Translate this page into:

Responding to Palliative Care Training Needs in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Era: The Context and Process of Developing and Disseminating Training Resources and Guidance for Low- and Middle-Income Countries from Kerala, South India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Chitra Venkateswaran, Department of Psychiatry and Palliative Care, Believers Church Medical College Hospital, Tiruvalla, Kerala, India. Mehac Foundation, Kochi, Kerala, India. E-mail: chitven@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Palliative care has an important role to play in the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. It is integrated and is a key component in the governmental and community structures and services in Kerala, in India. Palliative care in the state has grown to be a viable model recognized in global palliative care and public health scene. The community network of palliative care, especially the volunteers linking with clinical teams, is a strong force for advocacy, relief support including provision of emergency medications, and clinical care.

Objective:

To develop a palliative care resource tool kit for holistic care of patients affected with COVID-19 and to support the health-care workers looking after them to enable palliative care integration with COVID-I9 management.

Methods:

The Kerala State government included senior palliative care advisors in the COVID-19 task force and 22 palliative care professionals formed a virtual task force named Palli COVID Kerala as an immediate response to develop recommendations. Results: Developed a palliative care in COVID-19 resource toolkit which includes an e-book with palliative care recommendations, online training opportunities, short webinars and voice over power point presentations.

Conclusion:

Integrated Palliative care should be an essential part of any response to a humanitarian crisis. The e resource tool kit can be adapted for use in other low- and middle-income countries.

Keywords

Community participation

coronavirus disease 2019

guidelines

health system

India

Kerala

low- and middle-income countries

palliative care

triage

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic,[1] caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), has affected populations and economies across the world. By the end of April 2020 there were more than three million reported infections in 215 countries leaving a death toll of two hundred thousand.[2] Our knowledge of the disease and demographics are still evolving as are treatment interventions and outcomes. Increasingly clear is the huge, unexpected burden of health-related suffering affecting the general population in isolation and lockdown situations, those with acute and chronic health-care needs as well as those becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2. This has been described as a “tsunami of suffering”[3] and is changing the face of illness, death and dying in our societies. Despite this, palliative care is often not prioritised in initial government responses.[4] We also know that mortality for those with COVID-19 increases with age[56] and that presence of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, hypertension, cancer, and chronic kidney disease[78] significantly increase palliative care needs. Health systems, whatever the starting levels of resources, become strained and systems of testing and triage are still being developed. Many who are COVID-19 positive are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms but a significant number will have a more severe illness trajectory and get referred to hospital for further management.[7] The outcomes for those triaged to invasive ventilation is poor.[9] Moreover, there is significant concern about sufficient access to such interventions, the importance of recognising those who may not benefit[10] and the need for holistic care for both groups. According to the state disaster management authority, Kerala has 1398 intensive care unit (ICU) beds and 832 ventilators in the government hospitals and approximately 6664 ICU beds and 1470 ventilators in the private sector. Efficient triaging and distribution of this scarce resource is a moral and ethical challenge. Recent state legislative changes based on the supreme court judgment of 2018 on legalization of advance medical directives have yet to have clarity at the state level implementation for withholding and withdrawing treatment though new guidelines are being developed to support end of life care decision-making.[1112] To aid physicians in decision-making, the Indian Council of medical research has also published consensus guidelines on do not attempt resuscitation.[13] Effective triage based on the needs of the individual and the available resources is essential and challenging.[14] Integrated palliative care is essential at each stage of this process and yet we know many health-care workers have not been trained in core palliative care competencies. The essential medications for symptom control including opioids are often not accessible[15] and this represents a significant barrier. In humanitarian emergencies the goal is not only to save lives but also to address suffering and there is an increasing recognition of the importance of integrating palliative care yet few models are available.[16171819]

India, the seventh largest country in the world, with a population of 1.3 billion, had its first positive CoV reported from the State of Kerala on January 30th.[20] Since then the number of cases has been on the rise and as of May 4, 2020, there are more than 40,000 cases all over the country in 32 states and union territories with more than 1300 deaths.[21] In this context, the core concerns of holistic palliative care are imperative,[22] including effective communication and goals of care decision-making, prompt symptom management and psychosocial support for patients, caregivers, and health-care staff. Palliative care experts can also provide valuable input to policy and national task forces as they seek to address this pandemic and provide training for frontline workers in core palliative care competencies.[323] We describe how Kerala was both vulnerable but also prepared for COVID-19 and how state strategies are being enacted. We also describe the innovative palliative care collaboration as part of integration within Kerala State COVID-19 task force to develop training resources and deliver education aimed at supporting generalist palliative care interventions by frontline health-care workers across Kerala and to other low- and middle-income settings.

Background to Kerala; vulnerability and preparedness

Kerala's 30 million population is increasingly aging with many elderly relatives at home while their families work outside Kerala and travel significantly between Kerala and the Middle East region. More than 2.5 million interstate and migrant workers travel into Kerala from other parts of India and Nepal and are known as “Adithi thozhilali” (guest workers). There is also significant social and medical tourism to this beautiful part of India. The social and political environment in Kerala includes a longstanding priority on equity, inclusiveness and a secular approach to government. Kerala's achievements in social and health indicators such as education, life expectancy, maternal mortality and infant mortality rates are far higher than the India average.[24] There are many examples of successful social experiments which involve the community, such as the Kudumbasree movement[25] engaged in empowering women, and the Peoples Plan Campaign in 1996,[26] which focused on decentralizing bureaucracy and enabling the implementation of projects with delegation to local governing bodies at the village level called Panchayats. Primary care is a major responsibility of these Panchayats, along with the primary health center (PHC), the peripheral unit of the Department of Health. The secondary care level of health care in each district is the Taluk Hospital. This network allows government services to work with the community, maintaining values of accountability, responsiveness to need and demands with a component of feedback locally. This system has become more robust, encompassing preventive and promotive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative care. Kerala also was the first state where the licensing process of strong opioids was modified to improve availability. The state formulated a palliative care policy in 2008, which integrated palliative care into primary and secondary health care and made it a key component in the governmental and community structures and services. This built upon innovative community empowerment and civil society mobilisation over the previous 20 years. Now every one of the state's PHCs which number more than 900 has a trained full-time palliative care nurse who makes at least one home visit to every bed-bound patient at least once a month.

In 2018, Kerala experienced two significant events, which facilitated social readiness for the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. The zoonotic Nipah virus struck Kerala affecting 19 people with 17 deaths in 4 weeks. This presented the health system with the challenge of managing a newly emerged infectious disease. A rapid, coordinated outbreak response which included timely diagnosis, real-time data sharing, sample transport and contact tracing led to the successful containment of the outbreak.[27] Following this the government put measures and protocols in place to ensure better preparedness in the event of a similar crisis in the future. The second and devastating event was the extensive flooding in which 400 people lost their lives and around 800,000 people were displaced. Immediate steps were taken by local and district administration to reduce the impact of the disaster. Existing networks were effectively mobilized and new networks established within government departments and community services led by the department of health. Community individuals and agencies played a significant and immediate role with nongovernmental organizations, faith centers, educational institutions and volunteers contributing to the relief work. The effective use of social media and volunteer workforce in giving alerts, identifying vulnerable communities and supporting search and rescue made the flood relief activities in Kerala unique.[28] The community networks of palliative care, especially the volunteers linking with clinical teams, turned out to be a strong force for advocacy, relief support including provision of emergency medications, and clinical care. Palliative care teams offered psychosocial support to 83,028 survivors in 1 week in the aftermath of these unprecedented floods.[29]

Kerala learned from these two major crises that transparency and collaboration are critical and must be prioritized during a public health emergency. It also tested and demonstrated effective communication and direct engagement with the community.

The current COVID-19 pandemic is again a novel zoonotic infection and the state level response is detailed below.

Integration of palliative care within coronavirus disease 2019 management

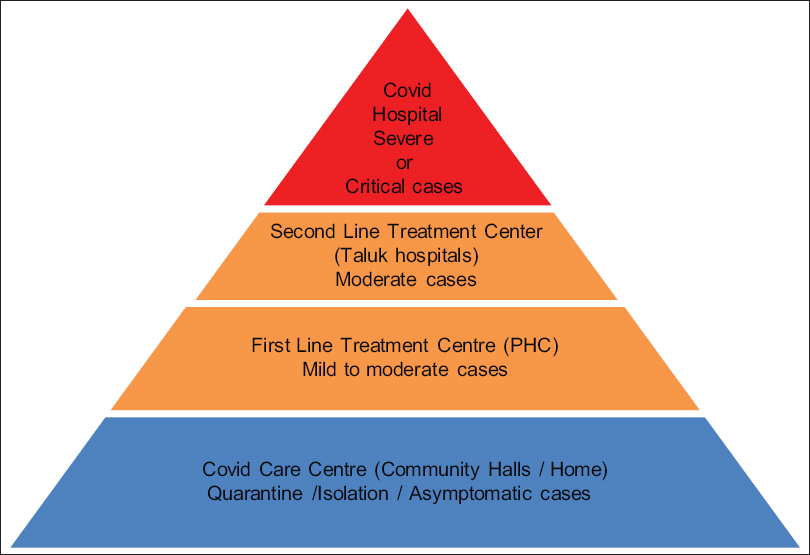

The Kerala government has put forward an ambitious plan with three main objectives of least morbidity, no mortality and no community spread. From the first confirmed COVID-19 case they implemented rigorous checking at international airports with contact tracing and quarantine measures supported by social support in dedicated centers. The primary level health centers are being converted to COVID-19 first line treatment centers [Figure 1] to look after patients who are COVID-19 positive with mild symptoms and referral on for further management in district and referral hospitals for the more critically ill.[30] There is a dedicated telehealth helpline in every panchayat under the PHCs including video calls with doctors as well as facilitating home delivery of medications. Community teams are involved in providing psychological support to quarantined people as well as monitoring the elderly under their care, with regular telephone calls enquiring about symptoms of disease, [Figure 2] advising on social distancing and advocating for hand hygiene.

- Pyramid of clinical care for coronavirus disease 2019 treatment planned by Kerala State Government

- Support Systems and treatment facilities at panchayat level. ASHA: Accredited Social Health Activist

PALLIATIVE CARE TRAINING INTERVENTION;METHODS

The Kerala State government included senior palliative care advisors in the COVID-19 Task Force. As a civil society response, 22 palliative care professionals got together to form Palli COVID Kerala in the last week of March 2020 with members working across health systems within the state, across India, and internationally. It highlighted the vital areas of triage including goals of care, ethics and communication; symptom control including access to essential medicines, management of distress including psychosocial and spiritual support, end of life care and health-care worker support. In response to the lack of capacity of the existing health-care system to deliver these key palliative care interventions among frontline staff, the group brought a wide range of competencies including palliative medicine, internal medicine, anesthesiology, critical care, pediatrics, and psychiatry as well as experience in the implementation of projects during complex humanitarian emergencies. The goal was to develop training resources in the form of guidance algorithms in an e-book for frontline health-care workers of relevance to low- and middle-income settings. A short timescale of 2-weeks was agreed followed by the development of a faculty pool that would deliver online training with periodic revisions of the e-book. Key priorities were agreed at the first virtual meeting involving all the members, from which a working group was selected. The working group met every day for an hour via video conferencing. The guidelines were drafted based on available evidence, robust discussion, brain storming, adaptation to local milieu and mutual consensus. Information was shared using WhatsApp for comments and critique from the larger group. The guidelines were drafted primarily considering the local context but options were included to enable adaptation to other settings, particularly low- and middle-income countries. Following eleven 1-h videoconferences of the working group, an e-resource book was completed to support palliative care interventions in the COVID-19 setting, which has been submitted to the Government of Kerala.[31]

PALLIATIVE CARE TRAINING INTERVENTION;RESULTS

We have developed and started dissemination of a comprehensive Palliative Care in COVID-19 Resource Toolkit [Figure 3]. This includes an e-book[31] which covers the key areas for direct palliative care roles in COVID-19 using a series of management algorithms but also signposts and expands to general palliative care needs and settings. [Figure 4] shows domains covered by Ebook.

- Palliative care in COVID-19 resource toolkit

- Domains covered by the E-book

Triage including decision-making and ethical framework algorithm [Figure 5]

- Decision-making and Ethical Framework Algorithm *World Health Organization Performance status ** Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome ***should be incorporated at all stages

We describe the strategy and process being rolled out by the government of Kerala which can be contextualized for different settings. Using the levels of framework described in Figure 1 the process of triage assess the clinical condition informs the interventions needed and determines the appropriate referral and place of care At each stage of triage, communication, and goals of care discussion are essential alongside holistic care. These crucial goals of care discussions must be supported by clear ethical frameworks with assessment based on co-morbidities, age and pre-COVID-19 functional status as well as clinical findings. For ease of use in generalist settings we recommended the WHO performance status scale at community and district levels. The aim of triage is to achieve clinical consensus about treatment pathways, communicate with the patient and family, document with triage supervision support and then facilitate appropriate referral processes while ensuring symptom control and holistic care. Our goal is to individualize decision-making on clinical grounds with patient and family involvement while taking into account the available resources. This triage is sensitive and should not delay referral to intensive care for those likely to benefit. It should encourage open conversations and consensus for those unlikely to benefit while ensuring high quality of care.[10] Patients and families who are triaged for conservative management should be cared for in clinical areas where refractory symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual support as well as end of life care can be optimized. Goals of care discussion will be an ongoing process and will be supported by advance care planning. Palliative care teams will be instrumental in enabling triage particularly with patients and families who have prior co-morbidities where anticipatory care discussions are so important.

Symptom control including access to essential medicines

Essential medicines should be accessible and affordable for all palliative care needs but particularly for the main symptom challenges.[32] This is particularly acute for opioids which are already unavailable in many settings.[33] Protocols should be available and training completed alongside expert back up by phone or in person. The most common symptom cluster is breathlessness and agitation[34] and this will need prompt and careful attention. Titration of medications against symptoms needs to include the severe refractory symptoms seen in those who may deteriorate fast and may not be triaged to an intensive care setting. As in any setting, careful assessment, appropriate investigations, correcting the correctable and nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions are needed. Breathlessness is often accompanied by agitation where a combination of opioids and benzodiazepines will be the mainstay; but delirium due to other causes must be considered where anti-psychotics have a role. Algorithms were developed for the management of breathlessness [Figure 6] and management of agitation with and without disorientation [Figure 7]. Other symptoms such as cough and secretions and advice on routes of medication and care in different settings are included.

- Algorithm for management of breathlessness

- Algorithm for management of delirium and agitation

Management of distress including psychological, social and spiritual support and the accompanying areas of grief, bereavement and loss are perhaps some of the most essential. Assessment is encouraged using a distress visual analogue scale embedded in the Making sense of distress Algorithm [Figure 8] with advice for offering psycho-education, effective communication, pharmacological interventions and red flags to initiate referral. Tips for “dos and don't's” are included as well as examples of empathetic responses and problem solving approaches. Adequate information to address stigma is particularly important. Staff on health phone lines or trained volunteers may well be able to engage in effective psychosocial interventions using protocols. Social and practical help is very important and needs to be coordinated alongside government planning systems. Mobilizing and empowering community groups and faith-based organizations is also crucial not only for the current pandemic control but also to look for, identify and support at-risk populations with significant vulnerability.

- Making sense of distress algorithm

End of life care

The end of life care algorithm outlines the symptom control, nursing care and holistic issues at this crucial time. This is a time where communication is vital to act as a bridge between patient and families to alleviate the distress of isolation. The innovative use of technology is recommended such as recorded messages, music or prayers, or facilitated live virtual conversations. The opportunity to say goodbye is particularly important and the reassurance that a loved one is not alone or abandoned. For families who cannot be present, conveying a message about the care received is an important part of bereavement care. When frontline staff are under significant pressure we suggest a team approach where initial conversations be followed up by dedicated psychosocial and spiritual care workers.

Supporting compassionate care and addressing burnout for health-care workers Algorithm is essential. Working in stressful environments, dealing with stigma and anger, lack of protective equipment for oneself and others, balancing scarce resources, personal needs and being seen as superheroes who do not need rest or protection are all challenges for health-care workers. Some cope by blocking out or emotional distancing and many feel a sense of compassion-fatigue or even moral distress if support is not given. Yet precisely the need for compassionate care and mutual humanity demands that we must take care of our health-care workers and ourselves as we also care for patients and families in need.

Having developed this e-resource for palliative care in COVID-19, we then initiated training for frontline staff in community, primary, secondary and tertiary health care in Kerala as well as in other low- and middle-income settings. With our faculty pool in place we commenced online training using the Project extension for community health-care outcomes (ECHO) platform which is already involved in palliative care education in the country.[35] Feedback from faculty, participants and the Government of Kerala as well as WHO SEARO office led to an update of the e-resource book, addition of an executive summary and the development of 9 standard 30-min webinars. Voice over PowerPoint presentations with full notes have been prepared for low bandwidth settings. These combined resources can be used for face to face or flipped classrooms delivery appropriate to local context with the addition of relevant information and case discussions.

Impact and way forward

The complete Palliative Care in COVID-19 Resource Toolkit for low-and middle-income country (LMIC) was submitted to the State government, uploaded to Pallium India website and widely shared on national and International palliative care forum as a COVID-19 resource. The Expert Committee on COVID-19 management appointed by Government of Kerala has recognised it formally and directed the Additional District Medical Officers of all Districts and National Health Mission coordinators to use the Palliative Care in COVID-19 Resource Toolkit as the background training material for palliative care training programs. The Palli COVID Kerala faculty pool will be a resource for this as well as continuing the ECHO training sessions with Pallium India which have now had more than one hundred participants from many other states in India and LMIC countries. In total more than 11 countries has utilised the resources either for training or to support their own advocacy. The WHO SEARO office has acknowledged the Palliative Care in COVID-19 Resource Toolkit and agreed to disseminate.

CONCLUSION

This COVID-19 pandemic underlines the crucial need for holistic care and emphasizes the core palliative care competencies of communication, triage and decision-making, symptom control, managing distress, end of life care and health worker support alongside community empowerment. Palliative care has to be integrated at all levels and should be an essential part of any response to a humanitarian crisis and going forward must be included in training programmes at preservice and in-service curriculums. Essential medicines should be routinely available and in particular the issues of access to opioids must be urgently addressed in a safe and effective manner. This pandemic has emphasized the need to manage scarce health resources efficiently, flexibly but also with ethically transparent and efficient manner while ensuring that clinical decisions are individualized. Innovation and creativity to find local solutions is expanding. However, health-care staff faced with compassion fatigue need to be shown the same compassion and humanity we seek to offer patients and families. Vulnerable populations especially those struggling with the mental and social effects of lockdown need to be seen and supported. Communities are crucial environments for addressing stigma so we must continue to mobilize and empower and hear the voices of those affected by COVID-19. Our core values are being challenged but also revealed through the many acts of solidarity and compassion. We hope this Palliative Care in COVID-19 Resource Toolkit from Palli COVID Kerala and Pallium India will make a significant contribution to health-care worker competency, capacity, and resilience. These resources will be updated on a regular basis as the pandemic is a rapidly changing scenario. We seek to ensure widespread dissemination and awareness with the ultimate aim of improving the quality of life, relieving suffering and maintaining dignity for patients and families with palliative care needs in this time of pandemic and beyond.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 2020. WHO Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

- 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak Situation. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- The key role of palliative care in response to the COVID-19 tsunami of suffering. Lancet. 2020;395:1467-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Redefining palliative care – A new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020 pii: S0885-3924(20)30247-5

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: A model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:669-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Severe Outcomes Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – United States, February 12 – March 16 2020

- The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 2020 pii: e206775

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. The BMJ Opinion the Arrival of Covid-19 in Low and Middle-Income Countries Should Promote Training in Palliative Care. Available from: https://blogsbmjcom/bmj/2020/04/28/the-arrival-of-covid-19-in-low-and-middle-income-countries-should-promote-training-in-palliative-care/utm_campaign=shareaholic&utm_medium=facebook&utm_source=socialnetwork&fbclid=IwAR3Yv19-OheAwSXYb804s4vMFXka8IcC6j6kpLNzSj50gNLVpZUjoclasnw

- After the Supreme Court judgment on autonomy: What the oncologist needs to know. Indian J Cancer. 2018;55:207-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2019. IAPC Newsletter; Blue Maple. Indian Association of Palliative Care. Available from: https://www.palliativecare.in/iapc-newsletterapril-2019/

- ICMR Consensus Guidelines on do not attempt resuscitation. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:303-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facing covid-19 in Italy – Ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic's front line. New Engl J Med. 2020;82:1873-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The lancet commission on palliative care and pain relief – Findings, recommendations, and future directions. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6:S5-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief into Responses to Humanitarian Emergencies and Crises: A World Health Organization Guide 2018

- Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response. Switzerland: Practical Action; 2018.

- Palliative care in humanitarian crises: A review of the literature. J Int Humanitarian Action. 2018;3:5.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 pandemic-call for national preparedness. J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68:11.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in

- Symptom management and supportive care of serious COVID-19 patients and their families in India. Indian J Crit Care Med 2020

- [Google Scholar]

- “Palliative care and the COVID-19 pandemic.”. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395:1168.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Development Experience: Reflections on Sustainability and Replicability. Kerala: Zed Books; 2000.

- Between 'empowerment' and 'liberation' the kudumbashree initiative in Kerala. Indian J Gen Stud. 2007;14:33-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Building local democracy: Evaluating the impact of decentralization in Kerala, India. World Dev. 2007;35:626-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Towards global health security: Response to the May 2018 Nipah virus outbreak linked to Pteropus bats in Kerala, India. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e001086.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flood relief interventions in Kerala: A factsheet and critical analysis based on experiences and observations. Int J Health Allied Sci. 2019;8:290.

- [Google Scholar]

- Providing psychosocial support in Kerala after the floods. Lancet. 2018;392:1181-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Reference Guide for Converting Hospitals into Dedicated COVID Hospitals. Available from: https://dhskeralagovin

- E-Book on Palliative Care Guidelines for COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. India. https://palliumindia.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/e-book-Palliative-Care-Guidelines-for- COVID19-ver1.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care list of essential medicines for palliative care. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21:29-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Access to pain relief and essential opioids in the WHO South-East Asia Region: Challenges in implementing drug reforms. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2018;7:67-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for Symptom Control of Patients with COVID-19 Palliative Care in the COVID-19. Pandemic Briefing Note 2020

- [Google Scholar]

- Can e-learning help you to connect compassionately? Commentary on a palliative care e-learning resource for India. Ecancermedicalscience. 2017;11:ed72.

- [Google Scholar]