Translate this page into:

Concerns of Health-care Professionals Managing COVID Patients under Institutional Isolation during COVID-19 Pandemic in India: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sushma Bhatnagar, Department of Onco-Anaesthesia and Palliative Medicine, Dr. BRAIRCH, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi - 110 029, India. E-mail: sushmabhatnagar1@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

Health-care professionals (HCPs) are the frontline warriors in the time of this uncertain and unpredictable crisis of COVID. They face many challenges while caring for these patients, yet they are expected to cope with it and deliver their duties for the betterment of humankind. Our primary aim was to identify and assess the concerns of HCPs working in COVID area in a tertiary institutional isolation center.

Methodology:

An online Google-based questionnaire survey was distributed through various social media platforms after approval of the institutional review board to a total of 100 HCPs who were treating and managing COVID-positive patients.

Results:

Of 100 responses, 72% were concerned about the risk of infection to self and family, while 46% reported disruption of their daily activities at a personal level. At the institutional level, 17% were concerned about inadequate personal protective equipment-related challenges. 20% had inadequate knowledge and training about COVID. 16% of participants were anxious all the time, 11% feared all the time, and 12% had stress all the time while treating COVID patients. Connectedness and communication with family and friends, word of appreciation, music, and TV were few strategies to cope up with these challenges.

Conclusion:

There is a need to identify and address the concerns and challenges faced by HCPs and to develop a comprehensive strategy and guideline to provide a holistic care and to ensure their security in the workplace.

Keywords

Concern

coping

health-care professionals

online survey

INTRODUCTION

The viral pandemic COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 isolated from Wuhan, China, and spread to almost all the countries.[1] The high rate of morbidity and mortality poses as a big setback. There are 4,993,470 confirmed cases with 327,738 deaths reports as of May 22, 2020 with a global mortality rate of 3.4%, according to the WHO.[23]

Health-care professionals (HCPs) are the vital resources and frontline responders in every country. The pride of being in a noble profession and the moral obligation to take care of COVID patients cannot be burdened by unacceptable risks.4 It carries a high risk for HCPs because it can be transmitted even when the disease progresses asymptomatically in some patients.[5]

The uncertainty in clinical presentation, symptoms, nature of transmission along with increased morbidity and mortality are potential triggers creating concerns in the health-care workers (HCWs) dealing at frontline in the current pandemic. The concerns range from fear of acquiring infection, inadequate personal protective equipments (PPEs), feeling of inadequately supported at work, and worrying about the transmission of infection to peers and family members. Moreover, at the personal level, the HCP may have concerns related to stigma and discrimination by peers, neighbors, and society. Due to lockdown, food and transportation have also become a big challenge. This indirectly will lead to stress, anxiety, fear in work, frustration, adjustment issues, and psychological fears.[6]

This stress can be decreased when they are guaranteed a safe atmosphere with well-equipped safety gears such as PPEs. Balancing activities of life, remaining connected with peers and family, and appreciation by society are few strategies to overcome stress. Thus, our study attempts to find the concerns and challenges of HCPs treating COVID patients and the coping strategies they are adopting to overcome these challenges.

METHODOLOGY

Primary objective

The primary objective of the study was to assess the concerns and challenges faced by HCPs who are posted in managing the COVID patients in institutional care in a tertiary care center.

Secondary objective

The secondary objective of the study was to find the coping strategies adopted by HCPs in their personal and workplace areas

Study design and participants

We did a descriptive cross-sectional study using an online survey developed by Google form. Participants were recruited through snowball sampling. Doctors, nurses, and administrators who were recruited from their original department and posted for the care of COVID-19-positive patients in a tertiary care center for isolation were enrolled in our study.

Data collection

Ethical clearance for this study was received from the members of the institutional review board. The sampling technique used was a snowball. An online Google-based survey was distributed through various social media platforms, including WhatsApp and e-mail to a total of 100 HCPs. A consent form explaining the study and participation was appended to it just before the starting of the survey sections. On receiving and clicking on the link, participants were auto-directed to the information and consent section. On accepting and agreeing to participate, they were directed to different sections of the questionnaire which included the basic demographic details, challenges faced by HCP, and coping strategies adopted for the same. A convenient sampling was done, and the responses of 100 surveys were assessed.

Data analysis

The data were recorded in a Microsoft Excel chart and descriptive analysis was done.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristic

An online survey related to concerns and challenges of HCPs and their coping strategies for the same was conducted in a tertiary care center. A total of 100 responses were recorded. The study included only those who had access to the Internet and who understood English. Doctors comprised majority of participants with 62% response which included senior residents, junior residents, faculties, and one administrator. There were 38% of nurses in our study. Fifty percent of the participants were each in the age group of <30 years and 30–45 years. Sixty-nine percent were male and 31% were female. Fifty-nine percent of participants were married [Table 1]. All of the HCPs were directly involved in treating and caring of COVID19 positive patients.

| Sociodemographic details | n=100 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 69 |

| Female | 31 |

| Age (years) | |

| <30 | 50 |

| 30-45 | 50 |

| >45 | 0 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 59 |

| Unmarried | 41 |

| Designation | |

| Faculty | 9 |

| Senior resident | 32 |

| Junior resident | 20 |

| Nurse | 38 |

| Administrator | 1 |

Concerns and challenges

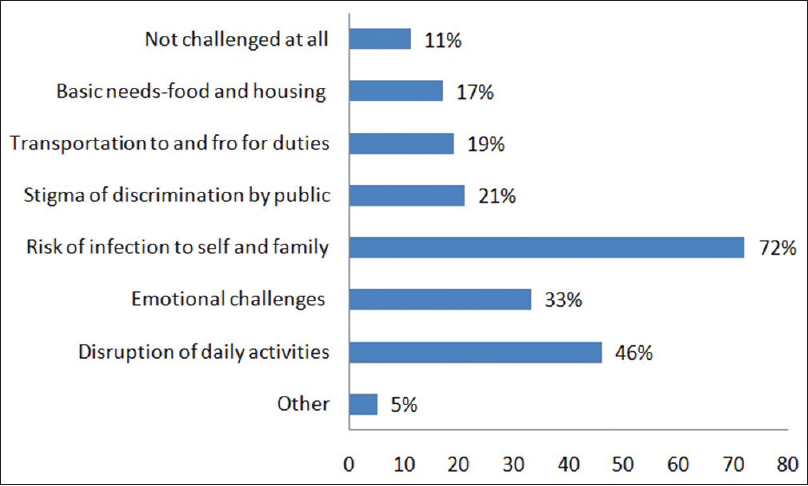

On responding to the challenges faced by HCPs at a personal level, 72% feared of risk of infection to self and transmitting to family. Forty-six percent reported disruption in their daily activities. Concerns of basic food and housing during lockdown were reported in 17% while transportation to and fro from the workplace among lockdown was a big problem for HCWs, as few stayed with their families far away from the tertiary care isolation center [Figure 1].

- Challenges faced by health-care professionals at personal level

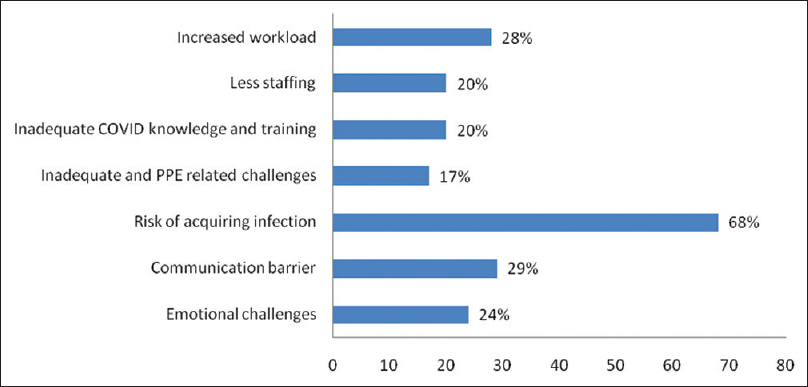

The challenges observed by HCPs in the institution were again the risk of acquiring infection from the patients. Twenty-eight percent complained of increased workload. Seventeen percent of participants were concerned about inadequate PPE, while 20% had inadequate knowledge and training of COVID. This increased their level of concerns [Figure 2].

- Challenges faced by health-care professionals in the institution

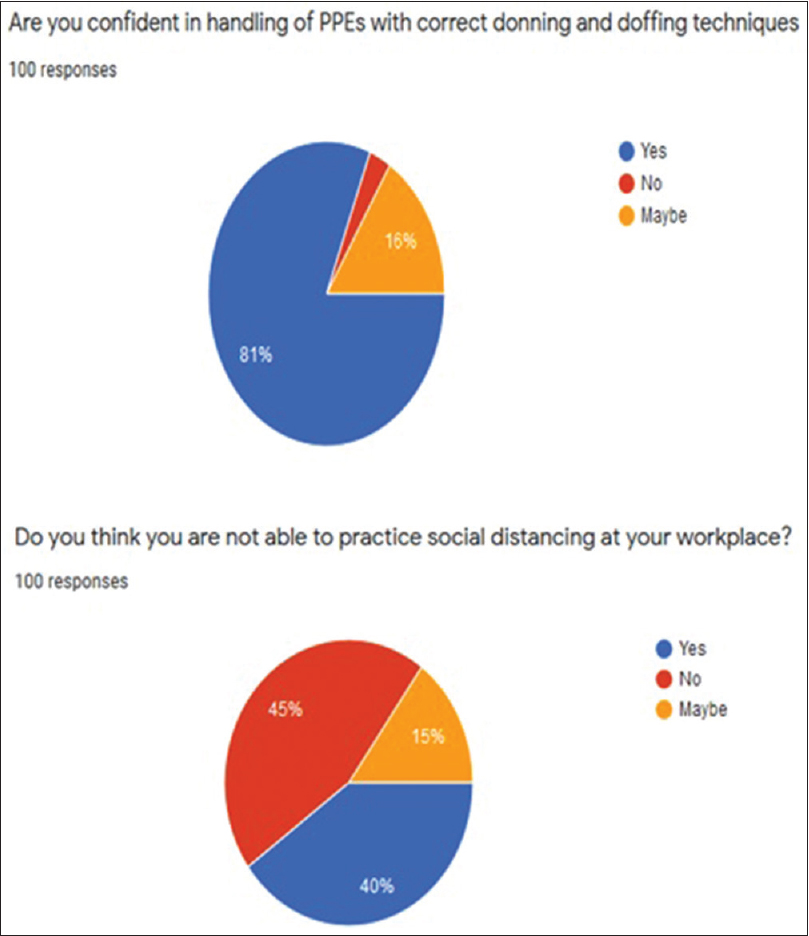

On assessing the level of stress, anxiety, and fear using the Likert scale, 26% had no stress and 30% had stress half of the time while managing COVID patients. Twenty-four percent of the participants had no anxiety at all, while 16% were very anxious all the time while managing the COVID patients. One percent of the participants feared even while away from work, while 29% were confident and had no fear while managing COVID patients [Table 2]. Eighty-one percent of the participants were confident in handling PPEs, while 3% were not at all confident in handling. Forty percent of the participants think that they are not able to maintain social distancing in their workarea [Figure 3].

| Level of stress while managing COVID patients | |

|---|---|

| Level | Number of participants |

| No stress at all | 26 |

| Stress sometimes | 29 |

| Stressed half of the time | 30 |

| Stressed all the time | 12 |

| Stressed when away from work | 3 |

| Level of anxiety while managing COVID patients | |

| No anxiety at all | 24 |

| Anxiety sometimes | 35 |

| Anxiety half of the time | 23 |

| Anxiety all the time | 16 |

| Anxiety when away from work | 2 |

| Level of fear while managing COVID patients | |

| No fear at all | 29 |

| Fear sometimes | 33 |

| Fear half of the time | 26 |

| Fear all the time | 11 |

| Fear when away from work | 1 |

- Handling of personal protective equipment and practicing social technique at work place

Coping strategies

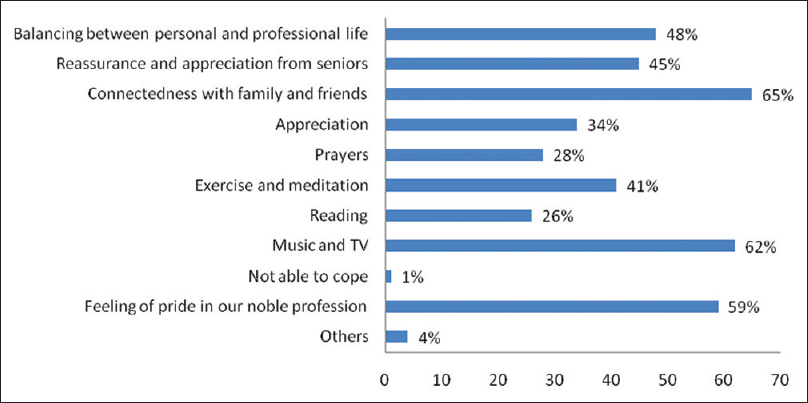

Coping strategies really help the HCPs in increasing their morale and taking care of patients more efficiently. Sixty-five percent of the participants reported communication and connectedness with family and friends as the driving force for motivation. Forty-eight percent kept a good balance between their personal and professional lives. Sixty-two percent enjoyed music and TV, 41% did exercise and meditation, while 26% preferred reading as a coping mechanism. Thirty-four percent liked when appreciated for their work. The feeling of pride that this is a noble profession was responded by 59% [Figure 4].

- Strategies taken for mental wellbeing at personal level

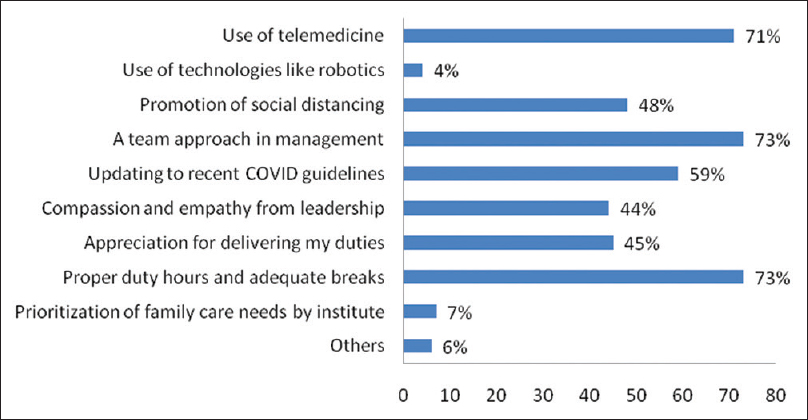

Strategies taken by the institution to help the HCPs overcome their concerns and challenge is by providing a safe environment and minimizing any risk which can cause confusion and stress in their minds. A good team approach in management was responded by 73% of participants. Similarly, proper duty hours and adequate breaks between duties to decrease burnout were responded by 73 % of participants. Compassion and empathy from a good leadership to increase the morale and confidence of HCPs is very important and was appreciated by 44% of our participants [Figure 5].

- Strategies taken at institution which helped healthcare professionals to cope better

Seven percent of the participants wanted to seek a professional help from a counselor, psychiatrist, or senior to help cope with concerns, whereas other participants were coping the situation well. Though psychosocial concerns are less, but still intervention should be taken for the health care professionals facing trouble coping with the COVID-19 pandemic.

DISCUSSION

HCPs are the leaders when it comes to managing the COVID infection worldwide. They can be considered as soldiers, and the only weapon they carry is the amount of knowledge, awareness, and attitude during this pandemic. In addition to physical health, they need to maintain their mental and personal well-being as well. Due to uncertainty in its presentation and outcome, HCPs are prone to have psychological distress and mental illness.[7] Anxiety, fear, and depression are very common post COVID.[8] Our study has also shown the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and fear among the HCPs while dealing with COVID patients.

For smooth and optimum working of HCPs, it is necessary to provide them a safe environment with adequate PPEs so that they do not fear about the risk of infection transmitting to them.[4] Adequate knowledge and training about PPE and its proper disposal are very essential. In our study, 17% faced challenges due to PPE, while 20% had inadequate knowledge and training regarding PPE and the disease. Lockdown poses a great amount of difficulty in providing the basic needs such as food and shelter.[4] HCPs have to manage for transportation to and fro from the institution with great difficulty, and the basic concerns should be addressed so that the quality of work is not compromised.

Social distancing among COVID must be followed at all costs. It can be transmitted by the patient or asymptomatic contact.[9] In our study, 40% of the HCPs are not able to maintain social distancing and can be a cause of transmission. A qualitative study of medical residents during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Toronto showed that anxieties around personal safety and risk of contagion to loved ones conflicted with their professional duty to care.[10] Furthermore, our study reports the risk of infection to self and family (72%) as one of the main challenges faced.

At health institutions, there are always many hotspots of acquiring infection either from the patient or other staff or common places such as canteens and washrooms. The basic challenge faced by HCP at the health institute is the high chance of risk of acquiring infection in our study (68%). In one of the studies reported, the possibility of being sources of infection, being isolated/quarantined, putting family members and other staff at risk, fear of improper use of PPE, fear of household problems due to lockdown, and medical insurance constitute the main burdens. The possible solutions proposed are an increase in workforce and better community awareness to reduce stigma.[11]

There is a growing disparity between the demand and supply of resources, with the number of cases rising exponentially. Our study reports that 17% of the HCWs had concerns related to the lack of PPE, which is true for most of the developing countries, showing a lack of preparedness.

There are various steps taken by the institution which include the use of telemedicine as reported by 71% of the participants to decrease the contact time between patient and staff and adequate duty hours and breaks. Collaboration and coordination between multiple groups in the task force is a prerequisite for optimal service delivery. A good team leader will always lead by example and boost the morale of juniors and colleagues. A healthy balance between professional and personal life is necessary. Connectedness with friends and family helps alleviate anxiety during pandemics.[12] Meditation, exercise, music, and TV prayer and reading are other coping mechanisms by which one keeps himself/herself calm and stress-free.

In a cross-sectional study, Liu et al. pointed out that mental health professionals may need to work closely, especially with those working in critical care units, to minimize stress levels and reduce the risk of depression, while Kang et al. noted the positive impact of telephone helplines for HCWs to specifically address mental health problems.[1314]

In a qualitative study done by Sun et al., on study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients, they investigated the psychological experience of nurses and found negative emotions dominant in the early stages of COVID-19 outbreak and reported that coping methods and psychological growth are important for maintaining mental health.[15]

Our suggestions: To increase the motivation of HCPs working in COVID designated areas, the institute should ensure:

-

Basic needs such as food, housing, and proper transport for the duty

-

A team approach should be made where the leader shows compassion, guides, and appreciates the HCPs

-

Ensuring adequate availability of good-quality PPEs

-

An area for recreation and relaxation for HCPs

-

Timely financial aid

-

To have a dedicated psychological intervention team for those who have a tough time with poor coping skills

-

Thermal screening and testing for HCPs during the end of the posting.

Limitation

This particular study is a survey, so only participants knowing English and having smartphone and e-mail IDs were eligible. Our sample size is very small; therefore, a bigger multicentric study needs to be conducted to accurately assess the psychological impact of those directly dealing with COVID-19.

CONCLUSION

The COVID pandemic has caused great distress in the lives of HCWs because of the uncertain nature of its course, infectivity, morbidity, and mortality. Hence, there are many concerns and challenges of a HCP at the personal as well as institutional level. A comprehensive strategy and guideline framework under a good leadership is the need of the hour to overcome these hardships and provide HCPs a healthy and safe environment where they can work without any compromise.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Clinical presentation and virological assessment of hospitalized cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in a travel-associated transmission cluster 2020. MedRxiv 2020030520030502; doi: https://doiorg/101101/2020030520030502

- [Google Scholar]

- Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1439.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attending to the Emotional Well-Being of the Health Care Workforce in a New York City Health System During the COVID-19 Pandemic Academic Medicine 2020. Publish Ahead of Print doi: 101097/ACM0000000000003414

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: Increased Transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – Sixth update. Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2020.

- Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102080.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2019-nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. 2020;395:e37-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;52:102066.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: https://wwwcdcgov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcphtml cited 2020 Jun 18

- Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med (Lond). 2004;54:190-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Issues relevant to mental health promotion in frontline health care providers managing quarantined/isolated COVID19 patients. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102084.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: Peer Support and Crisis Communication Strategies to Promote Institutional Resilience. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:822-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Critical care response to a hospital outbreak of the 2019-nCoV infection in Shenzhen, China. Crit Care. 2020;24:56.

- [Google Scholar]

- The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e14.

- [Google Scholar]

- A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:592-8.

- [Google Scholar]