Translate this page into:

Perspective of Orthopedists on Pain Management in Osteoarthritis: A Qualitative Study

Address for correspondence: Dr. Shoba Nair; E-mail: nair.shoba@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative disorder characterized by pain, stiffness, and loss of mobility of the joint. As the most prevalent form of arthritis and a leading cause of impairment, it is imperative to understand the treating doctor's perception of pain relief among these patients.

Objectives:

To assess orthopedists’ perspectives on pain management in OA.

Materials and Methods:

In this qualitative study, a guide-based interview was conducted on 15 orthopedists of a tertiary care hospital and audio-recorded simultaneously. A grounded theory approach was adopted for data transcription with an inductive approach for thematic manual analysis.

Results:

Five themes emerged - (1) quality of life: OA produces significant disease burden causing severe impairment; (2) pain management: although patients usually demand immediate pain relief, a multipronged approach to treatment emphasizing on physiotherapy and surgery rather than analgesics is needed. Most participants preferred individual discretion while others felt the need for systematizing pain management; (3) precautions/side effects of treatment: paracetamol is often prescribed due to its better benefit − adversity profile as compared to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and weak opioids; (4) barriers: participants expressed several barriers to optimal pain management; (5) counseling: Participants concurred that counseling would improve patients’ quality of life.

Conclusions:

Participants agreed that OA being associated with debilitating pain and impairment requires optimal pain management for improving patients’ quality of life. As crucial as counseling is, it is often compromised due to the large outpatient load. The doctors concurred that a multi-disciplinary team approach is needed to integrate and optimize pain management in OA.

Keywords

Osteoarthritis

Orthopedist

Pain

Pain management

Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a multifactorial chronic degenerative disorder causing severe debilitating pain and loss of physical function. Unfortunately, most chronic arthritis patients cannot achieve a state of complete recovery and continue to suffer from pain and handicap.[1] OA of the knee and hip are the most common causes of musculoskeletal disability among the elderly.[23]

Pain is a global medical problem whose management continues to challenge doctors despite scientific and technological breakthroughs.[4] Pain relief has been put forward as a fundamental human right, giving health-care professionals the obligation to provide adequate pain relief to their patients.[56789] However, the question of whether we can satisfy this obligation remains unanswered.

The noted reduction in living standards among OA patients has caused a decline in their social lives.[101112] A national survey by arthritis care highlighted an inability to perform tasks of daily living among cases of poorly managed OA.[13] It is the second most common rheumatological problem, the most frequent joint disease with a prevalence of 22–39% in India[141516] and the most common cause of locomotor disability among the elderly causing morbidity and an economic burden on families and health care resources.[1718]

An understanding of the treating doctor's perception of pain relief among these patients is vital and detailed literature review failed to reveal any similar studies accounting for orthopedists’ views on pain management in OA. Being qualitative, this study poses no potential risk to any individual and its outcome mirrors its benefit, i.e., to stimulate orthopedists to provide optimum pain relief for OA patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

Study methods were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board (Ref No. 19/2013), and all doctors gave written informed consent to participate in the study. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and they could withdraw at any time without prejudice. No honorarium was paid and transcripts were kept confidential with restricted access.

Setting

The study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital located in South India.

Design

A qualitative design using a guide-based interview was employed according to guidelines for inductive qualitative research.[1920]

Participants

The sample comprised 15 qualified orthopedic surgeons from a tertiary care hospital in South India. The convenience method of sampling was adopted. Interviews continued till data saturation[2122] and sample size was determined accordingly.

Procedure

After approaching and priming participants regarding the study, each provided their written informed consent and a convenient time was setup to conduct the interview. A single investigator conducted face-to-face, semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions using a guide developed by the authors. Participants were assured privacy, confidentiality, and ample freedom to express their views and the interview was audio-recorded simultaneously. The guide was pilot-tested over three interviews (not included in the study) after which new ideas were added and redundant items omitted. The average duration of each interview was 18 min and audio-recordings were manually transcribed verbatim by two investigators independently. Clarifications, questions, or wrong notions regarding the transcript were addressed during a later discussion with each participant. The primary interviewer was a medical resident without any managerial role or position of authority, thereby eliminating any pressure, scrutiny or intimidation that would otherwise be attributed to hierarchy. To that extent, we may consider him “independent and unbiased.”

Analysis of data

The two analysts completed the data analysis.

Data analysis was initiated manually by both analysts using an iterative and interpretative approach. An inductive approach using thematic analysis was employed wherein new ideas and themes were allowed to emerge without prejudice. Emerging themes, categories, and subcategories were identified and better understood after discussion and sharing of coding patterns. This led to a final coding template according to which the later dataset was coded and analyzed.

RESULTS

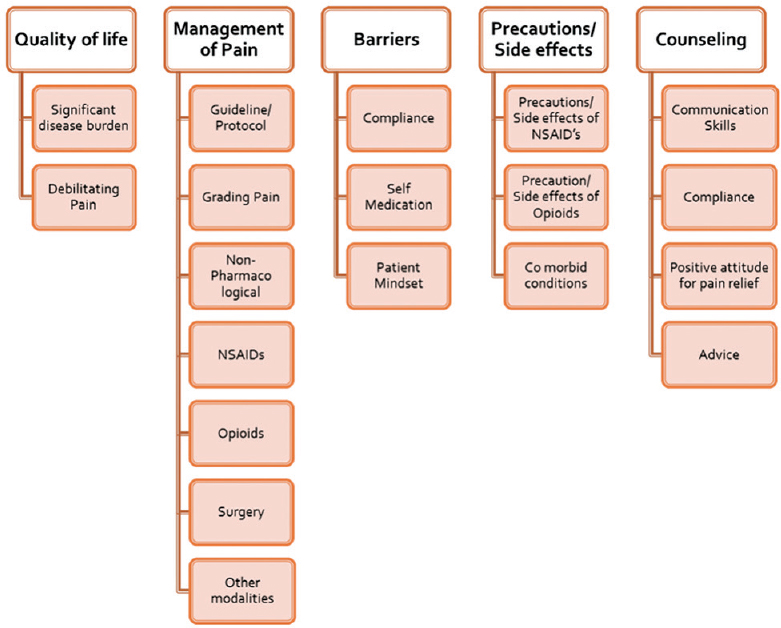

Five major themes emerged, namely, perspectives related to the quality of life, pain relieving modalities, side effects, barriers, and counseling. Subcategories identified under their respective themes are listed in Figure 1.

- Major themes and subcategories

Quality of life

Participants unanimously concurred that OA is associated with significant disease burden among Indians. This was attributed to the Indian lifestyle which entails sitting cross-legged, squatting to use the commode and various postures assumed during religious activities. All agreed that debilitating pain (usually involving the knee) caused decreased standard of living among patients.

“Pain is significant… sometimes they will start weeping and tell I cannot walk even a few metres, I cannot sleep at all.”

“Indians squat much more than the western population. That's the reason you find more of OA knee than OA hip in India.”

On a daily basis, 15–30% patients seeking medical attention from the orthopedic outpatient department present with symptoms suggestive of OA. Its degenerative nature led participants to question whether acquisition of the disease is inevitable.

“Medications prescribed mainly meant to slow down the process or stop the process, it will not reverse the process in anyway.”

“We can relate it to a car tire-when a car tire wears off which will happen eventually, what we do in the end is we change the tire.”

Pain management overview

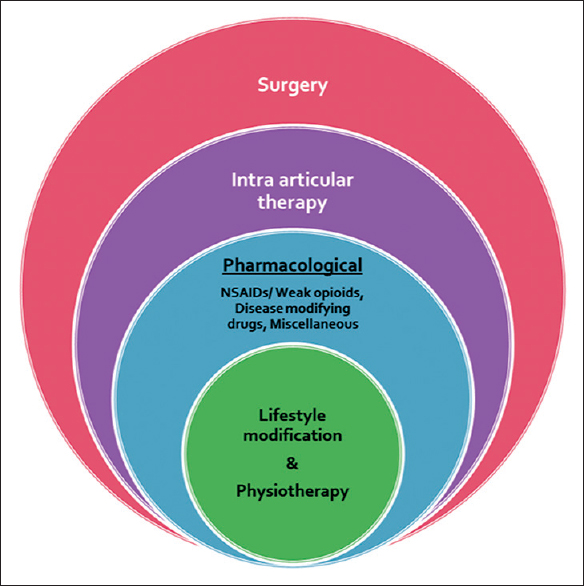

Based on participants’ views, OA requires “a multi-pronged method” of pain management. Figure 2 illustrates that at the core of this multifaceted scheme, lies the emphasis on physiotherapy and lifestyle modification. If adequate pain relief is not achieved, this can be coupled with a pharmacological modality which entails prescription of analgesics (usually paracetamol), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, or disease-modifying drugs (glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, diaserine).

- Pain management overview -multi-pronged method

Participants said that the evidence for using disease-modifying drugs, ayurvedic preparations and liniments was anecdotal and further research may prove their efficacy. Liniments satisfy the patient with temporary relief making it comparable to a placebo.

Although implantable devices have been adopted among their overseas counterparts, participants felt it is not warranted in most cases of primary OA. This is attributed to the expense suffered by patients along with maintenance and abuse liability.

If oral drug therapy fails to achieve adequate pain relief, one or two doses of intra-articular therapy using hyaluronic acid or steroid may be considered. Majority found intra-articular hyaluronic acid to be a short-term solution and suggested further studies be done to prove its long-term potential.

If all else fails, participants recommend surgery as a definitive solution, provided the patient is motivated. However, most patients tend to be highly reluctant for surgery.

“Definitely surgery is a better option for chronic, severe, symptomatic osteoarthritis.”

“If nothing works then surgery works.”

An often neglected aspect of pain management is its quantitative assessment. Although participants were aware of the visual analogue scale in their clinics, they admitted to not using it. They preferred to grade pain based on clinical, functional, and radiological assessment with rest-pain being its most severe form.

“We usually do not quantitatively assess the patient's pain which is a major drawback especially in the OPD. Sometimes the patients’ pain tends to be downplayed by the treating consultant. Not because of the work load. It's just that, that aspect is commonly neglected.

Sometimes pain management is not tailored to each particular patient's degree of pain or requirement. Usually, it is commonly a blanket therapy.”

Two major contributing factors are the outpatient workload and the mind-set of patients who crave immediate pain relief, resulting in poor compliance to physiotherapy and lifestyle modification. Analgesics such as NSAIDs prescribed as short-term measures while providing immediate symptomatic relief tend to have high abuse liability due to their over-the-counter availability and the gross lack of awareness of their long-term side effects.

“We spend a very short time with the patients in the OPD. It's hardly 2–3 minutes, it's very hard to convince the patient to follow conservative measures because the patient already has a fixed mind-set and the patient has other problems such as finance etc., which we can’t usually deal with so more often than not we just prescribe so that the patient is satisfied and we send them.”

Guidelines versus no guidelines

Currently, no definitive protocol exists and most participants exercise individual discretion as against any guideline.

“We don’t have any protocol… follow the basic principles that we have been taught in our training and profession.”

“Osteoarthritis is not the same disease, deformities are not the same, symptoms are not the same, needs of a person are not the same. Therefore I prefer individually we should assess and then decide what the right course of treatment for that person is.”

However, a few felt the need to systematize pain management.

“Need to probably systematize our pain management methods and get a protocol on how we are going to start and how we are going to step up and how long we are going to continue.

A system of monitoring the patients, what drugs they are getting and looking out for the complications. We need to get those sorts of guidelines here but more importantly monitor them.”

Precautions/side effects of pharmacotherapy

Paracetamol and NSAIDs are often prescribed for short-term pain relief due to their few side effects (gastritis and constipation at high doses). Many participants felt that long-term drug therapy could lead to habituation and ignorance of the underlying disease. While some preferred a paracetamol-opiod combination or the weak opioid alone, others were sceptical of using opioids altogether.

“I’m totally against tramadol and its products… most patients come back with giddiness and vomiting. You are treating one illness and you giving him another illness.”

“Found some people do tend to lose their neurological faculties and become confused after taking a mild dose of tramadol… long term side effects are also there.”

Patients’ age and comorbidities (renal disease, diabetes, hypertension, etc.) also influenced doctors’ prescribing patterns.

Role of counseling

Participants agreed that counseling could motivate patients to overcome their pain. A question asked was “Your opinion on the following- ‘Patients who have an understanding of the disease and its natural history cope better and report less pain.’ The important goal is to instil a positive attitude.” Participants concurred that this statement holds true in clinical practice as the two-way process allows patients to understand their condition and cope accordingly. Patients’ confidence in their practitioner's interpersonal skills, communication skills, and holistic approach toward treatment helps in achieving better results. Some pointed out limitations of counseling-like the patient's constant demand for immediate pain relief.

“Idea of instilling a positive attitude is good but if the patient has pain day in and day out then I don’t know how effective counseling is.”

“Once again it depends on the class of patients that come to us. The educated class is easier to explain, they definitely will do those things. If there is a poor patient who has no money to buy a western commode then I can’t tell them him not to squat.”

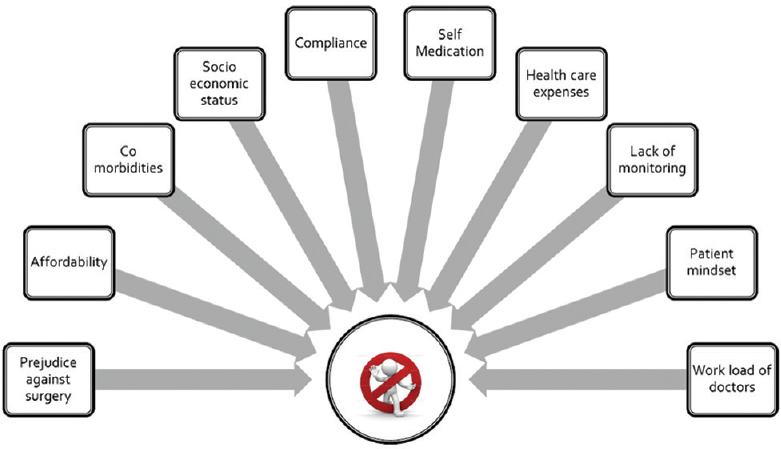

Barriers in pain management

Barriers to optimal pain management explained by participants are listed in Figure 3. As patients expect immediate solutions for their pain, it is difficult to motivate compliance in areas of physiotherapy and lifestyle modification. On being prescribed certain drugs, patients tend to self-medicate to achieve rapid symptomatic relief. There also lacks a system of follow-up due to low finances and the time expenditure suffered by the patient.

- Barriers to optimal pain management in osteoarthritis

“Patient will usually come for immediate pain relief so if you suggest something else like physiotherapy then they will be unwilling to accept it.”

“Barriers would be loss to follow-up. You start some molecules; final follow-up is very difficult in our setup.”

“Cumbersomeness of travelling to the hospital and expenses related to visiting the doctor.”

“I don’t think we have the time to counsel… seeing 60–70 patients in the OPD in 3 hour, I think it's not possible.”

“Tend to self-medicate with pain killers.”

DISCUSSION

Orthopedists working in a tertiary care hospital shared with us their experiences while managing pain in OA. The significance of this study stems from the fact that OA is associated with chronic debilitating pain causing impairment. The number of persons diagnosed with obesity has increased drastically, giving rise to a large population of susceptible individuals who are predisposed to this increased disease burden. While few studies have been carried out in the U.K and Europe regarding patient-physician perspectives on changes in quality of life due to OA, none has delved into doctors’ views on pain management of the same.

Pain associated with OA requires various forms of treatment to achieve adequate relief.[23] In the UK, the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA) have developed standards for people with OA (ARMA 2004). These stipulate that people have the right to access appropriate services; timely diagnosis and treatment; information; patient-centered services; independence; and self-determination. The contrasting scenario in India presents a delay in seeking allopathic treatment after the onset of symptom possibly due to the shortage of orthopedic specialists and primary health-care physicians, especially in rural India.

Campbell et al. suggested two principal dimensions for quality of care of patients, its accessibility and effectiveness. They further elaborated that the extent of help provided depends on practitioners’ knowledge and availability of resources.[24] In India, patients often choose to ignore their pain and permit its progression or resort to traditional bone setters or healers (nonmedical persons acquiring skills through family training or apprenticeship) for relief, often leading to complications. People lack awareness of the living aids or home adaptations available. Campbell et al. also observed that high-quality care cannot be achieved without actively involving patients. Previous studies on chronic osteo-articular disease revealed that practitioners’ views often differ from patients’ views and the perception of patients’ expectations by practitioners differ from those implied by patients.[252627]

Spontaneously, practitioners express little concerning OA management. Nevertheless, probing and analysis of interviews exposed perspectives concerning treatment, outcome measures, prevention, surgical intervention, and scope for further research. Although participants did not express their feelings toward the limitation faced in treating pain, they made it a point to emphasize the need for structured treatment to decrease or halt OA evolution and medications with fewer side effects and broader therapeutic options. While studies have shown a weak opioid and paracetamol combination to be efficacious in relieving OA pain,[28293031] some participants expressed concern regarding their long-term adversities.

A multi-centric study done in Europe observed that practitioners’ representations of management steps are schematic and based on flare-up treatments. The first step consists of symptomatic pharmacological management by general practitioners; the second of joint injections (mainly corticoids) by a knee specialist (rheumatologist in France); and the third step is joint replacement by an orthopedic surgeon.[32] The American Orthopaedics Association and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence have prepared guidelines for appropriate treatment of OA in America and the national health services (NHS) (England and Wales), respectively. Similar such guidelines exist in Sweden and Australia.

Indian doctors have reserved opinions about existing assessment tools and guidelines and question their feasibility in the contrasting health-care infrastructure. Despite general scepticism, some do feel that pain management needs to be systematized – if not a definitive protocol, a set of well-framed departmental guidelines would aid in better management of OA. A special clinic to provide better care to patients with OA was also suggested.

Doctors emphasized that preventive measures and early detection could lead to better management of OA, by reducing concurrent complications.

The limitations of this study are that it is a single-center study, and the varying perspectives of each are not universal. There exists a need to correlate doctors’ perspectives with those of their patients as well as a need to factor in the feelings of the clinician with regard to certain constraints in treatment of pain. It may also be beneficial to extend this study to rheumatologists.

CONCLUSION

Orthopedic surgeons agree that OA entails a disease burden associated with debilitating pain impairing activities of daily living. The general opinion is that pain management needs to be optimal for improving the quality of life among these patients and that counseling plays a major role apart from medications. Unfortunately, due to the overwhelming outpatient load, this is often compromised. A multi-disciplinary team approach in this context might be beneficial. There is also a need to correlate doctors’ perspectives with those of their patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Phaneesha M. S., Head, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Dr. S. D. Tarey, Head, Department of Palliative Medicine and Dr. George D’Souza, Medical Superintendent, St. John's Medical College Hospital for administrative support.

REFERENCES

- Musculoskeletal Clinical Metrology. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993.

- OPCS Surveys of Disability in Great Britain. Report 1. In: The Prevalence of Disability among Adults. London: HMSO; 1988.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tramadol/paracetamol fixed-dose combination in the treatment of moderate to severe pain. J Pain Res. 2012;5:327-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recognizing pain management as a human right: A first step. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:8-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethics, law, and pain management as a patient right. Pain Physician. 2009;12:499-506.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of care for people with osteoarthritis: A qualitative study. J Nurs Healthc Chronic Illn. 2006;7b:168-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pattern of health care utilisation of elderly people with arthritic pain in the hip or knee. I J Qual Health Care. 1997;9:129-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, Illinois: Aldine Publications; 1967.

- Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Qualitative sociology. 1990;13:1.

- [Google Scholar]

- TNS Health Care and Arthritis Care. In: Arthritis Care Survey. Arthritis Care. 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Bhigwan (India) COPCORD: Methodology and first information report. APLAR J Rheumatol. 1997;1:145-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO-ILAR COPCORD Study. WHO International League of Associations from Rheumatology Community Oriented Program from Control of Rheumatic Diseases. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in a rural population in western India: A WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:240-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aging, articular cartilage chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis. Biogerontology. 2002;3:257-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economics of osteoarthritis: A global perspective. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1997;11:817-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life in patients waiting for major joint replacement. A comparison between patients and population controls. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health status in patients awaiting hip replacement for osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41:1001-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative Data Analysis (2nd ed). London: Sage Publications; 1994.

- Research Methods in Health. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997.

- Clinical Standards Advisory Group issues its final reports. British Med. 2000;320:1026.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of chronic diseases on the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of Chinese patients in primary care. Fam Pract. 2000;17:159-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Personal impact of disability in osteoarthritis: Patient, professional and public values. Musculoskeletal Care. 2006;4:152-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Values for function in rheumatoid arthritis: Patients, professionals, and public. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:928-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tramadol in musculoskeletal pain – A survey. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21(Suppl 1):S9-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- CAPSS-105 Study Group. Tramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis flare in an elderly patient population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:374-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patients’ and practitioners’ views of knee osteoarthritis and its management: A qualitative interview study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19634.

- [Google Scholar]