Palliative care

Stigma

INTRODUCTION

One of the limitations in curative medicine is the inability to improve the quality of life of patients suffering from chronic diseases.[1] In such conditions, palliative care plays an important role. It is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.[2]

As per the Global Atlas of Palliative care, the common conditions among adults which require palliative care are cardiovascular diseases (38.5%), cancer (34%), chronic respiratory diseases (10.3%), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (5.7%), diabetes (4.5%), kidney diseases (2%), cirrhosis (1.7%) and Alzheimer’s (1.65%).[3] Globally, around 2.7 million people are living with HIV and about 1.89 million suffer from pain requiring palliative care.[4]

For effective planning and implementation of palliative care for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), identification of their needs is important. There are very few studies in India which explored the palliative care needs of this group of patients. The prevalence of HIV/AIDS in urban slum dwellings in India is also high. Hence, this study was conducted with the following objectives.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to:

Describe the patient’s experiences of living with HIV through semi-structured in-depth interviews

Assess their perceived palliative care needs through a semi-structured questionnaire adapted from the literature

Find the association between sociodemographic profile with their palliative care needs

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It was a mixed method study conducted over a period of 2 months between November 2020 and December 2020 at the link antiretroviral therapy outpatient department (ART OPD) of Urban Health Training Centre attached to a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai. This link ART OPD serves mainly for urban slum population. All the HIV/AIDS patients who were registered were included in the study.

Qualitative part – to study the patient’s experiences of living with HIV

The grounded theory approach was used in the qualitative part of the study. Out of 120 PLWHA registered at link ART OPD, 15 of them were selected for in-depth interview by purposive sampling. After explaining the purpose of the study and getting written informed consent, in-depth interview was conducted for individual patients by maintaining privacy and confidentiality. The interview was related to experiences of living with HIV. Thematic analysis of the transcripts was done. Data were coded using Microsoft Word comment feature. A predominant inductive approach was used to code the transcripts. Themes and categories were drawn from it.

Quantitative part – to study the palliative care needs

The remaining 105 patients were selected for the quantitative part of the study by the complete enumeration method. After explaining the purpose of the study and getting written informed consent, face-to-face interview was conducted on the 105 PLWHA using a pre-designed, pre-tested, semi-structured interview schedule. The interview schedule has been adapted from similar literature.[5] Questions were asked regarding their sociodemographic profile, symptomatology, comorbidities, activities of daily living (ADL), and palliative care needs. Data were entered into MS Excel 2010 and were analysed using SPSS version 22 software. Test of significance (Chi-square test) was applied to find out the association between sociodemographic profile and palliative care needs. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The data from the inferential stage/phase are integrated. The themes and subthemes from the qualitative component are integrated with the results of the quantitative component (palliative care needs) by concurrent triangulation process. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (EC/OA-154/2019) on 31 October 2020.

RESULTS

Qualitative part – to study the patient’s experiences of living with HIV

Among 15 patients who were purposively selected for in-depth interviews, seven were below 45 years and eight were above 45 years. These 15 patients belonged to different domains such as migrants, commercial sex worker, illiterate, widow, drug addict, unmarried, and transgender. These domains were represented equally in both age groups. The demographic pro forma and disease characteristics of these 15 participants are given in [Table 1].

| S. No. | Sociodemographic profile | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age (in years) | ||

| Below 45 | 7 | 46.7 | |

| Above 45 | 8 | 53.3 | |

| 2 | Sex | ||

| Male | 7 | 46.7 | |

| Female | 6 | 40 | |

| Transgender | 2 | 13.3 | |

| 3 | Education | ||

| Graduate | 1 | 6.7 | |

| Intermediate/diploma | 1 | 6.7 | |

| High school | 4 | 26.7 | |

| Middle school | 7 | 46.7 | |

| Illiterate | 2 | 13.3 | |

| 4 | Occupation | ||

| Clerical, farmer and shop owner | 1 | 6.7 | |

| Skilled work | 8 | 53.3 | |

| Unskilled work | 2 | 13.3 | |

| Unemployed | 4 | 26.7 | |

| 5 | Socioeconomic status | ||

| Middle class | 2 | 13.3 | |

| Lower-middle class | 10 | 66.7 | |

| Lower class | 3 | 20 | |

| 6 | Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 2 | 13.3 | |

| Married | 10 | 66.7 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 6.7 | |

| Widowed | 2 | 13.3 | |

| 7 | Number of years living with HIV (years) | ||

| <5 | 4 | 26.7 | |

| 5–10 | 7 | 46.7 | |

| >10 | 4 | 26.7 | |

| 8 | WHO HIV stage (n=15) | ||

| Stage 1 | 8 | 53.3 | |

| Stage 2 | 3 | 20 | |

| Stage 3 | 2 | 13.3 | |

| Stage 4 | 2 | 13.3 |

The transcripts lead to the development of codes, categories, and themes which are illustrated [Figure 1].

- Thematic analysis of in-depth interviews.

Theme 1: Poor attitude toward the disease

During the in-depth interview, the participants shared various discriminatory attitudes experienced by them. They discussed in detail about the fear of disclosing the truth to their family members. However, their health-seeking behaviour was not affected by these issues. Three major categories drawn from the in-depth interviews are explained [Table 2].

| Category 1: Social stigma/rejection | |

|---|---|

| Description | Verbatim |

| Stigma is a feature of HIV disease and many people have reported that their lives are affected by discrimination and rejection. In our study, even participant’s own family members showed discrimination. | ‘I usually cover my face while coming here to get my medicines because of societal stigma.’ (a 47-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) |

| ‘My family members do not even allow me to cut vegetables.’(a 59-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) | |

| ‘We are living alone as we do not want to disturb our family members.’(a 34-year-old male, HIV-positive patient) | |

| Category 2: Fear of disclosure | |

| Description | Verbatim |

| Disclosing the HIV status to close family members has number of advantages. However, our participants felt shame and embarrassment to reveal the disease to their family members. They have tried to hide their medicines by removing the label of the medicine container | ‘I come here quietly, I keep ART card in my shirt pocket whenever I come here to get medicines, so that no one knows I am having the disease.’ (a 40-year-old male, HIV-positive patient) |

| ‘I remove the stickers pasted outside the medicine container, then one day my wife found it.’ (a 40-year-old male, HIV-positive patient) | |

| ‘I go for work in a building, security checks our bag always, so I tear the label pasted outside the medicine container, so that no one knows I am taking these drugs.’(a 28-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) | |

| Category 3: Health-seeking behaviour | |

| Description | Verbatim |

| Participants wanted counselling services, treatment services and medication services from one fixed place rather than juggling between different places. Some participants mentioned that they get encouraged by visiting religious places which improve their sense of well-being. People did not want home-based care as it might reveal their HIV status to family and neighbours | ‘In my house, first no one spoke to me for few days, If I do not come to hospital, I know I will die.’ (a 35-year-old male, HIV-positive patient) |

| ‘Initially I felt very difficult, I went to different doctors, they changed many drugs.’ (a 51-year-old male, HIV-positive patient) | |

| ‘I do not want home-based care, as the neighbours will think bad.’ (a 38-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) | |

| ‘Whenever I go to church, my pain goes away.(a 46-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) |

Theme 2: Lack of support

Respondents highlighted the importance of having family support in this theme. Most of them showed worry and anxiety due to a lack of support from family and government. Three major categories drawn from the in-depth interviews are explained [Table 3].

| Category 1: Lack of family support | |

|---|---|

| Description | Verbatim |

| To share their experiences, difficulties and needs, getting family support is very important. We got mixed reactions from our participants. The most of them told they did not get any meaningful support from their family. However, few of them told their young children take care of them | ‘I know about the financial help given by bank, but my mother-in-law does not give me ration card to avail the services.’ (a 38-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) ‘No one is supportive, I am supporting everyone.’ (a 47-year-old male, HIV-positive patient) ‘My daughter got job as airhostess, she told me to stay at home, my daughter will work and support me.’ (a 37-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) ‘My children keep alarm to remind me to take tablets, they call me to confirm whether I had taken the tablet or not.’ (a 46-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) |

| Category 2: Lack of monetary support | |

| Description | Verbatim |

| Participants mentioned the need for money to pay school fees of children, buy groceries, buy medications, etc., Participants highlighted the need for proper nutritional intake during the course of the disease and treatment. However, both money and nutrition were a dream to many of our participants. | ‘I do not know how me and my husband got the disease. We have three girl children; we think of going for extra job.’ (a 39-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) ‘We do not have money to buy even milk, we are living in rent, we cannot buy nutritious food also, we know the NGO proving nutritional support, but it is far from our place.’ (a 37-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) |

| Category 3: Lack of government support | |

| Description | Verbatim |

| The most of the participants were returned back many times from various government facilities for not having necessary documents for availing the services | ‘Documentations and procedures are more to get financial help from government, it is waste of time.’ (a 40-year-old male, HIV-positive patient) |

Theme 3: Role of counselling

Counselling an individual with HIV infection is important because HIV infection is lifelong illness and to address the anxiety, denial, anger and guilt experienced by patients. Two major categories drawn from the in-depth interviews are mental health issues and health education.

Mental health issues

Issues such as depression, loneliness and addictions experienced by our patients have been addressed well by the counsellors who have improved their quality of life.

‘I was depressed at beginning, I wanted to tell my story to someone, counselling helped me a lot.’ (a 40-year-old male, HIV-positive patient)

‘I feel bad whenever I am not able to go to work due to disease.’ (a 50-year-old female, HIV-positive patient) ‘I took tobacco, gutka and alcohol, I got TB with HIV. Counsellor told if I didn’t stop all these addictions, medicines won’t work.’ (a 49-year-old male, HIV-positive patient)

Health education

Many participants highlighted the need for counselling and health education for family members and society to reduce the stigma associated with HIV.

‘I used to get tablet for 3 months at a time; I come to ART OPD less frequently, because of relatives. Counselling has to be given to family members who think bad about the disease.’ (a 38-year-old female, HIV-positive patient)

Quantitative part – to study the palliative care needs

The sociodemographic characteristics of the 105 PLWHA who were selected for the quantitative part of the study are presented [Table 4]. The mean age of PLWHA was 38 years. Nearly 20 (19%) PLWHA reported body ache as their predominant symptom followed by weakness n = 5 (4.8%), weight loss n = 5 (4.8%), skin disease n = 4 (3.8%), tingling and numbness n = 4 (3.8%), gastritis n = 4 (3.8%), upper respiratory tract infection n = 3 (2.8%), generalised itching n = 2 (1.9%) and 1% each is constituted by Candida white discharge per vagina, burning micturition, loss of appetite, menstrual problem and excessive sleepiness. Almost half of PLWHA 53 (50.5%) had no symptoms. Ten out of 105 PLWHA (9.5%) were found to have difficulty in performing ADL. We found that the association between presenting symptoms and difficulty in performing ADL was highly significant (χ2 = 38.8, P= 0.000). Those who were suffering from body ache had more difficulty in performing ADL than others.

| S. No. | Sociodemographic profile | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age (in years) | ||

| 20–30 | 13 | 12.4 | |

| 30–40 | 41 | 39.0 | |

| 40–50 | 32 | 30.5 | |

| >50 | 19 | 18.1 | |

| 2 | Sex | ||

| Male | 43 | 41.0 | |

| Female | 57 | 54.3 | |

| Transgender | 5 | 4.8 | |

| 3 | Education | ||

| Graduate | 2 | 1.9 | |

| Intermediate/diploma | 4 | 3.8 | |

| High school | 22 | 21.0 | |

| Middle school | 51 | 48.6 | |

| Illiterate | 26 | 24.8 | |

| 4 | Occupation | ||

| Professional | 2 | 1.9 | |

| Clerical, farmer and shop owner | 8 | 7.6 | |

| Skilled work | 41 | 39.0 | |

| Unskilled work | 18 | 17.1 | |

| Unemployed | 36 | 34.3 | |

| 5 | Socioeconomic status | ||

| Upper class | 4 | 3.8 | |

| Upper-middle class | 11 | 10.5 | |

| Middle class | 39 | 37.1 | |

| Lower-middle class | 44 | 41.9 | |

| Lower class | 7 | 6.7 | |

| 6 | Marital status (n=100 after excluding transgenders) | ||

| Unmarried | 3 | 3 | |

| Married | 81 | 81 | |

| Divorced | 7 | 7 | |

| Widowed | 9 | 9 | |

| 7 | Number of children (n=97 after excluding unmarried persons) | ||

| No children | 6 | 6.2 | |

| 1–2 children | 59 | 60.8 | |

| >2 children | 32 | 33.0 | |

| 8 | Number of years living with HIV (year) | ||

| <5 | 41 | 39.0 | |

| 5–10 | 32 | 30.5 | |

| >10 | 32 | 30.5 | |

| Total | 105 | 100.0 | |

| 9 | WHO HIV stage | ||

| Stage 1 | 80 | 76.2 | |

| Stage 2 | 15 | 14.3 | |

| Stage 3 | 7 | 6.7 | |

| Stage 4 | 3 | 2.9 | |

The palliative care needs identified by PLWHA are illustrated [Figure 2]. The majority of PLWHA identified the need for financial assistance. Out of 50 (47.6%) PLWHA who required financial assistance, only 11 (22%) of them received it so far. The second most frequently identified need reported by 38 (36.2%) PLWHA who were a need of family support. The need for psychological support was reported as the third greatest need by 37 (35.2%) PLWHA.

- Palliative care needs.

We can see from [Table 5] that there is a significant association between gender with financial needs (χ2 = 7.6, P = 0.019) and nutritional needs (χ2 = 7.7, P = 0.010). The need was high among females who run the households and take care of their husbands and children. There was a significant association between the number of family members in house with psychological support (χ2 = 6.7, P = 0.009). It was found that participants who were living alone with their spouse or with children were in more need of psychological support. To overcome the stress due to loneliness, participants would like to talk to someone and share their feelings. The association between the number of years living with HIV and the need for psychological support was highly significant (χ2 = 13.3, P = 0.001). It is seen from that table, those PLWHA for <5 years were in more need of psychological support than others. This might be because they are recently diagnosed, they might take time to accept the disease and live to the fullest.

| S. No. | Sociodemographic profile | Palliative care needs | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender | Financial needs (%) | ||

| Yes | No | |||

| Male | 15 (34.9) | 28 (65.1) | χ2=7.632, d.f.=2 Fisher’s exact value, P=0.019 |

|

| Female | 34 (59.6) | 23 (40.4) | ||

| Transgender | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| Total | 50 (47.6) | 55 (52.4) | ||

| 2 | Gender | Nutritional needs (%) | ||

| Yes | No | |||

| Male | 8 (18.6) | 35 (81.4) | χ2=7.770, d.f.=2 Fisher’s exact value, P=0.019 |

|

| Female | 23 (40.4) | 34 (59.6) | ||

| Transgender | 0 (0) | 5 (100.0) | ||

| Total | 31 (29.5) | 74 (70.5) | ||

| 3 | Number of family members | Psychological support (%) | ||

| Yes | No | |||

| 2–3 members | 13 (44.8) | 16 (55.2) | χ2=6.757, d.f.=1 Chi-square value, P=0.009 |

|

| >4 members | 15 (19.7) | 61 (80.3) | ||

| Total | 28 (26.7) | 77 (73.3) | ||

| 4 | Number of years living with HIV (years) | Psychological support (%) | ||

| Yes | No | |||

| <5 | 19 (46.3) | 22 (53.7) | χ2=13.395, d.f.=2 Chi-square value, P=0.001 |

|

| 5–10 | 5 (15.6) | 27 (84.4) | ||

| >10 | 4 (12.5) | 28 (87.5) | ||

| Total | 28 (26.7) | 77 (73.3) | ||

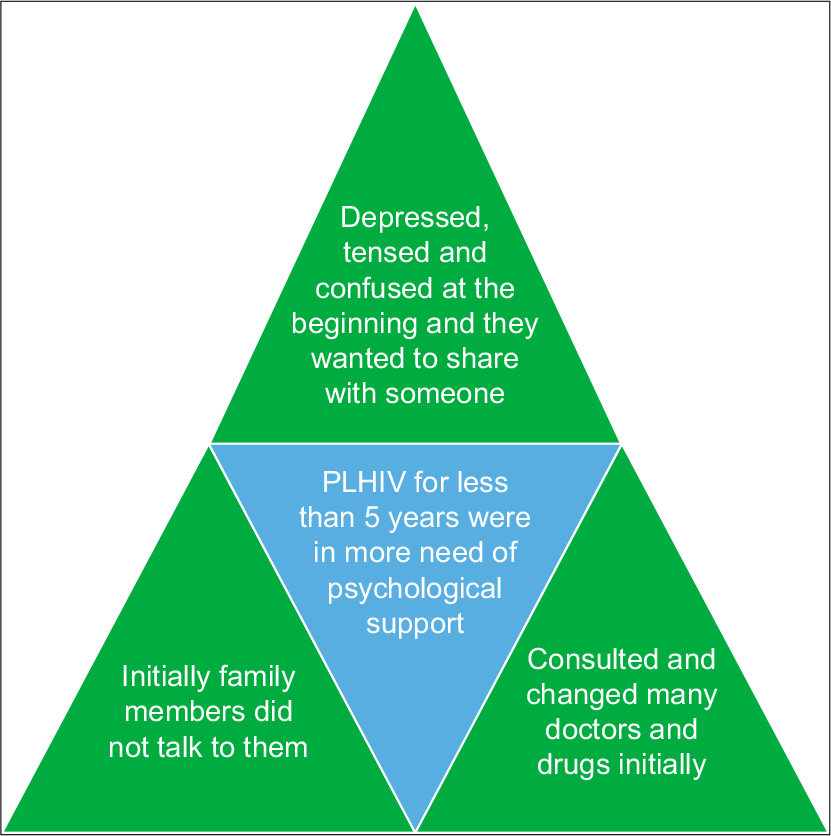

The triangulation between quantitative and qualitative findings which support each other is given in [Figures 3 and 4]. The operational definition for various palliative care needs is given in [Table 6].

| S. No. | Palliative care needs | Operational definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Financial needs | Financial assistance to the patients and their family members to meet their basic needs such as food, rent, purchase of drugs and school fees of children.[5] |

| 2 | Nutritional needs | Nutritional support like monthly ration to help patients live as actively as possible and prevent nutritional deficiencies |

| 3 | Psychological support | Assessing if the family is physically and emotionally capable of caring for the patient and offering education along with counselling to the patient as well as family members |

| 4 | Spiritual support | To understand the meaning of life and improvement in belief and faith |

| 5 | Healthcare needs | To draw an experience and communication between patient and healthcare provider to provide best combination of intervention and medications |

- Triangulation between quantitative and qualitative findings.

- Triangulation between quantitative and qualitative findings.

DISCUSSION

The in-depth interviews conducted among 15 participants with HIV revealed that they faced social, psychological, and family problems while living with the disease. Some of the categories which emerged in this interview were social stigma, fear of disclosure, health issues, lack of family, monetary and government support. These findings were consistent with the similar study conducted by Dejman et al. in Iraq where almost similar types of findings were found.[6]

The quantitative part of the study explored the palliative care needs of PLWHA. About 52 (49.5%) PLWHA reported experiencing symptoms and among these 52 people, 20 (19%) were suffering from body ache. The association between reported symptoms and difficulty in performing ADL was found to be highly significant (P = 0.000). The results were consistent with the similar study conducted by Uwimana in Rwanda in which about 92% of PLWHA had physical symptoms, and the association between reported health status and the ability to perform ADL was also found to be significant (P < 0.001).[7]

Our study results show that PLWHA were in need of financial assistance; family support; psychological support; nutritional support; care for their children; pain relief; spiritual support and change in the healthcare system. The necessities identified in our study were almost the same as the results of similar studies such as Uwimana, Laschinger et al. and Sepulveda et al. The four commonly identified palliative care needs are briefed below.[7-9]

The most frequently identified palliative care need reported by 50 (47.6%) PLWHA who were financial assistance. This is consistent with the results of a similar study conducted by Ekiria Kikule in Uganda where 71 of 173 (30%) study participants were experiencing financial problems and required financial support.[5] The triangulation of findings in our study suggests that poor housewives, widows, difficulties in child rearing, lack of family support, lack of government widow pension, etc., contribute to the association between female genders with the increased need for financial support [Figure 3]. The findings were similar to the study conducted by Kaba et al. in Ethiopia where female PLWHA complained that the palliative care support they received was not sufficient and they needed more economical support that will help them to recover fully and support their children.[10] The results were also similar to the study conducted by Selman et al. in Sub-Saharan Africa where the females worried for a lack of enough food, lack of money for transportation to collect medicines, and children’s education.[11]

The second prerequisite reported by 38 (36.2%) PLWHA who were family support. Although few of the family members had knowledge about the disease, they exhibited a bad attitude toward them which worried many participants. Furthermore, care at home was not preferred by the majority of them due to poor family support. The results were in contrast with the similar study by Prasad et al. in Pondicherry where the majority preferred home-based care due to the good family support and to save the time and money in reaching the hospitals.[12]

Family support was followed by the need for psychological support among 37 (35.2%) PLWHA patients. The triangulation of findings in our study suggests that, at the initial stages of diagnosis, patients experienced depression, tension and confusion related to the cause of the disease which resulted in consulting many doctors. They were not able to accept the disease at the beginning. This contributes to the association between PLHIVs for <5 years with the increased need for psychological support [Figure 4]. The results were similar to the findings of the study by Senyurek et al. in Turkey where the participants experienced a sudden emotional trauma on receiving the diagnosis and they were reluctant to acknowledge their diagnosis due to fear of rejection and stigmatisation.[13] The results were in contrast with the similar study conducted by Jameson in South Africa where surprisingly psychological issues were not a big problem possibly because the urgency and severity of the demands of day-to-day survival.[14]

Thirty-one (29.5%) PLWHA wished to get nutritional support. Females and married participants were in more need of nutritional support than others. However, unfortunately, the procedures and documentation required to obtain these services from the government and NGO are more that many people fail to get it. Lack of access to transportation also hinders the ability to obtain these services. The results were consistent with results of a similar study by Mkwinda,and Lekalakala-Mokgele in Malawi where participants highlighted the importance of proper nutrition with all food groups to improve well-being.[15]

CONCLUSION

Addressing these palliative care needs identified in our study help to improve the survival and quality of life of PLWHA. Palliative care should be introduced early (Stages 1 and 2) in the care process by a team of providers who are aware of the patient’s history and requirements. The introduction of palliative care programme to address these issues and provision for integration of the healthcare services at one-stop clinic is the pressing priority now.

Acknowledgement

We authors would like to thank Dr Gajanan D Velhal, Professor and Head of Department of Community Medicine, Seth G.S. Medical College and KEM Hospital for giving us approval for conducting this study. We would also like to thank Additional Project Director of Mumbai District AIDS Control Society, for giving us permission to conduct this study. Last but not the least, we also thank all the participants of this study.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Palliative care for non-cancer patients in tertiary care hospitals. Int J Med Public Health. 2016;6:151-3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care: The World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:91-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/global_atlas_of_palliative_care.pdf [Last accessed on 2019 Dec 03]

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposal of Strategies for Palliative Care in India (Expert Group Report) 2020. Available from: https://www.palliumindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/national-palliative-care-strategy-nov_2012.pdf [Last accessed on 2020 Nov 10]

- [Google Scholar]

- A good death in Uganda: Survey of needs for palliative care for terminally ill people in urban areas. Br Med J. 2003;327:192-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological, social, and familial problems of people living with HIV/AIDS in Iran: A qualitative study. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:126.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Met and unmet palliative care needs of people living with HIV/ AIDS in Rwanda. SAHARA J. 2007;4:575-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health care providers' and patients' perspectives on care in HIV ambulatory clinics across Ontario. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2005;16:37-48.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality care at the end of life in Africa. Br Med J. 2003;327:209-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care needs and preferences of female patients and their caregivers in Ethiopia: A rapid program evaluation in Addis Ababa and Sidama zone. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248738.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- My dreams are shuttered down and it hurts lots-a qualitative study of palliative care needs and their management by HIV outpatient services in Kenya and Uganda. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of need for palliative care among noncancer patients attending a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:403-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lived experiences of people living with HIV: A descriptive qualitative analysis of their perceptions of themselves, their social spheres, healthcare professionals and the challenges they face daily. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The palliative care needs of patients with stage 3 and 4 HIV infection. Indian J Palliat Care. 2008;14:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care needs in Malawi: Care received by people living with HIV. Curationis. 2016;39:1664.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]