Translate this page into:

Early Referral to Palliative Care for Advanced Oral Cancer Patients: A Quality Improvement Initiative in Oncology Center at All India Institute of Medical Sciences

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Satija A, Lorenz K, DeNatale M, Mickelsen J, Deo SV, Bhatnagar S. Early referral to palliative care for advanced oral cancer patients: A quality improvement initiative in oncology center at All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Indian J Palliat Care 2021;27(2):230-4.

Abstract

Objectives:

Oral cancers have high epidemiologic burden in India, and most oral cancer patients at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences present in advanced stages. Their symptomatic needs are often not adequately addressed and the referrals to palliative medicine clinic are for severe pain or terminal stages. Using quality improvement methods, we aimed to provide early referral to palliative care for advanced oral cancer patients.

Materials and Methods:

Duration (number of days) between registration at the head-and-neck cancer clinic and referral to palliative medicine clinic at baseline and postinterventions. Interventions: Understanding current perceptions of oncologists for referral to palliative medicine clinic, educating them through departmental meetings, fostering clinician and patient-family awareness through pamphlets, defining process and screening guidelines for referral, including symptom burden charts in head-and-neck cancer clinic notes, soliciting regular feedback from oncologists at review meetings.

Results:

The number of days for the referral to the palliative medicine clinic decreased from an average of 48 days to 13 days in 6 months.

Conclusion:

A multicomponent intervention included oncologists and patients and families, education, workflow modification, standardized assessment, documentation, and clinician feedback, and succeeded in improving the timeliness of palliative care referrals of advanced oral cancer patients.

Keywords

Advanced oral cancer

Early referral

India

Palliative care

Quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

With one-sixth of the global population dwelling in India, it is undergoing an epidemiological shift from high prevalence of infectious diseases to the increasing burden of chronic noncommunicable life-threatening diseases.[1,2] According to the serious health suffering (SHS) database released by International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care and Lancet commission on global access to palliative care and pain relief, approximately 18% out of total 7.27 million Indians experiencing SHS are suffering with cancer.[3] In low-and middle-income countries, approximately 70% of cancer patients are diagnosed at advanced stage which further predisposes them to symptomatic distress, hence, dictating the need to provide them palliative care service.[4] Early integration of palliative care in cancer trajectory may improve symptom control, quality of life and facilitate treatment decisions at end-of-life.[5] While the benefits of early access to palliative care are acknowledged, there are many challenges for its integration into oncology care, such as lack of physician awareness, resource constraints, patients’ reluctance, nonavailability of standard assessment tools, and regulatory barriers.[6,7] Quality improvement (QI) approaches offer efficient, effective, and safe measures to augment patient-centered care while optimally utilizing the resources, skills, and expertise.[8] Ever-increasing burden of cancers and demand for palliative care paves the way for utilizing QI methods in oncology settings as well.[9]

In this report, we describe our experience at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) of using QI methodology[10] to foster early referral of advanced oral cancer patients to palliative care.

Problem Statement

Oral cancers represent nearly 30% of all cancers in India.[11] Poverty, illiteracy, poor health care access, and limited treatment infrastructure pose treatment challenges, and most patients present with advanced disease when the chances of cure and survival are low.[12,13] Many Indian oral cancer patients may benefit from palliative care, but referrals for palliative care are typically delayed until the onset of severe pain or terminal stages. In such late stages and burdened by severe suffering, patients and families fail to benefit fully from palliative care. Relationship and communication with oncologists and surgeons is key to appropriate referral, but physicians struggle to understand palliative care needs and communicate effectively.[7]

At AIIMS, we noted erratic referrals of advanced oral cancer patients for palliative care. India’s vast unmet need for palliative care and growing burden of oral cancers underscored the importance of our focus on developing and implementing processes for early integration of palliative care in this group.

Measures

We undertook our QI project as part of the Palliative Care – Promoting Access and International Cancer Experience in India Collaborative project, a multi-site international collaborative to improve access to and the quality of palliative care in India. It included a consortium of the six United States and Australian university-based palliative care programs and seven Indian major academic palliative care centers, and focused on building organizational capacity for improvement through education and mentored QI projects.[14]

Our AIIMS-based QI team included head-and-neck oncologists, cancer surgeons, palliative care physicians, a research officer, and administrative staff. The AIIMS QI team worked closely with and was regularly coached by QI educators and clinicians (MD, KL, JM) from Stanford University through all stages of our project. The guidance enabled to systematically address the problem and find a sustainable solution. We obtained ethical approval from both the Stanford University Institution review board (IRB-42633) and the Institute Ethics Committee of the AIIMS (IEC-572/03/11.2017, RP-41/2017).

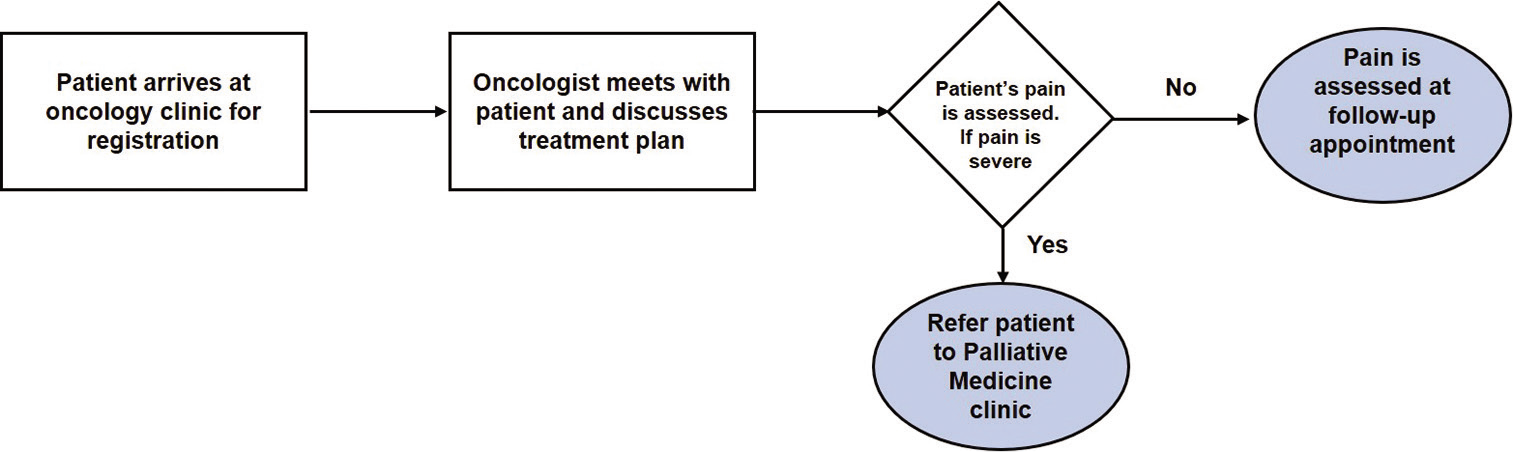

We undertook our project in the outpatient clinic settings of a tertiary cancer care hospital, the Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, AIIMS, New Delhi. To understand referral patterns, we studied the problem to identify the process of patient inter-departmental flow. According to the initial process map, the patient arrived at the oncology clinic for registration. The oncologist, then, met the patient and discussed the treatment plan. Only if patient complained of severe pain, then she/he was referred to palliative medicine clinic else pain was assessed at follow-up visits [Figure 1].

- Initial process map

We also prospectively reviewed the medical records of advanced oral cancer patients referred to the palliative medicine clinic from December 1, 2017, to January 31, 2018. In addition to reviewing their records, we asked patients about the referring department, the reason for referral, symptomatic needs, and perceived reasons for delay in contacting palliative care services.

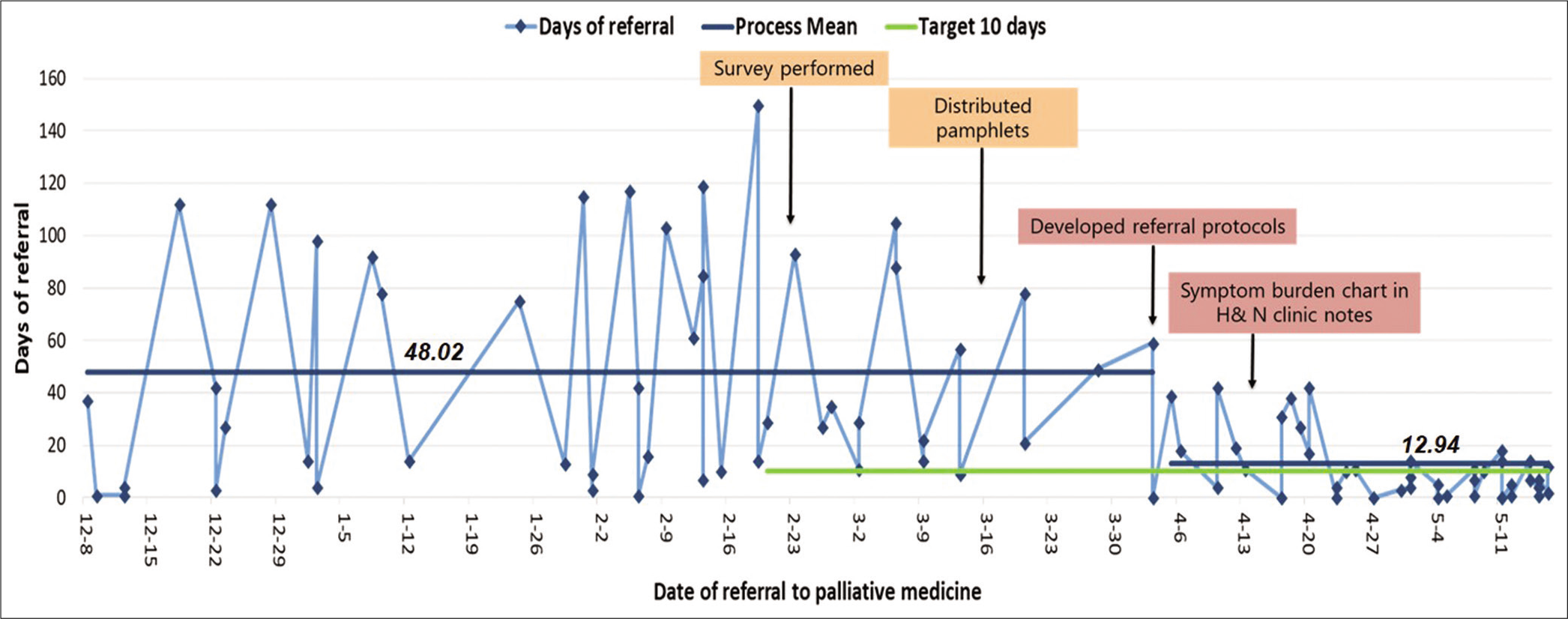

For each case, we characterized the number of days between registration at the head-and-neck cancer clinic and referral to palliative medicine clinic. This data informed baseline metrics and our SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goals. The baseline average time between registration at the head-and-neck cancer clinic and referral to palliative medicine clinic was 48 days and patients reported that oncologists and cancer surgeons were often unaware of their symptomatic needs. We set a goal of reducing the average time between registration at the head-and-neck cancer clinic and referral to palliative medicine clinic from 48 to 10 days.

To understand causes for delays for palliative care referrals, the QI team used observation, for example, Gemba walks[15] and stakeholder group input to perform a cause and effect analysis using the categories of an Ishikawa diagram.[16] The causes were categorized as below:

-

Environment

Cultural understanding of early referral and symptom management by team

Absence of signboards

-

Referring oncologist

Primary focus on cancer treatment versus symptom management

Do not recognize needs other than pain

Methods – No standard guidelines for screening symptomatic needs

Measurement – No standard tool/measure for screening symptomatic needs

Materials – Absence of symptom burden chart in medical records

-

Registered nurses

Involvement triggered when patient is admitted to ward

Actions geared toward patient urgent needs rather than symptoms

Reflecting in-depth on the cause and effect diagram, the QI team decided to focus on addressing the barriers associated with cancer surgeons’ and oncologists’ practice, as they dominate decisions regarding clinical management in our hospital. To understand the problem better and identify effective interventions an online survey was conducted among oncologists and cancer surgeons to understand their current perceptions about palliative care. Majority of physicians agreed that they paid attention to patient’s symptoms. The biggest challenges perceived by them for palliative care referral were inadequate communication with patients and time constraints. The most common reason provided by them for referring advanced oral cancer patients to palliative medicine clinic was pain followed by discussing end-of-life care and psychological support. A vast majority of them believed that early referral to palliative care might be beneficial to this group of patients, and stated that standard screening guidelines/referral protocols were absent.

We listed barriers to the earlier referral on an impact-effort 2 × 2 matrix (e.g. high/low impact X high/low effort) to prioritize barriers (e.g. identify those with the highest impact and lowest effort).[17] The impact-effort analysis revealed that targeting oncologists and developing screening guidelines for patients may have considerable effect on the outcome. We adopted these as “key drivers,” thus focusing on them as our main targets for intervention.

The team identified four key drivers for this project - (a) awareness of medical staff about palliative care consult team, roles, and processes, (b) workflow for palliative care referral and consultation, (c) timeframe for referral to palliative care specialist, and (d) feedback regarding referral duration and patients’ outcomes. Relevant interventions were designed and tested by the project team to achieve subgoals or key drivers.

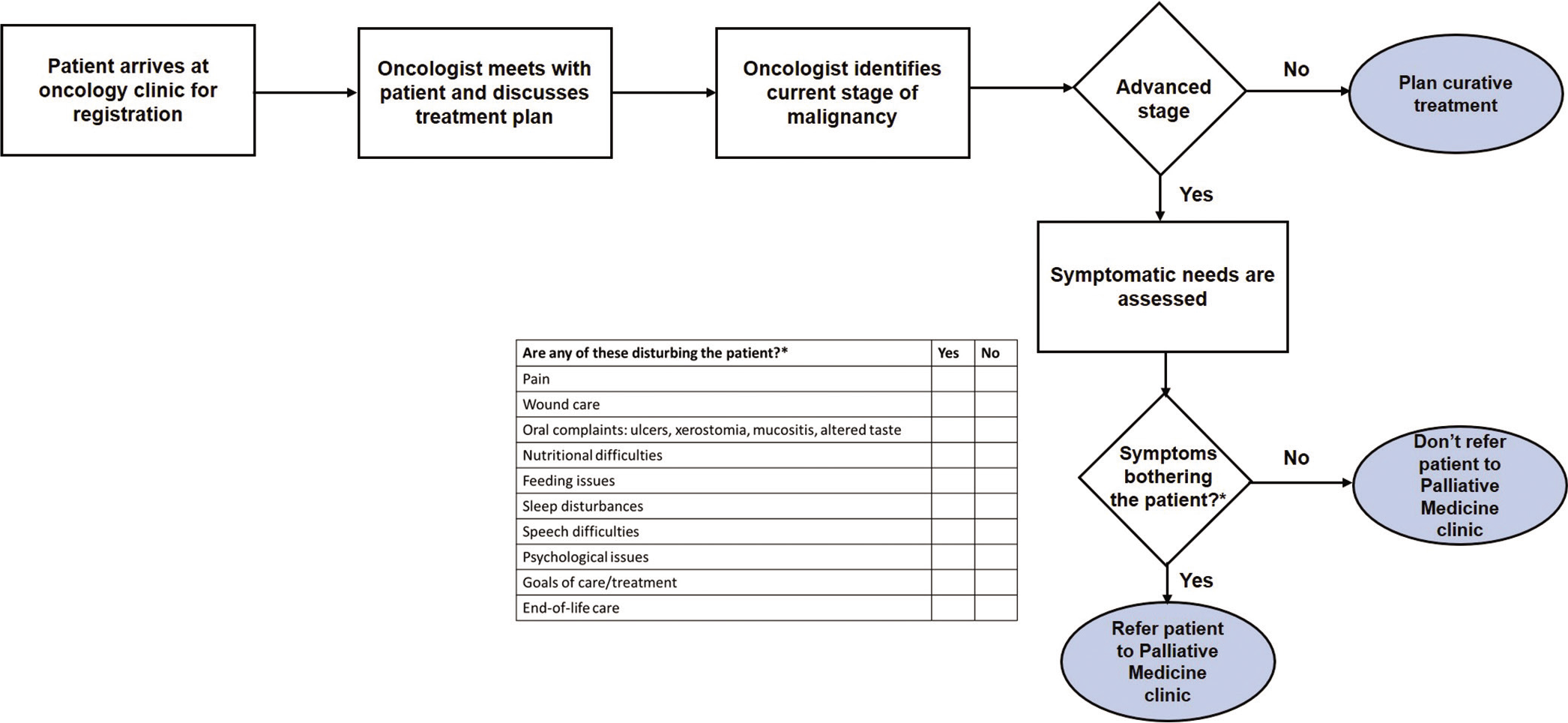

Interventions

Interventions were planned based on the survey findings. Interdepartmental meetings were scheduled every week to address perceptions of oncologists and surgeons and clear their misunderstandings. Pamphlets were designed and distributed to create awareness among them. The project team used to meet frequently and based on the feedback of oncologists and surgeons and clinical expertise of leaders; referral protocols were developed. Due to time constraints, oncologists found it difficult to assess the symptomatic needs of the patients. Hence, a simple checklist symptom burden chart was designed and included in the “head and neck cancer clinic” patient record. If patient reported any one or combination of symptoms/concerns, oncologist and/or surgeon would refer him/her to palliative medicine clinic. The concerns/complaints were documented in a binary format by the oncologist/ surgeon through the question - “Are any of these disturbing your patient? (1) Pain, (2) Wound care, (3) Oral complaints: ulcers, xerostomia, mucositis, or altered taste, (4) Nutritional difficulties, (5) Feeding issues (6) Sleep disturbances, (7) Speech difficulties, (8) Psychological issues, (9) Goals of care or treatment, and (10) End-of-life care.”

A proforma was developed to record the referral practices and document the time duration to referral. The referring oncologists and surgeons were provided a feedback regarding referral duration and patients outcomes through periodic department meetings.

Outcomes

With the implementation of the interventions, the process for referring patient to palliative medicine clinic was modified and followed by oncologists and surgeons. According to the new process map, they would identify the stage of malignancy of patients, assess patients’ symptomatic needs, and refer them to palliative medicine clinic [Figure 2]. Referral duration was observed for 90 patients from December 2017 to May 2018. An annotated control chart was developed to depict the changes in referral duration from baseline to implementation of four specific interventions [Figure 3]. In the preintervention phase, i.e. from December 2017 to February 2018, the average referral duration was 48.02 days. The survey was conducted in the beginning of March 2018. After 2 weeks, the pamphlets were distributed to oncologists. Yet, no significant change in the referral duration was observed. By the beginning of April 2018, a protocol for referring patient to palliative care was ready and after the next 2 weeks, the symptom burden chart was made a part of patient’s medical record. After implementing the last two interventions, the average days to referral decreased to 12.94 days by mid-May 2018.

- New process map

- Days of referral for advanced oral cancer patients to palliative medicine clinic

CONCLUSION

This study has demonstrated a simple and systematic approach for QI in palliative care settings. With the use of QI tools such as Gemba walk and process map, the reasons for delay in referral to palliative care could be identified. Targeting the interventions with high impact and low effort helped in achieving our SMART goal. By implementing QI tools, we decreased the referral duration for advanced oral cancer patients from oncology to palliative medicine clinic from an average of 48 days to 13 days. We qualitatively observed a marked change in practice after the referral protocol was implemented and completing the symptom burden chart became a routine process for the oncologist and cancer surgeon. To sustain our success, we are educating new oncologists and cancer surgeons about referral protocols during upcoming quarterly orientation programs and continue monthly interdepartmental meetings that will focus on auditing patient referral data. In the future, we hope to collect outcomes from both patients and physicians to evaluate the effectiveness of our interventions and use this to continue modifying our approach if needed. We hope to evaluate whether similar interventions may foster more timely palliative care for breast, gastrointestinal, and other malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This QI project was supported by the International Innovation Grant from Conquer Cancer, the American Society of Clinical Oncology foundation.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Palliative care for cancer: A public health challenge in India. Arch Community Med Public Health. 2017;3:54-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- History of the growing burden of cancer in India: From antiquity to the 21st century. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Data Platform to Calculate SHS and Palliative Care Need. Available from: https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/resources/global-data-platform-to-calculate-shs-and-palliative-care-need/database/ [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenges on the provision of palliative care for patients with cancer in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19:55.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Early integration of palliative and supportive care in the cancer continuum: Challenges and opportunities. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013;33:144-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Early integration of palliative care into oncology: Evidence, challenges and barriers. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:122-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of early palliative care in advanced head-and-neck cancers patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25:153-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delivering quality healthcare in India: Beginning of improvement journey. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:735-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers and facilitators of using quality improvement to foster locally initiated innovation in palliative care services in India. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:366-73.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A3 process: A pragmatic problem-solving technique for process improvement in health care. J Health Manag. 2012;14:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Challenges of the oral cancer burden in India. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;2012:701932.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Low survival rates of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dent. 2017;2017:5815493.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Locally advanced oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Barriers related to effective treatment. South Asian J Cancer. 2015;4:61-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The palliative care-Promoting assessment and improvement of the cancer experience (PC-PAICE) project: A multi-site international quality improvement collaborative. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61:190-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Value stream mapping to reduce the lead-time of a product development process. Int J Prod Econ. 2015;160:202-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The analysis of causes and effects of a phenomenon by means of the fishbone diagram. Ann Econ Ser. 2017;5:97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Problem Solving for Success Handbook: Solve the Problem - Sustain the Solution - Celebrate Success (2nd ed). Florida: Value Generation Partners LLC; 2016.

- [Google Scholar]