Translate this page into:

End-of-life Characteristics of the Elderly: An Assessment of Home-based Palliative Services in Two Panchayats of Kerala

Address for correspondence: Ms. Jayalakshmi Rajeev; E-mail: jrajeev.lakshmi1@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Home-based palliative services form the cornerstone of Kerala's palliative program. However, two issues need research: (a) whether family-homes can be considered as the locus of ageing and dying for marginal populations who experience deprivation and poverty and (b) whether the present delivery structure meets the needs of elderly population. These issues are examined in the context of two rural areas. The study explores end-of-life characteristics of the elderly – their sociodemographic status and living patterns, morbidity profile, and functional status. It also looks into the accessibility and utilization of palliative services and respondents’ satisfaction with different components of the services.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive cross-sectional survey design is used. Data were collected based on the interviews of sixty service users sampled randomly from a roster of palliative care services. Semi-structured interviews were substantiated by personal field observations.

Results:

The study has found people living under extreme financial distress with inadequate shelter and poor social security provisions. The health profile is characterized by high level of functional dependence. Many dependent widowed women were living alone without appropriate care and shelter. The palliative program as perceived by the respondents is characterized by few doctor visitations and poor frequency.

Conclusion:

The study concludes that home-based palliation in its present form does not promote good end-of-life care. It lacks an integrated approach with good service-mix. It raises serious questions on family-home as the locus of ageing and dying for marginal populations, and suggests need for restructuring of the palliative program.

Keywords

Elderly

End-of-life characteristics

Family homes

Palliation

INTRODUCTION

The ageing population in India is often overlooked by policy makers in the interest of reaping the benefits of a demographic dividend involving a younger cohort. With India spending a mere 0.032% of its GDP on senior citizens, the elderly population is subjected to neglect and isolation.[1] Presently, India has 100 million elderly; by 2050, this figure is likely to triple to 324 million.[23] The oldest old, those 80 plus, are estimated to reach 48 million by 2050.[1] Different studies and reports prove that the elderly in India suffer from serious ailments, poor physical mobility, and disability.[245]

Context

Given such a dismal picture, palliative home-based care is likely to be a suitable model to serve the needs of elderly experiencing chronicity and functional decline.[6] However, palliative and end-of-life care is still not fully developed in all states of India. It is mostly cancer-specific and developments in geriatric palliative care (PC) are rather small. Two issues assume importance to end-of-life care for elderly: (a) whether family-homes can be considered as the locus of ageing and dying for marginal populations who experience a life-course of deprivation and poverty and (b) whether palliative service in its present delivery structure meets the needs of those who are ageing and dying? These issues are addressed in the context of two gram panchayats in Kerala served by home-based palliative services. The state has a statistically significant proportion of older persons (60 years and above). According to the 2011 census, Kerala accommodates 4 million elderly people. The state is also graying faster than any other state in the country with a life expectancy of more than 71 years.[7] According to Rajan and Misra, it has been adding one million to the elderly population every successive year since 1981. The 80-plus population of Kerala has increased by 0.1 million every census year since 1981 until 2001, and in 2011, the figure stood at 0.2 million.[8] While Kerala's socioeconomic development indicators are far ahead of other Indian states, the epidemiological challenges are also significantly high with prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and cancer.[91011] Moreover, the proportion of elderly reporting their health as poor is as high as 37%, which is the highest among all Indian states in 2004. This indicates that although life expectancy has improved, it has not been accompanied by good quality of life.[12]

As far as palliative services are concerned, Kerala has been the first state in India to take initiative in this direction with community support in Calicut, which was followed by a formal initiative to develop a neighborhood network in PC in Malappuram in 2001.[13] The “Kerala model” in PC envisages a close dialog and interaction with the state and civil society organizations with the formulation in 2008 of a Kerala Palliative Care Policy. The National Rural Health Mission (from 2005 onward), also called Arogya Keralam, in the state has been involved in PC activities since 2007 with the help of Local Self Government Institutions called panchayats. These, along with community-based organizations and government hospitals, including primary health centers (PHCs), facilitate home care projects linked with neighborhood networks for integrated services in PC.[14]

Aims

The study primarily aims at understanding the characteristics of ageing and dying in two rural areas served by gram panchayats in Thiruvananthapuram district of Kerala. It also aims at analyzing to what extent home-based PC services cater to the needs of the elderly residing in resource poor areas.

Settings and design

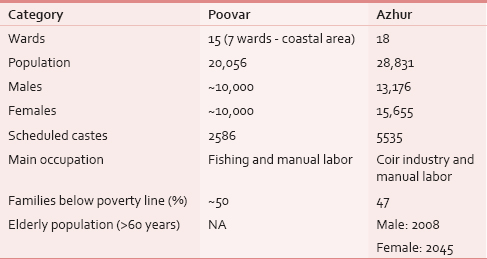

The study focuses on primary level PC services in Poovar and Azhur gram panchayats. Both government and a nongovernmental organization (NGO) with considerable expertise in PC have been serving this region for more than 5 years. The nature of palliation provided is mainly clinical in nature, except for occasional food kits supplied by the NGO. Social security and welfare schemes for the community are meagre, amounting to an irregular sum of INR 750/month, only. The sociodemographic profile of the two panchayats is shown in Table 1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study adopts both quantitative and qualitative methods for data collection. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the researcher among elderly patients and family caregivers. The duration of field work was 2 months. Sixty elderly patients from both panchayats were sampled randomly from a roster of PC services available from government and the NGO working in the area. The researcher interviewed participants at their home accompanied by either the PC nurse or the volunteer of the respective areas. The morbidity status was obtained from the case sheets available at the PHC/NGO, and physical mobility status was ascertained from relatives and through observation during home visits. Qualitative information on physical, mental, and socioeconomic complexities of ageing was recorded in vernacular language using semi-structured interview schedules. Qualitative information was coded during analysis under different themes such as loneliness, faith in supreme power, and anxiety about future, care, and support from family.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

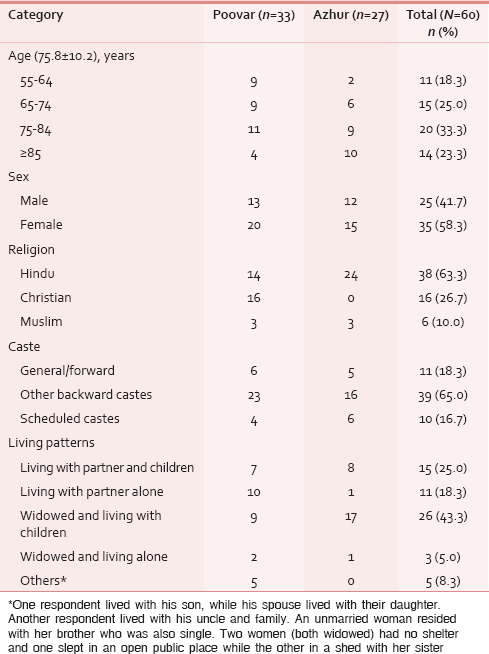

Table 2 depicts the sociodemographic characteristics of study participants in two panchayats – Poovar and Azhur.

As evident from Table 2, the study areas have a multi-ethnic composition belonging to marginal groupings. The number of older-olds is very high in the study sample. About 23% (26) of study participants were above 80 years and among them 14 were females and 12 males, highlighting the present feminization of the elderly. About 51.7% (31) of study participants were widowed and among them 24 were females and the rest males. The living pattern shows that 43.3% were widowed and lived with children, while 5% lived alone. Findings on family status showed that about 50% of the patients are poor (30) and among them, 13 (21.7%) patients and their families lived in extreme deprivation, sometimes even without food. Out of 60, three (5.0%) had no one to take care of them. One elderly still worked for livelihood, as children did not support her. About 70% of the participants reported that they depend on children for their financial requirements. The morbidity profile of the aged is illustrated in Table 3.

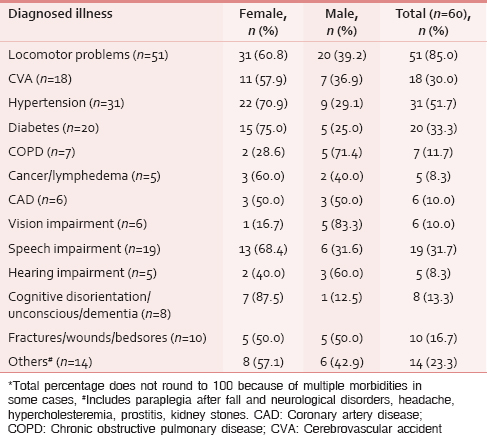

It is evident from Table 3 that the major issue of the elderly is restricted functional mobility. The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and stroke is almost two times higher among women as compared to men. Widowed female participants in the study reported that they overlooked many health issues due to either financial insecurity of the family or lack of care. Speech impairment is a major concern, and the field investigator could not comprehend words correctly many times. Table 4 depicts the functional dependence and duration of illness of respondents.

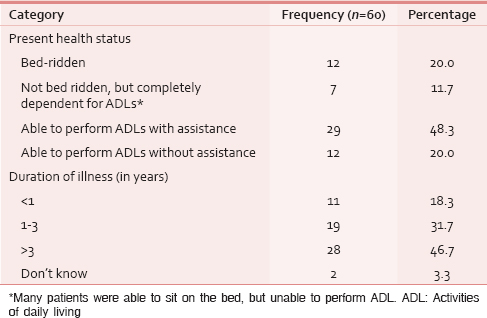

Many patients were able to sit on the bed, but unable to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). Table 4 illustrates the high level of functional dependence of the population with 20% being bed-ridden and 48.3% needing assistance with ADLs. A further fragmentation of data by gender shows that nearly 46.0% (11) of widowed women were completely dependent and three of them were living alone without any one to take care of. Most of the men were partially dependent (64.0%). Nearly half of the study participants (46.7%) were suffering from chronic illnesses for more than 3 years and 31.7% for 1–3 years. All patients suffered from multiple morbidities. However, risk avoidance behavior was rather poor; two patients were compulsive smokers, despite one of them suffering from coronary artery disease and the other from stroke.

Further investigations into the health status of the elderly found that ten patients had to void and defecate on bed itself. Five used bedpans or modified chairs for the same purpose; others could use toilets with or without support. Nine patients had urinary catheters. Two were reluctant to take food or medicines and eight patients suffered from appetite loss. One patient had Ryle's tube for feeding after having undergone surgical treatment of esophageal cancer and she was managing this on her own. Another appeared severely emaciated and was found to be surviving on biscuits only.

Two patients had symptoms of paranoia and abusive behavior: One of them was disoriented and bedridden (rarely opened eyes), while the other was physically healthy, but reluctant and angry all the time, especially on meeting visitors. One woman was suffering from hallucinations and said, “There are worms under my nails.” About eight patients (13.3%) were unconscious, demented, or disoriented. One made occasional cries of “amma, aah;” another kept her eyes tightly shut and opened them for a split of second only when cajoled. Both of them were women. Five patients, who were otherwise well oriented, were not willing to speak to strangers at all. Most of them spent their time watching TV or simply sleeping because of restricted mobility. An elderly described her situation thus: “No one is there to talk to me. I keep lying down all day. At night, I dream devils and keep awake. I pray to God to take me.”

Many elderly showed signs of anxiety, depression, and loneliness. One patient visibly depressed due to illness asked, “I don’t pray, what is the use? I would have hanged myself if I could; I even tried once, but fell flat on the bed.” He wept intermittently, trying hard to stop tears and was in deep agony. Another patient seemed to be awaiting death and said, “Father will take me; I am not taking any medicines.” His memory had grown weak, all prayers were forgotten and he only dreamt of Satan and people who had already died. Many were waiting in desperation for their final exit. One patient who was reluctant to take medicines and food, asked: “What is the need of all these medicines, why are you struggling for me, I will go (die) in this way.” Three male widowers expressed extreme loneliness after spousal death, especially because it increased the care deficit in old age.

A major problem was the lack of empathy from family carers. This is illustrated in the case of women who said “My daughter doesn’t talk to me. She says I am pretending that I cannot walk. Nobody is there to take care of me, everybody is angry at me.” Feelings of being a burden on family, anxiety over about unfinished tasks and responsibilities and poor finances weighed many down. A patient was worried about not having sufficient resources to get her younger daughter married. About 10 patients were overtly worried about financial difficulties. Eight patients (13.3%) were anxious about their future, as their children did not take care of them.

Out of sixty participants, 32 (53.3%) reported that they were satisfied with the support and care from their family. Ten participants (16.7%) reported that they were happy with the present living conditions. However, 18.3% (11) said that children did not take care of them and behaved rudely. Only 18 (30.0%) elderly reported that family members spent enough time with them. Three (5.0%) patients wept inconsolably throughout the interview and one even lamented not having any one to care for her. One elderly couple was in deep agony after their grandson's accidental death 2 months ago. The deceased was the lone caregiver for both of them while their own children stayed elsewhere. The husband was paralyzed and his wife was too weak even for self-care. Both sustained on food from neighbors and were obviously worried about their future.

However, caregivers’ profile showed that out of 49 family carers, 42 were females and 23 were above 55 years of age. They reported difficulty in caring for their patients as they themselves were suffering from different illnesses. Most of the female carers were suffering from osteoarthritis, manifested mainly as back pain or joint pain in legs. Family carers found caring tasks for bedridden patients very difficult on a regular basis. For women, primary care givers were mainly daughters (40.0%) followed by spouses (25.7%), whereas for men, primary care givers were their wives (68.0%). About 25.0% families said that they did not have any kind of support from society. In an environment characterized by dependence and deprivation, spirituality figured importantly in end of life. Nearly 98% of the participants believed in a supreme power and prayed from their homes because of their restricted mobility. More than 50% found praying as their only hope and solution. Another patient who was a devout believer said tearfully, “I cannot speak as before, voice trembles and I am not able to read the Bible during prayers.” Yet another patient said, “I pray during evenings; I pray to God to save all his children and me too. I often dream of a person/a vehicle coming to take me away.”

Access to palliative services and level of satisfaction of the respondents

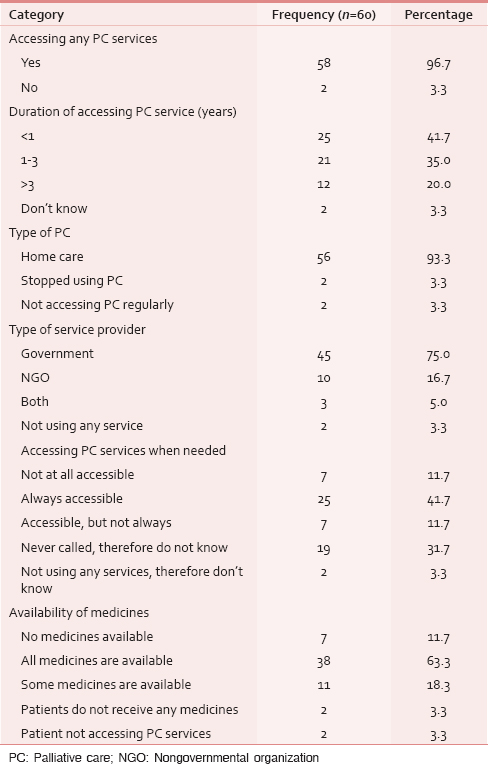

Out of sixty respondents, two were not using any palliative services. One of them was on Ayurvedic treatment after allopathic treatment from both government and private sector failed to yield any positive outcomes. The other had also accessed services from an NGO but had subsequently discontinued it due to the lack of improvement. Table 5 depicts the accessibility of PC.

It is apparent from the study sample that the government is the major provider of palliative services in the community. Three participants used both government and private services and among them one availed services from the Regional Cancer Centre (RCC), also. She was under the treatment of cancer esophagus and accessed services from government health center, NGO, and RCC Home care team. The family preferred the latter in terms of quality of services. Moreover, it found the RCC team accessible all the time, either directly or over phone. Only 41.7% found the services always accessible. Asked about the availability of medicines, 18.3% reported that some (and not all) medicines were available and attributed this to poor stock of medicines in the health center or due to high prices, which prohibited drug supplies to the health facilities. Fourteen persons confirmed that they had to purchase medicines form private pharmacies, the average cost of which came to Rs. 1142.9 ± 1190.8. Eight out of sixty reported delay in accessing PC services due to the unavailability of doctor/nurses [Table 6].

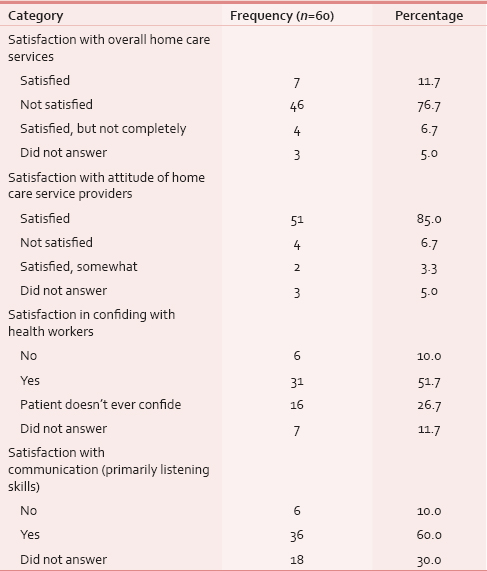

Field observations showed that 76.7% of the respondents were not satisfied with the services and all of them were using public services. Satisfaction with service components such asattitude of care providers, communication, and opportunity to confide was good, but irregular visits by PC nurses and nonavailability of doctors were the major causes of dissatisfaction. While a large majority (85%) found the attitudes of the service providers satisfactory, only 60% found their communication skills satisfactory. A little over half of the study participants could share their problems with PC providers and 26.7% were reluctant to confide with them. Six patients said they did not feel like confiding their problems with health workers.

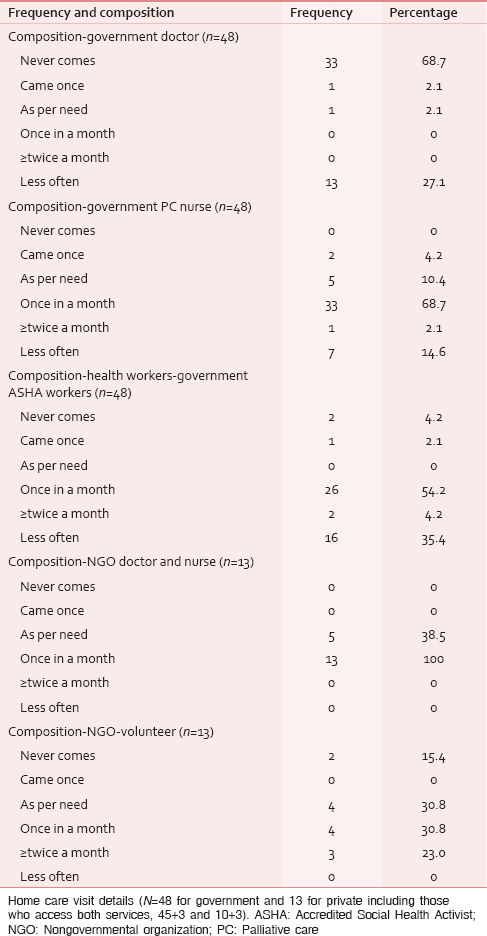

Probing into their opinion on frequency and composition of the palliative team, it appears that doctor led teams are rare (68.7%, said so). An equal number of respondents stated that the PC nurse visited them once in a month only and 54.2% reported poor visitations of Accredited Social Health Activist workers. Frequency of home visit was a major component in satisfaction and the responses varied according to composition of the visiting palliative team. Volunteer support also appeared weak with little consensus on frequency of visits.

The respondents were also asked to report the frequency of visits of frequency and composition of the palliative team. This is depicted in Table 7.

DISCUSSION

The study finds considerable care deficit and suggests the need to revisit the question: Is home-based PC, in its present form, the most efficacious model for the elderly in resource poor settings? Although family-home is widely acclaimed for its ability to serve as an alternative to institutional care for elderly since the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (UNFPA and HelpAge International, 2011), little evidence is available about specific contexts and structures which determine outcomes. It is in this respect that the present paper assumes importance.[15] The study shows that the panchayats covered under the study have people who are under extreme financial distress, many below the poverty line and without basic amenities such as shelter, and this prompts the question: What does home-care mean when there is no “home” to live in? One such homeless patient questioned, “Don’t we need a house for dying peacefully?” Her three sisters had recently died leaving her badly affected. Another patient, who lived with her sister in a shed, said “We don’t have a house, no means to live, then how can we be happy?” Under such conditions of deprivation, the present palliative service falls short of its intended goal to improve the quality of living and dying. It may be mentioned here that in those countries of the west where home care is encouraged, considerable government support has been extended to reconfigure homes through structural modifications to make them suitable for ageing and dying. These include locating homes within a continuum of care through technological measures and reconfiguring health delivery system in a way to ensure seamless care through palliative networks involving specialist palliative-home care teams and nurse-led teams.[6] In addition to this, Social Care Institute for Excellence (2013) reported that caring for elderly at home can be complex and messy, and therefore ancillary support structures like nursing homes, assisted living facilities and other long-term care settings facilitate ageing and dying in the community when home care becomes difficult.[16] Moreover, government policies support end-of-life care through several social security programs for both patients and caregivers. Short of such provisions, home dying may be complex and painful, especially for such communities, which are characterized by poverty, lack of necessary resources and skills, poor care at home, and inadequate health services.[17]

The study suggests that home-based palliation in its present form – clinical in approach and provided at irregular intervals – may not promote good end-of-life care for the present community. Overall, it appears that the palliative program as perceived by the respondents is characterized by poor doctor visitations and poor frequency of visiting teams. A marked feature of the responses is the lack of consensus on the palliative program. Perhaps, the heterogeneity of responses is indicative of the lack of a strong appreciation of such service in their lives.

Homes in the study do not carry the same connotations as in western countries. The popular imagery of well-served family homes in the west is not universal, and raises critical questions regarding end-of-life care in suboptimal conditions. A Longitudinal Ageing Study in India by Arokiasamy et al. found a large number of elderly population live in households that lack running water, proper sewer system and poor indoor air quality due to cooking fuels. All these factors negatively affect the health of older persons.[4] Such findings warrant the question: What is the likely impact of poor housing on quality of life and death of home bound elderly?

The study shows that for some respondents, the agony of poor, as well as homeless existence was compounded by serious multiple morbidities, particularly locomotor and speech problems [Table 3]. Field observations show that the latter rarely command attention from palliative team. In fact, the field investigator had difficulty in deciphering their voices, which were already silenced, metaphorically speaking. The preponderance of chronic diseases and disabilities draw our attention to existing palliative program in the state and elsewhere in India, which are overtly disease-specific involving cancer or stroke, and less adapted to the needs of the geriatric populations.

Finally, the high dependency of the aged, both physical and financial, also begs a query: What are the subjective meanings of ageing and dying for those who are living under such deplorable conditions? Does home retain the same meanings for them as for the young and the well off? Does the positive meaning of home sustain for such older people, many of whom also report abuse and neglect? It may be mentioned here that identifying the single, sick, and the vulnerable has been considered as an important area of concern in the National Policy on Older Persons (NPOP-1999).[18] Paradoxically, despite reference to the plight of the single and the destitute, NPOP continues to lay emphasis on noninstitutional services only, considering institutionalization as the “last resort.”

The unmet needs for palliation and care deficit at home have evoked poor satisfaction levels among the respondents – around 77% of the patients were not satisfied; almost all complained of poor frequency of palliative visits, which implied poor support for ageing and dying at home. A matter of great concern for the study was the widowed elderly and those who had no independent earning or family caregivers. This study reports that dependent, widowed elderly women were more vulnerable to abuse and maltreatment in the family – a fact corroborated in a study by Sebastian and Sekher in 2011.[19] At present, social security schemes by the state are too meagre and irregular to be of much consequence to their lives, and push them into perpetual anguish about future. This picture represents the general lack of social support system for elderly across the country.[2] It is in the context of such deplorable condition, that the mere medical model of PC appears rather limited in scope and fragmented in its goal. The present palliation clearly lacks an integrated approach as envisaged in the Draft Palliative Care Policy (2008) drawn for the state.[20]

Strengths and limitations of the study

There are few studies on end-of-life characteristics of the elderly population served by home based palliative program in Kerala. The present study, thus, provides insights in an area which has little evidence base. The major strength consists in questioning the rhetoric of home based palliative program for poor communities, and highlighting the unmet need for end-of-life care. It raises many critical issues about home care which are being presently overlooked by service providers.

The major limitation of the study stems from its lack of generalizability due to its small scale of investigation involving only sixty respondents in two panchayats of Kerala.

CONCLUSION

The study has found poor quality of ageing and dying in the two gram panchayats of Kerala serviced by home-based PC. The study finds that home-based palliation in its present form does not promote good end-of-life care. The paper raises serious questions on family-home as the locus of ageing and dying for marginal populations, and suggests need for restructuring of the palliative program.

Financial support and sponsorship

Ministry of Human Resource Development, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The study is part of the Ministry of Human Resource Development funded project: Improving End-of-Life Care for the Elderly through Indic Perspectives on Ageing and Dying, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur.

REFERENCES

- HelpAge India. 2015. India Spends Mere 0.032% of GDP on Senior Citizens: Study; 20 February 20, 2015. New Delhi: The Economic Times; Available from: http://www.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/india-spends-mere-0-032-per-cent-of-gdp-on-senior-citizens-study/articleshow/46316259.cms/

- [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation. In: Situation of the Elderly in India. New Delhi: Central Statistics Office, Government of India; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. Population Composition. Census Report 2011. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital./9Chap%202%20.%202011.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Longitudinal aging study in India: Vision, design, implementation, and preliminary findings. 2012. Aging in Asia: Findings from New and Emerging Data Initiatives. Washington, DC: National Research Council (US) Panel on Policy Research and Data Needs to Meet the Challenge of Aging in Asia: National Academies Press (US); Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK109220/

- [Google Scholar]

- A cross sectional study of the morbidity pattern among the elderly people South India. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2013;2:372-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. 2011. Census Report. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/prov_data_products_kerala_html

- [Google Scholar]

- Elderly Population: State Scores a First. 2014. Centre for Development Studies. The New Indian Express. Available from: http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/thiruvananthapuram/Elderly-Population-State-Scores-a-First/2014/09/20/article2440451.ece

- [Google Scholar]

- Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index for India's States. UNDP India 2011:15-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regional Cancer Centre. Incidence of Cancer in Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram. Available from: http://www.rcctvm.org/lifestyle%20and%20cancer.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Age-specific analysis of reported morbidity in Kerala, India. World Health Popul. 2007;9:98-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population aging and health expenditure in Kerala: An empirical analysis. In: Hoque N, McGehee MA, Bradshaw BS, eds. Applied Demography and Public Health, Applied Demography Series 3. Netherlands: Springer; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- The evolution of palliative care programmes in North Kerala. Indian J Palliat Care. 2005;11:15-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Public health approaches in palliative care. In: Sallnow L, Kellehear A, Kumar S, eds. International Perspectives on Public Health and Palliative Care. Routledge Studies in Public Health. London: Paperback-Import; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA and HelpAge International. Overview of Available Policies and Legislation, Data and Research, and Institutional Arrangements Relating to Older Persons – Progress Since Madrid. New York: UNFPA; 2011.

- 2013. What Older People Want: Commissioning Home Care for Older People. Available from: http://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/

- Gott M, Ingleton C, eds. Living with Ageing and Dying: Palliative and End of Life Care for Older People. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Extent and nature of elder abuse in Indian families: A study in Kerala. Help Age India Res Dev J. 2011;17:20-8.

- [Google Scholar]