Translate this page into:

Quality of Life and Neuropathic Pain in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: A Comparative Analysis of Patients in Palliative Care Wards Versus Those in General Wards

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sungur Ulas, Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Ege University Faculty of Medicine, 35100 Bornova, Izmir, Turkey. E-mail: sungurulasailem@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

While the survival of cancer patients is prolonged due to the development of new treatment strategies and advancing technologies, the prevalence of symptoms such as neuropathic pain affecting the quality of life is also increasing.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to determine the relationship between neuropathic pain (NP) and quality of life in hospitalized cancer patients and to compare patients in general wards and those in palliative care wards in terms of NP and quality of life.

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 156 patients, 53 cancer patients hospitalized in the palliative care unit and 103 cancer patients hospitalized in general wards, were included in the study. The Douleur Neuropathic 4 test was used for NP assessment, and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD), Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), and Short Form of Brief Pain Inventory (SF-BPI) were used for assessing pain characteristics and their effects on quality of life.

Results:

NP was present in 39.7% of cases and nociceptive pain (NP) was present in 32.7% of cases. There were no complaints of pain 27.6% of cases. The patients with no pain complaint were excluded, 54.9% of the patients had NP and 45.1% had NS. The scores of BFI, HAD-depression, ESAS overall, and ESAS tiredness were significantly lower in patients with NP treated general wards compared to patients with NP in the palliative care wards (P < 0.05). Cancer patients with NP in general wards had significantly higher scores of SF-BPI effect, SF-BPI severity, ESAS overall, ESAS pain, ESAS tiredness, ESAS nausea, ESAS appetite, and ESAS well-being as compared to those of general cancer patients with NS (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Since there was a homogeneous distribution among the groups in terms of both cancer treatment and pain management, we directly related the deterioration of the patients’ quality of life to NP.

Keywords

Cancer

neuropathic pain

pain

palliative care

quality of life

treatment

INTRODUCTION

Length of survival has been improved in cancer patients with research and new treatment methods in the recent years, but the frequency of various symptoms, especially pain, has also increased.[1] Ninety percent of cancer patients suffer from pain at some point during their illness, and it affects their quality of life negatively.[23] On the other hand, 39% of cancer patients suffer from neuropathic pain (NP).[4] Studies have shown that NP in cancer patients affects daily life more severely than nociceptive pain (NS) and that improvement in the quality of life is more pronounced after its treatment.[567]

Although adjuvant analgesics are recommended at the first stage and the opioids later in treatment guidelines,[8] it has been often preferred in clinical practice to use adjuvant analgesics in addition to high-dose opioid therapy[1] since pure NA is rare.[9] Treatment options have often limited efficacy and about 50% of patients do not receive adequate analgesic treatment due to various reasons including drug-related side effects.[10] The inability to provide effective pain treatment in cancer patients is one of the most frequently discussed difficulties in the literature.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no previous study evaluating cancer patients who do and do not require palliative care treatment. Recently, one study investigating the effect of the NA on the quality of life and the use of medication in cancer patients has been published.[11] When considering the clinical characteristics of the palliative care unit and hospitalized patients, a greater impact on quality of life may be expected.[1213] However, pain status of these patients and its impact level on daily life can be a guide for the treatment.

The primary purpose of our study was to establish the relationship between NP and the quality of life and the use of medication in cancer patients. The secondary aim was to compare the patients from palliative care and oncology units in terms of NP and the quality of life.

METHODS

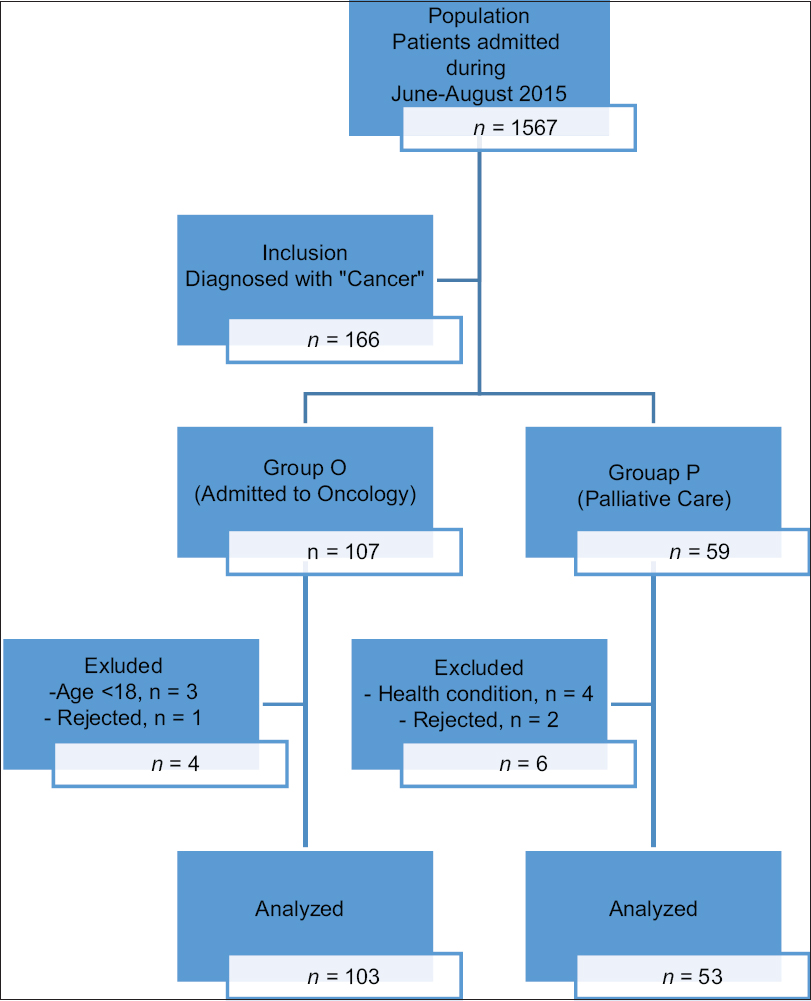

A group of 153 patients (103 from oncology unit, “Group O” and 53 from palliative care unit, “Group P”) who were diagnosed with cancer in the Medical Oncology Hospital at the Ege University School of Medicine were included in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Exclusion criteria were being < 18 years old, difficulty in answering the questionnaires due to language or cognitive limitations, and severe health problems affecting their ability to answer questions [Figure 1].

- Study patient flow diagram.

Sociodemographic and clinical data (age, sex, type of cancer, type and localization of pain, medication, cancer treatments, etc.) about the patients were obtained from medical records and face-to-face interviews. The Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) questionnaire was used for NP assessment. The DN4 consists of 10 questions. Each “yes” answer was scored as 1 point and each “no” answer as 0 points. A total score of 4 points or above were considered to have NP.[14] The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) were used to determine the characteristics of pain and its effect on the quality of life. ESAS consists of 10 questions, which evaluates patient's symptoms (pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, well-being, shortness of breath, etc.) and each question is scored from 0 to 10 points.[15] HADS is a test consisting of 14 multiple-choice questions evaluating anxiety and depression. Higher scores indicate higher anxiety and depression.[16] The BFI consists of 9 questions to assess fatigue and each item is scored from 0 to 10 points. A total score of 1–3 points indicates mild, 4–6 points indicates moderate, and 7–10 points indicates severe fatigue.[17] The BPI consists of 9 main questions designed to evaluate the presence, localization, and severity of pain, and its effect on quality of life; higher scores indicate increased pain and deterioration of functioning.[18]

Statistical analysis

The Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS v2007) and the Power Analysis and Sample Size (PASS v2008) (Utah, USA) programs were used for statistical analyses. The descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, median, frequency, and ratio) were used to analyze the data along with Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test for two group comparisons involving the quantitative data with and without normal distribution, respectively. Pearson's Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, Fisher–Freeman–Halton test, and Yates Continuity Correction Test (Chi-square test with Yates correction) were used for the comparison of qualitative data. Significance was accepted at P < 0.01 or P < 0.05, where appropriate.

RESULTS

A total of 156 cancer patients were included in the study: 53 in the palliative care unit (Group P) and 103 in the oncology unit (Group O). NA and NS were observed in 39.7% (n = 62) and 32.7% (n = 51) of all participants, respectively. When cancer patients without pain were excluded, these numbers were 54.9% and 45.1%, respectively. Patients with NA in Group P and Group O were 48.4% and 51.6%, respectively.

The most common type of cancer found in the study was cancer of the gastrointestinal system (GIS, 31%) followed by breast cancer (22.1%). The most common localization of pain was in the lower extremity (41.6%). The descriptive data for study participants in each group were summarized in Table 1.

There were no significant relationships among the groups (Group O vs. Group P, NA vs. NS), intergroup (Group O NA/NS vs. Group P NA/NS) and intragroup (NA vs. NS) comparisons in terms of chemotherapy (CT), radiotherapy (RT), or surgery features (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

Most frequently used medications for pain management were opioids (29.2% in Group O, 24.8% in Group P, total %54) followed by paracetamol (12.4% in Group O, 15% in Group P, total 27.4%), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (8% in Group O, 3.5% in Group P, total 11.5%), antiepileptics (5.3% in Group O, 2.7% in Group P, total 8%), and steroids (0.9% in Group O, 5.3% in Group P, total 6.2%). No significant relationship was found between the groups (Group O vs. Group P, NA vs. NS), intergroup (Group O NA/NS vs. Group P NA/NS), and intragroup (NA vs. NS) in terms of medication use except for steroid use, which was significantly lower in Group O than Group P (P < 0.05) [Table 3].

Tables 4 and 5 show general (Group O vs. Group P, NA vs. NS), intergroup (Group O NA/NS vs. Group P NA/NS), and intragroup (NA vs. NS) comparisons of scores from the BFI, ESAS, HADS, and the BPI. Among the entire group of participants, the BPI impact and severity, and ESAS total, pain, fatigue, nausea, appetite, and well-being scores of patients with NA were significantly higher than those with NS (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05); there were no significant differences in other scale parameters (P > 0.05). The BPI severity, the BFI, HADS, depression and anxiety, and ESAS total, fatigue, nausea, and appetite scores of patients in Group O were significantly lower than those in Group P (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05); there were no significant differences in other scale parameters (P > 0.05). In Group O, the BPI severity and impact, and ESAS total, pain, nausea, and appetite scores of patients with NA were significantly higher than those with NS (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05); there were no significant differences in other scale parameters (P > 0.05). In Group P, the ESAS pain score of patients with NA was significantly higher than those with NS (P < 0.05); there were no significant differences in other scale parameters (P > 0.05). Among patients with NA, the BFI, HADS depression, and ESAS total and fatigue scores of patients in Group O were significantly lower than those in Group P (P < 0.05); there were no significant differences in other scale parameters (P > 0.05). Among patients with NS, HADS anxiety and ESAS nausea scores of patients in Group O were significantly lower than those in Group P (P < 0.05); there were no significant differences in other scale parameters (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The overall incidence of neuropathic pain (NA) in cancer patients was 39.7% (54.9% among patients with pain) in this study. It was found that physical and psychological symptoms were observed more commonly among patients with NA compared with patients having nociceptive pain (NS) and that this impact was more evident in patients in the palliative unit (Group P) compared with the patients in the oncology unit (Group O). It was found that the pain was localized most commonly in the lower extremity (41.6%) and that GIS cancers were the most common types of cancer (31%). No significant difference was found in or among the groups in terms of the cancer-related treatments (CT, RT, or surgery) or the type of medications used.

The overall incidence of NA was found between 19% and 39% in previous studies (39.7% in the present study).[4] The incidence of NA in Group P was 48.4% in the present study. Similarly, the incidence of NA was found to be as high as 58% in previous studies evaluating patients in special pain units or palliative care units.[121920]

The most common types of cancer and localizations of pain in cancer patients with NA vary among the previous studies in the literature. Jain et al. has found the most common localization of NA as the thoracic region (36.7%) and the most common type of cancer as head and neck (30%). The authors speculated that this issue related to rich neuronal innervation.[21] In addition to studies reporting the most common type as respiratory cancers and thoracolumbar distributions, other studies identify GIS cancers as the most commonly observed, which is consistent with the present study.[112223] These diverse results may be due to such reasons as the time of the study, differences in the underlying pathophysiology, indications for hospitalization, and differences in protocols and treatments from clinic to clinic or from country to country.

NP in cancer patients may be directly related to cancer or may also occur due to treatment modalities (surgery, RT, or CT). In previous studies, the incidence of CT in the etiology of NA was found between 30% and 70%, RT between 25% and 47%, and surgery between 60% and 90%.[24252627] In a comparative study, Rayment et al. have found that the ratio of RT was higher in patients with NA (45.1%) and the ratio of CT was higher in patients with NS (40.6%).[11] Although we found a higher percentage of CT (79%) and surgery (66.1%) history among the patients with NA, interestingly, we found no relationship to the type of pain. Considering the fact that certain chemotherapies may cause NA, the differences among studies may be due to such reasons as the type of CT, duration of treatment, and surgical complications.

Opioids are currently the most preferred treatment option in cancer patients.[28] However, adjuvant analgesics are frequently included in the treatment due to unsatisfactory response to the treatment.[29] Previous studies have reported opioid use in cancer patients as 85%–88% and adjuvant analgesic use as 43%–50%[212223] and noted that the rates are higher in hospitalized patients.[3031] Although nonopioid drugs such as NSAIDs and paracetamol have quite limited efficacy against neuropathic cancer pain, they are prescribed frequently and alleviate symptoms in some cases since pure NA is not observed in general.[8243233] In the present study, the rate of opioid and adjuvant analgesic use in patients with NA was 54% and 8%, respectively. Although there was no difference between or within the groups in terms of medication use in the present study, it was found that the patients included in the study did not receive adequate analgesic treatment even though they were hospitalized. It is striking that only 9.7% of patients with NA complaints were receiving antiepileptic drug treatment although they are the first choice in almost all treatment guidelines for NA.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous studies comparing the cancer patients in palliative and oncology units in terms of the effects of NS and NA on the quality of life. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that NA causes depression, anxiety, and sleep problems in cancer patients, affecting the daily lives of both the patient and their family, and reducing their quality of life.[1293435363738] In a European study on 1051 cancer patients, NS was shown to affect the physical, social, and cognitive aspects of patients’ quality of life significantly more than NA.[11] In a study by Mehmem et al., on 175 cancer patients referred to palliative care, the patients with NA were found to have higher mean total ESAS scores (63) than those with NS (41).[23] Similarly, it was found in the present study that NA affects the patients’ physical and psychological symptoms more greatly than NS and that this impact (pain severity, fatigue, depression, and ESAS symptom scores) was higher among the patients in the palliative unit compared with those in the oncology unit.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the present study. First, we included only hospitalized patients in the study. Second, the number of patients was relatively low in the groups, and there was a substantial difference in the number of patients in the groups (fewer patients in the palliative group). Only the DN4 was used to assess the presence of NP, and hence, mixed pain was not assessed separately. Exclusion of terminal phase cancer patients who have a worse prognosis with inadequate cognitive functions may be another limitation.

CONCLUSION

NP is still a serious problem affecting everyday life in cancer patients because of the heterogeneity of the underlying causes and the lack of clear data on its diagnosis and treatment. With the advent of new technologies and therapies, cancer patients have a longer survival, and thus, there is an increase in the incidence of symptoms affecting their quality of life, such as NP. Using combinations of drugs with different mechanisms of action may provide effective treatment. However, inadequate or unsuitable treatments, in particular, can significantly affect the pain-related quality of life in cancer patients, while adversely affecting the quality of life due to drug side effects and interactions.

Since there was a homogeneous distribution among the groups in terms of both cancer treatment and pain management, we directly related the deterioration of the patients’ quality of life to NP. For this reason, we think that it is important for patients to get an appropriate and effective treatment for NP. There is a need for additional well-planned studies in the future to assess both the diagnosis and the treatment responses.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Management of cancer pain: Basic principles and neuropathic cancer pain. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1078-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of pain, fatigue, sleep and quality of life (QoL) in elderly hospitalized cancer patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:e57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and aetiology of neuropathic pain in cancer patients: A systematic review. Pain. 2012;153:359-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. J Pain. 2006;7:281-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health and quality of life associated with chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin in the community. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:143-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136:380-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms and management of neuropathic pain in cancer. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:107-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1985-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuropathic cancer pain: Prevalence, severity, analgesics and impact from the European palliative care research collaborative-computerised symptom assessment study. Palliat Med. 2013;27:714-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of pain quality descriptors in cancer patients with nociceptive and neuropathic pain. In Vivo. 2007;21:93-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30, version 3.0) in terminally ill cancer patients under palliative care: Validity and reliability in a Hellenic sample. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:135-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4) Pain. 2005;114:29-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: Use of the brief fatigue inventory. Cancer. 1999;85:1186-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- The brief pain inventory: Revealing the effect of cancer pain. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1020.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tools for identifying cancer pain of predominantly neuropathic origin and opioid responsiveness in cancer patients. J Pain. 2009;10:594-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, etiology, and management of neuropathic pain in an Indian cancer hospital. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2009;23:114-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- First evidence of oncologic neuropathic pain prevalence after screening 8615 cancer patients. Results of the on study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:924-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain characteristics and treatment outcome for advanced cancer patients during the first week of specialized palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:104-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advances in the therapy of cancer pain: from novel experimental models to evidence-based treatments. Signa Vitae. 2007;2(Suppl 1):S23-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain and neuropathy in cancer survivors. Surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy can cause pain; research could improve its detection and treatment. Am J Nurs. 2006;106:39-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer pain and its impact on diagnosis, survival and quality of life. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:797-809.

- [Google Scholar]

- Radiation-induced brachial plexus neuropathy in breast cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 1990;29:885-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strategies for the treatment of cancer pain in the new millennium. Drugs. 2001;61:955-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breakthrough pain in the management of chronic persistent pain syndromes. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:S116-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptoms during cancer pain treatment following WHO-guidelines: A longitudinal follow-up study of symptom prevalence, severity and etiology. Pain. 2001;93:247-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain treatment and outcomes for patients with advanced cancer who receive follow-up care at home. Cancer. 1999;85:1849-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of pain relief with drug side effects in postherpetic neuralgia: A single-dose study of clonidine, codeine, ibuprofen, and placebo. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;43:363-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- NSAIDS or paracetamol, alone or combined with opioids, for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;1:CD005180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer-related pain: A pan-european survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1420-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mood states of oncology outpatients: Does pain make a difference? J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:120-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study to determine the association between physical symptoms and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2004;18:558-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Taking action to ease suffering: Advancing cancer pain control as a health care priority. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:285-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of pain and health-related quality of life between two groups of cancer patients with differing average levels of pain. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:726-35.

- [Google Scholar]