Translate this page into:

Compassionate Healthcare for Parents of Children with Life-limiting Illnesses: A Qualitative Study

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Chong L, Khalid F, Abdullah A. Compassionate healthcare for parents of children with life-limiting illnesses: A qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care 2022;28:266-71.

Abstract

Objectives:

Premature death of a child from a serious illness is probably one of the most painful experiences for a parent. This study examined the clinical experiences of bereaved parents of children with a life-limiting illness to provide recommendations for quality care.

Materials and Methods:

Data were collected using semi-structured in-depth interviews with bereaved parents whose children had died at least 3 months before the interview. Parents were purposively sampled from two institutions offering end-of-life care to children with life-limiting illnesses. Data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results:

Data analysis revealed three main themes: (1) Clinical communication, (2) Healthcare infrastructure and (3) Non-physical aspects of healthcare. The seven subthemes uncovered were as follows: (1) Honesty and clarity, (2) empathy, (3) interdisciplinary communication, (4) inconveniences in hospital, (5) home palliative care, (6) financial burden of illness and (7) psychosocial and spiritual support.

Conclusion:

Strategies to improve healthcare for children and their families are multifold. Underlying the provision of quality care is compassion; a child and family-friendly healthcare system with compassionate providers and compassionate institutional policies are vital components to achieving quality healthcare. Culturally sensitive psychosocial, emotional and spiritual support will need to be integrated as standard care.

Keywords

Paediatric

Palliative care

Bereaved parents

Patient-centred care

Family-centred care

INTRODUCTION

Premature death of a child from an incurable illness is probably one of the most painful experiences for a parent. These parents constantly face challenges when making healthcare decisions. Current medical science and technological advancements may help delay death for some neonates and children.[1,2] However, most interventions focus on quantity over quality of life.

Parents may experience distress in many domains during their child’s illness trajectory. Some bereaved parents report a tumultuous journey, from exasperations with the curative culture of providers, inadequate psychosocial and spiritual care, to experiences of emotional upheaval.[3] Moderate-to-severe levels of depression and anxiety during their child illness have also been reported.[4] Religious practices and spiritual support help maintain a sense of peace and calm for some parents.[5] External factors such as healthcare systems and processes can affect the quality of lived and dying experiences by patients and families.[6]

Palliative care for these families helps in reducing symptoms, improving quality of life and mitigating distress.[7] Families need guidance to navigate the often complicated illness journeys to align with their beliefs and values. In 2014, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution for palliative care to be implemented as part of universal health coverage around the world.[8] Until there are equitable specialist palliative care services, all healthcare providers will need to embrace and provide general palliative care to ensure quality healthcare is delivered to children and their families.

We proposed to examine the healthcare experiences of bereaved parents and hope that their personal experiences will provide insights into add, inform, strengthen and subsequently guide both the education of providers and the provision of quality care to children with life-limiting illnesses and their families.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We conducted a qualitative semi-structured in-depth interview with purposively sampled bereaved parents of children with a life-limiting illness. This study adopted the constructivist paradigm to explore their experiences, challenges and care needs.

Parent selection

We recruited bereaved parents from two centres caring for children with life-limiting illnesses in Kuala Lumpur. Hospis Malaysia (HM) is the largest home palliative care service and University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC) a tertiary university hospital without a specialist palliative care service in the period studied. Recruitment of parents was in 2 time periods due to unforeseen circumstances. English or Malay speaking parents were eligible for the study if their child had a life-limiting illness and had died more than 3 months before our contact. Separate institutional ethics approvals were obtained.

Information about the study was mailed to parents. After a week, a trained research assistant, uninvolved with patient care, contacted parents by telephone. If parents consented to participate, a convenient date, time and location were arranged. Parents could choose to be interviewed together or separately and given a choice for interview location (e.g., HM, UMMC, home or work place). If they had not received the Study Information Sheet by mail, they were given the option to receive it by e-mail or be given it on the day of the interview. They were given a contact number to call if they changed their minds about participating. For parents who were not interested to participate, reasons were noted if revealed.

Data collection

Interviews were carried about from July 2017 to January 2019 for patients who died between 1 April 2016 and 31 March 2017 at HM and between 1 August 2017 and 30 April 2018 at UMMC. Signed written consent was collected at the interview. Parents were allowed to withdrawal from the study before, during or after the interview was conducted.

An interview guide developed from literature review and local expert opinions were used [Table 1]. All three authors conducted the interviews in English or Malay according to parent’s preference. Authors had no prior relationships with the parents they interviewed. The interviews were all audio-recorded and field notes taken to guide analysis.

| Introduction |

| Please tell me what condition did your child have? |

| Please tell me who first told you about it? |

| How was your experience in hospital? |

| Experience of care, staff interactions |

| How was the hospital staff’s interaction with you? |

| How was the hospital staff’s interaction with your child? |

| What do you think was your child’s experience in hospital? |

| Please tell me of any helpful/positive experience with the hospital? |

| Can you tell me more about your relationship with your child’s medical team in the hospital? |

| What was good about the care your child received? |

| Was there anything that was negative in your experience? |

| How do you think it could be improved? |

| Knowledge processes |

| Please tell me how you received information? |

| (diagnosis, during illness, prognosis, procedures, investigations and EOL) |

| Communication |

| Please tell me how the medical team usually communicated with you |

| Please tell me what kinds of things said or done when the medical team communicated well. |

| Parental role, care for siblings |

| Did you feel that all your needs were met? If not, what wasn’t? |

| Were you adequately supported during your child’s illness by the hospital? |

| If so, in which areas? …….If not, which areas could be improved? |

| How did you find your role as a parent change when in hospital? |

| Do you have other children? Was there any concern extended to your other children when your child was cared for? |

| Were your child’s needs met when at hospital? |

Data analysis

The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim without identifying information. The transcripts were checked by authors (LAC and FK) for accuracy. Transcripts were coded with NVivo Version 10.2.2. Coding involved the examination of each line of the transcript to establish the meaning. All three authors coded two transcripts independently and compared codes that resulted. A coding framework was created and refined together; and used to then code the other subsequent transcripts. Categories and themes were generated following discussion and agreed by consensus. Original quotes were extracted to illustrate the themes. Extracted quotes in Malay were translated and modified to improve readability.

RESULTS

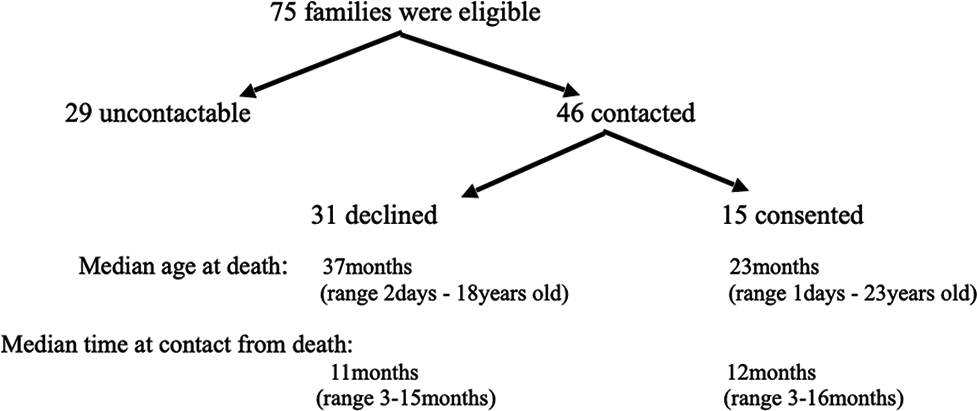

There were 75 eligible families identified. Of that, 29 (38.7%) families were uncontactable by telephone. From those contacted, 15 (32.6%) families consented to participate [Figure 1]. A total of 22 parents from these 15 families were interviewed [Table 2]. All consenting parents of the same child chose to interview together. The interviews lasted between 26 min and 120 min.

| Patient (n=15) | Recruiting centre | Parent | Ethnicity | Child’s diagnosis; | Child’s age at death | Location of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HM | Mom | Malay | Quadriplegic cerebral palsy | 19 years 11 months | Hospital |

| 2 | HM | Dad | Malay | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | 15 years 7 months | Hospital |

| 3 | HM | Mom and dad | Chinese | Berdon syndrome. (megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome |

20 days | Home |

| 4 | HM | Mom and dad | Malay | Metastatic osteosarcoma | 10 years 4 months | Hospital |

| 5 | HM | Mom | Malay | Metastatic Ewing sarcoma | 14 years 6 months | Home |

| 6 | HM | Mom | Chinese | Metastatic angiosarcoma | 17 years | Home |

| 7 | UMMC | Mom | Malay | Relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia | 9 years | Hospital |

| 8 | UMMC | Mom | Malay | Trisomy 21, acute myeloid leukaemia | 1 year 11 months | Hospital |

| 9 | UMMC | Mom and dad | Malay | Liver failure, giant cell hepatitis | 7 months | Hospital |

| 10 | UMMC | Mom and dad | Indian | Coarctation of aorta, ductal dependent, necrotising enterocolitis | 17 days | Hospital |

| 11 | UMMC | Mom | Malay | Hydrops foetalis | 1 day | Hospital |

| 12 | UMMC | Mom | Malay | Complex cyanotic heart disease | 8 days | Hospital |

| 13 | UMMC | Mom and dad | Malay | Lung hypoplasia, severe pulmonary hypertension | 7 months | Hospital |

| 14 | UMMC | Mom and dad | Chinese | Biliary atresia, post-Kasai, liver failure | 23 years 2 months | Hospital |

| 15 | UMMC | Mom | Malay | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 6 months | Hospital |

HM: Hospis Malaysia, UMMC: University Malaya Medical Centre

- Flowchart of interviewed parents.

Three of the children from HM did not die at home; one died in hospital following referral at end of life, another died in hospital following an acute illness unrelated to primary diagnosis and the third died when visiting his grandparents in another state. All nine patients from UMMC were either not referred or had no home palliative care services where they lived. They all died in hospital.

The three main themes and seven subthemes that emerged from the data will be discussed [Table 3]. This study suggests that improved communication skills and compassion from providers and the healthcare system is required to improve parent’s clinical experience.

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Clinical communication | Honesty and clarity Empathy Interdisciplinary communication |

| Healthcare infrastructure | Inconveniences in hospital Home palliative care |

| Non-physical aspects of care | Financial burden Psychosocial and spiritual support |

Healthcare communication

Honesty and clarity

Most parents were satisfied with the medical information received. Dissatisfied parents sought information on their own from Google, YouTube or their personal social network. Some parents felt that they had to be prepared with some information to be able to ask the right questions and obtain more clarity from providers. Others felt that providers consciously did not reveal much so as to not overwhelm them and they may not have understood anyway.

Some parents were anxious and frustrated at the delay in diagnosis and the multiple, often expensive and perceived futile investigations. This led to disappointment and distrust with the healthcare system. Similarly, at the end of life, some parents perceive that healthcare providers continued to be unrealistically hopeful despite their child’s deterioration in intensive care. Unclear communication continued to cause persistent distress in bereavement.

Some parents noticed healthcare providers avoid medical discussions with their child and it was challenging for parents to be truthful to their child themselves.

‘…they didn’t explain to us parents…my heart aches…If they honestly told us, it would be easier for us.’ ‘I’m disappointed…the doctors… give us hope with options, Option 1…Option 2…Option 3….but till her death, I didn’t see her awake…’.

‘The doctor would not explain to him directly… I had to be clever to avoid telling him…but sometimes he knew and would say mom, you are lying.’

Empathy

Parent’s experience revealed perceived insensitivity and lack of compassion from some healthcare providers. Parents describe being unprepared and shocked when told that their child had a diagnosis of a serious condition. Lack of empathy resulted in anger and frustration. A working single parent who was not always able to be at her adolescent child’s bedside during chemotherapy felt judged.

‘…the doctor was like…very straightforward…okay, there’s no hope… just give up!…I was not happy with him saying all that…’

‘Initially I was angry…we are very disappointed. I never want to go there again!’

‘I want to work, I want to be with my child…there are understanding doctors…some don’t understand and don’t care to understand, they don’t want to know.’

Interdisciplinary communication

One parent shared that their child with a complex illness was cared for by multidisciplinary teams and the medical care was fragmented and organ systems based. Information was presented to them in silos.

‘Professor Y was good, he explained…But because Professor Y didn’t take care of the heart…or the other parts…so he didn’t explain…he only explained his part, that’s it.’

Healthcare infrastructure

Inconveniences in hospitals

Parents highlighted many inconveniences and hospital policies that could have been more compassionate toward families. Pharmacy services, uncomfortable waiting areas at intensive care, restrictive visiting hours, intrusions by staff and medical students were some of the grievances parents had. Other inconveniences parents experienced were challenges in finding their way to the various appointments in different departments, prolonged waiting times, finding parking with their child who is wheelchair bound, mobile phone charging facilities on the ward and confusing post death procedures.

‘…it’s fine that we need to pay…but why do we need to go…leave my baby…go pay and pick it (medication) up ourselves…such inconvenience when it can be charged to the bill…’

‘It’s quite tiring…and have no where else to go…I sit close outside….but I really want to spend time in there with my boy’

Home palliative care

All parents who received home palliative care shared that they had not heard of it before referral. They all had perceived that palliative care was for the terminally ill. All who received home care were appreciative of the service and felt that it was responsive to their individual needs. The choice of being able to be cared at home was appreciated. One parent who moved interstate and received home care from a maternal and child health service noticed the difference from a specialised palliative care service.

‘The community nurses have no experience, they see pregnant women and newborns and have no experience with palliative care…I think palliative care is needed… needed everywhere…’

‘I was surprised…at least there is something to back me up…I’m not alone…they really helped me a lot at the time when she was seriously ill.’

Psychosocial and spiritual care

Financial burden of treatment

Parents in this study shared the distress and impact from the financial burden during care for a child with a life-limiting illness. The hospital fees were not their only financial burden, they had additional food expenses for their child and parking fees, especially for those out of town. Foreigners or immigrant parents were burdened when charged more and had no access to the government assistance which were for citizens only.

‘We did asked for help…it was like begging…we are now still in debt, my husband had borrowed from ‘Ah Long’ (moneylenders).’

Psychosocial and spiritual support

Parents acknowledged and appreciated the medical and nursing care received and parents of children with cancer felt ward staff were like family. However, emotional, psychological and spiritual support for the adolescent patients, their siblings and parents were perceived to be lacking. The importance of maintaining spiritual strength during the illness journey was highlighted by one parent. Parents found other parents who had previously gone through similar experiences helpful in supporting them. For patients with cancer, often peer relationships formed in hospital resulted in strong bonds which continued out of hospital and during readmissions. Some parents also valued opinion from their extended family in decision-making. Two parents admit to knowingly prioritising the needs of their ill child over the siblings.

‘…they are focused more on…the sickness…there is no counselling for the family…’

‘…to provide emotional support…first, primarily for the patient. Second, for the parents. and third, for the siblings…it is a challenge for the medical team.’

‘At one stage, my daughter was very…emotional…she was very bitter…she went through a very tough time. For parents…for me…it is a very lonely journey.’

‘There needs to be a proactive effort…Perhaps once a week to read ‘yasin’ (prayer)…there may be a time they feel ‘lost’. As a Muslim, I feel that there is ‘space’ where parents can be ‘lost’, their spirit may be challenged, there may be whisperings to weaken their spirit.’

‘…my husband tended to be over-protective…sometimes the siblings, they quarrel…he will get mad and always scold them…they always feel, they are not being loved…all of them were very jealous of her…’

DISCUSSION

There are several important findings in this study that offers opportunities to improve care for families of children with a life-limiting illness. The personalised views of parents are undoubtedly unique to each family. However, taken together, they can guide healthcare services to meet the needs of these families.

The overarching healthcare core value emerged from this study is one of compassion. The lived experience of parents in this study suggests distress from multiple aspects; poor communication from providers, especially at diagnosis and end of life, facilities that are not child and family friendly and the need for better psychological, emotional and spiritual support for families throughout their disease trajectory.

Provider’s conversations with families need to address each family member’s individual understanding and needs, when done poorly, can have a deep and prolonged impact. Trusting and honest relationships are vital for quality care. Honest information shared throughout the illness helps maintain a trusting doctor-parent and doctor-patient relationship.[9,10] It has been reported that most healthcare providers do not have sufficient empathetic communication training to approach patients with serious illnesses.[11,12] The various functions of hope to each patient and family may help healthcare professionals tailor their communication.[13] Discordance in recognising the importance of hope among parents and healthcare providers in this study has been reported.[9] From this study, it is clear that individualised and family-centred care is urgently needed to help direct conversations to benefit families. Healthcare providers also need to be mindful of young patients who want information about their illness and to guide parents who may not know how to share distressing news with their children.

Patient and parental need for psychosocial and spiritual support fluctuates during the illness and was sought for by families in this study. Integrating non-physical domains to clinical care to maintain and facilitate resilience during the illness journey will be appreciated by parents.[14] It has been shown that perceived social support correlates with parental anxiety.[15] The valued culturally appropriate social support also reflects the inherent social-centric cultural norms of some of our study population.

Another area of attention was the inconveniences of the hospital infrastructure. A mindset change of administrators and healthcare staff will be required. Billing procedures will need to be more considerate and compassionate toward families. There is evidence that availability of specific patient and family-centred healthcare strategies will improve patient and family’s experience and quality of life.[16] Caring for and getting treatment for a child with a serious illness results in a life changing experience for parents.

An interdisciplinary framework would also help improve the integrity of information and support provided to families. The presence of a healthcare coordinator for the child and family will help families navigate through a complex healthcare system. Compassionate institutional policies are required to achieve quality care.

This study demonstrated that the pursuit for an accurate diagnosis can result in physical, emotional and financial burden. Reasons for delay can be postulated to be due to failure of the individual’s healthcare provider, the hospital’s health delivery system or management of national healthcare information. Highly subspecialised paediatricians may be unaware of the expanding breath of medical diagnoses and do not refer patients expediently. Impact of the financial cost incurred during diagnosis and treatment can persist after death and continue to impact the rest of the family.

At the end of life, ensuring non-abandonment by primary teams and being told that dying is imminent was important to parents. One father talked about not knowing death was imminent; ‘I would have hugged her…do more.’ It has been reported that fathers who were not been able to say farewell to their child in the way they wanted have an increased risk of complicated grief.[17] Healthcare providers have to be reminded that compassionate end-of-life care improves quality of parental bereavement.

Parents and healthcare providers are still relatively unfamiliar about palliative care in Malaysia. All parents in this study who received home palliative care found it met their needs and were an appreciated source of support. Developing palliative care services in the community will enable quality care and continuity of care for families.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The appropriate time to contact bereaved parents to participate in research is unclear as grieving process of each parent varies. Siassakos et al.[18] contacted bereaved parents 6 weeks post-discharge to avoid recall bias. Butler et al.[19] recommends 6 months–2 years after a child’s death. They concluded that respecting each parents’ autonomy to participate or refuse is more important than finding a time frame that is least distressing for each parent. In this study, we ensured parents participated without coercion or obligation and had opportunities to withdraw participation.

A third of parents who were contactable consented to participate in this study. The median age at death and time from death to contact of both groups of parents who declined and who participated were not clinically different. Findings from this study do not represent other hospitals and home palliative care services. Most parents did not reveal the reason for not participating. For two parents, the potential emotional burden was the reason for declining. We acknowledge that we may have missed other insights from the narratives of parents who declined and those uncontactable. However, we hope findings here contribute to the pool of qualitative studies on palliative care for children.

CONCLUSION

Strategies to improve services for children with life-limiting illnesses are multifold. Healthcare providers will benefit from specific training on compassionate communication skills. Psychosocial, emotional and culture-sensitive spiritual support needs to be integrated as standard care from diagnosis to mitigate suffering and distress. Compassionate institutional policies and a child and family-friendly healthcare system will complement palliative care when provided. While the illness journey from diagnoses to death and into bereavement may vary in different families, compassion, respect and skilful communication will help ensure quality care and mitigate suffering experienced by families.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Yong Yi Leng and Dr. Narmatha Darshini Nanthini A/P Subramaniam who helped as research assistants on this project and the doctors at HM for their support.

Declaration of patient consent

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moral distress in the neonatal intensive care unit: What is it, why it happens, and how we can address it. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:581.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lived experience of a child's chronic illness and death: A qualitative systematic review of the parental bereavement trajectory. Death Stud. 2019;43:547-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety and depression in bereaved parents after losing a child due to life-limiting diagnoses: A Danish nationwide questionnaire survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58:596-604.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality or life philosophy in tough times. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:39-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions of a good death in children with life-shortening conditions: An integrative review. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:714-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improved quality of life at end of life related to home-based palliative care in children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:143-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resolution WHA67.19: Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Comprehensive Care Throughout the Life Course In: World Health Assembly. 2014. p. :37-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Problems and hopes perceived by mothers, fathers and physicians of children receiving palliative care. Health Expect. 2015;18:1052-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial profiles of parents of children with undiagnosed diseases: Managing well or just managing? J Genet Couns. 2018;27:935-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers in care for children with life-threatening conditions: A qualitative interview study in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035863.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development of a stakeholder driven serious illness communication program for advance care planning in children, adolescents, and young adults with serious illness. J Pediatr. 2021;229:247-58.e8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Should palliative care patients' hope be truthful, helpful or valuable? An interpretative synthesis of literature describing healthcare professionals' perspectives on hope of palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 2014;28:59-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supporting parental caregivers of children living with life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses: A Delphi study. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2018;23:e12226.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The association of perceived social support with anxiety over time in parents of children with serious illnesses. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:527-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:844-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors during a child's illness are associated with levels of prolonged grief symptoms in bereaved mothers and fathers. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:137-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- All bereaved parents are entitled to good care after stillbirth: A mixed-methods multi-Centre study (INSIGHT) BJOG. 2018;125:160-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereaved parents' experiences of research participation. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:122.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]