Translate this page into:

Fatigue and Quality of Life Outcomes of Palliative Care Consultation: A Prospective, Observational Study in a Tertiary Cancer Center

Address for correspondence: Dr. Mary Ann Muckaden; E-mail: muckadenma@tmc.gov.in

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Purpose:

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms seen in patients with advanced cancer. It is known to influence the Quality of Life (QoL) of patients. This study examines the interrelationship of fatigue and QoL in patients with advanced cancer on palliative care.

Methods:

A prospective cohort study was conducted in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Palliative Medicine from January to June 2014. Patients with advanced cancer registered with hospital palliative care unit, meeting the inclusion criteria (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] ≤3, Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale [ESAS] fatigue score ≥1), and willing to participate in the study were assessed for symptom burden (ESAS) and QoL (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Core 15-Palliative module [EORTC-QoL PAL15]). All study patients received standard palliative care consultation and management. They were followed up in person or telephonically within 15–30 days from the first consult for assessment of outcomes.

Results:

Of a total of 500 cases assessed at baseline, 402 were available for follow-up (median age of 52 years; 51.6% male). On the EORTC-QoL PAL15 scale, overall QoL, emotional functioning, and constipation were found to be significantly associated with severity of fatigue at baseline (P < 0.05). Statistically significant improvement in fatigue score was observed (P < 0.001) at follow-up. Improvement in physical functioning and insomnia were significantly associated with better fatigue outcomes.

Conclusions:

Fatigue improved with the standard palliative care delivered at our specialty palliative care clinic. Certain clinical, biochemical factors and QoL aspects were associated with fatigue severity at baseline, improvement of which lead to lesser fatigue at follow-up.

Keywords

Fatigue

Indian tertiary cancer center

Palliative care

Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Quality of life (QoL) is a significant concern for patients with advanced cancer. Poor QoL has a cause and effect relationship with fatigue, insomnia, and psychological distress.[12345] Cella has defined health-related quality of life (HRQL) as “The extent to which one's usual or expected physical, emotional, and social well-being are affected by a medical condition or its treatment.”[6] This definition incorporates two widely accepted aspects of QoL: subjectivity and multidimensionality.[7] HRQL is a construct which represents individual's subjectivity more than objectivity. The subjective appraisal of HRQL makes patients with the same objective health status report differently due to unique differences in expectations and coping abilities.[8]

Several studies on Caucasian population have demonstrated the adverse impact of fatigue on physical, emotional, economic, and social aspects in the lives of cancer patients.[291011121314] In a study conducted in a group of cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy, fatigue as measured by the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) was associated with poor QoL. It was considerably lower before treatment started than at posttreatment or follow-up, suggesting that fatigue can be encountered even when treatment has ended.[12] Tanaka et al. conducted a study on sixty patients with uterine cancer treated at a university hospital in Sweden. In this study fatigue was measured on MFI-20 and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30) fatigue subscale. Results showed that fatigue was significantly associated with global QoL.[2] In another study, conducted on 171 patients with advanced lung cancer, fatigue was found to interfere with at least one daily life activity in more than half of the patients.[13]

Interestingly, some studies reported that fatigue decreases at the end of life. This was explained to be a kind of adaptation to the situation as was shown in a study done by Sprangers and Schwartz in 1999.[15] This phenomenon has been backed by the proposals from the EAPC working group on fatigue in palliative care – fatigue in the final stage of life may serve as a protection mechanism which relieves suffering. Furthermore, Wu and McSweeney 16 have supported the same opinion and have associated fatigue with a positive meaning in life. According to them, it serves as a defense mechanism protecting the patient from psychological collapse. This is postulated to be because of the changes in patients’ perception of goals of care, values or priorities in life in their last days, which in turn brings about a change in the perception of fatigue.

In a systematic review of published literature, it was found that fatigue negatively affects patients’ QoL in advanced cancer.[17] A majority of the studies were retrospective, outpatient-based or cross-sectional in nature; in some patients were not routinely screened before enrollment but a convenience sample was used; whereas, some had parameters other than fatigue as their primary outcome measure.[1718] Fatigue — a subjective entity, varied in measurement across different studies due to the use of multiple symptom inventories, rather than a single standardized one. In some studies, there was lack of detailed information, i.e. history of cancer treatment, biological data of cancer, biochemical parameters, different stages and sites of metastatic lesions of cancer and a broader range of psychosocial data. The statistical models used to predict the factors associated with improvement of fatigue in certain instances failed to attain the required outcome measure (as indicated by adjusted R2). Several authors highlighted the need for larger RCTs or prospective studies.[1718]

It is well established that fatigue significantly impacts all domains of QoL, but it is often underdiagnosed and undertreated. Although there are studies on pain and QoL,[1920] there are none from Indian centers on cancer-related fatigue and its impact on QoL. Our study tries to address gaps in literature pertaining to Indian population.

Using a prospective design, this study attempts to unravel the complex relationship between two very intermingled constructs, QoL, and cancer-related fatigue. It was conceptualized with a primary objective of determining the effect of fatigue on QoL items in patients with advanced cancer. The secondary objective looked into QoL items associated with improvement in fatigue with standard palliative care consultation. We postulated that fatigue negatively affects the QoL in patients with advanced cancer.

METHODS

Study patients

This was a prospective observational study carried out over a period of 6 months from January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2014 at the Department of Palliative Medicine, Tata Memorial Centre (Mumbai). Posters were used to solicit the participation of prospective research subjects in the study. Due diligence was taken to ensure that the procedure for recruiting cases was not coercive or stated or implied a certainty of favorable outcomes or other benefits beyond what is outlined in the consent document and the protocol. All patients presenting to the outpatient clinic of the palliative care service were screened and accrued as per the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were all literate adult patients (age ≥ 18) with advanced cancer having an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score ranging from 0 to 3, a fatigue score > 0 on Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), and prognosis of > 4 weeks’ predicted survival who were willing to adhere to a follow-up schedule at the hospital or over the phone 15–30 days after the visit. The exclusion criteria were patients with ECOG score of 4, ESAS fatigue score of 0, predicted survival of ≤ 4 weeks, or unwilling to adhere to follow-up. All patients who participated in the study completed written informed consent form at the time of their initial enrollment. Compensation in any form was not provided for taking part in this study. However, necessary facilities, emergency treatment, and professional services were made available to the study subjects, as similar to the usual procedures of the hospital. Due diligence was taken to protect the patients’ confidentiality. The Institutional Review Board of the Hospital approved the study (Project No: 1181) and it was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI REF/2014/02/006537).

Study procedures

All study-related procedures including data collection were performed by the author and coauthors, all physicians trained in palliative medicine for 1–3 years. We did a baseline assessment of the participants at the first visit to the outpatient clinic. It involved medical consultation, recording of sociodemographic information and symptom scores using ESAS (to be completed by study subjects), performance score using ECOG, basic anthropometry (height and weight), blood investigations (hemoglobin and albumin), recording of daily morphine/oral morphine equivalent consumption, and QoL assessment using the EORTC QLQ-Core 15-Palliative module (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL). Follow-up assessment was done 2–4 weeks after baseline assessment either by personally or by telephone for a small proportion of patients who could not come. Procedure of follow-up assessment was similar to that at the baseline. All patients received standard palliative care intervention from our clinic. Because some patients may require more frequent visits with the palliative care team, either the patients or the palliative care clinician requested and scheduled more frequent visits at their discretion. If study patients were admitted to the hospital in the due course of the study, the palliative care team visited them on a daily basis throughout their admission. Patients received referrals to other care providers as and when needed.

Palliative care intervention: Standard procedure

A consultation includes a thorough palliative care-focused history, physical examination, and discussion of recommendations for further assessment or therapy with the physician. A comprehensive care plan is formulated. It addresses uncontrolled physical symptoms and correction of correctable parameters (anemia, electrolyte abnormalities, etc.). Fatigue is managed by a rational use of a combination of drugs (megestrol acetate, dexamethasone), dietary counseling, addition of diet supplements such as L-carnitine, protein supplements in consultation with dietician (if required), and exercise with light- to moderate-intensity walking programs initially for shorter periods of time that builds in intensity with time and patient education. The clinic also addresses psychological issues such as anxiety, adjustment disorders, depression, and anger. It facilitates in decision-making with thorough discussions about the understanding of the extent of illness, treatment options, and complications, addressing communication needs not addressed earlier. The medical social workers help in empowerment and enhancement of social support in the present family situation to address loss of income or identity. Counselors help in enhancing spiritual support and dwindling faith. Rehabilitation therapists help in solving practical issues such as mobility and impaired activities of daily living. After these initial procedures, patients are reassessed on follow-up appointments or through home-based care as per the necessity. Any palliative care medication or nutritional supplement needed by the patient is dispensed to them in the clinic, and the nurse explains the patients and their family what they are and how to use them.[21]

Study end-points

-

Determining the associations of sociodemographics and disease-related information during initial visit on QoL and fatigue

-

Determining the associations of QoL items with severity of fatigue at baseline

-

Identifying which QoL items are associated with an improvement in fatigue on follow-up after a standard palliative care consultation.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation: This study was an observational prospective study conducted at 5% significance level. No formal sample size and power estimation were done as no prior information regarding the factors affecting fatigue to calculate the sample size in our population was available. It was decided that all eligible consenting consecutive patients having a fatigue score in ESAS ≥ 1 would be enrolled for the study over a period of 6 months. Total number of subjects enrolled was 500.

Distributions of data were examined by analyzing the data graphically. If the data appeared to be nonnormally distributed, nonparametric equivalents of the parametric tests described in the results below were used for analyses:

-

Descriptive statistics – to summarize patients’ details such as, age, gender, geographic distribution, income, education, marital status, cancer type, stage, metastasis, comorbidities, type of treatment received, ECOG, hemoglobin, albumin, body weight, daily oral morphine consumption equivalent, ESAS symptom score of fatigue, albumin, hemoglobin, and QoL as measured in EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL were recorded at baseline and follow-up visit

-

Correlation coefficient – to determine if there was any association between fatigue and other parameters at baseline using Chi-square test/Spearman's rank order for association

-

Multiple linear regressions of data at baseline with fatigue in ESAS as the dependent variable was used to determine the predictive factors associated with the severity of fatigue

-

Mean/median ESAS fatigue score was recorded at baseline and follow-up

-

Comparison of ESAS fatigue scores and QoL scores as measured in EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL at baseline and follow-up by Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonparametric data to determine if there is any significant improvement in fatigue from baseline to follow-up

-

Logistic regression model was used to predict improvement in fatigue at follow-up

-

Analysis between patients on follow-up (n = 402) and who did not (n = 98) at baseline by comparing continuous variables using Mann-Whitney U-test for nonparametric data and categorical variables was determined using Chi-square test.

All analyses were carried out using SPSS 20 (IBM Corp., SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, USA). Missing data were noted and excluded from analyses and P values of 0.05 or less were deemed to be statistically significant.[22]

RESULTS

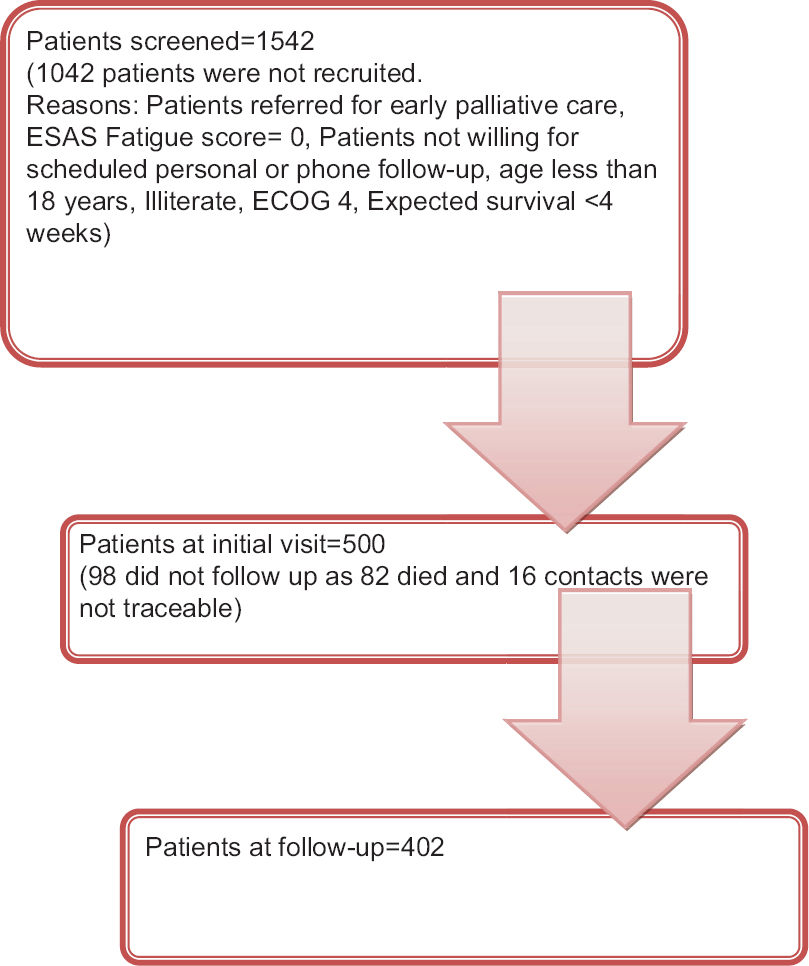

A total of 1542 new patients were referred to the Department of Palliative Medicine from January 1, 2014, to June 30, 2014. Five-hundred eligible cases participated in the study [Figure 1].

- Number of patients in the study. ESAS: Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Demographic information

At baseline assessment, 51.6% of the cases were male and had a median age of 52 years (standard deviation [SD] =13.1 years). Of these, 54.6% of them earned < Rs. 5000 (76.61 USD) per month and only 35.8% had secondary education. Most (83.4%) of the cases were married. The most common primary cancer type was head and neck cancer (23.2%), followed by gastrointestinal cancer (21.2%). Of these, 92% of the patients had stage IV cancer and 37% had more than one site of metastasis. More than half of the study cases (53.6%) had received multimodal therapy as standard treatment [Table 1].

Clinical information

Among the 500 patients at initial visit, 251 (50.2%) were of ECOG 2. Median blood hemoglobin level was 10.9 g/dl (SD = 1.9 g/dl) and 185 (37%) had low hemoglobin (≤ 10 mg/dl). Median serum albumin level was 3.5 g/dl (SD = 0.6 g/dl) and 232 (46.4%) had low albumin levels (< 3.5 mg/dl). Median body weight was 50 kg (SD = 11.2). A total of 28 cases (5.6%) were receiving step III opioids.

The scheduled time for follow-up visit was between 15 and 30 days after the first visit. The total number of patients at follow-up was 402. Among the 98 patients who did not come for the second assessment, 82 died due to progressive advanced cancer before the follow-up visit and 16 were lost to follow-up.

At the follow-up visit, 209 (43.2%) patients had ECOG 2. Median blood hemoglobin level was 10.6 g/dl (SD = 1.9 g/dl) with 139 (34.6) having low hemoglobin (≤ 10 mg/dl). Median serum albumin level was 3.5 g/dl (SD = 0.6 g/dl); 172 (42.8%) had low albumin levels (< 3.5 mg/dl). Median body weight was 50 kg (SD = 11.2). A total of 23 subjects (5.7%) were on Step III opioids [Table 2].

Fatigue

Of these, 404 patients (80.8%) reported moderate or severe fatigue (≥ 4/10)[23] at initial visit, while at follow-up, only 214 patients (53.2%) reported the same [Table 3a]. The median fatigue score at baseline was 5 (SD = 2.05) while at follow-up was 4 (SD = 2.27). Comparison of fatigue scores at baseline and follow-up by Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed statistically significant improvement (P < 0.001 and Z = −9.238) [Table 3c]. Changes in scores of other ESAS items are shown in Table 3b.

Quality of Life

The mean QoL score in EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL at the first follow-up visit (67.45) was better than that at initial assessment (51.93) with significant changes on all the items (P < 0.001) [Table 4].

Interrelationship between fatigue and Quality of Life

A linear regression model was constructed at baseline, with fatigue as the dependent variable and EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL items as independent variables. Factors found to be associated with fatigue were overall QoL (P < 0.001), emotional functioning (P < 0.001), and constipation (P = 0.038). In this predictive model, adjusted R2 = 0.607 [Table 5a].

At follow-up, a logistic regression model was constructed to measure the relationship between fatigue as a categorical-dependent variable and other factors as independent variables, by estimating probabilities, using a logistic function. From this model, the predicted improvement of fatigue was observed in 239 patients (47.8%). Change in QoL associated with physical functioning and insomnia was predictor of improvement in fatigue. The most significant change was associated with improvement in insomnia. The logistic regression model explained 43.6% (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.436) of the variance in improvement in fatigue [Table 5b].

Other factors influencing fatigue

In a correlation between fatigue and other variables at baseline, no univariate associations were found with demographic variables (age [P = 0.456], gender [P = 0.459], community [P = 0.775], province [states] [P = 0.419], family income [P = 0.258], educational status [P = 0.148], and marital status [P = 0.274]) and clinical variables (stage of disease [P = 0.218], cancer therapy received [P = 0.268], comorbidities [P = 0.877], and daily oral morphine consumption [P = 0.795]).

The factors having correlation with fatigue at baseline were clinical variables (sites of cancer [P < 0.001], sites of metastasis [P = 0.019], ECOG score [P < 0.001], and body weight [P = 0.003]) and biochemical parameters (anemia [P = 0.015], albumin levels [P < 0.001]) with P < 0.05 for each [Table 6].

For a better understanding of the multidimensional nature of fatigue, a linear regression model was constructed at baseline, with fatigue as the dependent variable and other factors as independent variables. Factors found to be associated with fatigue at baseline were demographic variables (marital status [P = 0.009]); clinical variables (ECOG [P < 0.001]); and biochemical parameters (serum albumin levels [P < 0.001]) [Table 5a].

Fatigue improved at follow-up, and a logistic regression model was constructed to find the predictors of the improvement in fatigue. The probabilities were estimated considering fatigue as a categorical-dependent variable and other factors as independent variables when using a logistic function. From this model, the predicted improvement of fatigue was observed in 239 patients (47.8%). Changes in biochemical parameters (hemoglobin and albumin level) were predictors of improvement in fatigue. The most significant change was associated with improvement in albumin level from baseline (odds ratio = 2.091 per point; P = 0.011). The logistic regression model explained 43.6% (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.436) of the variance in improvement in fatigue [Table 5b].

Patients who did not follow up (n = 98) had similar characteristics to those who did, in terms of demographic variables, body weight, and daily oral morphine consumption. However, they had lower hemoglobin (P = 0.02) and albumin (P < 0.001) levels, poorer Overall QoL (lower values indicating a lower QoL) (P < 0.001). Although it was not statistically significant, poorer scores were also found in function scales (physical functioning, and emotional functioning) and in symptom scales (dyspnea, pain, fatigue, and nausea/vomiting) of EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL [Table 7].

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide evidence that palliative care consultation for advanced cancer patients seen at an outpatient palliative care clinic in a comprehensive cancer center was associated with lessening of fatigue with improved QoL at the time of the first follow-up 2–4 weeks later.

Moderate to severe fatigue was common (80.8%) in the patients we evaluated. The severity of fatigue at the time of consultation significantly correlated with many of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL items in the predictive model, such as overall QoL (P < 0.001), emotional functioning (P < 0.001), and constipation (P = 0.038). At follow-up, an improvement in fatigue scores was observed in 47.8% of patients. Thus, the results of this study show preliminary evidence that palliative care consultation was successful in reducing the severity of fatigue. This is supported by our model which captured most of the factors associated with improvement of fatigue as indicated by adjusted R2 of 0.607. The observed improvement in fatigue score in this study is 1 point, which corresponds to the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of fatigue (MCID of fatigue item is ≥ 1 point in ESAS).[24] The factors responsible for amelioration in fatigue were improvement in biochemical parameters (hemoglobin and albumin) and betterment in QoL associated with physical functioning and insomnia as were evident in follow-up visits. When compared to baseline, patients who did not follow up had poorer parameters. These findings are similar to those seen in other studies.[12345910111213141718]

The strengths of this study are that the assessments for fatigue and other symptoms were done prospectively at both initial and subsequent follow-up visits, using validated tools in a dedicated palliative care clinic by trained palliative care physicians. The study consisted of a heterogeneous sample of patients with different cancer diagnoses, presenting at different stages of the disease process. The fatigue assessment was completed by the patients under the supervision of the physician investigator who is trained specifically in palliative care, and standardized management was provided by a specialized palliative care team in accordance with our institutional standard operating procedure (see Methods). Moreover, this study differed from other studies in its relatively large population sample size of 500 patients observed prospectively and its focus on factors associated with improvement in fatigue after an outpatient palliative care consultation. Fatigue improved despite increase in opioid prescribing as a result of consultations. This finding could be important, more so, in the Indian setting, given the strong prejudice against using opioids and the misconception that it will increase drowsiness and possibly fatigue in patients. We have shown the opposite and this is important in this context.

Fatigue has been an essential component influencing the construct of QoL. Future prospective trials are needed; however, our findings suggest that in populations similar to ours, fatigue interventions should, therefore, incorporate a multimodal interdisciplinary approach including the treatment of fatigue-related symptoms in addition to specific pharmacological and nutritional interventions for fatigue. These results are consistent with prior studies.[252627] However, female gender, which prior studies have found to be predictive of severity of fatigue,[2829] was not associated with fatigue in our study. This result could be due to the unique composition of population studied.

Our study revealed that with appropriate nutritional evaluation and provision of oral nutrition supplements and iron, our patients were able to improve their hemoglobin and albumin levels in 2–4 weeks, and also improve their fatigue levels. These are important findings given the responsibility of hospital as similar to ours in a resource-poor environment and a high patient load. The government provides a subsidy to only a limited number of patients to ensure the availability of treatment, but our nutrition clinic has devised low-cost nutrition supplements for our patients. Our hospital also provides automated short messaging services alert and phone calls from the hospital for follow-ups to ensure better compliance. We do home visits by dedicated care teams at regular intervals and involve local general practitioners in care for the patient to maintain continuity.[21] Importantly, with the recent amendment in narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances (NDPS) act, there is easy availability of opioid analgesics for pain and dyspnea control.[30] Moreover, regular counseling sessions at clinic- or home-based care by the departmental counselors might have been able to reduce the distress associated with the biopsychosocial component of fatigue in advanced cancer. This can bring about a change in patients’ perception of goals of care, values or priorities in life, which in turn brings about a change in the perception of fatigue. This is a kind of adaptation to the situation and can serve as an important defense mechanism to relieve suffering in the final stage of life as has been seen elsewhere.[1516]

In our study, 98 patients were not available for second follow-up. In these patients, the hemoglobin and albumin levels were low, severity of fatigue and other ESAS symptoms were greater, and more strikingly they had significantly lower overall QoL scores than in those who had at least one follow-up visit (the study sample) [Table 7]. This high attrition rate could be justified by the fact that the sickest patients might not have been able to participate for a follow-up which is commonly seen in other studies done in similar patient population.[2331] Further study is warranted because these screens may be predictive of those patients with a particularly short prognosis. That information would be a key for decisions about disease-directed therapy and for selecting patients for end-of-life planning.

Our study has several limitations, the most important of which was its lack of patients in the setting other than an outpatient palliative care clinic. Furthermore, because of our concern that patients with advanced cancer might be unable to complete multiple questionnaires, we elected to use only the ESAS scale. No additional questionnaire for assessing derangement of cognitive function was used to assess the patients. Although the study was supervised by the investigator, minor errors arising from reduced cognitive ability cannot be ruled out. Symptom-specific instruments (e.g. brief fatigue inventory) were not used in the palliative care setting as they were considered even more challenging to frail patients. Another limitation is the use of single-item measure to assess physical and emotional symptoms using ESAS. However, prior studies have shown that ESAS items and other single item questionnaires correlate well with multi-item symptom assessment tools.[3233343536] Although, in the vast majority cases, patients complete the ESAS by themselves in the outpatient setting, there is a possibility that in the most fatigued patients, the caregiver could have introduced the bias by assisting the patients. More research is necessary to address this possibility. This study also did not assess other well-known factors that may contribute to fatigue such as inflammatory biomarkers, which play an important role in fatigue causation.[373839] Some of the statistically significant associations in this study may be a result of multiple regression analyses. Future prospective, randomized controlled trials of larger sample sizes with no fatigue as another cohort are required to validate these important findings. Another important aspect to explore will be the effect of dietary supplementation on betterment of biochemical parameters associated with fatigue and QoL scores. These can have strong economic implications in resource-poor settings. Furthermore, compliance with medications in serial follow-ups can be a predictor of durable response which needs further research.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggested that our Indian patients with advanced cancer had moderate to severe fatigue which could be improved with comprehensive palliative care, nutritional supplementation, and provision of opioids for those who were dyspneic or in pain, all of which are the standard palliative care procedures in our outpatient palliative care clinic. Fatigue was associated with worsening overall QoL, emotional functioning, and constipation. Improvement in physical functioning and insomnia lessened fatigue.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all staff members of the Department of Palliative Medicine at Tata Memorial Centre, who have contributed to the materialization of this work. We would also like to thank the patients and caregivers who gave us their consent, valuable time, and energy in carrying out the study.

REFERENCES

- Cancer-related fatigue: Inevitable, unimportant and untreatable? Results of a multi-centre patient survey. Cancer Fatigue Forum. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:971-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue, psychological distress, coping and quality of life in patients with uterine cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:205-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: Results of a tripart assessment survey. The fatigue coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):4-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring quality of life in palliative care. Semin Oncol. 1995;22(2 Suppl 3):73-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life: What is it? How should it be measured. Oncology (Williston Park). 1988;2:69-76, 64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and correlates of fatigue after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1689-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: Characteristics, course, and correlates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:233-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue, depression and quality of life in cancer patients: How are they related? Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:101-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of dyspnea, pain, and fatigue on daily life activities in ambulatory patients with advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:417-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of hemoglobin levels on fatigue and quality of life in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:965-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- The challenge of response shift for quality-of-life-based clinical oncology research. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:747-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer-related fatigue: “It's so much more than just being tired”. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:117-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between cancer-related fatigue and patient satisfaction with quality of life in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:40-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue dimensions in patients with advanced cancer in relation to time of survival and quality of life. Palliat Med. 2009;23:171-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in cancer patients receiving palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2010;16:36-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of advanced cancer. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2010;31:121-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tata Memorial Centre. 2014. Tata Memorial Centre Annual Report 2013-14. Mumbai: Tata Memorial Centre; Available from: https://www.tmc.gov.in/PDF/TataAR_English2014.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2011. In: IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with the severity and improvement of fatigue in patients with advanced cancer presenting to an outpatient palliative care clinic. BMC Palliat Care. 2012;11:16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Minimal clinically important differences in the Edmonton symptom assessment scale in cancer patients: A prospective, multicenter study. Cancer. 2015;121:3027-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidimensional independent predictors of cancer-related fatigue. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:604-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- The level of haemoglobin in anaemic cancer patients correlates positively with quality of life. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1243-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship of hemoglobin levels to fatigue and cognitive functioning among cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:7-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women experience higher levels of fatigue than men at the end of life: A longitudinal home palliative care study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:389-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94:528-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Passage of the Narcotic Dr ug and Psychotropic Substances Amendment, White Paper. Available from: http://www.egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2014/158504.pdf

- Immune system to brain signaling: Neuropsychopharmacological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:226-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between fatigue and other cancer-related symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1125-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical relevance of single item quality of life indicators in cancer clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1156-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:20-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Edmonton symptom assessment system as a screening tool for depression and anxiety. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:296-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of single-item linear analog scale assessment of quality of life in neuro-oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:628-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroendocrine-immune mechanisms of behavioral comorbidities in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:971-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Higher levels of fatigue are associated with higher CRP levels in disease-free breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:136-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: Do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3517-22.

- [Google Scholar]