Translate this page into:

Effects of an integrated Yoga Program on Self-reported Depression Scores in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Conventional Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Address for correspondence: Dr. Raghavendra Rao Mohan; E-mail: raghav.hcgrf@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aim:

To compare the effects of yoga program with supportive therapy on self-reported symptoms of depression in breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment.

Patients and Methods:

Ninety-eight breast cancer patients with stage II and III disease from a cancer center were randomly assigned to receive yoga (n = 45) and supportive therapy (n = 53) over a 24-week period during which they underwent surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) or chemotherapy (CT) or both. The study stoppage criteria was progressive disease rendering the patient bedridden or any physical musculoskeletal injury resulting from intervention or less than 60% attendance to yoga intervention. Subjects underwent yoga intervention for 60 min daily with control group undergoing supportive therapy during their hospital visits. Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) and symptom checklist were assessed at baseline, after surgery, before, during, and after RT and six cycles of CT. We used analysis of covariance (intent-to-treat) to study the effects of intervention on depression scores and Pearson correlation analyses to evaluate the bivariate relationships.

Results:

A total of 69 participants contributed data to the current analysis (yoga, n = 33, and controls, n = 36). There was 29% attrition in this study. The results suggest an overall decrease in self-reported depression with time in both the groups. There was a significant decrease in depression scores in the yoga group as compared to controls following surgery, RT, and CT (P < 0.01). There was a positive correlation (P < 0.001) between depression scores with symptom severity and distress during surgery, RT, and CT.

Conclusion:

The results suggest possible antidepressant effects with yoga intervention in breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment.

Keywords

Behavioral intervention

Cancer

Depression

Relaxation

Yoga

INTRODUCTION

Psychosocial morbidity is common in breast cancer patients after mastectomy and increased during radiotherapy (RT) and chemotherapy (CT), wherein the majority of patients reported some degree of depression, anxiety, social dysfunction, and inability to work.[123] Anxiety and depression are the commonest psychiatric problems encountered in cancer patients. It has been repeatedly acknowledged that many psychiatric disorders in cancer patients are not detected, diagnosed, or treated.[4] The prevalence of depression in cancer patients ranges from 4.5 to 58%.[5] Patients with breast cancer undergoing radiation treatment also report anxiety and depression before, during, and after the treatment.[67] The prevalence of anxiety and depression in Indian cancer patients in Bangalore undergoing radiation treatment was 64 and 50%, respectively.[6] There is a very high correlation between anxiety and depression in cancer patients.[8]

Many factors that contribute to development of depression are related to cancer itself. This includes reaction to disfigurement or mutilating surgeries, for example, mastectomy vs lumpectomy patients, several somatic symptoms such as pain,[9] medications, and chemotherapeutic agents.[10] Although recent clinical studies have not found a relationship between depression and cancer outcome.[11] Studies show that depression influences treatment-related distress in cancer patients[8] and warrant clinical attention because of their clear adverse effects on the quality of life of cancer patients. Other studies have shown depression to be related to prognostic indicators of clinical and pathological response to CT,[12] decreased survival age, abnormal diurnal cortisol rhythms in metastatic breast cancer patients,[13] and predictor of lower mortality.[14]

Various behavioral interventions have been used successfully to alleviate depression in these patients. Possible explanations for effects of these interventions in improving quality of life (Qol) outcomes and reducing treatment-related distress in these patients have been attributed to: (i) Decrease in anxiety and affective states,[15] (ii) resorting to more active–behavioral and active–cognitive coping lifestyles,[16] and (iii) reinforcement of social support and stress reduction.[17] While standard psychotherapy approaches such as cognitive behavioral techniques or supportive expressive group therapy encourage problem solving, sharing, and support; they do not include noncognitive resources such as body and breath awareness, postures, meditation, or spiritual exploration. It is here that complementary and alternative medicine approaches such as yoga may be helpful.[18]

Yoga as a complementary and mind body therapy is being practiced increasingly in both Indian and western populations. It is an ancient Indian science that has been used for therapeutic benefit in numerous healthcare concerns in which mental stress was believed to play a role.[19] Earlier studies have shown beneficial effects with yoga intervention in modulating depression in both healthy volunteers[2021] and those with established psychiatric diagnoses of depression.[2223] However, results from breast cancer patients are mixed.[2425]

Though most of these studies lack effective controls, have small sample size, use different types of yoga intervention, and depression scales; they nevertheless show beneficial antidepressant effects with yoga intervention.[262728]

In an earlier study of yoga in a population of cancer patients in India[2930] undergoing radiation treatment; there was an overall improvement in quality of life with patients reporting increased appetite, improved sleep, improved bowel habits, a feeling of peace, and tranquility. However, in this study, yoga was integrated with psychotherapy and this study lacked effective controls and involved heterogeneous cancer population. Yoga with strong cultural and traditional roots in India has a mass appeal. The purpose of the current trial was to study whether a support intervention based on use of a widely used mind/body and psychospiritual intervention such as yoga would be a viable alternative to standard “supportive therapy” sessions in breast cancer outpatients undergoing conventional treatment. We therefore hypothesized that an integrated yoga-based stress reduction program would help reduce patient's self-reported depression during conventional cancer treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This randomized controlled trial evaluated the effects of yoga intervention versus supportive therapy in 98 newly diagnosed stage II and III breast cancer patients undergoing surgery followed by adjuvant RT and/or CT. Ethical committee of the recruiting cancer center approved this study. Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (i) Women with recently diagnosed operable breast cancer, (ii) age between 30 and 70 years, (iii) Zubrod's performance status 0–2 (ambulatory > 50% of time), (iv) high school education, (v) willingness to participate, and (vi) treatment plan with surgery followed by either or both adjuvant RT and CT. Patients were excluded if they had (i) a concurrent medical condition likely to interfere with the treatment, (ii) any major psychiatric, neurological illness, or autoimmune disorders, and (iii) secondary malignancy. The details of the study were explained to the participants and their informed consent was obtained.

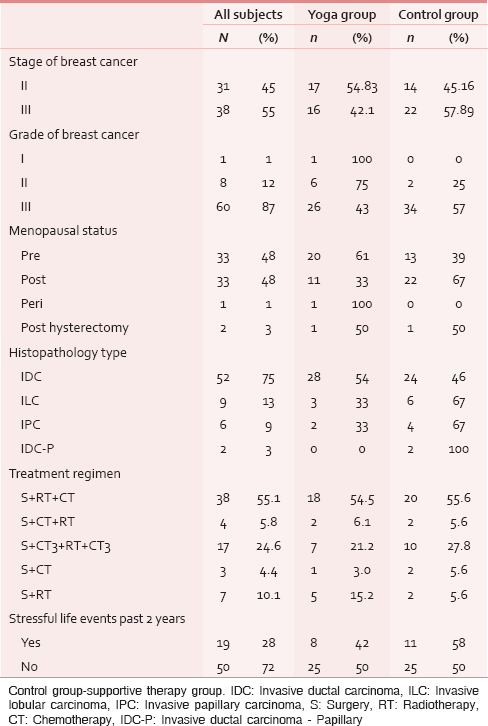

Baseline assessments were done on 98 patients prior to their surgery. Sixty-nine patients contributed data to the current analyses at the second assessment (post-surgery-4 weeks after surgery), 67 patients during and following RT, and 62 patients during and following CT. The reasons for dropouts were attributed to migration to other hospitals, use of other complementary therapies (e.g. Homeopathy or Ayurveda), lack of interest, time constraints, and other concurrent illnesses. However, the order of adjuvant treatments following surgery differed among the subjects [Table 1]. There were four to six assessments depending on the treatment regimen. The assessments were scheduled at pre- and post-surgery; pre-, mid-, and post-RT, and CT. Moreover, all participants in the study received the same dose of radiation (50c Gy over 6 weeks) and prescribed standard CT schedules (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluororacil (CMF) or fluroracil, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide (FAC).

Measures

At the initial visit before randomization demographic information, medical history, clinical data, intake of medications, investigative notes, and conventional treatment regimen were ascertained from all consenting participants. Participants completed the Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) that consists of a set of 21 questions.[31] The questionnaire was translated to local language (Kannada) and the same was validated. This is a self-report measure used to assess behavioral manifestations of depression having reliability between 0.48 and 0.86 and a validity of 0.67 with diagnostic criteria.

Subjective symptom checklist was developed during the pilot phase to assess treatment-related side effects, problems with sexuality and image, and relevant psychological and somatic symptoms related to breast cancer. The checklist consisted of 31 such items each evaluated on two dimensions; severity graded from no to very severe (0–4), and distress from not at all to very much (0–4). These scales measured the total number of symptoms experienced, total/mean severity and distress score, and was evaluated previously in a similar breast cancer population.[32]

Randomization

Randomization was performed using opaque envelopes with group assignments, which were opened sequentially in the order of assignment during recruitment with names and registration numbers written on their covers. Participants were randomized at the initial visit before starting any conventional treatment. Following randomization participants underwent surgery followed by either RT or CT or both and was followed-up with their respective interventions.

Interventions

The intervention group received “integrated yoga program” and the control group received “supportive therapy” both imparted as individual sessions. While the goals of yoga intervention were stress reduction and appraisal change, the goals of supportive therapy were education, reinforcing social support, and coping preparation.

The yoga practices consisted of a set of asanas,[8] breathing exercises, Pranayama (voluntarily regulated nostril breathing), meditation, and yogic relaxation techniques with imagery.

The sessions began with didactic lectures and interactive sessions on philosophical concepts of yoga and importance of these in managing day-to-day stressful experiences (10 min) beginning every session. This was followed by a preparatory practice (20 min) with few easy yoga postures, breathing exercises, pranayama, and yogic relaxation. The subjects were then guided through any one of these meditation practices for next 30 min. This included focusing awareness on sounds and chants from Vedic texts,[33] or breath awareness and impulses of touch emanating from palms and fingers while practicing yogic mudras, or a dynamic form of meditation which involved practice with eyes closed of four yoga postures interspersed with relaxation while supine, thus achieving a combination of both “stimulating” and “calming,” practice.[34] The participants were also informed about practical day-to-day application of awareness and relaxation to attain a state of equanimity during stressful situations and were given homework in learning to adapt to such situations by applying these principles.

Subjects were provided audiotapes of these practices for home practice using the instructors voice so that a familiar voice could be heard on the cassette. Subjects underwent in person sessions during their hospital visits and stay and were asked to practice at home on remaining days. Their instructors through telephone calls, weekly house visits, and daily logs monitored their home practice on a day-to-day basis. The subjects were required to practice yoga for 1 h at least thrice a week. One yoga therapist and one trained counselor were involved in imparting their respective interventions. Both had master's degree in their respective fields.

The control intervention consisted of supportive-expressive therapy with education as a component.[35] Supportive counseling sessions as control intervention aimed at enriching the patient's knowledge of their disease and treatment options, thereby reducing any apprehensions and anxiety regarding their treatment and involved interaction with the patient's spouses. The supportive-expressive therapy as a control intervention involved creating a supportive environment to facilitate the patients to express their problems, strengthen their relationships in the family and community, and find meaning in their lives. The intervention was unstructured, with therapists trained to facilitate discussion of the following themes in an emotionally expressive rather than a didactic format: (i) Addressing concerns regarding fears of toxicity, image change, resulting from treatment;(ii) improving support and communication with family and friends; (iii) integrating a changed self and body image; and (5) improving communication with physicians;(6) allaying fears of recurrence, progression, and death and learning to cope with them.

We chose to have this as a control intervention mainly to control for nonspecific effects of the yoga program that may be associated with adjustment such as attention, support, and a sense of control. This counseling was imparted during their hospital visits and was extended over the course of their adjuvant RT and CT cycles (once in 10 days, 30 min sessions) and participants were encouraged to contact their counselor whenever they had any concerns or issues to discuss. Similar supportive sessions have been used successfully as a control comparison group to evaluate psychotherapeutic interventions[3637] and similar coping preparations have been effective in controlling CT-related side effects.[38]

The investigating team did not have any role in imparting intervention. The yoga therapists were not involved in taking assessments.

Statistical methods

Earlier studies have reported large effect sizes (>1) for depressive symptoms with both yoga and behavioral interventions.[3940] We therefore chose to have a conservative estimate of effect size (standardized difference d) of 0.8 for our study. The sample size needed in our study was based on formula; n = number of groups/d2 × C p, power, where, d is the standardized difference and C p, power is a constant defined by values chosen for P value and power. Considering P at 0.05 and 80% power, the C p, power value is 7.9[41] and standardized difference d as 0.8; going by the formula we have n = 2/0.8 2 × 7.9 = 25 subjects in each arm. Taking into consideration a dropout rate of 25% and considering that intervention was for a different population (cancer patients) with a control intervention, we chose to have approximately 55 subjects in each arm.

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20.0 for PC windows 2000. Study participants underwent surgery, RT, and CT and interventions were compared for each of these treatments. Mean scores for Beck's depression scores was calculated for the complete sample. Since order of their adjuvant treatment differed, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was done to compare groups at each follow-up assessment using the baseline pre surgery measure as a covariate. There were 12 dropouts in yoga and 17 in control group, the reasons for dropouts are given in trial profile. Alternatively, intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses were done using the initially randomized sample where in the baseline value of noncompleters was carried forward to replace their missing values at subsequent assessments. This was done to assess the potential impact of the missing data on the results. Simple Pearson correlation analyses was used to study the bivariate relationships between depression scores and treatment related symptom severity and distress at various conventional treatment intervals (post-surgery/mid RT/mid CT).

RESULTS

The groups were similar with respect to sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Though there was heterogeneity with respect to treatment regimen, this distribution did not differ across groups [Table 1]. There were no dropouts due to injuries due to their participation in the study.

Beck's depression scores

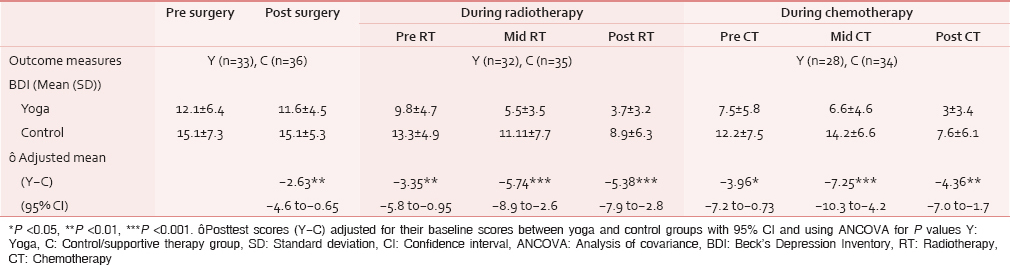

Both the groups reported decrease in their depression with time. Analysis of covariance was done comparing follow-up measures between yoga and control groups controlling for baseline differences. Analysis of covariance using baseline depression scores as a covariate showed significant decrease in depression following surgery (F (65) =7.06, P = 0.01), before RT (F (62) =7.77, P = 0.007), and following RT (F (62) =17.35, P < 0.001) in the yoga group as compared to controls. The yoga group also showed decrease in depression score before CT (F (57) =6.02, P = 0.02), and after CT (F (57) =10.90, P = 0.002) as compared to controls. The decrease in depression became more evident during treatment with significant decrease during RT (F (62) =13.32, P = 0.001) and CT (F (57) =22.3, P < 0.001) [Table 2].

ITT analyses done on the initial randomized sample showed significant decreases in depression scores before (F (1, 91) =6.67, P = 0.01) and during RT (F (1, 91) =6.28, P = 0.01) and before (F (1, 86) =3.88, P = 0.05) and during CT (F (1, 86) =12.8, P = 0.001) only.

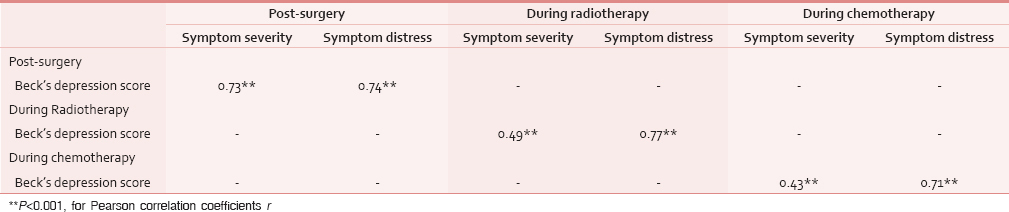

There was a positive significant correlation between depression scores with symptom severity and distress following surgery, during RT and CT [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

We compared the effects of a 24-week yoga program with supportive therapy in 98 recently diagnosed breast cancer outpatients undergoing surgery, RT, and CT. The results suggest an overall decrease in depression scores with time in both the groups. Yoga intervention decreased depressive symptoms more than the controls from their baseline means by 42% following surgery, 28.1 and 28.5% during and following RT, respectively, and 39.5 and 29.2% during and following CT, respectively. Our results are consistent with other studies using relaxation techniques and adjuvant psychological therapy that have shown a similar decrease in depression in these populations.[36] The effect size for decrease in self-reported depressive symptoms using BDI in our study was large (>0.8). In the earlier study using mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in cancer patients the effect size for depression was 0.3 using the subscale of Profile of Mood States (POMS).[25] However, earlier studies using behavioral therapy[39] and yoga[40] have reported large effect sizes (>1) for their respective interventions. This large effect size could partly be due to the fact that, BDI has limitations in subjects with physical health problems and has less test retest reliability on repeated measurements.[42] Irrespective of the magnitude of effect size, our study shows that yoga is beneficial in reducing self-reported symptoms of depression and numerous studies have reported beneficial antidepressant effects with similar stress reduction interventions such as relaxation training in cancer patients.[41]

Stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression[43] and an extensive literature has documented the association of depression with elevated cortisol levels;[44] various conceptual models have been proposed such as the allostatic load model and posttraumatic phenomenology to explain the relationships between stress and neuroendocrine dysregulation.[45]

Overall, the antidepressant effects of yoga program could be attributed to stress reduction rather than mere social support and education. This is consistent with earlier studies that have shown better results with stress reduction than purely supportive interventions.[4647]

The antidepressant effects of yoga intervention could be explained by reduction in the levels of psychophysiological arousal such as decrease in sympathetic activity,[20] balance in the autonomic nervous system responses,[48] alterations in neuroendocrine arousal,[4950] and decrease in morning cortisol.[40]

Scores on self-reported symptoms of depression correlated directly with symptom severity and distress at various stages of conventional treatment further supporting the idea that reductions in stress could contribute to decrements in treatment related distress, outcomes, and depression in cancer patients.[51] We have shown earlier that yoga has been helpful in reducing both post CT nausea and anticipatory nausea and vomiting. This has been attributed to stress reduction effects of yoga intervention.[52]

In our study, depression scores of subjects varied with treatment intervals and time similar to earlier observations in cancer patients.[5354]

One of the major limitations of the study was not tailoring the control intervention to that of Yoga intervention. While yoga group underwent intervention at least three times a week, the control group had intervention only once in 10 days. It may be argued that yoga group received more attention than the supportive therapy group and this could have contributed towards a placebo effect. However, unlike other studies using waitlisted controls, the control group here also received supportive therapy sessions. These sessions were used only with an intention of negating the confounding variables such as social support, instructor-patient interaction, education, and attention that are known to improve the psychological and social functioning in cancer patients.[37] Another objective of using social support as a control was with a view of analyzing and identifying the effects of stress reduction conferred by yoga intervention versus a purely supportive intervention on outcome measures. Yoga is a mind body intervention and as such it is difficult to tailor an active comparator arm for this intervention. Moreover, earlier studies have also demonstrated that placebo effects caused due to attention is unfounded in subjects with melancholia.[55] We chose to have individual therapy sessions as against group practice, as individual sessions also helped to understand the specific needs and concerns of participants and monitor individual progress in practice, thereby reducing the confounding effects of being in a group.[56]

Secondly, some of the symptoms on BDI also mimic symptoms of cancer disease and treatment like feeling down, lack of energy or fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, etc., which could have contributed to increased scores on BDI. However, since all patients underwent conventional treatment, any increase in BDI could have had a floor effect across the entire study group.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the study shows benefit finding for reducing self-reported depression scores in operable breast cancer patients undergoing cancer directed treatment. However, future studies should assess role of yoga in managing clinical depression in this population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study is funded with grants from Central Council for Research in Yoga and Naturopathy, Dept of AYUSH, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India. We are thankful to them for their support.

Source of Support: Grant from Central Council for Research in Yoga and Naturopathy (CCRYN), Department of AYUSH, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Quality of life in breast cancer survivors as identified by focus groups. Psychooncology. 1997;6:13-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post mastectomy coping strategies and quality of life. Health Psychol. 1983;2:117-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial implications of adjuvant chemotherapy. A two-year follow-up. Cancer. 1983;52:1541-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;249:751-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Absence of major depressive disorder in female cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3:1553-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Levels of anxiety and depression in patients receiving radiotherapy in India. Psychooncology. 1996;5:343-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceived symptoms and quality of life in women with breast cancer receiving radiation therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2000;4:78-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concordance of depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. Psychol Rep. 1984;54:588-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mood states of oncology outpatients: Does pain make a difference? J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:120-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial aspects of cancers in women. Bangalore: Department of Psychiatry, NIMHANS; 1998.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial correlates of survival in advanced malignant disease? New Engl J Med. 1985;312:1551-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological factors predict response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in women with locally advanced breast cancer. Psychooncology. 1997;6:242-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early mortality in metastatic breast cancer patients with absent or abnormal diurnal cortisol rhythms. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:994-1000.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological predictors of survival in cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Psychother Psychosom. 1987;47:65-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychotherapy, stress, and survival in breast cancer. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications; 1994. p. :123-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychol. 1995;14:101-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial aspects of breast cancer treatment. Semin Oncol. 1997;24(1 Suppl 1):S1.

- [Google Scholar]

- The efficacy of a mind -body-spirit group for women with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:238-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of yogic exercises on physical and mental health of young fellowship course trainees. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;45:37-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- A yoga intervention for young adults with elevated symptoms of depression. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:60-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of yoga on mood in psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005;28:399-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Sahaj Yoga on depressive disorders. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;49:462-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: Physical and psychological benefits. Psychooncology. 2006;15:891-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:613-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yoga therapy for breast cancer patients: A prospective cohort study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:227-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of yoga exercise on improving depression, anxiety, and fatigue in women with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Res. 2014;22:155-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1058-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological supportive therapy for cancer patients. Indian J Cancer. 1982;20:268-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Behavioural management of patients with cancer. Bangalore: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; 1996.

- [Google Scholar]

- Autonomic changes while mentally repeating two syllables-one meaningful and the other neutral. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;42:57-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxygen consumption and respiration following two yoga relaxation techniques. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2000;25:221-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized trial of group psychosocial support in metastatic breast cancer: The BEST study. Breast-Expressive Supportive Therapy study. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;22:91-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adjuvant psychological therapy for patients with cancer: A prospective randomized trial. Br Med J. 1992;304:675-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Group coping skills instruction and supportive group therapy for cancer patients: A comparison of strategies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:802-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparing patients for cancer chemotherapy: Effect of coping preparation and relaxation interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:518-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Behaviour therapy for depressed cancer patients in primary care. Psychotherapy. 2005;42:236-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidepressant efficacy and hormonal effects of Sudarshana Kriya Yoga (SKY) in alcohol dependent individuals. J Affect Disord. 2006;94:249-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Major depression and the stress system: A life span perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:565-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: A meta-analytical review. Psycho-oncology. 2001;10:490-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- The potential role of excessive cortisol induced by HPA hyperfunction in the pathogenesis of depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1995;5:77-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stress and allostatic load: Perspectives in psycho-oncology. Bull Cancer. 2006;93:289-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of meditation-relaxation and cognitive/behavioural techniques for reducing anxiety and depression in a geriatric population. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1989;22:231-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;334:888-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physiological changes in sports teachers following 3 months of training in Yoga. Indian J Med Sci. 1993;47:235-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of running and meditation on beta-endorphin, corticotrophin-releasing hormone and cortisol in plasma, and on mood. Biol Psychol. 1995;40:251-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Hatha yoga and African dance on perceived stress, affect, and salivary cortisol. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:114-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety as a predictor of behavioural therapy outcome for cancer chemotherapy patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:860-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of an integrated yoga programme on chemotherapy induced nausea and emesis in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16:462-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological morbidity in thefirst year after breast surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1992;18:327-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fear of recurrence, breast-conserving surgery, and the trade-off hypothesis. Cancer. 1992;69:2111-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does melancholia predict response in major depression? J Affect Disord. 1990;18:157-65.

- [Google Scholar]