Translate this page into:

Healthcare Workers Knowledge and Attitude Toward Palliative Care in an Emerging Tertiary Centre in South-West Nigeria

Address for correspondence: Dr. Joseph O. Fadare; E-mail: jofadare@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Palliative care is an emerging area of medicine with potential to affect positively many chronically ill patients. This study investigated the knowledge and attitude of healthcare workers in a tertiary level hospital in Nigeria where a palliative care unit is being established.

Material and Methods:

The study was a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study carried out among healthcare workers in Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, south-west Nigeria. The questionnaire had sections about definition of palliative care, its philosophy, communication issues, medications, and contexts about its practice. The information obtained from the questionnaire was coded, entered, and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 19.

Results:

A total of 170 questionnaires were returned within the stipulated time frame with response rate of 66.7%. Majority, (135, 86%) respondents felt palliative care was about the active management of the dying while 70.5% of respondents equated palliative care to pain management. Regarding the philosophy of palliative care, 70 (57.9%) thought that it affirms life while 116 (78.4%) felt palliative care recognizes dying as a normal process. One hundred and twenty-two (78.7%) respondents were of the opinion that all dying patients would require palliative care. The patient should be told about the prognosis according to 122 (83%) respondents and not doing so could lead to lack of trust (85%). Regarding the area of opioid use in palliative care, 76% of respondents agreed that morphine improves the quality of life of patients.

Conclusion:

There are plausible gaps in the knowledge of the healthcare workers in the area of palliative care. Interventions are needed to improve their capacity.

Keywords

Healthcare workers

Knowledge

Palliative care

Perception

Oncology

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care according to the World Health Organization (WHO) is the active total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment. Control of pain, of other symptoms, and of psychological, social, and spiritual problems is paramount. The goal of palliative care is achievement of best quality of life for patients and their families.[1] Palliative care aims to affirm life while regarding dying as a normal process, to provide support to enable patients to live as actively as possible until death and to offer support to the family during the patient's illness and in their bereavement.[2] Though palliative care has been somewhat established in many developed countries of the world, it is an emerging medical specialty in many developing ones with establishment of palliative care centers in India, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon.[345] In Nigeria, palliative care is still in its early stage of development with the establishment of the first palliative care centre in the oldest teaching and tertiary hospital in 2003.[6] The frequency of chronic noncommunicable diseases as major cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries has also emphasized the need for professionals in the healthcare sector to acquire knowledge and develop skills in palliative care.

The knowledge and attitude of doctors, pharmacists, nurses, and other healthcare workers toward palliative care and end of life matters had been explored in studies from Pakistan, Lebanon, India, and Turkey.[78910] The main objective of this study was to explore the knowledge and attitude of workers in a Nigerian tertiary healthcare facility about palliative care and to inform where gap in knowledge or understanding may exist.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting

The study was carried out among healthcare workers of the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, a 300-bedded tertiary care facility located in Ado-Ekiti, south-west Nigeria. This centre has specialists in Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, Surgery, Psychiatry, Pediatrics, Community Medicine, Anesthesia, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and Pathology. It also has a large component of Nursing, Pharmacy, and other allied healthcare workers.

Design

The study was a cross-sectional questionnaire-based carried out during the first week of April 2013. The study instrument (questionnaire) was adapted from one used in a previous study.[11] pretested among 10 healthcare workers of the hospital and necessary adjustments made before being administered to the participants.

Sampling procedure

The sample size for the study was calculated using the following assumptions: 95% confidence interval, margin of error (5%), level of response (50%), and population of 400. A sample size of 197 was calculated and this was increased to 255 to accommodate possible nonresponders. The sampling of the different professional classes (Nurses and Doctors) was done proportionally according to their respective populations in the hospital with 120, 100, 20, 10, and 5 questionnaires were distributed to the Nurses, Doctors, Pharmacists, Social Workers, and Clinical Psychologists, respectively. The sample sizes of the professional classes should be sufficient enough to bring out the differences in response between the aforementioned groups, a basic hypothesis of this study. Convenience sampling was used as questionnaires were administered to the healthcare workers during various departmental activities. The questionnaire apart from the socio-demographic profile of respondents had sections about the definition of palliative care, its philosophy, communication issues, nonpain symptoms of palliative care, medication use in palliative care, and context of application. All questions or statements were close ended with three options (Yes, No, and Don’t Know). Hard copies of the questionnaires were distributed to the healthcare workers through various unit heads and those completed and returned within the time frame of one week were used for data analysis.

Data analysis

The information obtained from the questionnaire was coded, entered, and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 19. Analysis was done using descriptive statistics to obtain the general characteristics of the study participants. Chi-square was employed to determine the level of significance of groups of categorical variables such as professional cadre, duration of practice, and gender with P values less than 0.05 considered significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Hospital Research Ethics Committee before the commencement of the study.

RESULT

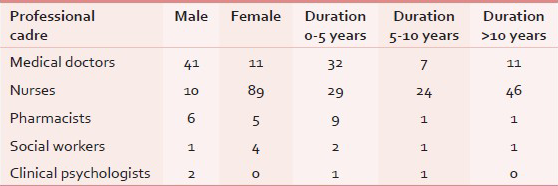

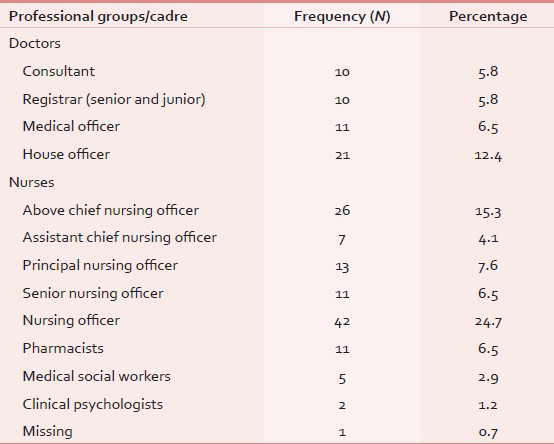

A total of 170 questionnaires were completed and returned within the stipulated time frame with a response rate of 66.7%. The response rate was different among the professional groups with Social Workers (100%), Nurses (83.3%), Doctors (52%), Pharmacists (55%), and Clinical Psychologists (40%). Female respondents constituted the majority with 110 (64.7%) and the mean age of all participants was 36.6 ± 9.3 years. The demographics of different professional groups and duration of practice are shown in Table 1 while the distribution of Doctors and Nurses according to their cadre is shown in Table 2.

The majority (70.5%) of the respondents understood palliative care to be about pain medicine, 47.9% thought it to be geriatric medicine while 135 (82.3%) respondents felt palliative care is about the active care of the dying. Regarding the philosophy of palliative care, 70 (57.9%) thought that it affirms life while 116 (78.4%) felt palliative care recognizes dying as a normal process. Only 8 respondents felt that applying palliative care hastens death and 108 (77.7%) believe that it aims to prolong life. Regarding the group of patients requiring palliative care, 122 (78.7%) respondents were of the opinion that all dying patients would require palliative care while 132 (93%) knew that patients with metastatic cancers are candidates for this end of life care. Most of the respondents were also aware that palliative care could be applicable for conditions like end stage organ failure (72.6%) and rheumatoid arthritis (82.5%). The nonpain symptoms (delirium, constipation, vomiting, and breathlessness) common in patients requiring palliative care were recognized by 76.8%, 60.2%, 69.7%, and 80.5%, respectively. Regarding discussion of the prognosis, 122 (83%) respondents believe that the patient should be told the truth and that not doing so could lead to lack of trust (85%). Regarding the membership of the palliative care team, 91.7%, 94.7%, 96.7%, and 91.8% of respondents voted in favor of medical social workers, nurses, medical doctors, and pharmacists, respectively. Religious leaders and occupational therapists were also accepted for membership by 88.4% and 75% of respondents, respectively. Regarding their knowledge about advance directives, 132 (84.6%) respondents got the correct definition while only 62.4% knew that the term is synonymous with “living will”.

Regarding the area of opioid use in palliative care, 76% of respondents agreed that morphine improves the quality of life of patients while only 11.3% believe that the use of morphine will lead to death. Majority of respondents erroneously believe that morphine and pentazocine would relieve all kinds of pain (73.9% and 66.2%, respectively). The components of a good death according to respondents were pain and symptomatic management 139 (92.7%), clear decision making 121 (90.3%), and preparation for death 135 (90.6%). A total of 149 (93.7%) respondents agreed that there is a need for the hospital to have a palliative care team as soon as possible.

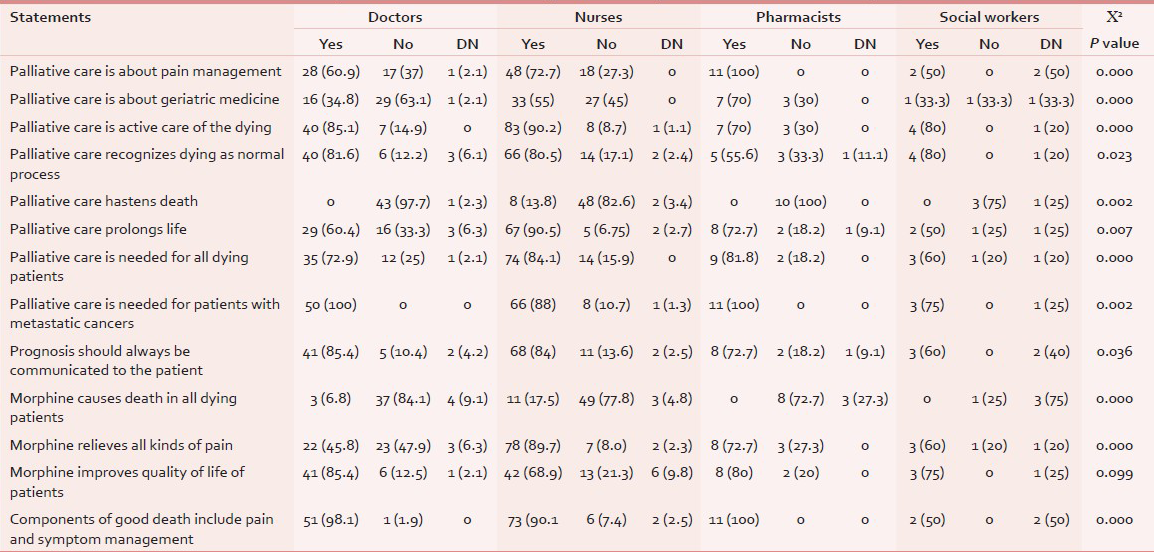

The association between the different professional groups and knowledge about various themes of palliative care was also explored [Table 3]. The pharmacists were more likely to correctly define palliative care as being related to pain management than doctors and nurses respectively. Doctors were also less likely to fallaciously define palliative care as geriatric medicine in comparison to pharmacists and nurses. Regarding the association of the different professional classes and knowledge of the philosophy of palliative care, nurses were more likely than doctors to think that the aim of palliative care is to prolong life. The responses regarding the use of morphine in palliative care showed that more nurses erroneously believed that morphine relieves all kinds of pain. There was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.732) in the duration of practice and the knowledge base of respondents in the area of definition of palliative care.

DISCUSSION

From the above results, it is clear that the knowledge of respondents about the different aspects of palliative care varied. The knowledge of the respondents about the definition and philosophy of palliative care was very good while their responses regarding opioid use in palliative care and category of patients that would require palliative care were less concise. The preponderance of female respondents in this study could be explained by relatively large number of female nurses among the study population. A similar study by Prem et al. on nurse's knowledge about palliative care also had female preponderance of 89%.[12] Regarding the definition of palliative care, 70.5% of our respondents agreed that it could be defined as such while 86% also agreed that active care of the dying was a correct option. In a similar study by Jahan et al., 87.7% of participants were of the same opinion, while 60.3% felt that palliative care is the active care of the dying.[11] In a study carried out in Lebanon, 95.1% of participating medical doctors and 84.6% of the nurses were of the opinion that palliative care affirms life and regarded dying as a normal process.[8] This result is at variance from the outcome of our study where only 57.9% and 78.4% answered in the affirmative regarding these two components of the philosophy of palliative care. The differences in responses from the two studies could be due to availability or lack of training opportunities in palliative care at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels in the countries where these studies were carried out. In an earlier cited study among medical undergraduates in Lebanon, 34.2% felt that palliative care is required in all dying patients. In this study, 78.7% of respondents erroneously answered this same question; a difference that could be due to training deficiencies among the respondents. Majority (93%) of our respondents agreed that palliative care was required for patients with metastatic cancers, similar to 93.2% and slightly higher than 74% found in other similar studies.[7891011] This convergence of opinion is most likely due to the long standing belief that palliative care is needed only in oncology patients. With the emergence of other chronic communicable diseases, most especially, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and noncommunicable conditions (osteoarthritis, organ failure and Alzheimer's disease), the scope of palliative care has increased.[12] Regarding communication of prognosis to patients, 83% of respondents agreed that this was necessary, similar to 91.8%, 83.9%, and 83.1% found among medical undergraduates, nurses, and medical doctors in various studies.[891011] The knowledge about advanced directives among respondents in our study was also very encouraging with 84.6% choosing the correct definition despite the fact that this is a new concept in our daily clinical practice. Regarding the respondents’ knowledge about use of opioids in palliative care, this study found some misconceptions; 73.9% believed that morphine will relieve all kinds of pains, 11.0% of respondents believe that morphine would cause death while only 41.3% knew that morphine could improve breathlessness in heart failure. This is not surprising as many studies from different regions have shown that physicians and nurses have issues regarding the use of morphine in oncology patients.[13141516] Regarding components of a good death, majority of our respondents answered in the affirmative, an outcome similar to results from a previously cited study.[11] From the results of this study, future research in the area of palliative care in Nigeria should be directed at issues of communication (truth telling especially regarding prognosis) and opioid analgesic use among oncology patients. The main implication of this study for practice is the need for a better understanding of use of opioid analgesia for patients with terminal diseases. The study also revealed the need for a review of curriculum of healthcare workers to include the core themes of palliative care. While the results of our study may not be generalizable for the whole country, it could be representative for similar tertiary institutions in Nigeria and other countries alike.

Study limitations

Limitations arising from the study's design and methodology would include those associated in general with questionnaire-based studies. They include bias of the respondents toward certain issues, inaccurate responses, and incidence of skipped questions. The relatively low response rate of medical doctors and the low number of other allied healthcare workers were additional limitations of this study.

CONCLUSION

Our study clearly showed the gaps in the knowledge of healthcare workers in the area of palliative care. There is a need to introduce or reinforce the study of palliative care in the curriculum of medical doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare workers both at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Geneva: WHO; 2002.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care Explained. National Council for Palliative Care UK. 2006. Available from: http://www.ncpc.org.uk

- [Google Scholar]

- An experience with 156 patients attending a newly organized pain and palliative care clinic in a tertiary hospital. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:293-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care in Saudi Arabia: A brief history. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2003;17:45-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Implementation of palliative care in Lebanon: Past, present, and future. J Med Liban. 2008;56:70-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care in Enugu, Nigeria: Challenges to a new practice. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:131-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Awareness of palliative medicine among Pakistani doctors: A survey. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:195-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care in Lebanon: Knowledge, attitudes and practices of physicians and nurses. J Med Liban. 2007;55:121-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey of palliative care concepts among medical interns in India. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:654-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Turkish healthcare professionals’ views on palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2012;28:267-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perception of undergraduate medical students in clinical years regarding palliative care. Middle East J Age Ageing. 2013;10:2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer pain: Knowledge and attitudes of physicians in Israel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:266-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphinofobia: The situation among the general population and health care professionals in North-Eastern Portugal. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;22(9):15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: A national survey of Italian oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:272-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of the residents at King Abdul-Aziz University Hospital (KAAUH) about palliative care. J Family Community Med. 2012;19:194-7.

- [Google Scholar]