Translate this page into:

Defining a Good Death in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review

*Corresponding author: Wasinee Wisesrith, Doctor of Philosophy Program in Nursing Science, Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. sasinee.w@chula.ac.th

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Hafifah I, Wisesrith W, Ua-Kit N, Ho BM. Defining a Good Death in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review. Indian J Palliat Care. doi: 10.25259/IJPC_21_2025

Abstract

Understanding the definition of a good death in the intensive care unit (ICU) is crucial for the effective implementation of end-of-life care. Existing reviews often focus on terminal patients and overlook the ICU setting. This study aimed to investigate the definitions of a good death in the ICU. The systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines and was registered with PROSPERO. The database searched included PubMed, ScienceDirect and EBSCOhost. Inclusion criteria encompassed English-language quantitative or qualitative studies published from inception until August 30, 2024, that reported definitions of a good death in the ICU and were available in full text. Exclusion criteria included studies that focused exclusively on euthanasia. The risk of bias was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for quantitative or qualitative studies, and a narrative synthesis was performed. Definitions were categorised into themes and subthemes, with the frequency of each theme determined from the perspectives of patients, family members and healthcare professionals (HCPs). Thirty-five high-quality studies were included, with 60% of the articles representing family members perspectives. We identified five themes of a good death: Being free from suffering, withdrawing and withholdinglife-sustaining technologies in ICU settings, privacy, family involvement, and receiving spiritual and cultural support. However, discrepancies among the respondent groups were noted in the core themes: Family members emphasised being free from suffering, while patients reported family involvement more frequently. HCPs highlighted the importance of spiritual and cultural support. This review highlights the definitions of a good death in the ICU. These findings can aid HCPs in gaining a better understanding of a good death in the ICU. Future research should focus on determining the factors influencing a good death.

Keywords

Definition

Good death

Intensive care unit

Meaning

INTRODUCTION

End-of-life care (EOLC) in intensive care unit (ICU) settings is a significant concern for healthcare professionals (HCPs) because many patients die in the ICU due to a decline in their condition or a lack of progress despite interventions. The World Health Organisation estimated that there are an additional 1.1 to 7.4 million deaths globally from critical illnesses.[1] Mortality rates vary significantly by region: 35.3% in Africa,[2] 27% in Europe, 29% in the United States[3] and 36.5% in Indonesia in Asia.[4]

A goal of EOLC is to facilitate a ‘good death’ for patients. However, the definition of a good death varies widely due to individual perceptions, beliefs, health condition, place of death and sociocultural contexts.[5,6]

Many previous studies have explored the definition of a good death in patients with chronic illnesses and cancer. However, studies regarding the definition of a good death in the ICU setting are very limited. Although ICUs are designed to care for acutely ill patients, they are not considered to be ideal spaces for dying patients. Patients in the ICU have a short period until death. They experience loss of consciousness, physical discomfort and psychological suffering, often without their families by their side.[5,6] Therefore, what constitutes a good death for those who die in an ICU setting may be somewhat unique to the characteristics of this population and the setting in which they die. Given the increasing number of deaths occurring in the ICU, understanding the components of a good death is a timely and highly practical matter.

The previous studies explain the definition of good death, which is ‘free from avoidable distress and suffering for patient, family and caregivers, in general accord with the patient’s and family’s wishes and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural and ethical standards’. However, experts in psychology, sociology and anthropology have stated that this definition is less comprehensive because it focuses solely on a person’s internal aspects and does not address the external aspects of human beings. Subsequently, the concept related to good death emerged in the term ‘quality of death and dying’, which is ‘the degree to which a person’s preferences for dying and the moment of death agree with observations of how the person actually died, as reported by others’. Far less research, nevertheless, has defined precisely what a decent death is in the eyes of patients, family members and healthcare providers, as opposed to conceptualising it. The objective of this article is to explore the literature that examines what a good death means from the perspectives of patients, their families and HCPs, through a multidimensional lens that encompasses physical, emotional, spiritual and social factors.[1,3-6]

To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review to identify the definition of a good death in the ICU as perceived by patients, family members and healthcare providers. Understanding the meaning of a good death in the ICU from the perception of all groups is important for implementing care for end-of-life patients. The findings of this study are also valuable for future research, particularly in examining the factors that influence a good death in the ICU. This could contribute to enhancing the quality of health care services in the ICU.

METHODS

A systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses - 2020 guidelines was performed.[7] The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024601780).

Search strategy

The search was conducted in PubMed, ScienceDirect and Ebscohost. We did formulate a Population, Intervention or exposure, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) strategy to guide the search process in formulating the research question [Supplementary File 1]. The engaged keywords were settled on medical subject heading terms and the BOOLEAN operator. The search syntax was formed as follows: definition AND good death AND ICU.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria encompassed English-language quantitative or qualitative studies published from inception until August 30, 2024, that reported definitions of a good death in the ICU and were available in full text. Exclusion criteria included studies that focused exclusively on euthanasia.

Selection of studies

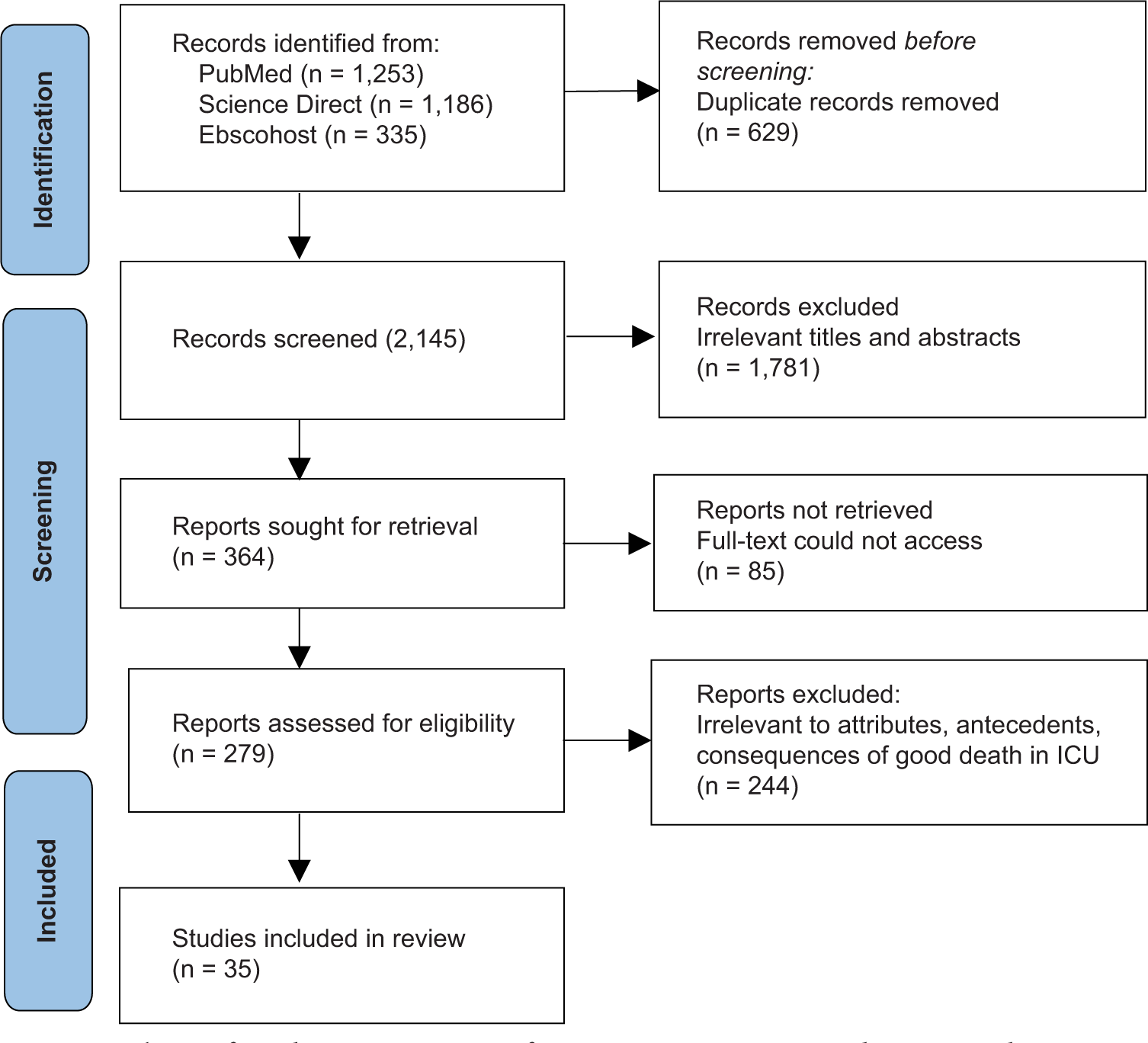

All relevant studies were imported into EndNote 20, and duplicates were removed. One reviewer (IH) conducted the screening process twice and was then independently checked by another reviewer (NU and BM). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion for agreement (WW). Screening involved three steps [Figure 1]: Excluding irrelevant titles and abstracts, searching for full-text articles and reading full-text articles to identify those meeting inclusion criteria. Studies reporting definitions of good death in the ICU were included.

- The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses - 2020 flows diagram of studies included in the review.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in the studies included in our systematic review was assessed by utilising the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for quantitative and qualitative studies[8] in assessing the potential bias in study design, conduct and analysis. Three reviewers (IH, NU and BM) independently evaluated the study quality, resolving discrepancies through discussion. Any unresolved disagreements were arbitrated by a fourth reviewer (WW). To determine the score, the number of ‘yes’ items was divided by the total number of items and multiplied by 100%. Studies scoring over 70% were deemed high quality, those between 50% and 70% were medium quality, and those below 50% were considered low quality. Studies of low quality were excluded from this systematic review.[9] All studies in this systematic review were classified as high quality, as they scored 85% and 90%. None of the studies have scores below 50%; thus, all studies are included in this systematic review. All studies clearly defined the definition of a good death in the ICU. We also accounted for the potential risk of sampling bias in the studies included in our systematic review by geographical region.

Data extraction

An Excel spreadsheet was utilised for data extraction. The sheet contained study details such as author names, publication year, design, location, participants, age, sample size and definition of good death. The data extraction was carried out by IH and cross-checked by NU and BM, with any disparities resolved through discussion (WW).

Data synthesis

After the data extraction, the information was synthesised by a reviewer (IH) to identify the definition of a good death in the ICU, which was then independently validated by another reviewer (NU and BM). In cases of disagreement, discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the reviewing authors. We consulted the third reviewer (WW) if consensus could not be reached.

Due to the heterogeneity of participants across the included studies, a meta-analysis of the data was not conducted. This kind of study was not feasible with our data. In addition, because qualitative and quantitative investigations were mixed, weighting was not done. However, we were able to aggregate frequencies across research to get the mean percentages for various areas of what is thought to be part of a good death, because all studies reported stakeholder frequency of responses that supported particular themes of a good death.

We generated common themes of a good death using the grounded theory-based coding consensus, co-occurrence and comparison method. Our thematic analysis was conducted inductively from the data, meaning that themes were identified directly from the content of the studies, without being guided by a pre-existing framework. This allowed us to stay close to the data and ensure that the themes reflected the experiences and perspectives of the participants in the studies we reviewed. However, we also recognise that existing theories and concepts related to EOLC in ICU settings may have informed the initial stages of analysis.

The process of identifying themes followed the standard procedure for thematic analysis: We first familiarised ourselves with the data by reading and re-reading the studies; initial codes were generated to capture key features of the data related to a good death in ICU settings; as patterns emerged, we grouped related codes into broader themes. These themes were refined through constant comparison and discussion amongst the research team to ensure that they accurately represented the data and captured the diversity of perspectives on a good death; after initial coding and theme identification, we revisited the studies to ensure that the final themes were robust and reflective of the data as a whole. We engaged in several rounds of refinement, checking that the themes were sufficiently inclusive of the different experiences and perspectives presented in the studies. In cases where discrepancies or ambiguities arose, the research team discussed and resolved them to reach consensus on the final themes.

We reported the rate of endorsement of each of the 5 codes within each of the sources (e.g., patients, family members and HCPs) and computed the percentages.

Instead, a narrative synthesis was conducted, following the reporting guidelines of Synthesis Without Meta-analysis [Supplementary File 2].[10] This narrative synthesis aimed to identify and describe patterns within the data, focusing on similarities, differences and associations amongst study outcomes.[11]

The synthesis specifically focused on identifying definitions of a good death in the ICU. To provide a more comprehensive synthesis of the evidence across studies, the identified definitions were categorised. This classification process was informed by previous studies on a good death. These categories included (1) definitions of a good death from the perspectives of patients, (2) definitions of a good death from the perspectives of family members and (3) definitions of a good death from the perspectives of HCPs.

RESULTS

Identification and selection of studies

A total of 2,774 records were identified in the database. After removing 629 duplicate records, we screened the remaining 2,145 records based on their titles and abstracts. Of these, 1,781 reports were excluded due to irrelevant titles and abstracts. We then assessed the full text of 364 studies, eliminating 85 studies. As a result, 279 studies were initially considered. However, upon further evaluation, 244 studies were excluded. Ultimately, 35 studies were included, as summarised in [Figure 1].

Characteristics of included studies

Thirty-five high-quality studies were included. The participants’ mean age ranged from 30.64 to 48.37 years old. The sample size ranged from 30 to 604. The characteristics of included studies are summarised in Figures 2 and 3. They were conducted in various regions, including Indonesia (1 study), Turkey (3 studies), Thailand (4 studies), Iran (6 studies), Korea (5 studies), UK (7 studies) and US (8 studies) [Figures 2 and 3].

- Participant characteristics based on number of studies.

- Study location.

Definitions of a good death in ICU

Definitions were categorised into themes and subthemes, with the frequency of each theme determined from the perspectives of patients, family members and HCPs. The term defines the characteristics that differentiate the phenomenon from a similar one. The relevant resources are used to identify the definition of a good death amongst ICU patients. ‘Being free from sufferings’ was the most supported theme in the literature, followed by the ‘withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings’, ‘privacy’, ‘family involvement’ and ‘receiving spiritual and cultural support’. Therefore, the conceptual definition of good death in ICU arrived at in this study was the condition of dying and death, including being free from sufferings, withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings, privacy, family involvement and having spiritual and cultural support.

Being free from sufferings

Being free from suffering is a vital part of a good death in the ICU. This attribute is free from physical and emotional suffering. The majority of suffering amongst ICU patients is pain.[6,12-17]

Withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings

Life-sustaining technologies, such as mechanical ventilation, dialysis and other interventions, may affect the ability of patients to have a good death. These technologies, while life-saving in many circumstances, can sometimes prolong the dying process and may contribute to discomfort, emotional distress or a perceived loss of autonomy for both patients and their families. This theme includes the earlier cessation of treatment, unnecessary prolongation of life and less visible technology.[18-22]

Privacy

Privacy is a comfortable environment. Patients die in a private room, accompanied by family.[23-27]

Family Involvement

The involvement of the family is crucial in ensuring that the patient dies in a state of good death. This theme includes having an opportunity to say goodbye, participating in important care decisions, patients have chances to say their wishes to families, and patients are not alone while dying. Family members often experience profound grief, stress and a sense of helplessness, which can influence how they interpret the quality of the patient’s death. This includes aspects such as the opportunity for closure, the sense of peace and dignity in the patient’s final moments and the ability to participate in important care decisions.[28-35]

Receiving spiritual and cultural support

Having spiritual and cultural support means patients having spiritual and cultural support from their families or healthcare providers to maintain their behaviours and traditions before death.[36-45] The themes and sub-themes of the definition of a good death in the ICU in [Table 1]. However, discrepancies among the respondent groups were noted in the core themes: family members emphasised being free from suffering, while patients reported family involvement more frequently. Healthcare providers highlighted the importance of spiritual and cultural support. Differences in frequencies of themes amongst the stakeholder groups were greatest for withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings, which was rated more frequently in HCP’s perspective articles (80%) than in patient and family members’ perspective articles (44.44% and 38%, respectively) [Table 2]. The themes of good death in ICU as summarised in [Figure 4].

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| • Being free from sufferings | • Free from physical sufferings, including pain, severe shortness of breath • Free from emotional sufferings, including anxiety |

| • Withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings | • The earlier cessation of treatment • Unnecessary prolongation of life • Less visible technology |

| • Privacy | • Comfortable environment • Private room |

| • Family Involvement | • Having an opportunity to say goodbye • Participate in important decisions regarding care, • Patients have chances to say their wishes to their families • Patients are not alone while dying |

| Receiving spiritual and cultural support | • Spiritual support • Cultural support • Patient’s behaviours and traditions |

ICU: Intensive care unit

| No. of articles on ICU patients (n=9) (%) | No. of articles of family members (n=21) (%) | No. of articles of healthcare professionals (n=5) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Being free from sufferings | 7 (77.78) | 21 (100) | 2 (40) |

| Withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings | 4 (44.44) | 8 (38) | 4 (80) |

| Privacy | 5 (55.55) | 15 (71.43) | 1 (20) |

| Family Involvement | 9 (100) | 18 (85.71) | 4 (80) |

| Receiving spiritual and cultural support | 8 (88.89) | 20 (95.24) | 5 (100) |

ICU: Intensive care unit

- Conceptual model of good death in ICU.

DISCUSSION

We identified several themes defining a good death in the ICU, marking the first systematic exploration of these definitions. These findings offer valuable insights into our current understanding of the definition of a good death in the ICU and provide significant recommendations for clinical practice and future research. We generated common themes of a good death using the grounded theory-based coding consensus, co-occurrence and comparison method. Our thematic analysis was conducted inductively from the data, meaning that themes were identified directly from the content of the studies, without being guided by a preexisting framework. This allowed us to stay close to the data and ensure that the themes reflected the experiences and perspectives of the participants in the studies we reviewed. However, we also recognise that existing theories and concepts related to EOLC in ICU settings may have informed the initial stages of analysis.

Being free from sufferings

The first and most prominent theme that emerged from our data is the desire to be free from suffering, a fundamental aspect of a good death. The physical discomfort associated with terminal illness, often exacerbated in the ICU by invasive procedures and mechanical interventions, remains a major concern for both patients and their families. The ability to alleviate pain and distress, through effective palliative care and symptom management, is a cornerstone of achieving a good death in the ICU setting. This finding aligns with previous studies, which have identified the relief of physical suffering as essential for a dignified and peaceful death.[6,12-17] In addition to physical suffering, emotional and psychological distress are a significant component of the ICU experience, particularly for patients who are nearing the end of life. Patients and families in our study reported the emotional toll of uncertainty, fear and the sense of losing control over the dying process. The constant medical interventions, coupled with the often unpredictable course of critical illness, create an environment that can exacerbate anxiety, sadness and existential distress. A good death, therefore, also involves the mitigation of emotional suffering. Ensuring that patients and families feel informed, supported and heard can significantly alleviate the emotional burden of the dying process. Open and empathetic communication between the healthcare team and the family is critical, as it helps to establish realistic expectations and reduce the fear of the unknown. In this context, the role of the healthcare provider goes beyond medical expertise; it also involves offering emotional reassurance, being present with the patient and family and acknowledging the emotional gravity of the situation.[6,12-17]

Our reviews suggest that emotional suffering is not limited to the patient but extends to family members as well. Family members often experience anticipatory grief, uncertainty and distress about the patient’s suffering, as well as the fear of impending loss. Providing emotional support to families through counselling, clear explanations and allowing for family involvement in decision-making can contribute significantly to reducing their psychological distress and help them feel more equipped to navigate the final stages of the patient’s life.

Withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings

The percentage of occurrence of this theme is highest from the healthcare professionals’ perspective. Life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings, such as mechanical ventilation, dialysis and other interventions, may affect the ability of patients to have a good death. These technologies, while life-saving in many circumstances, can sometimes prolong the dying process and may contribute to discomfort, leading to potential issues such as pain, sedation or feelings of being detached from one’s body, emotional distress or a perceived loss of autonomy for both patients and their families. In addition, the presence of technology can diminish the opportunity for patients to die in a more natural or peaceful setting, potentially altering the emotional and spiritual aspects of death. For families, witnessing a loved one attached to life-sustaining machines can create distress, feelings of helplessness and a complex decision-making environment.[18-22]

HCPs manage the tension between the benefits of life-sustaining technologies and the desire for a good death using effective communication, shared decision-making and palliative care to guide families through difficult choices regarding whether to continue, limit or withdraw treatments. The importance of aligning treatment decisions with the patient’s values and preferences, as well as providing adequate support to families in these emotionally charged situations, will also be emphasised. HCPs must strike a balance between extending life through technological interventions and ensuring that the patient’s quality of life, particularly their comfort and dignity, is maintained during the dying process. This includes recognising when technology may no longer be in the patient’s best interest and considering a shift towards palliative care measures that prioritise symptom management and emotional support.[18-22]

This theme is closely tied to the medical decision-making process and reflects the importance of aligning care with the patient’s prognosis and goals. Many participants in our study highlighted the significance of having treatments discontinued when they were deemed futile or when the burdens of continued intervention outweighed the potential benefits. This theme underscores the tension between medical technology and the preservation of dignity, as the ICU is often perceived as a space where aggressive treatment may be overemphasised at the expense of quality of life. The decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments is fraught with ethical and emotional challenges, yet it remains an essential aspect of ensuring that the death process respects the patient’s wishes and values.[18-22]

Privacy

Privacy emerged as a critical factor in defining a good death, especially given the high-stress, often crowded, nature of ICU environments. Both patients and their families expressed the importance of maintaining dignity and personal space in the final moments of life. The ICU, with its constant monitoring, visits and medical procedures, can be an inhospitable environment for maintaining privacy, particularly in the moments of death. This finding emphasises the need for ICU teams to be mindful of the emotional and psychological impact of surveillance and constant medical presence. Ensuring privacy, even if only in the final hours, provides families with the space to grieve and patients with the sense of autonomy and dignity that they deserve at the end of life. Privacy, in this context, extends beyond physical space, encompassing the ability to have intimate, unimpeded moments with loved ones and to experience the final phase of life in a way that preserves the patient’s personhood.[23-27]

Family involvement

The emotional and psychological needs of family members during the dying process are crucial. The involvement of family members in care decisions can significantly impact the overall experience of death and, consequently, the definition of a good death. The concept of a good death includes not only the patient’s experience but also the relational and emotional aspects that influence how families perceive the good death. HCPs adopt more family-centred approaches in ICU settings to better support family members throughout the dying process. This includes fostering open, empathetic communication, involving families in care decisions and offering psychological and emotional support. By attending to both the patient’s and the family’s needs, healthcare providers can help facilitate a more holistic approach to EOLC that aligns with the goals of a good death for all involved.

The opportunity for patients to say goodbye to their loved ones is another essential aspect of a good death in the ICU, as highlighted by our study participants. The ICU, with its focus on life-saving interventions, often places patients in situations where they may not be able to interact meaningfully with their families before death. This disconnection can lead to a sense of unfinished business, both for patients and their families. Ensuring that patients have the chance to communicate and say farewell to loved ones is an emotional and relational aspect of a good death that contributes to closure and emotional healing. This theme resonates with the broader literature on EOLC, where the importance of family involvement and communication has been identified as a significant contributor to both the quality of death and the grieving process. Allowing family members to witness the final moments and participate in decision-making fosters a sense of shared experience and collective mourning, which can be essential for both emotional closure and family resilience.[28-35]

Receiving spiritual and cultural support

Finally, the theme of spiritual and cultural support highlights the role of belief systems in shaping what constitutes a good death. For many patients and families, the presence of spiritual guidance or the accommodation of cultural practices provides comfort and meaning in the face of terminal illness. In the ICU, where medical care often focuses on the physical body, the need for spiritual care can be overlooked. Our findings suggest that access to chaplaincy services, prayer or cultural rituals can significantly enhance the experience of dying, offering a sense of peace, transcendence and continuity beyond the medicalised environment of the ICU. The importance of spiritual and cultural care has been increasingly recognised in palliative care, with studies emphasising that attending to these needs can improve patient satisfaction, reduce suffering and provide emotional solace to families.[46]

The importance of spiritual and cultural support in EOLC, particularly in ICU settings, where patients may face complex medical decisions and heightened emotional stress. Spiritual and religious beliefs can significantly shape a patient’s and their family’s understanding of a good death, providing comfort, meaning and a sense of peace.[36-45]

Examples of religious and spiritual practices such as Islam: For Muslim patients, spiritual practices such as prayer (Salat), the recitation of the Shahada (testimony of faith) and the presence of a religious leader or imam are essential at the end of life. Christianity: Many Christian patients and families may find comfort in the rituals of prayer, the presence of a chaplain or the administration of sacraments such as communion or anointing of the sick. In ICU settings, patients may desire to receive spiritual support from clergy or family members to affirm their faith and provide peace in their final moments. Hinduism: In Hindu tradition, the concept of death is often viewed as a transition to the next life. Rituals such as chanting mantras, having a priest or family member perform specific prayers, and the idea of a proper ritual for the body (such as bathing and anointing the body) are key aspects of a good death. In the ICU, family members may focus on ensuring that the patient’s body is treated with respect, often requesting the opportunity to perform or witness these rituals. Buddhism: Buddhist patients may emphasise the importance of mindfulness, meditation and the presence of a spiritual leader (monk or teacher) to guide them through the process of dying. Indigenous Spiritual Practices: For patients from Indigenous cultural backgrounds, the concept of death is often deeply connected to family, community and ancestral spirits. Spiritual rituals may include ceremonies that honour the deceased, such as smudging, prayer or offerings to spirits. In ICU settings, family members may request space for these rituals to be performed, and the presence of family and community can play a significant role in how the dying process is viewed.[36-45]

In addition, cultural context influences the ICU experience and the definition of a good death. Death rituals and practices vary significantly across cultures, and these differences can shape how a ‘good death’ is perceived in ICU settings. For instance, in some cultures, death is viewed as a transition to the afterlife that requires specific rituals or spiritual practices. For example, in many Asian cultures, the family may place great emphasis on preparing the deceased’s body and performing rites that ensure a peaceful transition. In contrast, some Western cultures may focus more on medical interventions aimed at sustaining life, sometimes at the cost of delaying the natural process of death. These cultural variations can influence not only the family’s expectations of a good death but also the care decisions made in the ICU.[36-45] Family involvement in the decision-making process at the end of life is another aspect influenced by cultural context. In some cultures, especially in many Asian, African and Latin American communities, family decision-making is a collective process, with the extended family often playing a significant role. This contrasts with more individualistic cultural perspectives, such as in some Western societies, where the patient’s autonomy and individual wishes may be prioritised. In ICU settings, the family’s role in deciding whether to continue life-sustaining treatments or transition to palliative care can be influenced by cultural norms around family structure, authority and responsibility. This may impact the perceived quality of death for both the patient and the family, as certain cultural expectations around family involvement may either ease or complicate the decision-making process.[36-45]

Furthermore, the role of spirituality and religion in defining a good death is deeply influenced by cultural context. For example, in many Christian cultures, spiritual practices such as prayer, the presence of a chaplain and rituals like communion or anointing the sick are integral to the experience of dying. In contrast, Hindu or Buddhist patients may seek guidance from spiritual leaders and engage in rituals that facilitate a peaceful transition to the afterlife, such as meditation or chanting mantras. Similarly, Islamic patients may focus on specific prayers, such as the recitation of the Shahada, or request the presence of an imam. Cultural differences in spiritual practices can influence both how families and patients experience the ICU environment and how they define a good death.[36-45]

The varying cultural expectations and practices can significantly affect how patients and families experience death in ICU settings. In cultures where death rituals are highly significant, the inability to perform these rituals in the ICU – due to technological constraints or time limitations can create emotional distress and contribute to the feeling of an incomplete or unsatisfactory death. In addition, cultural expectations surrounding family involvement in decision-making can create tensions if healthcare providers are not sensitive to these dynamics. For example, in cultures where family members expect to be deeply involved in care decisions, excluding them from discussions or making decisions without their input can result in a sense of alienation and dissatisfaction with the dying process. To better support patients and families from diverse cultural backgrounds, HCPs must be trained in cultural competence and sensitivity. Understanding and respecting cultural differences in death rituals, family involvement and spiritual practices can help ensure that the dying process is handled in a way that aligns with the values and needs of the patient and their family. In ICU settings, where care is often highly medicalised, incorporating cultural and spiritual practices into care plans can help facilitate a more holistic, meaningful and peaceful death experience.[36-45]

Strengths

To our knowledge, it is the first review to investigate the definitions of a good death in ICU. A comprehensive understanding of the definition of a good death in the ICU is crucial for nurses to improve EOLC for patients.

Limitations

The limitation of this study is the heterogeneity of the included studies, particularly in terms of study populations and methodologies. While this diversity provides a broad perspective, it also presents challenges in synthesising the findings and drawing generalised conclusions. We address this by acknowledging the limitations in the generalisability of the results and suggest that future studies explore more homogeneous populations for more specific insights.

Implications

This study highlights the importance of cultural competence in ICU settings, suggesting that healthcare providers need to be more attuned to the diverse religious, cultural and emotional needs of both patients and families. By incorporating culturally sensitive care into end-of-life planning, HCPs can facilitate a more positive and individualised experience of death. In addition, the findings suggest a need for policies that support the inclusion of spiritual and cultural practices in EOLC protocols in ICU settings. This would ensure that patients and families have the necessary support to navigate the emotional and spiritual aspects of dying, in addition to the medical aspects. Healthcare systems may benefit from the integration of chaplaincy services, cultural liaisons and other support systems in ICU care. Furthermore, future studies should explore more homogeneous populations for more specific insights.

Recommendations

We recommend that ICU care teams adopt a more family-centred care approach in end-of-life situations. This includes involving families in decision-making and ensuring that their emotional, psychological and spiritual needs are addressed alongside the patient’s medical needs. Furthermore, we recommend that healthcare providers receive training in cultural competence. This training should focus on understanding diverse cultural attitudes towards death and the rituals and practices that accompany the dying process. In addition, to increase the generalisability of findings, we recommend expanding research on ICU EOLC to diverse populations, particularly in low-income and non-Western countries. This would provide a broader understanding of how different cultural, social and economic factors influence the definition of a good death.

CONCLUSION

This review identified themes associated with the definitions of a good death, including being free from sufferings, withdrawing and withholding of life-sustaining technologies in ICU settings, privacy, family involvement and receiving spiritual and cultural support. Nurses’ understanding of the true definition of a ‘good death’ in ICU patients is crucial. This understanding can enhance nursing performance in EOLC. Furthermore, future research should explore more homogeneous populations for more specific insights and investigate the factors that influence a good death in ICU patients. These factors could potentially be modified by nurses or nursing managers to improve EOLC and ensure that patients experience a good death.

Acknowledgements:

This paper is part of the dissertation of Mrs. Ifa Hafifah, a Ph.D. Candidate entitled ‘A Path Analysis of Good Death as Perceived by Muslim Nurses Caring for End-of-Life Patients at Intensive Care Unit in Indonesia’. The Ph.D. programme was funded by the Graduate Scholarship Programme for ASEAN and Non-ASEAN Countries. Recipient: Ifa Hafifah.

Ethical approval:

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent:

Patient’s consent is not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation:

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- What is a Good Death? Health Care Professionals' Narrations on End-of-Life Care. Death Stud. 2014;38:20-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing (6th ed). New York: Pearson; 2019. p. :167-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- What are the Challenges for Nurses when Providing End-of-Life Care in Intensive Care Units? Br J Nurs. 2019;28:1047-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- “But Isn't it Depressing?” The Vitality of Palliative Care. J Palliat Care. 2002;18:15-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- End-of-Life Care: Improving Quality of Life at the end of Life. Prof Case Manag. 2007;12:339-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What is an Intensive Care Unit? A Report of the Task Force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. J Crit Care. 2017;37:270-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. South Australia: JBI; 2020. Ch. 7 Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 10]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Effect of Advance care Planning Intervention on Hospitalization among Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23:1448-60.e1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) in Systematic Reviews: Reporting Guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Crit Care. 2006;25:438.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors that Affect Quality of Dying and Death in Terminal Cancer Patients on Inpatient Palliative Care Units: Perspectives of Bereaved Family Caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:735-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John and Mary Q. Public's Perceptions of a Good Death and Assisted Suicide. Issues Interdiscip Care. 2001;3:137-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- How do Critical Care Nurses Define a “Good Death” in the Intensive Care Unit? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2010;33:87-99.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICU Nurses' Perceptions and Practice of Spiritual Care at the End of Life: Implications for Policy Change. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016;21:6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intensive Care and Oncology Nurses'Perceptions and Experiences With futile Medical Care and principles of Good Death. Turk J Geriatr/Türk Geriatr Derg. 2017;20:116-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is Dying in Hospital Better than Home in Incurable Cancer and what Factors Influence This? A Population-Based Study. BMC Med. 2015;13:235.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How do Intensive Care Clinicians Ensure Culturally Sensitive Care for Family Members at the end of Life? A Retrospective Descriptive Study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2022;73:103303.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A “Good Death”: Perspectives of Muslim Patients and Health Care Providers. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:215-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions of a Good Death: A Qualitative Study in Intensive Care Units in England and Israel. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2016;36:8-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 'Viewing in Slow Motion': Patients', Families', Nurses' and Doctors' Perspectives on End-of-Life Care in Critical Care. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:1442-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- No Time for Dying: A Study of the Care of Dying Patients in two Acute Care Australian Hospitals. J Palliative Care. 2003;19:77-86.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Relationships among Palliative Care, Ethical Climate, Empowerment, and Moral Distress in Intensive Care Unit Nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2018;27:295-302.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Related Factors to End of Life Care by Nurse in Intensive Care Unit. J Aisyah J Ilmu Kesehatan. 2021;6:93-100.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intensive Care Nurses' Attitude on Palliative and End of Life Care. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21:655-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives of Physicians and Nurses Regarding End-of-Life Care in the Intensive Care Unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27:45-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Professionals' Values About and Experience with Facilitating End-of-Life Care in the Adult Intensive Care Unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;65:103057.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICU Nurses' Experiences in Providing Terminal Care. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2010;33:273-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurses' Perceptions of Intensive Care Unit Palliative Care at End of Life. Nurs Crit Care. 2019;24:141-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Care Nurses' Attitude Towards Life-Sustaining Treatments in South East Iran. World J Emerg Med. 2016;7:59-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- End-of-Life Care (EOLC) in Jordanian Critical Care Units: Barriers and Strategies for Improving. Crit Care Shock. 2019;22:88-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preferences for End-of-Life Care and Decision Making among Older and Seriously Ill Inpatients: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59:187-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of the Awareness of a Good Death and Perceptions of Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions on Attitudes of Intensive Care Nurses Toward Terminal Care. J Korean Crit Care Nurs. 2019;12:39-49.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Good Death Inventory: A Measure for Evaluating Good Death from the Bereaved Family Member's Perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:486-98.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): Empirical Domains and Theoretical Perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:9-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Validation of a New Measure of Concept of a Good Death. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:575-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difficulties Perceived by ICU Nurses Providing End-of-Life Care: A Qualitative Study. Glob Adv Health Med. 2020;9:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patients Versus Healthcare Providers' Perceptions of Quality of Care. Establishing the Gaps for Policy Action. Clin Gov Int J. 2015;20:170-82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Described Nursing Roles Experienced During Care of Dying Patients and their Families: A Phenomenological Study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30:211-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse-Rated Good Death of Chinese Terminally ill Patients with Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28:e13147.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coping with Moral Distress-The Experiences of Intensive Care Nurses: An Interpretive Descriptive Study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;53:23-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of Palliative Care in Intensive Care Unit “X” Hospital Indonesia. Enfermeria Clinica. 2020;30:16-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Concept of a Good Death from the Perspectives of Nurses Caring for Patients Diagnosed with COVID-19 in Intensive Care Unit. Omega (Westport) 2023:1-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How Intensive Care Nurses Perceive Good Death. Death Stud. 2018;42:667-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors Associated with Good Death of Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Prospective Study in Japan. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:9577-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care: The Report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;10:885-904.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]