Translate this page into:

Response to COVID-19 Crisis with Facilitated Community Partnership among a Vulnerable Population in Kerala, India – A Short Report

*Corresponding author: Anu Savio Thelly, Department of Palliative Medicine, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute, Puducherry, India. anu.savio@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sumitha TS, Thelly AS, Medona B, Lijimol AS, Rose MJ, Rajagopal MR. Response to COVID-19 crisis with facilitated community partnership among a vulnerable population in Kerala, India – A short report. Indian J Palliat Care 2022;28:115-9.

Abstract

The unexpected lockdown announced by the Government of India in March 2020 in response to the pandemic left the coastal community in Kerala deprived of not only essential amenities but also healthcare. Some poverty-ridden, over-crowded coastal regions had been declared as critical containment zones with severe restriction of movement, adding to their vulnerability. People with serious health-related suffering (SHS) in this community required urgent relief. A group of educated youth in the community joined hands with a non-governmental organisation specialised in palliative care (PC) services and strived to find the best possible solutions to address the healthcare needs in their community. This paper reports the collaborative activities done during the pandemic in the coastal region and compares the activities with steps proposed by the WHO to develop community-based PC (CBPC). By engaging, empowering, educating, and coordinating a volunteer network and providing the required medical and nursing support, the programme was able to provide needed services to improve the quality of life of 209 patients and their families who would have been left with next-to-no healthcare during the pandemic. We conclude that even in the context of much poverty, delivery of CBPC with the engagement of compassionate people in the community can successfully reduce SHS.

Keywords

Palliative care

COVID-19

Community engagement

Humanitarian crisis

Community-based palliative care

INTRODUCTION

Kerala, a state in South India with a population of 36 million people, has India’s highest literacy rate (94%) and is noted not only for its human development but also for poverty reduction, making it first among the Indian states in the Human Development Index.[1,2]

Kerala has the second-highest population of fisherfolks in India,[3] numbering about 1.05 million in the 222 fishing villages spread across 102 local self-government institutions (LSGIs) spread along the coastline.[4,5] Although fisherfolk is a vital community in Kerala, they remain neglected, marginalised, and largely left out of the broad development activities. Thus, they remain backwards despite the higher socioeconomic progress, the state has made.[5,6] For example, fisherfolk’s literacy level and educational status are much lower than those of the general population in the state.[7,8] A lack of income-generating opportunities, overcrowded living conditions, lack of access to essential services such as potable drinking water, sanitary toilets, and electricity, poor health among men and women, higher infant mortality rates and lack of access to health facilities are all evidence of this marginalisation.[9]

In 2012, the Indian government launched the National Programme for Palliative Care (NPPC). The Indian Parliament amended the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act in 2014 to make opioids more accessible. PC has been a part of the undergraduate medical curriculum from 2019 onwards. Since 2008, Kerala has had a State PC Policy, revised in 2019, integrating PC at the first administrative level, the Grama panchayat (village LSGI). It has had significant success in extending PC coverage to every primary health centre.[10] Yet, the system leaves much to be desired in terms of both quality and coverage of PC.[11] Although Kerala is trying to improve PC services with the revised policy, the unanticipated pandemic threw many challenges. As a result, the entire system found it difficult to cater to the PC needs in the coastal region.

BACKGROUND

In mid-February 2020, the number of first wave COVID-19 cases gradually increased in the state. The Kerala government took numerous steps to strengthen emergency preparedness, diagnostics, and categorisation of risk involved in reducing the transmission of the COVID-19. In mid-March 2020, the state implemented additional preventive measures with the recurrence of cases, including the immediate shutdown of non-medical educational institutes.[12] In July 2020, contact and local transmission started to surge in the state, with more community spread, first reported in coastal regions such as Poonthura and Pulluvila in Thiruvananthapuram, the capital of Kerala. The state government took stringent efforts to limit disease spread, including labelling these regions as ‘critical containment zones,’ restricting people from entering and exiting these areas, restricting movement across street borders, and imposing controls in fish markets.[13]

The spread of COVID-19 was a significant setback for the resource-dependent coastal communities in Trivandrum because June, July, and August are the most crucial months for indigenous fisherfolk.[14] COVID-19-related restrictions put a stop to the fishing activities and trade, affecting almost all in the coastal region. Moreover, the densely populated fisherfolks’ colonies, with their crowded living environments and inherent occupational hazards associated with their occupation, made these regions vulnerable to intense disease transmission.[13,15]

Locally evolved strategies to meet the PC needs in the coastal region

Community-based PC (CBPC) services were provided at the local community health centre level with community participation. Non-hospital, non-hospice PC was provided to the needed patients in their homes. It is generally patient-centred, cost effective, and comprehensive.[16] It endeavours to involve community members in PC needs assessment, planning, implementation, resource mobilisation, day-to-day management, and evaluation of the PC programme.[17]

When Poonthura was declared a critical containment zone by the government, local people were stranded and left unprepared. They faced scarcity of food, medicines, and other essentials. Coastal Students Cultural Forum (CSCF) is a coastal area-based non-governmental organisation predominantly comprising educated youth within the coastal community. They mobilised essential supplies required for the community members who faced tremendous challenges in terms of availability, accessibility, and supply chain disruptions. A well-wisher of CSCF, a public health expert (First author), then connected the CSCF to Pallium India Trust (a non-governmental organisation based in Thiruvananthapuram). On July 25, the two parties met for the 1st time virtually, and on July 27, the first patient was enrolled. In Pallium India, a dedicated team was formed to attend to and handle the requirements of the coastal region alone, as their requirements were more than just PC. A core team with members of CSCF, Pallium India, and volunteers, was formed to coordinate the service delivery in the coastal community. This official collaborative activity continued till 16 December 2020, when the lockdown was called off and routine activities restored. The patients identified with PC needs were registered under Trivandrum Institute of Palliative Sciences, Pallium India. Regular follow-up visits were scheduled by the home care team of Pallium India since then apart from the regular home care visits, home care visits involving psychiatrist and physiotherapist were also arranged in the coastal region based on the needs. It was noticed that despite well-laid policies and strategies, the integration of PC into these communities was incomplete. Pallium India is continuing to support the PC needs of the patients in this region up to this date with the help of CSCF volunteers and core team members. This article also attempts to compare the sequence of these events to the steps suggested by the World Health Organization (WHO) for establishing CBPC services[17] and outlines the activities carried out by Pallium India and CSCF’s partnership effort. The core PC team examined the collaborative services in the coastal community of South Kerala during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The meeting minutes and summary reports from the CSCF-Pallium India meetings and services were reviewed. The core team also gathered information through round table discussions. The steps undertaken and services provided through the CBPC are illustrated below.

COMPARING THE INCEPTION OF CBPC SERVICES AND STRATEGIES IMPLEMENTED IN THE COASTAL REGION WITH THE WHO’S GUIDELINE FOR SETTING UP NEW CBPC SERVICES

This section describes the phases of a quick need-based evolution of a CBPC programme in a coastal hamlet in South Kerala during the lockdown (between July and December 2020) imposed during the first wave of COVID-19. These phases are compared with the step approach for setting up new CBPC services recommended by the WHO.[17]

Step I: Sensitisation sessions and advocacy programmes to build support

The first step was to hold an awareness session/discussion, including the people in the locality who are likely to be interested in helping others. People associated with CSCF willing to spend some time each week to assist such patients and families were sensitised and also registered as volunteers. The sensitisation programme included a brief introduction to PC and the role of volunteers. In addition, CSCF shared with Pallium India team an overview of coastal communities and their health conditions. This baseline information helped Pallium India plan strategies to meet the community’s health needs.

Step II: Train volunteers

The process of translating a PC plan into action requires strong leadership and a participatory approach to identify what needs to be done to bridge the identified gaps. Twenty-three volunteers were trained in identifying patients in need of palliative care and to communicate it with the team through online training using the Zoom platform as face-to-face training was impossible due to lockdown. The CSCF volunteers compiled a list of patients who needed medical assistance from their community and sent it to the core team (CSCF and Pallium leaders) through the WhatsApp platform. In the 1st week, they compiled a list of 27 patients. Then, volunteers used the helpline that Pallium India had created in response to the pandemic to assist the patients in registration and consultation.

Step III: Adding a nursing component to the programme

The ultimate goal of home-based care is to ‘promote, restore and maintain a person’s maximal degree of comfort and function, including care toward a dignified death at the doorstep.’[18] A nurse-led home care service is at the heart of the CBPC programme. The nurse’s skill in giving care and education to the patient and family is fundamental in PC. Pallium India’s clinical staff had limitations in entering the containment zone. Because some patients required nursing services such as urinary catheter change and wound dressing, the Pallium India-CSCF team initially struggled to get it done. It became obvious that from a long-term point of view, securing the services of a nurse within the neighbourhood was the best option. CSCF identified a nurse in the community (third author) to offer nursing care to patients amidst the pandemic. Pallium India gave her training in PC and equipped her with home care kits and personal protection equipment. In addition to providing patient care, she oversaw volunteer operations on the ground, which resulted in identifying more patients in need of assistance and the timely delivery of care and medications at their doorsteps. This led to the actualisation of the CBPC model in the coastal region. After discussing with the clinical team members who do teleconsultation with patients or caregivers, Pallium India’s pharmacy team packed medicines as per patients prescriptions and labelled them in a way that the volunteers, caregivers, and patients could understand. These packets were regularly picked up by the volunteers who delivered them to the community nurse for distribution among the patients. Additional requirements for support, such as food kits and assistive devices, were also catered to.

Step IV: Add the medical component

Due to a scarcity of trained doctors, obtaining the medical component is frequently the most challenging step. The coastal community well utilised Pallium India’s helpline. Trained doctors provided medical support and information to the coastal communities through teleconsultation. Using the same helpline, social workers and counsellors addressed the psychosocial and spiritual concerns of those with long-term and incurable illnesses.

Step V: Consider adding a regular outpatient clinic

When several lockdown restrictions were lifted by November 2020, the clinical team from Pallium India extended their regular home care services to the coastal community. We realised the need for a regular outpatient clinic. As the availability of a trained doctor and nurse is a prerequisite, patients with PC needs were referred to the nearest outpatient PC clinic at Poovar, run by Pallium India. The patients in need of home care are registered with Pallium India, and the home care team is visiting them based on their needs.

Step VI: Establish a system of regular evaluation and review

There should always be active efforts to identify areas for improvement. In January 2021, trained volunteers from CSCF attended meetings organised by one of the local bodies, where they discussed their experience in planning PC initiatives in their region. This helped the stakeholders understand the challenges and reality of PC service delivery at the grassroots levels. Discussions were also initiated to expand services to needy ambulant patients. Unfortunately, both teams could not implement all the activities planned due to the second wave of COVID-19 in February 2021.

Step VII: Continue with steps I and II

Coverage of neighbouring areas by sensitisation and training of volunteers resulted in 209 locked-in patients and their families getting access to PC, medicines, and food till December 2020. During this period, particular attention was given to the most vulnerable population in the community.

SERVICES PROVIDED BY THE CBPC MODEL IN THE COASTAL REGION

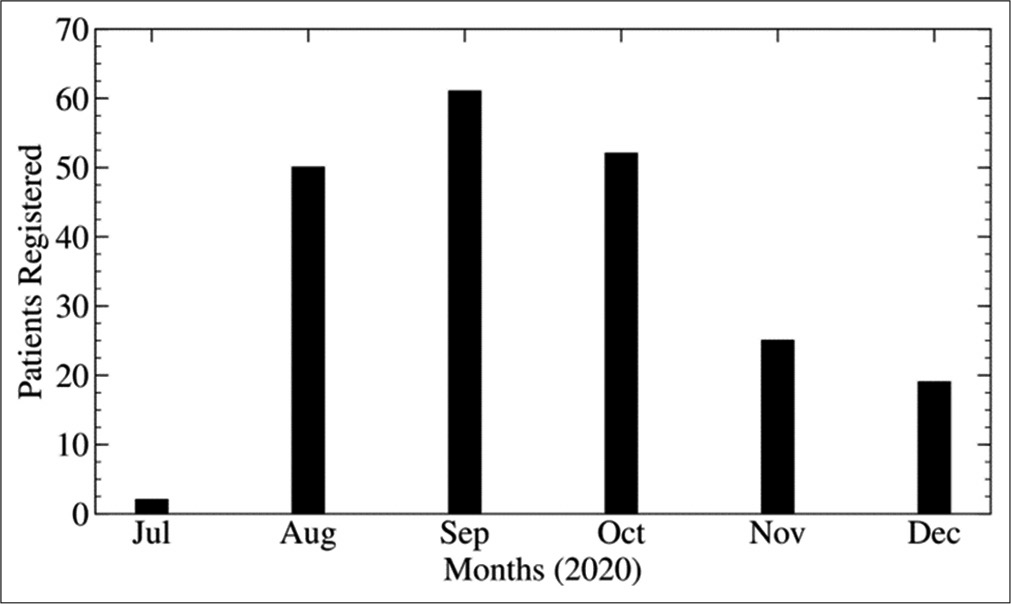

We noticed a peaking in the number of patients registered for PC services during September 2020 and a gradual monthly drop as coverage progressed to saturation of the need, as shown in [Figure 1]. The demographic profile of the patients registered is summarised in [Table 1].

- Patients registered for palliative care services.

| Characteristics | Registered patients, n=209 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | |

| ≤50 | 63 (30.1) |

| 50=70 | 101 (48.3) |

| >70 | 45 (21.5) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 114 (54.5) |

| Male | 95 (45.4) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Cancer | 17 (08.1) |

| Non-cancer | 192 (91.8) |

| Patients with serious health-related suffering | |

| Yes | 99 (47.36) |

| No | 110 (52.63) |

Among the 209 patients, 54.5% were women. The mean age was 57.5 ± 18.1, with an age range from 7 to 95 years. About 91.8% (n = 192) of the patients had non-cancer conditions such as cardiac morbidity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, sequelae of cerebrovascular accidents, and frailty of old age. The remaining patients were diagnosed with different types of cancer. From December 2020 onwards, 47.46% (n = 99) of patients in serious health-related suffering (SHS) from the coastal region started receiving continued PC services from the CBPC approach. These patients were either already registered patients or new patients identified during the telephonic survey or the nurse’s home visit by the Pallium India team. Details of services provided to the coastal community by CBPC services are given in [Table 2].

| Nature of the service provided | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Medicine supply | 209 |

| Psychological support | 108 |

| Food kits | 112 |

| Pressure relieving mattress | 7 |

| Walking aids | 6 |

| Doctor’s home visit | 45 |

| Physiotherapist home care visit | 16 |

| Referrals to link centres | 28 |

| Support for end-of-life care | 4 |

DISCUSSION

All illnesses as such in the context of low health literacy and poverty were amplified during the pandemic by the difficulty in accessing healthcare, regular medicines, and essentials like food. The combined effort of CSCF and Pallium India had met many of their healthcare needs and improved their quality of life, as evidenced by informal feedback given by patients and volunteers. It was noticed that 99 out of 209 patients had continued PC needs that had not been adequately met by the healthcare system even before the lockdown.

The problems of marginalised populations living with life-limiting/threatening and terminal illnesses are often identified late, and they often die without access to PC services.[19] It is seen that SHS was related to the social determinants of health. We could identify several dependent widowed women living alone in this coastal community without appropriate supportive care and resources. This raises doubts about the available provisions for the aged and dying population in marginal communities. The present CBPC approach suggests the need to restructure the existing PC services, with a focus on the ageing and dying population.[11] This calls for an integrated approach with people from different domains under a single umbrella, even the greater number of women among the registered patients for PC points toward the need to conduct a scientific survey to identify patients in actual needs as women mostly stand behind men in accessing adequate healthcare.[20]

Educating, engaging, empowering, and coordinating a PC volunteer network can be an essential strategy for PC delivery. Resources used for training should bring forward and value the experiences of the trainees. Programmes must be designed to respond to local needs and customs, be community based, be linked with local primary healthcare and provide easy access to referral pathways between and across services. In similar humanitarian crises, PC programmes must also be adaptable based on shifting individual and population demands and considering local and national health systems. Thus, a comprehensive CBPC approach covering the continuum of care of patients in SHS, including rehabilitation, psychosocial and spiritual support, should be planned and implemented.

STRENGTH AND WEAKNESS

This case report supports WHO’s guidelines to set up a CBPC service model and demonstrates its relevance during a humanitarian crisis like a pandemic. We had responded to an urgent crisis and so had to proceed without framing the work as implementation research. Our conclusions are based on reports of patients and families rather than on hard data.

CONCLUSION

Our experience taught us that providing PC is much needed in a humanitarian crisis, particularly among vulnerable populations. We also found that compassionate people were eager to help their suffering fellow beings amidst a community with comparatively low literacy and high poverty. If the healthcare system welcomes community members, empowers them with training, and works with them, much of SHS can be alleviated by CBPC approaches. A multidisciplinary PC team needs to support them with healthcare expertise, medicines, and other supplies. The delivery of services by the CBPC model was facilitated by technology, including telephonic helplines and online telehealth services.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- The Kerala model in the time of COVID19: Rethinking state, society and democracy. World Dev. 2021;137:105207.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sub-National HDI-Subnational HDI-Global Data Lab. 2021. Available from: https://www.globaldatalab.org/shdi/shdi/IND/?levels=1%2B4&interpolation=0&extrapolation=0&nearest_real=0&years=2018 [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 18]

- [Google Scholar]

- India-Fishing Families Population by State 2018. 2021. Statista Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/734334/india-fishing-family-population-by-state [Last accessed on 2021 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Coastal Area Development Fisheries Department-Kerala. 2021. Available from: https://www.fisheries.kerala.gov.in/coastal-area-development [Last accessed on 2021 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- The Research Publication. 2021. Available from: https://www.trp.org.in/issues/financial-inclusion-of-marginalised-communities-a-study-on-fisher-households-in-kerala [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 18]

- [Google Scholar]

- The Kerala model: Its central tendency and the outlier. Soc Sci. 1995;23:70-90.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rural livelihood security: Assessment of fishers' social status in India. Agric Econ Res Rev. 2013;26:21-30. Available from: https://www.ideas.repec.org/a/ags/aerrae/158509.html [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 18]

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender Bias in a Marginalised Community: A Study of Fisherfolk in Coastal Kerala. 2021. Available from: https://www.explore.openaire.eu/search/publication?articleId=od_______645:8ba076003620f54558acdcd69bbc1c8c [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 18]

- [Google Scholar]

- The Fisheries Policy. 2006. ADB Independent Evaluation Department. Available from: https://www.adb.org/documents/fisheries-policy [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 18]

- [Google Scholar]

- Local government-led community-based palliative care programmes in Kerala. Rajagiri J Soc Dev. 2016;8:129-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-of-life characteristics of the elderly: An assessment of home-based palliative services in two panchayats of Kerala. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:491.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerala, India's front runner in novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Front Med. 2020;7:355.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Threatens to Engulf Kerala's Coastal Belt. 2020. The Hindu. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/covid-19-threatens-to-engulf-states-coastal-belt/article32053429.ece [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Lockdown in Kerala's Coastal Regions Hits Seafood Shipments to Overseas Markets. 2021. @businessline. Available from: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/lockdown-inkeralas-coastal-regions-hits-seafood-shipments-to-overseas-markets/article32147654.ece [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Situation in Thiruvananthapuram's Coastal Areas Scarier than What the Official Figure Hints. 2021. OnManorama. Available from: https://www.onmanorama.com/news/kerala/2020/07/08/thiruvananthapuram-coastal-regions-covid-19-spread-triple-lockdown.html [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of community-based palliative care services: Perspectives from various stakeholders. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:425-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planning and implementing palliative care services: A guide for programme managers. 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: https://www.apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250584 [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 22]

- [Google Scholar]

- Future of palliative medicine. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:95-104.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Right to Accessible Healthcare: Bringing Palliative Services to Toronto's Homeless and Vulnerably Housed. 2016. UBC Medical Journal. Available from: https://www.ubcmj.med.ubc.ca/right-to-accessible-healthcare-bringing-palliative-services-to-torontos-homeless-and-vulnerably-housed [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 20]

- [Google Scholar]

- The Astana declaration. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ press-releases/new-global-commitment-primary-health-care-all-astanaconference. [Last accessed on 2021 Aug 29].