Translate this page into:

Self-image of the Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Mixed Method Research

Address for correspondence: Dr. Mamatha Shivananda Pai; E-mail: mamatha.spai@manipal.edu

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the study was to assess the self-image of the patients with head and neck cancers (HNCs) by using a mixed method research.

Subjects and Methods:

A mixed method approach and triangulation design was used with the aim of assessing the self-image of the patients with HNCs. Data was gathered by using self-administered self-image scale and structured interview. Nested sampling technique was adopted. Sample size for quantitative approach was 54 and data saturation was achieved with seven subjects for qualitative approach. Institutional Ethical Committee clearance was obtained.

Results:

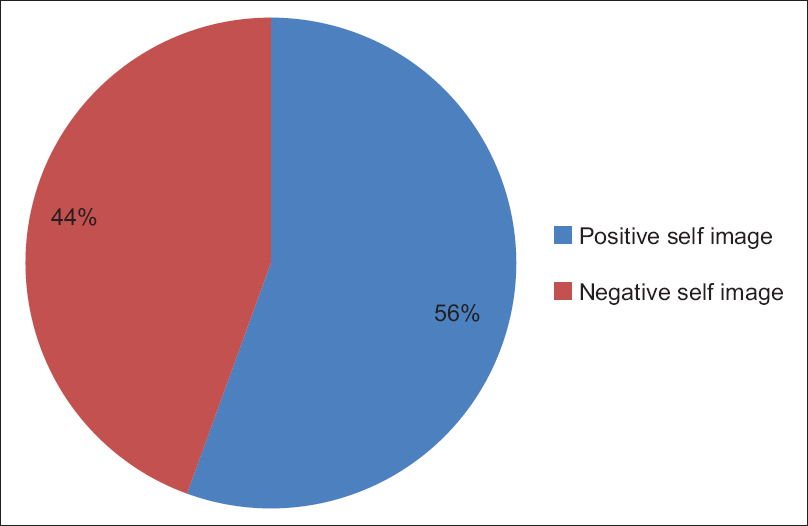

The results of the study showed that 30 (56%) subjects had positive self-image and 24 (44%) had negative self-image. There was a moderate positive correlation between body image and integrity (r = 0.430, P = 0.001), weak positive correlation between body image and self-esteem (r = 0.270, P = 0.049), and no correlation between self-esteem and integrity (r = 0.203, P = 0.141). The participants also scored maximum (24/24) in the areas of body image and self-esteem. Similar findings were also observed in the phenomenological approach. The themes evolved were immaterial of outer appearance and desire of good health to all.

Conclusion:

The illness is long-term and impacts the individual 24 h a day. Understanding patients’ self-concept and living experiences of patients with HNC is important for the health care professionals to improve the care.

Keywords

Head and neck cancer

Mixed method

Self-concept

Self-image

South India

INTRODUCTION

Human beings are always enthusiastic in portraying themselves. Self-concept is generally used to refer how someone discerns and thinks about themselves,[1] and it has persuasive influence in one's life.[2] The concept of “self” is of major interest and is the indispensable human need.[3] It has been always titled that the self-concept is multifaceted.[4] The main facets of self-concept are emotional, intellectual, and functional. The self-concept is unique to individual and changes over time with environmental context.[2] Development of positive or negative self-concept mainly results from physical changes, appearance and performance changes, health challenges, and on the feedback significantly from others. Alteration in health status due to loss or severance of a body part can also affect the self-concept.[2]

Face is recognized as the prime important element of our sense of personality. Enormous importance is placed by individuals on head and neck area than any other parts of the body. The integrity of head and neck is also very much essential for emotional expressions, interaction, and swallowing. Many of the head and neck cancer (HNC) patients cannot hide the side effects of the treatments such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery due to the obvious visibility of the condition and functional difficulties. The distinguishable changes in the appearance, intense changes in taste, swallowing, and speech also lead to awkwardness. Due to these factors, there will be more apprehension, opposition toward disfigurement, and stigmatized in the society among HNC patients.[5]

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This is a mixed method study conducted in two tertiary care hospitals of South India by using a triangulation mixed method design. Both descriptive survey approach and qualitative phenomenological approach were adopted to assess the depth of the self-image of the patients with HNCs. The study was conducted between February 7, 2015, and May 10, 2015. The subjects receiving radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy, during the 4th week of radiation therapy were included in the study. HNC patients with surgical management were excluded from the study. A nested sampling technique was adapted for the mixed method design, i.e., for the descriptive survey design, to assess the self-image of HNC patients, a purposive sampling technique was used. Data were collected among 54 participants. Only female participants those who were included in the quantitative approach and also able to communicate verbally were included in the qualitative phenomenological approach for interviewing by using the semi-structured interview focusing on the self-image. Data saturation was achieved in qualitative phenomenological approach upon interviewing seven participants. Thus, the sample size for the qualitative approach became seven. Hence, the samples of qualitative strand were a subset of the quantitative strand. The quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously by focusing equal importance on both strands. Administrative permission and institutional ethical permission were obtained.

Data were gathered by using self-administered self-image scale and structured interview technique. Self-image scale was a four point likert scale with three sub-domains such as body image, self-esteem, and integrity. The measuring instruments were validated with five subject experts from the field of nursing, oncology, and department of humanities. Reliability of the self-image scale was carried out among 20 subjects. Reliability coefficient was computed by using cronbach alpha, and it was reliable (r = 0.7). Data collected were analyzed by using SPSS 16.0 for quantitative (SPSS Inc., Chicago) and open code software 4.0 (OPC 4.0) for qualitative analysis (ITS and Epidemiology, University of Umea).

Both methods were mixed at the analysis phase of research. That means both quantitative and qualitative data were actually merged in the areas of self-image and the experiences at the analytic phase of the continuum. Qualitative data were transcribed and translated into English and were analyzed by using steps of the Colaizzi process for phenomenological approach. Extraction of sub-themes and categories describing the phenomena was derived.

RESULTS

Description of the self-image of the patients with head and neck cancer

Data in the figure show that majority, i.e., 30 (56%) subjects had positive self-image and remaining 24 (44%) of them had negative self-image [Figure 1].

- Description of the self-image of the patients with head and neck cancer

Similar findings were observed in the phenomenological approach. Subjects mentioned that they were not paying much importance to the external appearance. Instead being in a state of good health was the supreme need. The sub-themes evolved were “immaterial of external appearance” and “desire of good health to all.”

Participant quoted, “I feel I am a good person, I have good qualities… my neighbors say how I got this disease, such a good person, such a helping person… how she got the disease (agony) (pause)….”

Description of the domains of self-image of the patients with head and neck cancer

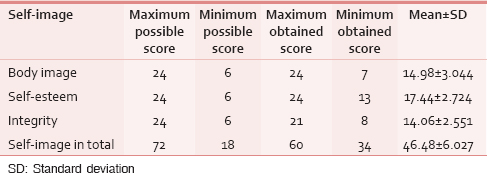

Data in Table 1 show that the mean and standard deviation (SD) of self-esteem, body image, and integrity were 17.44 (2.724), 14.98 (3.04), and 14.06 (6.027), respectively. However, there were also subjects scored maximum scores (24/24) in the areas of body image and self-esteem.

Similar findings were also observed in phenomenological approach. The participants also remained immaterial about external beauty and they felt they are possessing good qualities. Participant A said, “what I have to do with the beauty… if God gives good health… that's enough… that's enough.” Participant B said, “no… (nods the head). What to do with external beauty… health is important… health is required my dear… if health is good we can earn our bread… what to do with beauty? What is there in beauty? However, it is… I am aged now my dear… once if I become all right that's enough… my dear.” Participant C said, “I am aged know… what I have to do with external beauty? (smiles)… health is important… what else to do with beauty?… That too elderly like me… (smiles) if I become all right that's enough… (pause)… I may gain weight after that… when I start eating regularly.” Participant D also does not pay much importance toward external appearance. She said, “I don’t think on that much.” Participant F said, “we are on the earth only for 4 days… if we are healthy that is enough… (pause).”

Description of the relationship among the domains of self-image of the patients with head and neck cancer

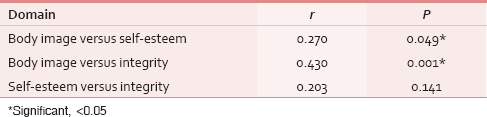

This section presents the description of the relationship between domains of self-image of the patients with HNC, since the data were not following normal distribution. Spearman's rho was computed to assess the relationship between the variables. To assess the relationship between domains of self-image of the patients with HNC, the following null hypothesis was stated.

H01 (Null hypothesis): There will be no significant relationship among the domains of self-image.

The data in Table 2 show that there is a moderate positive correlation between body image and integrity (r = 0.430, P = 0.001) and weak positive correlation between body image and self-esteem (r = 0.270, P = 0.049). Self-esteem and integrity (r = 0.203, P = 0.141) of the patients with HNC were not correlated. Therefore, the research hypothesis is partially rejected and null hypothesis is partially accepted. Thus, it is inferred that the impact on one area of self-image may also have impact on another domain of self-image except for self-esteem and integrity.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed at describing the self-image of the patients by using the mixed method approach. The study provides some important information on the self-image of the HNC patients. Existing reviews show negative self-image, low self-esteem, and transformed self-image among HNC patients. However, the present study findings showed mean and SD of self-esteem of 17.44 (2.724), body image of 14.98 (3.04), and integrity of 14.06 (6.027). These findings show that the domains of self-image are not much affected for the patients with HNC, since the means are above normal for self-esteem and near normal for body image and integrity. Similar experiences in terms of their verbatim supporting the quantitative data were noted among the participants.

A systematic review of qualitative studies was conducted by Nayak et al., 2015,[6] to assess the self-concept of the patients with HNC. This review had only studies conducted in non-Asian continents among both genders of HNC patients. Results showed that there were perceived and transformed changes in self-esteem and changes in self-image or ruptured self-image among HNC patients.[6] However, the subjects included in those studies also underwent surgical management with/without radiation therapy and chemotherapy for HNC. Nevertheless, there was no major difference in the sample characteristics such as age and diagnosis when compared with the present study. In this study, subjects also verbalized that they are not concerned about the external appearance and body image, since they are aged.

This study findings also showed moderate positive correlation between body image and integrity (r = 0.430, P = 0.001) and weak positive correlation between body image and self-esteem (r = 0.270, P = 0.049). As human beings are considered as a system, the impact on one area of self-image may also have an impact on another domain of self.

Feelings of self-consciousness, inadequacy and embarrassment, and unattractiveness as prompted low self-esteem among HNC patients were reported in a qualitative study conducted by phenomenological approach.[7] Another qualitative study was carried out at the United Kingdom to explore and describe the patients’ experiences of changes. The study describes changes in the functions such as eating, drinking, and hearing along with the appearance, which had a great impact on their confidence. The functional difficulties and the physical appearance together impacted on persons change in behavior and attitude.[8]

Some HNC patients felt a loss of dignity and described themselves in denigratory terms due to disfigurement of outer body image. Body image and self-image were also impacted due to disfigurement and altered body functioning such as difficulties in eating, drinking, speaking, and breathing. Hospitalization was aggravating the trauma of change in appearance, sense of loss of self, feeling of incapacitated, and loss of autonomy for HNC patients. HNC patients also portray themselves as “the odd man out” and “visible minority” when standing in public, as disfigurement attracts the attention of society. The patients were also shocked, frightened, and incredulous when they saw themselves in the mirror. A sense of ruptured self-image and a feeling of “no longer the same person” were emerged from HNC patients as a result of disfigurement.[7] However, most of the subjects included in this study underwent surgical treatment such as radical and neck dissection, neck and lateral arm flap, and radical free flap in addition to radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Subjects from both gender and aged between 35 and 71 years were included in the study.

CONCLUSION

The illness is long-term and impacts the individual all day. Understanding patients’ self-concept and living experiences of patients with HNC is important for the health care professionals to improve the care. Thus, the study generates avenues to develop nursing interventions built on patients’ own needs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Nursing Fundamentals: Caring and Clinical Decision. New York: Delmar Cengage Learning; 2003. p. :1551-3.

- 1992. Self-Concept. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; :1. Available from: https://www.books.google.co.in/books

- Aspects of self-concept and their relationship to language performance and verbal reasoning ability. Am J Psychol. 2000;113:621-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial Interventions for Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Available from: http://www.oralcancerfoundation.org/treatment/nursing_part 1.php

- Self concept of Head and Neck cancer patients – A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Sci Res. 2015;4:51-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Looking beyond disfigurement: The experience of patients with head and neck cancer. J Palliat Care. 2014;30:5-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- An exploration of the perceived changes in intimacy of patients’ relationships following head and neck cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:2499-508.

- [Google Scholar]