Translate this page into:

Impact of Health Awareness Campaign in Improving the Perception of the Community about Palliative Care: A Pre- and Post-intervention Study in Rural Tamil Nadu

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sonali Sarkar; E-mail: sarkarsonaligh@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background and Objective:

The only way to provide palliative care to a huge number of people in need in India is through community participation, which can be achieved by improving the awareness of the people about palliative care. We conducted a study to assess the impact of health awareness campaign in improving the awareness of people about palliative care.

Materials and Methods:

This was a pre- and post-intervention study conducted in Kadaperikuppam village of Vanur Taluk in Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu. One respondent each from 145 households in the village was interviewed regarding the knowledge and attitude on palliative care before and after the health awareness campaign using a pretested questionnaire. Health awareness campaign consisted of skit, pamphlet distribution, poster presentation, giving door-to-door information, and general interaction with palliative team in the village.

Results:

The awareness regarding palliative care during the preintervention was nil. After the intervention, it increased to 62.8%. However, there was a decline in the attitude and the interest of the people toward palliative care.

Interpretation and Conclusions:

Health awareness campaigns can increase the awareness of people in the rural parts of the country about palliative care. However, to improve the attitude of the community about delivery of palliative care services, more sustained efforts are required to make them believe that palliative care can be provided by community volunteers also and not necessarily only by professionals.

Keywords

Community-based

Health awareness campaign

Palliative care

Rural India

INTRODUCTION

People with life-limiting diseases including cancer, other noncommunicable diseases, and communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS have pain, other symptoms, and psychosocial distress, which can dramatically decrease the quality of life and place a burden on the economy and on health-care system.[1]

Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families who are facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems.[2]

Those dying from noncommunicable diseases represent around 90% of the burden of end-of-life palliative care.[3] Noncommunicable diseases and injuries account for 52% of deaths in India.[4] However, <1% of those have any access to palliative care.[5] It is estimated that 1 million new cases of cancer occur each year in India, with over 80% presenting at stage III and IV.[6] The need of palliative care in India is immense. Recently, the explosion in HIV/AIDS cases in India has made the requirement for palliative forms of treatment even more acute. 6 Every hour, more than sixty patients die in India from cancer and in pain. But, with a population of over a billion, spread over a vast geographical area, it is difficult for the palliative care programs to reach every nook and corner of the country, especially the rural areas.[7] In 16 states and union territories in India, McDermott et al. in 2008 identified 138 hospice and palliative care services.[8] These are mostly concentrated in large cities, with the exception of Kerala, where they are much more widespread.[8] About 75% of health infrastructure, medical man power, and other health resources are concentrated in urban areas where 27% of the population lives.[9] In the rural areas, a lack of resources, illiteracy, poverty, and lack of awareness about the types of available health care make developing palliative care services a major challenge in India.[10]

Awareness about palliative care is low in India. Even in Kerala with 15 pain and palliative care units functioning in 2008, only 4.2% people in rural areas had some knowledge about palliative care.[11]

In the global scenario, institution-based models of palliative care have not been considered as realistic solutions. Patients with chronic or incurable diseases have medical and nursing problems, which cannot be addressed solely by a doctor/nurse/palliative care center. Issues associated are basically social problems with a medical component. These issues need to be handled by the society; therefore, the community should be in charge of the program.[12]

Achieving community participation in health-related activities has remained a challenge for health programs in India. Although Kerala has exhibited unique standards of community participation in providing and managing palliative care services through neighborhood network of palliative care, the same has yet not been replicated in the rest of India. High levels of awareness of the need and motivation among community volunteers for providing palliative care are required. Such community mobilization is possible through health awareness campaigns using various methods of health education such as short films, street plays, hand-outs, and medical camps. We conducted this study in a village in Tamil Nadu to assess the impact of such a health awareness campaign on the awareness of the people about palliative care. The overall aim of our study was to improve the perception of the people about the palliative care through health awareness campaign.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a pre- and post-intervention study.

Setting

The study was undertaken at Kadaperikuppam Village in the Vanur taluk of Villupuram district in Tamil Nadu.

Sample size

Considering the prevalence of awareness about palliative care to be 4% in the rural population,[11] we expected a minimum improvement of awareness to 15% of the population after the awareness campaign. With 80% power and α = 0.05 (5%), the sample size was calculated to be 128 using the statistical software STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). In expecting the loss of number of people to follow-up, we increased the sample size by approximately 10% to 145 households.

Sampling technique

Vanur taluk in the district of Villupuram was selected purposively as it is closer to the medical college. This taluk has nine villages under its jurisdiction.

Out of which Kadaperikuppam village was chosen randomly. This village is about 17 Km away from the institution in Puducherry. The village is naturally divided into three big areas having approximately 420 households and a total population of 2007.

First house of the first street was selected in each area. Consecutive houses in the street and the adjacent streets which were not locked were selected till a target of 48 houses per area was achieved. In the process, almost all the major streets in the three areas were covered. The final sampling unit was a household, but an individual in the household was interviewed. The oldest member or any adult female member of the household who was able to give information about all members of the family was interviewed. A total of 145 households with a population of 601 were selected for the study.

Inclusion criteria

Oldest person or any female more than 18 years of age who was present at the time of visit by the interviewer in the selected households.

Study period

The study period was from April 1, 2015 till the end of June 2015.

Procedure

Preintervention

This study was done under a project of community-based palliative care initiated by the parent institution Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER) and Tamil Nadu Institute of Palliative Medicine (TNIPM) in Villupuram district of Tamil Nadu.

The investigator traveled with the team from the institute consisting of palliative nurse, palliative social worker, doctor, volunteer, village head, and faculty in-charge of the project. The oldest member or any woman in the household, who was able to give information about all members of family was interviewed.

Preintervention survey was conducted through an interview using a pretested

Intervention

The heath awareness campaign was conducted in the village. Door-to-door information was passed on through the palliative care nurses. Invitation was printed in pamphlets and was given door-to-door in the whole village. Banners were placed in the village to increase the awareness about the awareness program. Cultural night was held on Sunday evening so that maximum number of people in the village could attend. In the cultural night, a skit was performed, followed by the speech and interaction of palliative care team with village head and people in the village. Participants were made aware of the concept of palliative care and about the role of the community in providing palliative care services. This information was expected to spread to the community through these participants. The overall aim was to improve the community participation and identification of volunteers for providing home-based palliative care. At the end of the program, 8 volunteers were selected from the village and who would undergo training by the JIPMER-TNIPM team.

Postintervention

Following the intervention, a gap of 2 weeks was given for man-to-man transmission of information. A postintervention survey was conducted by the investigator among the same participants (who were interviewed in the preintervention survey) with the

If the participants were not available during the postintervention visit, subsequent visits were made by contacting them through their mobile phone number and were interviewed during their leisure time.

Variables included in questionnaire

-

Sociodemographic variables: Age, gender, education, occupation, socioeconomic status, and type of family

-

Medical details: Morbidities and disabilities

-

Need for palliative care in respondents or any member of the household

-

Awareness regarding palliative care

-

What is palliative care (components?)

-

Conditions requiring palliative care

-

Who can provide palliative care?

-

Role of community volunteer?

-

Perceptions of the need of palliative care in the community

-

Perception regarding the best place such care can be provided

-

Perception regarding the role community can play in providing palliative care to the needy members of the society.

Statistical analysis

The data collected were entered in MS Excel, and analysis was done using statistical software IBM SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). All the participant characteristics were considered as categorical variables and described as proportions. Awareness regarding palliative care was presented as present or absent. Among those who were aware, questions on components, conditions, and providers of palliative care were dealt with separately as “aware” and “not aware.” Perception of the need of palliative care by the community was presented as “felt need” and “no need.”

Ethical issues

The protocol was approved by the JIPMER Scientific Advisory Committee and ICMR, and then approval was taken by the Institute Ethics Committee (human studies) before starting the study.

Interviews of the participants were taken after explaining the study procedures and obtaining the written informed consent. Confidentiality of the data was maintained.

RESULTS

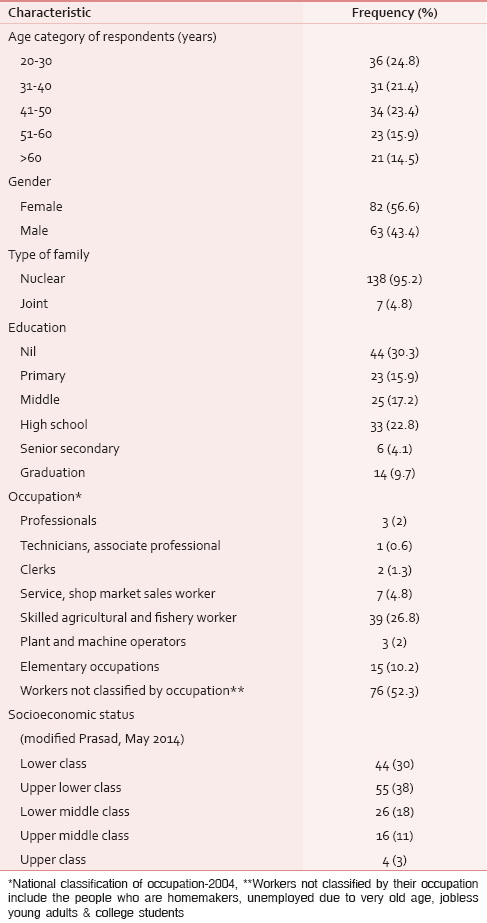

A total of 145 participants were interviewed. There were more females than males in the study population, almost all belonging to nuclear families. Majority (68.2%) were from the lower most classes of the socioeconomic groups with 30% without any education [Table 1].

In two out of 145 households (601 persons), there were two individuals who were in need of palliative care (3.3/1000 population). One of them was having tuberculosis (TB) and the other person was having fracture femur. They were bedridden, and had problems such as pain, cough, breathlessness, fatigue, loss of appetite, and were dependent on their family members for their daily living activities. The pain was managed by femur fracture patient by medicine whereas no management was done for TB patient. No counseling was given to the patients or to the caregivers. Both had financial problems, while the TB patient had social problems too.

In the preintervention survey, no one in the village had heard the term “palliative care/end of life care/home care for bedridden people/community-based care.” The campaign was attended by at least one member in 83 out of the 145 (57.2%) households. After the campaign, 91 participants (62.8%) were aware of the term palliative care.

In 75 (82.41%) out of these 91participants, the source of information was the campaign and in the rest 16 (17.58%), it was the neighbors.

At the end of the campaign, eight participants out of the 83 families who attended the program were still not aware of the term “palliative care/end of life care/home care for bedridden people/community-based care,” as either they did not attend the complete program or the information about palliative care was not passed on to the participant by their family members who attended the program. Among those who did not attend the campaign (62), the reasons given for not being able to attend were unavailability or other engagements. Only nine participants said that they were not aware of the program [Table 2].

Among those who answered for the providers of palliative care (85/91), all knew only about doctors and/or nurses. Nobody mentioned about volunteers. Nearly, 88% were aware of the ability of palliative care in addressing physical, psychological, social, and spiritual problems of the patients, and majority (56%) were aware about the financial benefits to the family. However, 75% said that a volunteer can provide palliative care, when given options to choose the work of volunteers. Only 3.3% mentioned community as the place where this can be provided [Table 3].

Cancer was most commonly quoted as the disease requiring palliative care. Nearly, 20% also mentioned hypertension and diabetes. Other conditions said by the participants were fever, pain, heart disease, unable to walk, and skin disease [Table 4].

Attitude regarding palliative care showed a decline for all five questions. Maximum decrease was there for the domains involving community support in financial, psychological, and social needs of people requiring palliative care and whether the participants would like to volunteer for palliative care services [Table 5].

DISCUSSION

Among the 145 participants from 145 households having a population of 601 from the village of Kadaperikuppam in Tamil Nadu, awareness regarding palliative care was nil during the preintervention survey. Joseph et al. in 2009 reported better awareness of palliative care in the rural area of Ernakulam district of Kerala.[11] Although the burden of diseases requiring palliative care services is not less in Tamil Nadu, 3.3/1000 population in this sample households, the concept of palliative care is new. Following the intervention, 62.8% of the participants became aware of the term. As the baseline awareness was nil, this is considered a significant increase, and no statistical tests could be performed to find out the factors that were associated with increase in awareness. The effect of such palliative care awareness campaigns in improving the knowledge and understanding of the topic among general population in India is not reported in scientific literature. However, awareness campaigns have been found to be successful for topics such as menstrual hygiene where Dongre et al. demonstrated in 2007 a significant increase in the awareness of menstruation among rural adolescent girls (55%) after the campaign compared to the baseline (35%).[13] Educational campaigns have also resulted in higher use of contraceptives for spacing among registered pregnant women in India as reported by Sebastian et al. in 2010.[14] In our study, we found the campaign to be effective in increasing the awareness of the rural people about palliative care.

Even though there was an increase in the awareness of the topic, the intervention was not useful in impressing upon the people the role of volunteers and community support in providing palliative care. People continued to think that doctors and/or nurses can provide palliative care services and the majority (52%) still felt that such services can be provided in hospitals or clinics.

The attitudinal change following the intervention was contradictory to the expectation. In the preintervention survey, the positive attitude of the participants is unreliable and questionable as none were aware of palliative care. Once they came to know the content and purpose of palliative care services from the campaign, their attitude in the postintervention survey appeared to have deteriorated. Being completely new to the concept of palliative care, it is not unexpected that people are skeptical about the role of community in providing support to patients in need of palliative care and that such compassionate communities do exist.

Some qualitative interviews among the participants showed that people had expected that these services would be provided through well-trained doctors or nurse only by means of clinic or through regular home visits by a doctor or nurse. After the campaign, when the people came to know that the community-based palliative care was to be started in their village through volunteers, they were disappointed. The decline in the proportion of participants agreeing to be volunteers may be attributed to the fact that after the campaign, they were aware of the diseases and type of services which constitutes the palliative care. Some of the participants who volunteered reported that their lack of education and advanced age would be a barrier in volunteering. Some of the volunteers who were interviewed did not have confidence in themselves to provide such care and expected the doctors and nurses to do the job. However, the proportion of participants who opined positively to whether such services will be utilized once started in their community (86.2%) and whether they wanted to know more about the palliative care services (80.7%) during the postintervention survey was good. The proportion of participants with positive attitude should be considered as an improvement from nil in the preintervention survey and is an impact of the awareness campaign.

CONCLUSION

The awareness campaign, which was the intervention in this study, was effective in increasing the awareness of people in the village Kadaperikuppam of Tamil Nadu on palliative care from nil to 62.8%.

However, as the topic and concept of palliative care, especially community-based care through volunteers is new to this community, some participants had doubts. Attitudinal change requires more persistent efforts and people may be better convinced when they witness palliative care services being effectively provided through volunteers and community coming forward to support such services.

SUMMARY

This study was conducted to assess impact of the health awareness campaign in improving the awareness about palliative care in Kadaperikuppam village in Villupuram district of Tamil Nadu. The health awareness campaign consisted of door-to-door visit by nurses, distribution of pamphlets, a cultural night with a skit performance, and speeches by the palliative care team. This intervention increased the awareness of the community on palliative care, but the change in attitude was low.

SUGGESTIONS

Health awareness campaigns consisting of posters, role plays, interactive sessions, door-to-door pamphlet distribution, and imparting of information can increase the awareness of people in the rural parts of the country about palliative care. But, to improve the attitude of the community about delivery of palliative care services, more sustained efforts are required to make them believe that palliative care can be provided by community volunteers also and not necessarily only by professionals.

Financial support and sponsorship

We acknowledge the financial support from ICMR. This study was done as STS project under ICMR.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 2012. National Palliative Care Strategy – Pallium India. Available from: http://www.palliumindia.org/cms/./National-Palliative-Care-Strategy-Nov_2012.pdf

- WHO | Cancer | Palliative. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. 2015. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance, WHO. Available from: http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden of NCDs, Policies and programme for prevention and control of NCDs in India. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36(Suppl 1):S7-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Association of Palliative Care. In: Handbook for Certificate Course in Essentials of Palliative Care (4th Revised Edition). Lacknow: Indian Association of Palliative Care; 2012. p. :10.

- [Google Scholar]

- The palliative care movement in India: Another freedom struggle or a silent revolution? Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:10-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospice and palliative care development in India: A multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:583-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of palliative care in India: An overview. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12:241-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study to assess the awareness of palliative care between urban and rural areas of Ernakulum district, Kerala, India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:122-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of community-based health education intervention on management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health Popul. 2007;9:48-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Promoting healthy spacing between pregnancies in India: Need for differential education campaigns. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:395-401.

- [Google Scholar]