Translate this page into:

Evaluation of Community-based Palliative Care Services: Perspectives from Various Stakeholders

Address for correspondence: Dr. Vinayagamoorthy Venugopal, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital, Puducherry - 605 107, India. E-mail: drvinayagamoorthy@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

As a part of Memorandum of Understanding with Tamil Nadu Institute of Palliative Medicine, community-based palliative care services have been initiated 2 years back in our urban field practice areas.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the home care service, a major component of our community-based palliative care, with a view to identify the unmet needs of the services rendered for decision-making about the program.

Materials and Methods:

It was a descriptive qualitative design carried out by the authors trained in qualitative research methods. In-depth interviews were done among four patients, seven caregivers, two social workers, six nursing staffs, and six medical interns for a minimum of 20 min. Interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim, and content analysis was done manually. Ethical principles were adhered throughout the study.

Results:

Descriptive coding of the text information was done; later, similar codes were merged together to form the categories. Five categories under the theme of strengths and five codes under the theme of challenges of the home care services emerged out. Categories under strengths were physical management, psychological care, social support, efficient teamwork, and acceptance by the community. Codes for felt challenges were interdisciplinary collaboration, volunteer involvement, training enhancement, widening the services, and enhancing the community support.

Conclusions:

This review revealed the concerns of various stakeholders. There is a need for more interprofessional collaborations, where team members understand each other's roles for effective teamwork, as evident from the framework analysis.

Keywords

Community-based palliative care

framework analysis

home care

qualitative evaluation

INTRODUCTION

Community-based palliative care (CBPC) services are those offered at a community health center or that are run with community participation.[1] It is a nonhospital, nonhospice palliative care provided in patient homes, in clinic or over the phone.[2] It is generally patient-centered, comprehensive, and cost-effective. CBPC involves service delivery by both multidisciplinary teams of health-care professionals and community health workers/volunteers.[3] Home care service is the crux of the CBPC service. The ultimate goal of home-based care is to “promote, restore, and maintain a person's maximum level of comfort, function, and health, including care toward a dignified death.[4]

As a part of Memorandum of Understanding signed with Tamil Nadu Institute of Palliative Medicine, in the year 2015, CBPC services were established at four villages situated in the study setting, mentioned below. It was a new program initiated with limited preexisting resources, basic training, and planning. Hence, it was decided to carry out an internal evaluation, to illuminate on the unmet needs for further decision-making. The evaluation is primarily based on the detailed and comprehensive understanding of the perceptions of various stakeholders about the services and incorporates in improvement of quality and services. Such exercise is crucial to align the program to expectations of people in the given context and also improve the sense of belonging among the field staff by considering their suggestions, which is the key to long-term sustainability of the program.

Neighbourhood Network in Palliative Care (NNPC)[5] model in Kerala served as a platform to transform the doctor-driven palliative care to community-owned, volunteer-driven initiative. This model was instrumental to devise palliative care policy under National Rural Health Mission. The CBPC program has the potential to empower the community and utilize the social capital to serve the people in need of palliative care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

It was a descriptive qualitative design carried out with the help of one to one in-depth interviews.

Study setting

CBPC services were established at four urban slums at Villupuram district of Tamil Nadu. They constitute the field practice areas of the urban health training center (UHTC) of a tertiary care teaching hospital. These urban slums are situated 30–40 km from the medical college which is located within the rural pocket of Puducherry, Union Territory. UHTC provides promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care services to a population of around 22,000. Palliative care is provided through the faculties, medical social workers, field staffs, and medical interns. Faculties were trained in palliative care at Institute of Palliative Medicine, Calicut, Kerala.

Study participants

Study participants were various stakeholders of the program, namely, palliative care patients, caregivers, medical social workers, auxiliary nurse midwife, diploma nursing assistant trainees, and medical interns. A sample of varied stakeholders was adopted as the study was exploratory and sought to gain a wide range of viewpoints from all service providers and beneficiaries in relation to their perceptions and experiences of the CBPC service. Beneficiaries who were vocal and willing, service providers who have more years of experience were purposively sampled to obtain maximum variation in information.

Data collection

The in-depth interview was facilitated using a semi-structured interview guide to capture the deeper meaning of experiences of the participants regarding CBPC services provided and received in their own words. Semi-structured in-depth interview is a flexible approach that encourages building a rapport between the facilitator and participants which results in the yield of more reliable and trustworthy response from the study participants. Interviews were conducted in Tamil, the local language, from various stakeholders. Participants were interviewed between November and December 2016. First and second authors trained in qualitative methods carried out one to one interview with various stakeholders. Each interview lasted about 20–40 min in a place convenient and comfortable to the participants.

Data analysis and interpretation

Interviews were audiorecorded and then they were translated to English and transcribed verbatim by the first and second authors who were trained well enough in carrying out qualitative data analysis. Manual content analysis was carried out using the framework approach. The complexity of qualitative data is captured effectively using this approach. This enables the grouping of similar responses across study participants and assists the researchers to categorize the findings and attach them to the areas being explored. The guidelines by UCLA Center for Health Policy Research were used for analysis.[6]

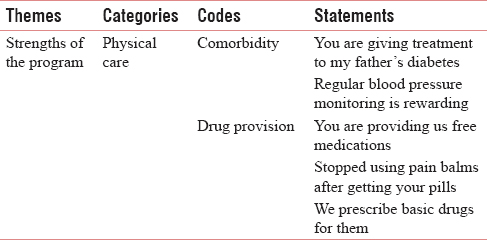

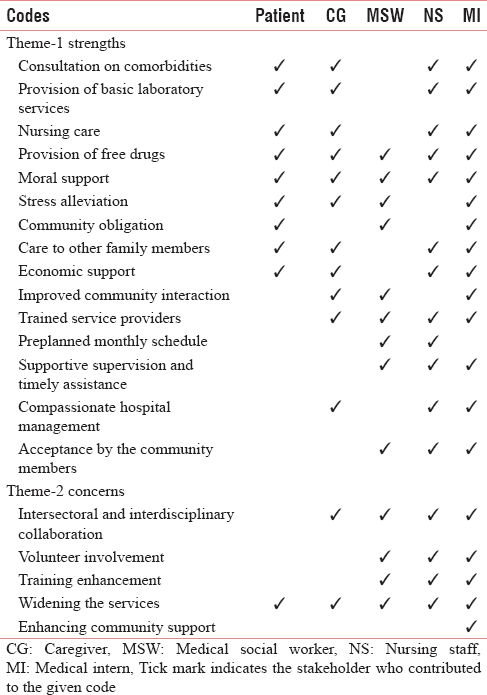

The process began with the primary analysts (first and second authors) reading each transcript multiple times. These analysts then independently coded significant text information in the transcripts and interpreted the meaning of each statement, organizing the derived meanings into formulated concepts about review of CBPC services. Next, the codes related to similar areas were clustered together to form the categories. Finally, similar categories were grouped to form themes to explore the provided services comprehensively [Table 1]. The third author reviewed the themes. Discrepancies in the emerging codes, categories, and themes between the analysts were compared and reconciled. Primary analysts finally discussed the concepts and themes with the third author to refine and reach consensus. Result of framework analysis was depicted in Table 2.

Statements in italics indicate direct quotations or verbatim from the respondents and the quotations stated, are either in support or an addition to the description of results, help to explain what respondents shared. The “Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research” guidelines have been followed while reporting this qualitative work.[7]

Ethical issues: Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and ethical principles were adhered throughout the study.

RESULTS

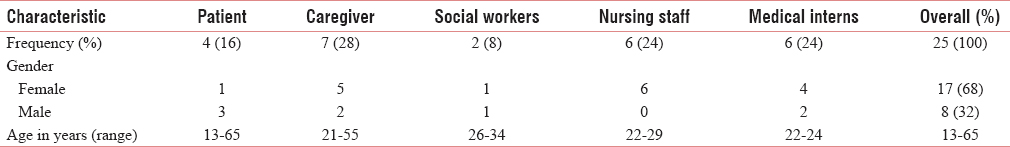

Various stakeholders who were interviewed about the CBPC services were patients (4), caregivers (7), medical social workers (2), nursing team members (6), and medical interns (6). The largest stakeholder group interviewed was caregivers, comprising 28% of the participants. Overall more female participants were interviewed (68%). The participant's age ranged from 13 to 65 years [Table 3].

Theme 1: Strengths of the community-based palliative care service

The in-depth interviews with various stakeholders resulted in 91 significant statements. They were grouped into 15 formulated codes that explained various strengths of the program from the participant's deeper understanding and perception. These codes were then clustered under 5 categories, namely, (1) physical management, (2) psychological care, (3) social support, (4) team coordination, and (5) acceptance by the community [Table 2].

Category 1: Physical management

All stakeholders perceived that managing physical symptoms of chronic incurable illness, treating associated comorbidities and seasonal ailments, doing wound dressing and other nursing procedures, and provision of free drug and basic laboratory services at patients doorstep as main strengths of the program.

Code 1.1: Consultation on associated comorbidities and seasonal ailments

A 31-year-old female, a caregiver, said, “We are happy that you are treating my father's end-stage disease along with his sugar disease and you are checking his blood sugar at home during your visit.”

Code 1.2: Provision of basic laboratory services

People were able to appreciate that we provide basic laboratory services at their doorstep which included blood sugar monitoring, collection of blood, urine to estimate various biochemical parameters, and sputum samples to rule out pulmonary tuberculosis.

Code 1.3: Nursing care

Patients who received nursing care were satisfied about the service, and many caregivers expressed that they learned to give nursing care to their loved ones on daily basis without depending on others and without spending money. Medical interns informed that this was a great learning experience for them to do bedsore dressing, wound care, and urinary catheterization to the needy patients at the community setting.

A 32-year-old female, caregiver, told “Now I learned how to do dressing for my husband and so I am doing it daily.” Medical intern told, “I learned many nursing cares during this posting, especially bedsore dressing and urinary catheterization.”

Code 1.4: Provision of free drugs

Drugs were provided free of cost not only to treat underlying pathology but also to treat some chronic noncommunicable diseases and seasonal illness that greatly reduced the economic burden on the family.

Category 2: Psychological care

There exist many factors that give rise to dissatisfaction, disgust, anxiety, depression, and mood swing among people who require palliative care, and hence, psychological care is an essential part of palliative care. The moral support provided to the patients and their caregivers were well received and appreciated by all stakeholders. Everybody felt stress alleviation to the patients and caregivers was the most rewarding strength of the program.

Code 2.1: Moral support

Medical interns and social workers felt that mere medications and hospital care were not sufficient to relieve the sufferings of patients.

A 62-year-old male patient who was a stroke victim with hemiplegia when asked about the best part of the program he said, “Nobody talks to me and they neglect me but you were coming from long distance and talking well to me, I feel someone is there to support and take care of me.”

Code 2.2: Stress alleviation

One of the patients expressed that the team was a source of stress buster for him. Some of the caregivers said that the reason for their mental relaxation was the CBPC service providers. Social workers and medical interns who visited them pointed out that patients and caregivers were waiting to share their emotional sufferings with them.

Category 3: Social support

Invariably, all stakeholders perceived the social support offered by the team as one of the strengths of the program. Stakeholders perceived that the program not only cared the patients but also supported other family members. Reducing out of pocket health expenditure, improving social interactions, and bringing out compassionate community members were appreciated strengths of the program.

Code 3.1: Community obligation

Caregivers mentioned us that the neighbors and other community members were not visiting them or talking to them properly, but our regular visit made them to realize the importance of compassion toward patients. Medical interns expressed that they learned patience and empathy by serving them.

A 45-year-old mother, caregiver of a mentally retarded child, said, “Before you visit my child, the other children and neighbors used to tease my daughter. Your visit raised their awareness and improved their responsibility. Now they stopped teasing her.”

Code 3.2: Care to other family members

Patients and their caretakers explained with gratitude that the team during the home care visit checks and caters to the needs of the family members apart from providing care to the patients. They were delighted, which is a unique feature of the program.

Code 3.3: Economic support

As our home care services are provided free of cost and at their doorsteps, they were impressed and mentioned that the drugs, nursing services, and laboratory checkups that were served free of cost helped them to reduce out of pocket health expenditure. Over the counter drugs, usage has reduced, thereby reducing economic burden of the family.

Code 3.4: Improved community interactions

When asked what changes happened after initiation of the program, patients and caregivers told that they started participating in the social events of relatives and friends. They said that before the CBPC program, there was no much interaction between family members and community.

Category 4: Efficient teamwork

Service providers along with the patients and their family members wholeheartedly accepted that the program was running successfully mainly because of the efficient and motivated team members. Trained workforce, timely assistance, supportive supervision, preplanned program schedule, and compassionate management were all helping them to render the service effectively.

Code 4.1: Trained service providers

Medical social workers told that the orientation to palliative care offered to them before initiating the program and the training given then and there after implementation of the program made them work confidently and stress free. Medical interns expressed 1-day orientation program given on the day of joining the department helped them to provide care effective care and support to the patients and family members.

Code 4.2: Preplanned monthly schedule

All the service providers said that the program schedule prepared on monthly basis to visit identified patients in all urban slums was really helping them to plan other activities along with palliative care services. Patients and caregivers told that they very rarely missed weekly home care service provided.

Code 4.3: Supportive supervision and timely assistance

Nursing staff and social workers mentioned that the supervisors, who accompany them during home care visit, were supportive, encouraging, and motivating. They added that their higher official's intention was not finding faults and scolding them but to correct their mistakes and to improve the quality of the care provided to the patients. Social workers said, “Monthly once training conducted in the UHTC by our supervisors helped us to clarify our doubts then and there.”

Code 4.4: Compassionate hospital management

Patients and caregivers were of the impression that even government was not providing such free service at doorstep but the home care team that was a part of private institution was able to serve. Social workers and nursing staff admitted that all these free services were provided to the needy because of the support given by the hospital management which was the main strength of the program.

Category 5: Acceptance by the community members

Patients, caregivers, and the community members appreciated and received the program well. Staff nurses mentioned that on arrival, they invited them gladly. Medical social workers said that the community members greeted them with respect and spoke politely, and this attitude of the community members was motivating them to serve better. Medical interns told that all patients though were terminally ill, their caregivers were extremely cooperative. It was evident from the words of the stakeholders that this CBPC program was accepted by the people.

When asked about the strengths of the program, medical social worker said, “Even on their terminal stage of illness, on seeing us, they smile at us, it gives us immense pleasure and motivation.”

Theme 2: Inferred concerns for further improvement of the program

When interviewed about the perceptions of stakeholders to improve the performance of the program in a better way, everybody gave their genuine comments and suggestions. These were coded and categorized. Twenty-eight codes emerged under the challenges of the program were clustered into five broad categories [Table 2]. They were outlined below.

Code 1: Intersectoral and interdisciplinary collaboration

A 25-year-old male, caregiver, informed, “If possible, please arrange physiotherapist visit to train my father.” “Please tell panchayat leader to arrange proper housing through any government scheme,” a caregiver of elderly patient requested.

Code 2: Volunteer involvement

Social workers and medical interns who were exposed to the concept of volunteerism in palliative care rightly expressed that identifying and training volunteers will help patients to receive care on a daily basis without interruption of any emergency service to them.

Code 3: Training enhancement

Social workers, nursing staff, and medical interns told that the major concerns of the patients and caregivers were emotional in nature, so we need more training on communication skills and on handling difficult situations in field.

Code 4: Widening the services

Caregivers suggested us to give free drugs to the other noncommunicable diseases of the patients and other family members. Medical interns suggested doing more laboratory services free of cost at doorstep to them. Social workers suggested arranging for vehicle in need of emergency to the patients.

Code 5: Enhancing community support

Social workers suggested that team members should participate in the condolence meeting and rituals when the patients expire. They suggested that this will enhance the social support and community participation of the program. Medical interns suggested that raising fund for the program through nongovernmental organizations, self-help groups, youth clubs, and other welfare societies will help to serve more people in need.

Medical social workers contributed to the codes related to their community-oriented aspects. Patients and caregivers contributed to the codes representing the services they received. Medical interns contributed almost to all codes as seen from the result of framework analysis [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

Overall the community-based palliative care program was well received by the patients and caregivers. The service providers reported that the patients perceived the care to be good and satisfying. The evaluation of the program done among various stakeholders revealed the strengths of the program as physical, psychosocial care provided the effective teamwork and acceptance of the program. The areas of improvement which came up were intersectoral collaboration, volunteer involvement, training enhancement on communication skills, and widening the services provided. These findings, however, are context specific. Hence to make the program acceptable in the community, planning, implementation, and evaluation of services should be tailored to the needs of the local people.

We followed the WHO guidelines and NNPC model for implementation of our CBPC model. Studies done across the world,[89101112] which used various guidelines,[12311] showed that an effective CBPC model comprises seamless coordination, holistic care, communication and relationship development, and empathy and understanding of the patients and carers. The evaluation of such CBPC services revealed good acceptability among various stakeholders. A systematic review[13] of the self-reported unmet needs of patients and carers treated at home-based palliative care program in the UK showed that the physical needs of the patients were treated satisfactorily but lacks effective communication skills. Communication skill forms an important attribute of palliative care providers and so forms a major domain of CBPC services.[101415] This is primarily to deal with the nonphysical psychosocial needs such as honoring patient's wishes, delivering compassionate care, preparing for death, and understanding family needs and relationship development. Although the program addressed most of these issues, social workers and medical interns felt that they need intense advanced training in communication skills. It is always challenging to deal with the emotional needs of the palliative care patients, and it warrants effective training in this area.

Framework analysis revealed that medical interns fairly contributed to all codes. The possible reason could be they were exposed to orientation program on palliative care at the beginning of their posting in the department. It is evident that there is a need for more interprofessional collaborations, where team members understand each other's roles for effective teamwork. Evidence shows that the unmet needs of various complex health issues can be managed by the collaborative practice-ready health workforce through interprofessional education and collaborative practice.[16]

Stakeholders perceived that CBPC program reduced the direct and indirect cost of health expenditure. Previous studies on impact of home-based palliative care program also showed reduction of health-care cost of the patients and reduced hospitalization in the past 3 months of the patient's life.[171819]

Limitations

Although the study interviewed range of stakeholders, selection of them was purposive, and this might have resulted in the exclusion of the opinions of those not being selected. Nonavailability of some of the patients and carers at the time of visit is another factor that restricted to understand the experiences of all stakeholders. Review by the internal member of the program could be considered as a limitation, but the reviewers know the purpose, and this was the part of ongoing program evaluation to understand the strengths and challenges of the program.

CONCLUSIONS

On the whole, the respondents perceived that the services provided by the CBPC program were worth appreciating and admirable. The service provider's level of satisfaction was also high. All the interviewed stakeholders stated that the program resulted in better physical and emotional care of the chronically ill patients, thereby improving the symptom relief and reducing the health expenditure. It has also taken care of the caregivers, other family members, and community. Therefore, it appears that most of the needs of the people are met through the CBPC program. However, there have been certain areas as highlighted by the participants which need improvement. They were communication skills enhancement of social workers and nursing staff as they ought to address the emotional issues of the patients and carers most of the time. Next one was fund generation by the local people to keep themselves equipped to manage unexpected needs and to sustain the program by them and finally widening the services so that majority of their chronic symptoms will be taken care.

Recommendations

Identification, motivation, and training of volunteers who are available within the vicinity of the patients are mandate. Training of caregivers to assist the patients to do simple nursing cares and physiotherapy exercises at their residence needs to be planned. Involving local leaders to generate funds in innovative ways will improve the overall penetrance of the program. All these activities will improve the self-sustainability of the program and empower the community to identify and arrive at feasible solutions for the problems. Attending the condolence meetings/death rituals/funeral by any field staffs of the team will help to obtain the faith of family members and community which will improve the overall scope of the program.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We sincerely acknowledge the management, faculties, and other team members of our college (SMVMCH) for supporting and encouraging us to provide palliative care services to the needy.

REFERENCES

- Planning and implementing palliative care services: a guide for programme managers. Available from: https://www.google.co.in/?gfe_rd=cr&ei=4xjdWIWrPIqP2ATt1qigBA#q=planning+and+implementing+palliative+care+ services+a+ guide+for+programme+managers&*

- A Field Guide to Community-Based Palliative Care in California. California Healthcare Foundation. Available from: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/PDF%20U/PDF%20UpCloseFieldGuidePalliative.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. Available from: https://www.google.co.in/search?q=Global+Atlas+of+Palliative+Care+at+the+End+of+Life&oq=Global+Atlas+of+Palliative+Care+at+the+End+of+Life&aqs=chrome.69i57j0l2.4463j0j8&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

- Kerala, India: A regional community-based palliative care model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:623-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- UCLA Center For Health Policy Research: Section 4: Key Informant Interviews. Available from: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/ programs/health-data/trainings/Documents/tw_cba23.pdf

- Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABC of palliative care. Principles of palliative care and pain control. BMJ. 1997;315:801-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Comparative Study to Assess the Awareness of Palliative Care Between Urban and Rural Areas of Ernakulum District, Kerala, India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:122-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care: Benefits, services, and models of care. Available from: http://ultra-medica.net/Uptodate21.6/contents/mobipreview.htm?29/6/29801?source=see_link

- Public awareness and attitudes toward palliative care in Northern Ireland. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Home-based palliative care: A systematic literature review of the self-reported unmet needs of patients and carers. Palliat Med. 2014;28:391-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Communication skills in palliative care: A practical guide. Neurol Clin. 2001;19:989-1004.

- [Google Scholar]

- Communication with relatives and collusion in palliative care: A cross-cultural perspective. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:2-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2010. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva: WHO; Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/

- Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:1-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: A literature review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:130-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Impact of Community-Based Palliative Care on Utilization and Cost of Acute Care Hospital Services in the Last Year of Life. J Palliat Med 2017 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0417. PubMed PMID: 28437201. [Epub ahead of print]

- [Google Scholar]