Translate this page into:

Integration of Early Specialist Palliative Care in Cancer Care: Survey of Oncologists, Oncology Nurses, and Patients

Address for correspondence: Dr. Naveen Salins; E-mail: naveensalins@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Palliative care is usually delivered late in the course of illness trajectory. This precludes patients on active disease modifying treatment from receiving the benefit of palliative care intervention. A survey was conducted to know the opinion of oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients about the role of early specialist palliative care in cancer.

Methods:

A nonrandomized descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary cancer care center in India. Thirty oncologists, sixty oncology nurses, and sixty patients were surveyed.

Results:

Improvement in symptom control was appreciated by oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients with respect to pain (Z = −4.10, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.84, P = 0.001), (Z = −6.20, P = 0.001); nausea and vomiting (Z = −3.75, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.3, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.1, P = 0.001); constipation (Z = −3.29, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.96, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.49, P = 0.001); breathlessness (Z = −3.57, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.03, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.99, P = 0.001); and restlessness (Z = −3.68, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.23, P = 0.001), (Z = −3.22, P = 0.001). Improvement in end-of-life care management was appreciated by oncologists and oncology nurses with respect to communication of prognosis (Z = −4.04, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.20, P = 0.001); discussion on limitation of life-sustaining treatment (Z = −3.68, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.53, P = 0.001); end-of-life symptom management (Z = −4.17, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.59, P = 0.001); perimortem care (Z = −3.86, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.80, P = 0.001); and bereavement support (Z = −3-80, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.95, P = 0.001). Improvement in health-related communication was appreciated by oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients with respect to communicating health related information in a sensitive manner (Z = −3.74, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.47, P = 0.001), (Z = −6.12, P = 0.001); conducting family meeting (Z = −3.12, P = 0.002), (Z = −4.60, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.90, P = 0.001); discussing goals of care (Z = −3.43, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.49, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.61, P = 0.001); maintaining hope (Z = −3.22, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.85, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.61, P = 0.001); and resolution of conflict (Z = −3.56, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.29, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.28, P = 0.001). Patients appreciated improvement in continuity of care with respect to discharge planning (Z = −6.12, P = 0.001), optimal supply of essential symptom control medications on discharge (Z = −6.32, P = 0.001), follow-up plan (Z = −6.40, P = 0.001), after hours telephonic support (Z = −6.31, P = 0.001), and preferred place of care (Z = −6.28, P = 0.001).

Conclusion:

Oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients felt that integration of early specialist palliative care in cancer improves symptom control, end-of-life care, health-related communication, and continuity of care. The perceptions of benefit of the palliative care intervention in the components surveyed, differed among the three groups.

Keywords

Cancer

Early specialist palliative care

Survey

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, palliative care is delivered late in the course of the illness trajectory.[12] This approach excludes the benefit of palliative care to many patients receiving active anticancer therapy.[34] In patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer, early palliative care referral is associated with improvement in quality of life and survival.[5] Over the last few years, specialty of palliative care has expanded and surpassed the conventional hospice model of care to integrated simultaneous and shared model of care where patients are receiving specialist palliative care input alongside active disease-directed treatment. This enables symptom control, better health-related communications, and empowers patients and families in shared medical decision-making.[6] Palliative care is an essential care for all seriously ill patients. Hence, it is important to integrate it in all active medical care processes and integrate teaching of palliative care in health curriculum.[78] American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has emphasized the integration of palliative care services as one of ASCOs accomplishments and has included it as part of its “Vision for Comprehensive Cancer Care 2020.”[9] The National Comprehensive Cancer Care Network's palliative care guidelines recommend screening of all patients’ for palliative care issues during initial oncology consultation and subsequently at clinically relevant times.[10] A study conducted on these lines showed that 7-17% of patients during initial consultation had palliative care needs and 13% of them needed specialist palliative care referral.[11] In this study, a survey was conducted to know the opinion of oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients about the role of early specialist palliative care in symptom control, continuity of care, health-related communication, and end-of-life care.

METHODS

Design

This was a nonrandomized descriptive cross-sectional study conducted at a tertiary cancer care center in India. The aim of this study was to know the opinion of oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients about the role of integration of early specialist palliative care in a tertiary cancer care center in India. The primary objective was to know the role of integration of early specialist palliative care in symptom control. The secondary objectives were to know the role of integration of early specialist palliative care in continuity of care, health-related communication, and end-of-life care.

Setting

The study was conducted in a tertiary cancer care setting in India. The study was conducted from January 2013 to July 2013. The specialist palliative care intervention was provided, as a multidisciplinary team comprising of palliative medicine physicians, palliative care nurses, medical social workers, complementary and alternative medicine specialists, yoga therapists, occupational and physiotherapists, psycho-oncologists, and dieticians. The integrated approach enabled access to competent person-centered care for patients within the environs of a tertiary oncology care center. It aimed at caring for the patients, right from diagnosis of cancer through the illness trajectory including the end-of-life phase. In a cancer care setting where all modalities of treatment are directed at the disease, the integrated palliative approach acknowledged the needs of the “person” who is having the disease and hence it provided a “person-centered” approach. Patients were referred to palliative care early, needs of the person were assessed, symptoms were evaluated early and managed, health-care related communications were completed, and continuity of care was provided. Integrated palliative approach facilitated a smooth transition of care process from disease-directed therapy to holistic person-centered management.

Study population

Thirty oncologists, sixty oncology nurses, and sixty patients were surveyed. Among the thirty oncologists included in the survey, ten were medical oncologists, ten were radiation oncologists, and ten were surgical oncologists. All the oncologists included in the study were practicing consultants. Among the sixty-oncology nurses included in the survey, forty were ward oncology nurses, ten were day care chemotherapy nurses, and ten were oncology nurse practitioners. All patients aged 18 years and above, with proven cancer diagnosis, receiving cancer-directed treatment, and simultaneously receiving specialist palliative care input for at least 30 days from the time of referral were included in the study. Patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 4 and patients not consenting or not able to complete the study questionnaire, patients needing hospice transfer or Intensive Care Unit admission during the study period were excluded from the study.

Survey questionnaire

The survey was conducted using a 5-point Likert scale-based questionnaire. Each survey questionnaire had three sections, and each section had five items. Doctors and nurses completed a common questionnaire. The broad sections were symptom control, health-related communication, and end-of-life care. The questionnaire for patients had continuity of care section instead of the end-of-life care section [Appendices 1 and 2].

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 for windows (SPSS Version 20.0 for Windows IBM Chicago). Data were analyzed for within group comparisons following intervention using nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank tests and between groups using Mann-Whitney tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests.

RESULTS

Symptom control

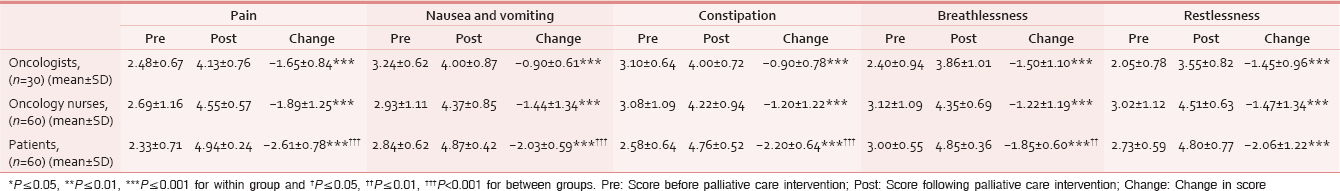

All thirty oncologists, sixty oncology nurses, and sixty patients completed this section. Significant improvement in symptom control following palliative care intervention was appreciated by oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients with respect to pain (Z = −4.10, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.84, P = 0.001), (Z = −6.20, P = 0.001); nausea and vomiting (Z = −3.75, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.3, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.1, P = 0.001); constipation (Z = −3.29, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.96, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.49, P = 0.001); breathlessness (Z = −3.57, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.03, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.99, P = 0.001); and restlessness (Z = −3.68, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.23, P = 0.001), (Z = −3.22, P = 0.001) on Wilcoxon signed rank test [Table 1].

Comparison of impact among the groups using Kruskal-Wallis (Chi-square) test showed patients appreciated palliative care interventions more than oncologists and oncology nurses with respect to management of pain (χ2 = 19.4, P = 0. 001), nausea and vomiting (χ2 = 19.3, P = 0. 001), constipation (χ2 = 21.9, P = 0. 001), breathlessness (χ2 = 9. 3, P = 0. 009), and restlessness (χ2 = 4.86, P = 0. 08) [Table 1 and Figure 1].

- Waterfall chart showing impact of early specialist palliative care intervention on symptom control before and after early specialist palliative care intervention

End-of-life care

Twenty-four oncologists and 52 oncology nurses completed this section. Significant improvement in end-of-life care management following palliative care intervention was appreciated by oncologists and oncology nurses with respect to communication of prognosis (Z = −4.04, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.20, P = 0.001); discussion on limitation of life-sustaining treatment (Z = −3.68, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.53, P = 0.001); end-of-life symptom management (Z = −4.17, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.59, P = 0.001); perimortem care (Z = −3.86, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.80, P = 0.001); and bereavement support (Z = −3-80, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.95, P = 0.001) on Wilcoxon signed rank test [Table 2].

Comparison of impact among the groups using Mann-Whitney U-test showed that oncologists appreciated palliative care interventions in end-of-life care management more than oncology nurses with respect to discussion on limitation of life-sustaining treatment (Z = −2.57, P = 0.01), end-of-life symptom management (Z = −2.38, P = 0.01), perimortem care (Z = −2.64, P = 0.008), and bereavement support (Z = −1.97, P = 0.04) [Table 2 and Figure 2].

- Waterfall chart showing impact of early specialist palliative care intervention on end-of-life management before and after early specialist palliative care intervention

Health-related communication

Twenty-four oncologists, 54 oncology nurses, and fifty patients completed this section. Significant improvement in health-related communication following palliative care intervention was appreciated by doctors, nurses, and patients with respect to communicating health-related information in a sensitive manner (Z = −3.74, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.47, P = 0.001), (Z = −6.12, P = 0.001); conducting family meeting (Z = −3.12, P = 0.002), (Z = −4.60, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.90, P = 0.001); discussing goals of care (Z = −3.43, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.49, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.61, P = 0.001); maintaining hope (Z = −3.22, P = 0.001), (Z = −4.85, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.61, P = 0.001); and resolution of conflict (Z = −3.56, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.29, P = 0.001), (Z = −5.28, P = 0.001) on Wilcoxon signed rank test [Table 3 and Figure 3].

- Waterfall chart showing impact of early specialist palliative care intervention on health-related communication, before and after early specialist palliative care intervention

Comparison of impact between groups showed significant improvement seen in health-related communication with respect to communicating health-related information in a sensitive manner (Z = −2.96, P = 0.003), conducting family meeting (Z = −3.94, P = 0.001), discussing goals of care (Z = −3.76, P = 0.001), and maintaining hope (Z = −2.20, P = 0.02) was appreciated by patients when compared to oncologists on Mann-Whitney U-test. Comparison between patients and oncology nurses showed that health-related communication such as communicating health-related information in a sensitive manner (Z = −3.43, P = 0.001), conducting family meetings (Z = −4.68, P = 0.001), and discussion of goals of care (Z = −2.96, P = 0.003) was better appreciated by patients compared to oncology nurses on Mann-Whitney U-test. There were no significant differences between oncologists and oncology nurses group [Table 3].

Continuity of care

All sixty patients completed this section. According to patients, availability of early specialist care improved continuity of care with respect to discharge planning (Z = −6.12, P = 0.001), optimal supply of essential symptom control medications on discharge (Z = −6.32, P = 0.001), follow-up date and follow-up plan (Z = −6.40, P = 0.001), after hours telephonic support (Z = −6.31, P = 0.001), and preferred place of care (Z = −6.28, P = 0.001) on Wilcoxon signed rank test [Table 4].

DISCUSSION

Worldwide, studies conducted on the role of integrated specialist palliative care in cancer care centers have shown improved symptom management, better psychological support to patients and families, planned discharge, decreased in-hospital mortality, higher degrees of satisfaction among patients and their families, better insight among patients and families about diagnosis and prognosis, discussion of goals of care, and documentation of advanced directives.[12131415] ASCOs provisional clinical opinion on the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care states that combined standard oncology care and palliative care should be considered early in the course of illness for any patient with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden.[16]

Review of evidence on the role of early specialist palliative care intervention on symptom control shows that early specialist palliative care improves physical symptoms.[171819] The randomized control trial (RCT) by Zimmerman et al.[17] and the RCT by Rugno et al.[18] showed improvement in physical symptoms. These findings were supported by a retrospective review of medical records by Kwon et al.[19] Two RCTs, ENABLE II,[20] and ENABLE III[21] did not show any improvement in symptoms. This was because specialist palliative care interventions in these studies were education interventions with very limited specialist palliative clinical care and management of symptoms. A mixed method (RCT and qualitative) study in surgical oncology patients showed no perceived improvement in symptoms with early specialist palliative care intervention.[22] However, the patients in the study group felt reassured knowing pain and palliative care services were available. In our study, oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients felt that early specialist palliative care interventions improved pain, nausea and vomiting, constipation, breathlessness, and restlessness. With regard to symptom management, patients appreciated specialist palliative care interventions more than oncologists and oncology nurses.

Review of evidence on the role of early specialist palliative care in end-of-life care management shows that specialist palliative care intervention improves end-of-life care outcomes.[52324] In the RCT by Temel et al.,[5] the early specialist palliative care group received less aggressive medical interventions at end-of-life and higher rates of documentation of end-of-life preferences. These findings were supported by studies by Hui et al.[23] and Wiese et al.[24] This could be because earlier palliative care referral provides room for a longer therapeutic relationship, discussion of goals of care, and advanced care planning, which could facilitate improved end-of-life care outcomes. In our study, according to oncologists and oncology nurses, specialist palliative care interventions improved communication of prognosis, discussions on limitation of life-sustaining treatment, end-of-life symptom management, perimortem care, and bereavement support. With regard to end-of-life care, oncologists appreciated specialist palliative care interventions more than oncology nurses.

Review of evidence on the role of early specialist palliative care in health-related communication shows that specialist palliative care intervention improves health-related communication.[18] Oncologists often hesitate to discuss sensitive health-related communications such as cessation of disease-directed treatment, change in goals of care, prognostication, resuscitation, and end-of-life care. This is due to the perceived feeling that these communications could make patients and families depressed, takes their hope away, reduce patient survival, and may not be culturally appropriate.[25] In our study, oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients felt that specialist palliative care interventions improved communication of health-related information in a sensitive manner, family meetings being conducted, discussions of goals of care, and resolution of conflicts. With regard to health-related communication, patients appreciated specialist palliative care interventions more than oncologists and oncology nurses.

Review of evidence on the role of early specialist palliative care in continuity of care has shown that early specialist palliative cares decrease hospital admission, emergency department visits, and length of hospital stay. It promotes early hospice referral and increases the duration of hospice stay.[51923262728] In our studies, patients felt that specialist palliative care intervention facilitated planned discharge, adequate quantities of symptom control medications being provided on discharge, clear follow-up plans, after-hours telephonic support, and discussion of preference of place of care and overall better continuity of care.

CONCLUSION

Survey of oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients shows that oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients felt that integration of early specialist palliative care in a tertiary cancer center in India improves symptom control, end-of-life care, health-related communication, and continuity of care. There were, however, differences among the groups regarding the relative benefits of palliative care inputs in the different surveyed outcomes.

Limitations of this study

This was a cross-sectional study that sourced the opinions of oncologists, oncology nurses, and patients about the role of early specialist palliative care in cancer. True benefit of specialist palliative care intervention can only be known through a well-conducted randomized controlled trial. The study was conducted through a Likert scale based questionnaire, and validated instruments were not used. Only four outcomes of palliative care interventions were examined, and other outcomes of palliative care interventions were not examined. Although this study was a nonrandomized survey, with a relatively small sample size, it is the first of its kind that examined the role of integration of early specialist palliative care in an Indian cancer care setting.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Phase II study of an outpatient palliative care intervention in patients with metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:206-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenges in palliative care research; recruitment, attrition and compliance: Experience from a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med. 1999;13:299-310.

- [Google Scholar]

- Late referrals to specialized palliative care service in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2637-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: A systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299:1698-709.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Generalist plus specialist palliative care – Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- An integrated biopsychosocial approach to palliative care training of medical students. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:365-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinically based palliative care training is needed urgently for all oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4042-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps – From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for Palliative Care: Implementation of the NCCN Guideline at a Comprehensive Cancer Center (418-A) 2012:387-8.

- Palliative care in the outpatient oncology setting: Evaluation of a practical set of referral criteria. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:366-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: Clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2008-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospital based palliative care teams improve the insight of cancer patients into their disease. Palliat Med. 2004;18:46-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospital based palliative care teams improve the symptoms of cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2003;17:498-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care consultations: How do they impact the care of hospitalized patients? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:166-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early integration of palliative care facilitates the discontinuation of anticancer treatment in women with advanced breast or gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135:249-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics of cancer patients referred early to supportive and palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:148-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:741-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care outcomes in surgical oncology patients with advanced malignancies: A mixed methods approach. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:405-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- International recommendations for outpatient palliative care and prehospital palliative emergencies – A prospective questionnaire-based investigation. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2715-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:394-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost-effectiveness of early palliative care intervention in recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130:426-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early admission to community-based palliative care reduces use of emergency departments in the ninety days before death. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:774-9.

- [Google Scholar]

APPENDICES: Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire for doctors and nurses

Appendix 2: Survey questionnaire for patients