Translate this page into:

Exploring Perception of Terminally Ill Cancer Patients about the Quality of Life in Hospice based and Home based Palliative Care: A Mixed Method Study

*Corresponding author: Dhriti Patel, Department of Internal Medicine, B.J. Medical College and Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. dhritipatel35@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Patel D, Patel P, Ramani M, Makadia K. Exploring perception of terminally ill cancer patients about the quality of life in hospice based and home based palliative care: A mixed method study. Indian J Palliat Care 2023;29:57-63.

Abstract

Objectives:

The objectives of the study were to evaluate the perceptions and performance of terminally ill cancer patients regarding the quality of palliative care at different settings and to measure their quality of life (QOL) at the end of life.

Material and Methods:

This comparative, parallel and mixed method study was conducted at the Community Oncology Centre, Ahmedabad, among 68 terminally ill cancer patients as per inclusion criteria; who were receiving hospice (HS)-based and home (HO)-based palliative care under 2 months permitted by the Indian Council of Medical Research. In this parallel and mixed method study, qualitative findings were supplemented by quantitative data with both components executed simultaneously. Interview data were recorded by taking extensive notes during interviews along with an audio recording. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and a thematic approach was adopted. QoL questionnaire (‘FACIT© System’) was used for the assessment of QOL in terms of four dimensions. Data were analysed using the appropriate statistical test on Microsoft Excel.

Results:

The qualitative data (primary component) analysed under five themes – staff behaviour, comfort and peace, enough and consistent care, nutrition and moral support, in the present study favours a HS-based setting more than a HO-based setting. Among all four subscale scores, physical well-being and emotional well-being subscale scores were statistically significantly associated with the place of palliative care. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) total score was high among patients getting HO-based palliative (mean = 67.64) care than HS-based palliative care (mean = 56.56) and the difference between total FACT-G scores was statistically significant (unpaired t-test = 2.20, P = 0.03).

Conclusion:

Overall, with the primary component favouring HS care and higher scores obtained in HO-based patients, the present study advocates the necessity for palliative services to expand their coverage regardless of whether they are provided at HS or HO, as it has improved the QOL of cancer patients significantly.

Keywords

Cancer

Home-based care

Hospice

Palliative care

Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the second leading cause of death globally and is responsible for an estimated 10 million deaths in 2020.[1] Globally, about one in six deaths is due to cancer. Approximately 70% of deaths from cancer occur in low- and middle-income countries.[2] There are estimated 2.5 million people living with cancer in India, with every year about 700,000 new cancer cases registered.[3] The International Agency for Research on Cancer GLOBOCAN project has predicted that India’s cancer burden will nearly double in the next 20 years, from slightly over a million new cases in 2012 to more than 1.7 million by 2035.[4]

It is estimated that over 40 million people require palliative care each year out of which over 20 million require palliative care near the end of life (EOL).[5] It is estimated that in India, the total number of people who need palliative care is likely to be 5.4 million people a year.[6] Although palliative care services have been in existence for many years, India ranks at the bottom of the Quality of Death Index in overall score and lacks the awareness and existence of hospice (HS) care. According to the Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance, although >100 million people across the world would benefit from HS and palliative care annually.[7]

Thus, it is important that patients with cancer are educated about their options for care at the EOL, which can be provided in different settings such as HS and even at patients’ home (HO).[8,9] However, less research has focused on defining quality EOL care when the patient is at HO or HS. HS provides palliative and supportive care to patients at the EOL through an interdisciplinary team of providers who address the physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs of patients and their families.[10] It is aimed to ‘Add life to days and not days to life’ of cancer patients in advanced stages. It is, therefore, important to understand the potential preferences of terminally ill cancer patients in improving quality of life (QOL) in different healthcare settings, particularly HS-based and HO-based palliative care.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This comparative study was conducted at the Community Oncology Centre among 68 terminally ill cancer patients who were receiving HS-based and HO-based palliative care for 2 months permitted by the Indian Council of Medical Research. In this parallel and mixed method study, qualitative data were the primary component and quantitative data were the secondary component with both components executed simultaneously.

The study permission was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee before commencing the study. Before each interview, patients were explained the purpose of these questions and their participation was requested with written consent. Assurance for confidentiality was given. The study was restricted to patients being 18 years of age or over, with a diagnosis of being in a terminal stage of cancer and having no difficulty with communication. Paediatric patients, cognitively impaired, clinically depressed/ withdrawn or those denying to give consent were excluded from the study.

Interview data were recorded by taking extensive notes during interviews along with an audio recording taken in Hindi language. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and a thematic approach was adopted to analyse the qualitative data findings. The interviews, transcription, translation and thematic analysis were performed independently by the principal investigators (Patel D. and Patel P.), each following the six steps proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006).[11] Both are proficient in Hindi and English. In Step 1, data familiarisation was achieved through a repetitive reading of all transcripts. In Step 2, relevant data were organised into meaningful codes. In Step 3, codes were classified into potential themes. They were then carefully reviewed in Step 4. Step 5 involved naming and clearly defining the themes. In Step 6, the report was written with the support of a literature review. The researchers compared their initial analyses and agreed on theme definitions and a common thematic structure. In case of any discrepancy, a third author was asked to review the themes and codes (Makadia K.). The codes and themes were reviewed by other authors before reporting.

Cella et al. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, Version 4 (FACT-G v. 4), a questionnaire available in Hindi language was used for the assessment of the QOL.[12,13] In an attempt to quantify QOL, many scales have been devised, revised and adapted over the years including the University of Wisconsin – QOL, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL Quotient-C30 and McGill QOL; however, for this study, the FACT-G questionnaire was preferred for its simple language and easy scoring system. It is comprised of four subscales: Physical well-being (PWB; 7 items, score range 0–28), social/family well-being (SWB; 7 items, score range 0–28), emotional well-being (EWB; 6 items, score range 0–24) and functional well-being (FWB; 7 items, score range 0–28). All items in FACT-G use a 5-point rating scale (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit; 2 = somewhat; 3 = quite a bit and 4 = very much). The FACT-G total score is computed as the sum of the four subscale scores, provided that the overall item response is at least 80% (i.e., at least 22 of the 27 items were answered) and has a possible score range of 0–108 points. Higher subscale and total score indicate better QoL. Questionnaire data were entered and analysed using an appropriate statistical test on Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

The present study was conducted at Community Oncology Centre. Around 38% of the cancer patients belonged to the 40–50 years of age group. Sixty-five patients (95%) were married. About 47% of the cancer patients (n = 32) had primary education, 29% had secondary education (n = 20) and about 16% of them were illiterate (n = 11). Around 49% of the participants (n = 33) belonged to a joint family. Among the 68 patients, around 75% of the cancer patients had a positive history of addiction such as smokeless tobacco consumption (51%), smoking (22%) and alcohol consumption (1.47%). According to the modified Prasad classification, the majority of the beneficiaries belonged to socioeconomic Class 5 (61.8%). Other sociodemographic characteristics are shown in [Table 1].

| Characteristics | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <40 | 13 | 19.1 |

| 40–50 | 26 | 38.2 |

| 50–60 | 13 | 19.1 |

| 60–70 | 12 | 17.6 |

| >70 | 4 | 5.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 44 | 64.7 |

| Female | 24 | 35.3 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 11 | 16.2 |

| Primary | 32 | 47.1 |

| Secondary and higher secondary | 20 | 29.4 |

| Graduate and postgraduate | 5 | 7.4 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 55 | 80.9 |

| Muslim | 13 | 19.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 65 | 95.6 |

| Unmarried | 3 | 4.4 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Class 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Class 2 | 2 | 2.9 |

| Class 3 | 6 | 8.8 |

| Class 4 | 18 | 26.5 |

| Class 5 | 42 | 61.8 |

| Types of family | ||

| Nuclear | 25 | 36.8 |

| Joint | 33 | 48.5 |

| Extended | 10 | 14.7 |

| Type of addiction | ||

| Smokeless tobacco | 35 | 51.47 |

| No history of addiction | 17 | 25 |

| Smoking | 15 | 22.06 |

| Alcohol | 1 | 1.47 |

[Figure 1] shows that the majority (44.1%) of the cancer patients had oral cancer. Among them, 22 (73.33%) were male and 8 (26.67%) were female. Around 29% of females had breast cancer among all the female study participants. There was almost equal participation from both HS- (51%) and HO-based (49%) palliative care receiving participants. The provision of palliative care services at either setting resulted in a better performance in the domain of social and emotional dimensions while the participants had an average performance in the physical and functional well-being dimensions, as shown in [Table 2].

- Distribution of study participants according to the type of cancer.

| Subscale scores | Maximum score | Minimum score | Mean score | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWB | 27 | 1 | 13.16 | 5.96 |

| SWB | 28 | 0 | 19.36 | 8.88 |

| EWB | 24 | 1 | 15.82 | 6.31 |

| FWB | 28 | 3 | 13.18 | 6.32 |

| FACT-G total score | 105 | 17 | 61.94 | 21.35 |

QOL: Quality of life, FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, PWB: Physical well-being, SWB: Social well-being, EWB: Emotional well-being, FWB: Functional well-being

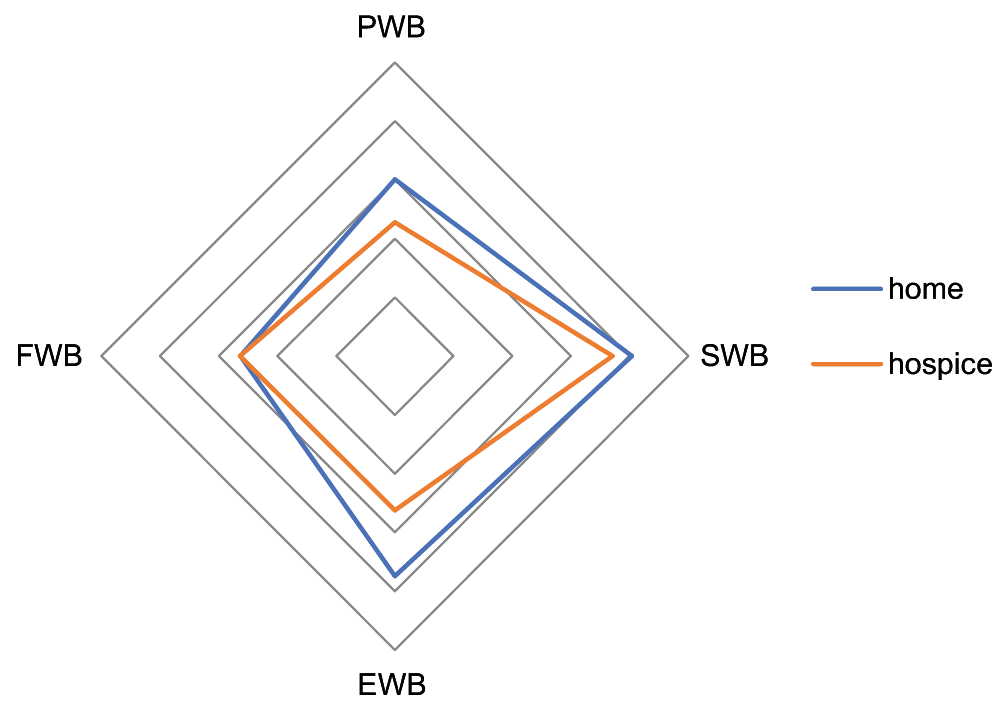

Among all the four subscale scores, PWB and EWB subscale scores were statistically significantly associated with the place of palliative care while the differences in the other two subscale scores were not associated [Figure 2].

- Illustrating subscale scores at both the settings.

FACT-G total score was high among patients receiving HO-based palliative care (mean = 67.64) compared to HS-based palliative care (mean = 56.56) and the difference between their total FACT-G scores was statistically significant (unpaired t-test = 2.20, P = 0.03) as represented in [Table 3].

| Subscale score | Place of palliative care | Unpaired t-test | Df | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home based (n=33) | Hospice based (n=35) | ||||

| PWB | 15.03 | 11.40 | 2.61 | 66 | 0.01 |

| SWB | 20.22 | 18.56 | 0.76 | 66 | 0.4 |

| EWB | 18.70 | 13.11 | 4.04 | 66 | 0.01 |

| FWB | 13.15 | 13.20 | 0.03 | 66 | 0.9 |

| FACT-G total score | 67.64 | 56.56 | 2.20 | 66 | 0.03 |

FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, PWB: Physical well-being, SWB: Social well-being, EWB: Emotional well-being, FWB: Functional well-being

Qualitative data findings

The study involved interviews of 68 patients, almost an equal number from the HS- and HO-based treatment. The themes that emerged from these interviews included the reasons why the patients preferred either HO or HS treatment/EOL care as mentioned in [Table 4]. The various reasons why they preferred either HO or HS care included staff behaviour – either good or bad, comfort and care, nutrition and moral support. The subthemes are highlighted in [Table 4]. Verbatims related to each are highlighted in [Table 5].

|

| Staff behaviour: Healthy doctor-patient relationship improved the spirit of patients especially when suffering from a terminal diagnosis. Findings illustrate that all staffs, whom patients and families came into contact with, had a critical influencing role in a patient’s end-of-life care. Many praised the high skill level of staff and their ability to meet care needs. a. Communication: Interview data highlighted good communication practices by staff members. They communicated in a timely, sensitive, supportive and compassionate manner both to patients and their family members, which were a great source of comfort to them. HS: ‘The doctors, nurses and the entire staff are very kind and respectful. The care and attention shown to my husband was excellent. They kept me informed, explained all stages of his illness and adequately addressed my concerns’. (Respondent 1) b. Professionalism: The attitude of staff, their professionalism, interpersonal communication and how they engaged with patients had a deep impact on them. HS: ‘The most impressive aspect was the degree to which the staff made me feel that my mother’s well-being was important, that our feelings were respected and there was a real sense of staff caring and not viewing the situation as ‘one of many cases’ – which of course it was’. (Respondent 2) c. Demeanour: The patients appreciated the courteous and sympathetic attention, they received and commented on their sensitivity and thoughtfulness. HS: ‘I experienced nothing but kindness and compassion. Their genuine concern and tenderness are above the call of duty. This means so much to me. I am forever in their debt’. (Respondent 3) ‘They care for me more than my family members. Because of their support I am still alive, because of them I can manage my condition’. (Respondent 4) HO: ‘I express my gratitude to this team. Even my relatives are not willing to take care of me in this condition’. (Respondent 1) d. Staff skills: Many commented specifically on the high skill level of staff members highlighting their compassion and dedication that left a significant impression on patients and their families. HS: ‘As I’ve said throughout this interview, the expertise, empathy and patience of this staff are impeccable. They also educate my family about wound dressing and symptom management. (Respondent 5) |

| Comfort and peace: The most commonly perceived role of palliative care was to provide symptom relief with an emphasis on keeping patients ‘as comfortable as possible. It conveyed a sense of peace in knowing that their family member was kept comfortable and entrusted to a competent palliative care team. a. Atmosphere: The general atmosphere in the campus or room was described as ideal or peaceful. HS: ‘I want to live here; this place is better than my home. If they discharge me, I want to request to stay here longer. At home, there is a lot of hustle but here I feel peaceful and relaxed. A garden, chirping birds, no hurries or running here and there for anything. Simply peace. I am healing now’. (Respondent 6) b. Pain and symptom management: The patient’s pain was effectively managed and the patient was well cared for. HS: ‘I can now sleep well without any pain or struggle which is having a positive impact on my health. They monitor me for any mild distress I experience’. (Respondent 7) HO: ‘I feel the palliative care team concentrates on patient-centred care. The doctors understand my pain and acknowledge my anxiety’. (Respondent 2) c. Provision of personal care: HS: I get to live in a separate personal room so I can peacefully recover. This is never possible at my home. (Respondent 8) HO: ‘Providing care right at the comfort of my home, who would have thought? Their regular visits give me assurance that I am on right track’. (Respondent 3) d. Access to palliative care outside normal working hours: They go the extra mile to treat terminally ill cancer patients at their homes despite their busy schedules, which was highly appraised among the patients. The frequencies of home visits by the team were based on the clinical severity and requirement of the patient. HO: ‘The team members never got angry or neglected me despite having the same complaints every visit. Nowadays, even my relatives have no time to visit me but these doctors are giving me their valuable time’. (Respondent 4) |

| Enough and consistent care: Terminally ill patients often need intensive care, sometimes even 24 h supervision. The availability of continual supervision gave them tranquillity. a. Staff availability: HS: ‘When I came here, I was so distressed. Despite my condition being so taxing the staff provided services day and night without any hesitation. Even in the middle of the night, they were there for me, never sighed on me and provided care calmly. I am more comfortable here than my’. (Respondent 9) b. Administration: HS: ‘Time management and administration are impeccable here. Each person in the team has a role from the wound dressing, monitoring my diet needs, and medications to monitoring my mental well-being. They come at their allotted times every day to make sure I am on track. It makes me feel secured about my health. I cannot ever get such meticulous and unconditional care at home’. (Respondent 10) |

| Nutrition: Timely well-balanced meals improved stamina and healing in patients. Practical aspects such as access to food and drink at low costs were thoughtfully taken care of. a. Facilities: HS: ‘The food services are punctual. It is more than sufficient, comes twice a day plus is well balanced and the quality also stays uniform every day. They even have options for oral cancer patients. At home, I can’t even afford to keep myself fed at all times. I feel much stronger and better healed’. (Respondent 11) ‘They provide a separate tiffin even for my wife who is staying here with me at low costs. For those like me who have oral cancer, they help me in the process of food intake. I am thankful to god to have shown me this place’. (Respondent 12) HO: ‘I look forward to these home visits. They assess me from my food habits, symptom and side effects monitoring to providing solutions to any discomfort I experience. I feel more secured this way’. (Respondent 5) |

| Moral support: Providing psychological support to the patient and their families increased their resilience and willpower to live their remaining days happily. a. Emotional and psychological support: The team’s caring and attentiveness signalled an emotional investment that was profoundly meaningful. Many appreciated the team’s attentiveness to the emotional needs of not just patients, but family members as well. HS: ‘My family was totally broken because of my condition. But here, we got positivity from the staff so that I can pass my remaining days with new boost. I got respect and empathy here’. (Respondent 13) ‘They changed my mindset. I wanted to give up, even thought of ending my life in this fight with my disease. Then, I was admitted here because I needed palliative care. Here, I got to know the staff who filled me with positivity and gave me a new purpose in life. Now, I want to live, I won’t die like this, I will live for my family and marry all of my kids and only when God calls me will I die’. (Respondent 14) b. Privacy: The importance of having access to home visits helped to facilitate difficult, sensitive conversations in private with the medical team was commented. HO: ‘I think that home is a congenial place to discuss with me and my family about advanced care planning regarding my condition. Their visits provide immense support and also facilitate my family’s acceptance of my death’. (Respondent 6) |

HS: Hospice, HO: Home

Thematic analysis of HS- and HO-based participants

HS

It was not merely the staff ’s clinical skills and expertise but their distinct sense of affection towards the beneficiaries of HS that was deeply appreciated by them.

HO

The HO-based palliative care team (from Community Oncology Centre) is established to meet the growing needs of palliative care in the community. After assessing patients’ symptoms and needs, they provide palliative care services such as pain and symptom management, medication, wound care, comfort care, psychological support and counselling and education of family caregivers on how to care for patients at HO.

The reasons for preferring HS care were not limited to staff behaviour, expert care and moral support provided by them but also the facilities and comfort that came with it while that for preferring HO care included the personalised skilled supervision available at their private HOs.

DISCUSSION

The present study has similar patient demographic profile as found in the study conducted by Singh[13] in Delhi, India. The qualitative data (primary component) in the present study strongly favours HS-based setting more than HO-based setting. The continuous presence of caregivers (professionals) is a cardinal benefit of facilities like HS, Casarett et al.[14] and a sense of safety is of utmost importance for terminally ill patients living at HO, Gott et al. and Goldschmidt et al.[15,16] The qualitative data of this study also show findings of similar perceptions of participants who make them prefer HS care over HO care.

The FACT-G total score is higher in patients receiving HO-based palliative care (67.64) than those receiving HS care (56.56) and the difference between the scores is significant. However, the patients undertaken in this study at both settings were given treatment by the same palliative team staff at some point, so further studies need to be conducted which take into account patients that are not at all in touch with the palliative team while receiving HO-based care to eliminate this confounding factor. Higher scores among HO-based patients may be a reflection of the fact that patients get admission to HS generally when they get worse and need advanced care. HO-based patients being closer to their families, HO environment and society as a whole were emotionally more secured contrary to HS centre that allowed only one family member to accompany the patient during their admission period, resulting in higher EWB scores in HO-based participants.

The actual choice of where to spend the last phase of life seems to be the result of negotiation between the patient and their families, in which the perspective of both is important, Gomes and Higginson.[17] Our study confirms this; because when the family members were not supportive, participants yearned to stay at the HS till their last breath. The moral support and consistent care provided by the HS staff had a significant impact in uplifting the lives of patients who were ready to give up due to their illness while the staff’s continual visits at patients’ HO s provided a sense of security to the patient’s family which helped them to better cope with distressing times.

CONCLUSION

Overall, with the primary component favouring HS care and higher scores obtained in HO-based patients, the present study advocates the necessity for the palliative services to expand their coverage regardless of whether they are provided at HS or HO; as it has improved the QOL of cancer patients significantly. Plus, when the HS patients were asked of choosing between staying at HO or in HS all of them had a definite answer of staying at HS. Not a single patient complained about the HS services, with many refusing to get discharged which are a huge success for palliative medicine in itself.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the study participants for their contribution to this research, as well as present and past investigators. The authors would specifically like to thank the HS staff at the Community Oncology Centre for their invaluable assistance and cooperation.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)-Short Term Studentship (STS): ref. no. 2019-07341.

References

- Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Problem. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer [Last assessed on 2019 Jun 30]

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Statistics. Available from: https://www.cancerindia.org.in/statistics/ [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 30]

- [Google Scholar]

- The growing burden of cancer in India: epidemiology and social context. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e205-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The global atlas of palliative care at the end of life: An advocacy tool. Eur J Palliat Care. 2014;21:180-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and World-Wide Palliative Care Alliance (WPCA); Global Atlas of Palliative Care at End of Life. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/global_atlas_of_palliative_care [Last accessed on 2019 Jul 30]

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3860-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- End of life decision-making for cancer patients. Prim Care. 2009;36:811-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organisation. Available from: https://www.nhpco.org/factsfigures/ [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 26]

- [Google Scholar]

- The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in cancer patients receiving palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:36-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How should clinicians describe hospice to patients and families? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1923-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Older people's views about home as a place of care at the end of life. Palliat Med. 2004;18:460-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expectations to and evaluation of a palliative home-care team as seen by patients and carers. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:1232-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: Systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332:515-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]