Translate this page into:

Setting-up a Supportive and Palliative Care Service for Children with Life-threatening Illnesses in Maharashtra – Children’s Palliative Care Project in India

*Corresponding author: Mary Ann Muckaden, Department of Palliative Medicine, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. muckadenma@tmc.gov.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Muckaden MA, Ghoshal A, Talawadekar P, Marston JM, Paleri AK. Setting-up a supportive and palliative care service for children with life-threatening illnesses in Maharashtra – children’s palliative care project in India. Indian J Palliat Care 2022;28:236-49.

Abstract

Objectives:

To describe the key initiatives that were successful in planning and implementing hospital- and community-based Paediatric Palliative Care (PPC) services designed for a resource-limited setting in Maharashtra, India, in collaboration with DfID.

Materials and Methods:

The CPC project was a 5-year service development project (April 2010–March 2015) conducted in Maharashtra, India, developed in collaboration with the Department for International Development (DFID), Hospice UK, International Children’s Palliative Care Network (ICPCN), Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) and Tata Memorial Centre, to advocate and care for the needs of children and families with life-limiting illnesses in a non-cancer setting. It was implemented through raising awareness and sensitising hospital administrators and staff about PPC, providing education and training on PPC, team building, and data collection to understand the need for PPC.

Results:

The total number of children enrolled in the CPC project was 866, 525 (60.6%) were male with a mean age of 9.3 years. Major symptom across sites was mild pain, and serial Quality of Life measurement (through PedsQL questionnaire) showed improvement in social, psychological and school performance. Advocacy with the Ministry of Health helped in procurement of NDPS licenses in district hospitals, and led to access to palliative care for children at policy level.

Conclusion:

The model of PPC service development can be replicated in other resource-limited settings to include children with life-limiting conditions. The development of pilot programmes can generate interest among local physicians to become trained in PPC and can be used to advocate for the palliative care needs of children.

Keywords

Palliative care

Children’s health

Developing world

Health services research

INTRODUCTION

The focus of care for children with life-limiting conditions has traditionally been limited to investigation, diagnosis, treatment and an attempt to cure.[1] More recently, there has been increased incorporation of comprehensive palliative and supportive care into routine care not only for these children but also for their families, as well. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the Association for Children’s Palliative Care (CPC), and the World Health Organization have proposed the use of an integrated model of palliative and curative care, for children and families, from the time of diagnosis throughout the illness trajectory to allow the child and family to benefit maximally from both philosophies of care simultaneously.[2-5] Although paediatric palliative care services are relatively well developed in Western world, the development of palliative care services for children in India is in its infancy.[6] At the time of conceptualising this study, there were a few centres dedicated to CPC and most of them for cancer. Further, there was disparity between the delivery of such services between urban and rural India, where part of this study was undertaken.[7]

The CPC project was a 5-year project (April 2010–March 2015) conducted in Maharashtra, India, developed in collaboration with the Department for International Development (DFID), Hospice UK, International Children’s Palliative Care Network (ICPCN), Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) and Tata Memorial Centre, to advocate and care for the needs of children and families with life-limiting illnesses,[7] in a non-cancer setting. The project envisaged working alongside stakeholders at the level of the Government of Maharashtra and experts in the field of CPC. The experiences gained would act as a nidus to set up many more such centres in India.

Aim

The aim of the study was to develop a sustainable model of paediatric palliative care to respond to the suffering and unique needs of children and their families, with life-limiting conditions, with the aim to improve their quality of life (QoL).

Objectives

The objectives of the study are as follows:

Develop centres of excellence for the delivery of paediatric palliative care in liaison with the Government of Maharashtra and use them as tools for advocacy for the rest of India

Develop availability of essential analgesics such as morphine

Development of models of education and training of healthcare professionals, volunteers and community organisations

Empowerment of these children and their families and developing strategies to improve their QoL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

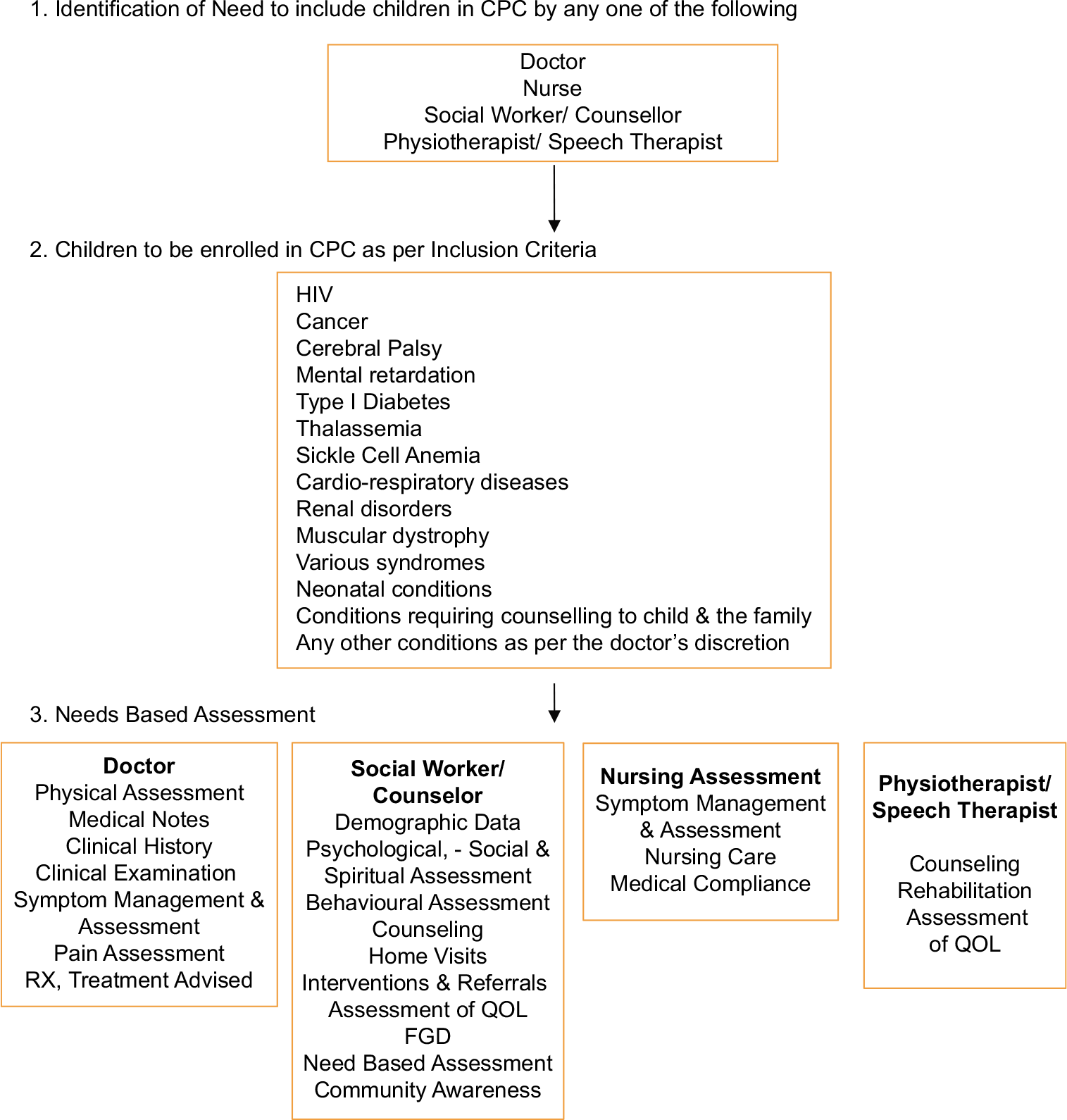

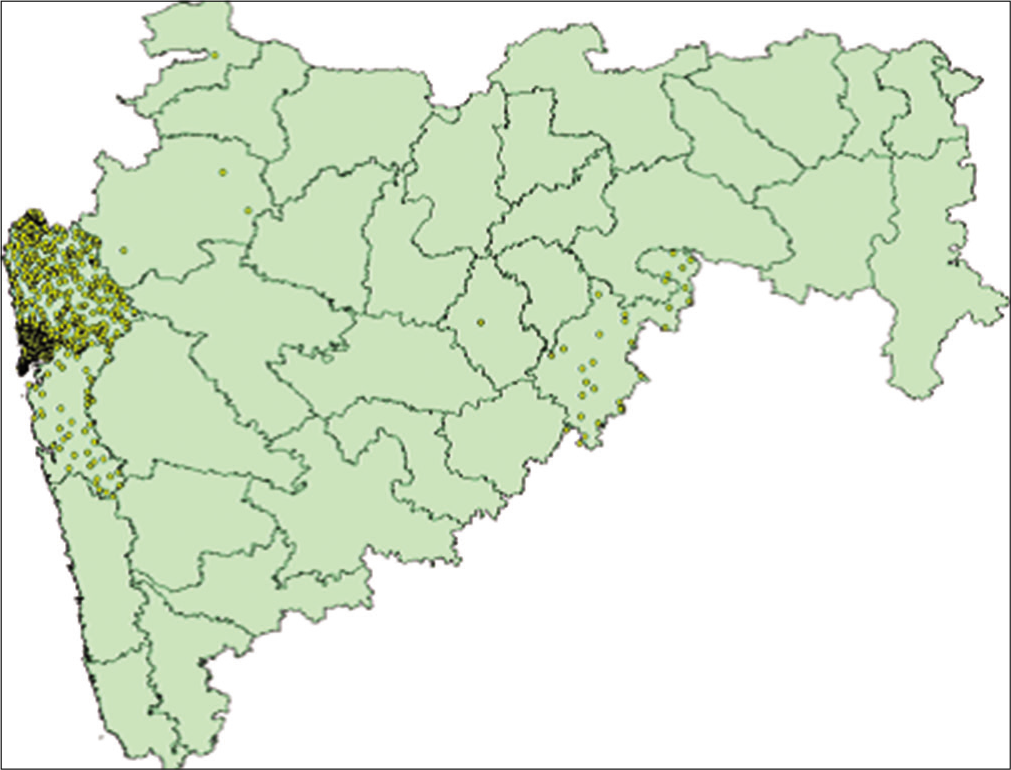

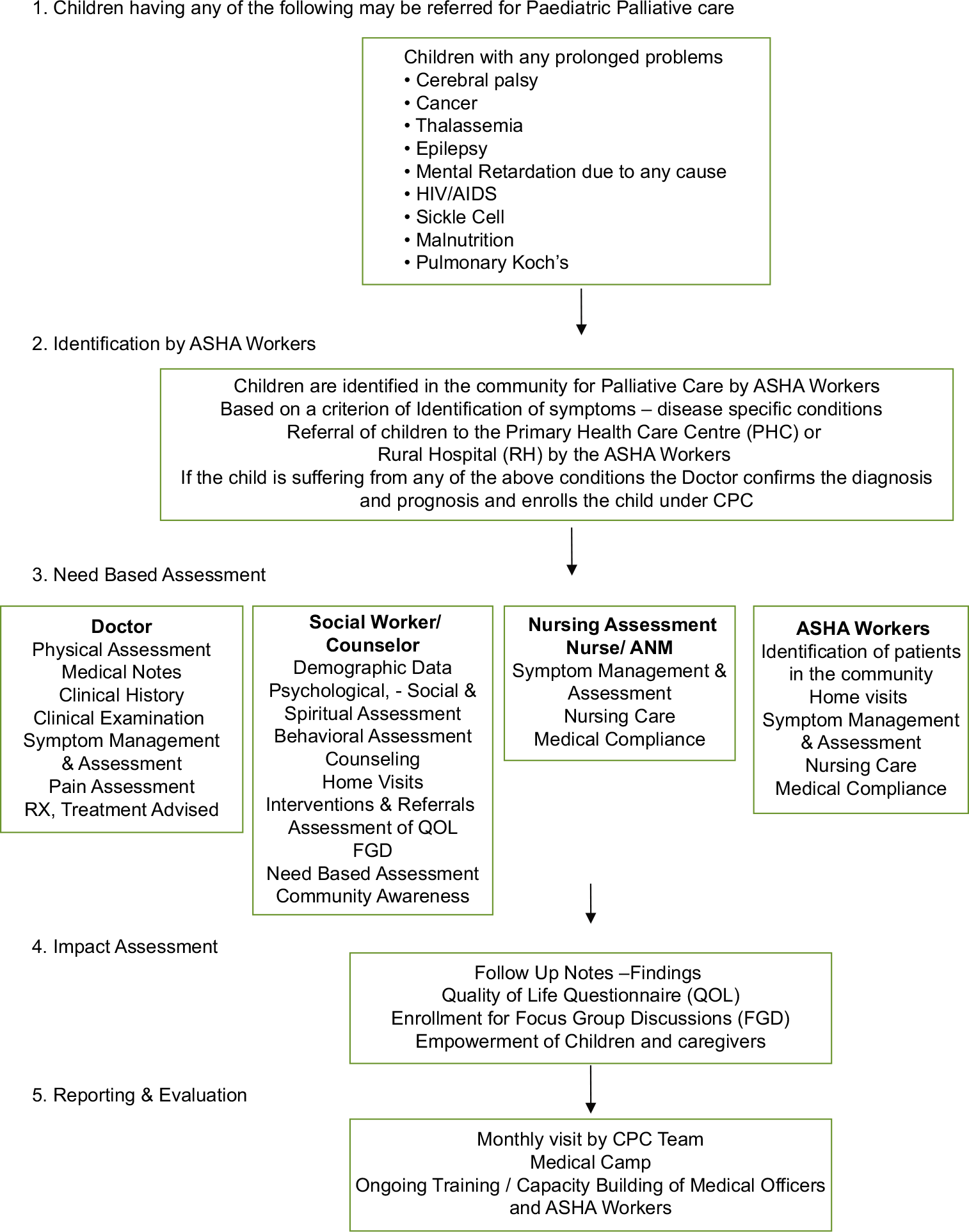

The project was designed to develop palliative care in three facilities having already well-developed paediatric healthcare services [Figure 1]. A detailed methodology with timelines was planned at the beginning of the project [Figure 2]; each site was then developed in turn, as per the objectives. The model centre at Patangshah Cottage Sub District Hospital, Jawhar (Rural site), started from February 2011 in association with Maharashtra National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). Children who were already attending the paediatric outpatients were enrolled. The most of the beneficiaries were children with neurological conditions and severe malnutrition. The next centre was started in August 2011 in collaboration with the Department of Paediatrics, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital and Medical College, Sion (Urban site). Children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome were recruited from this centre. The last centre was started in January 2013 in association with Mahatma Gandhi Mission Hospital, Kalamboli, a combination of urban and rural populations. Children with various life-limiting conditions that is, thalassemia, cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophy were enrolled under the project.

- Geographical distribution of children’s palliative care clients in the state of Maharashtra.

- Step-wise approach for the methodology adopted.

Project activities

Case record forms were created by holding meetings with taskforce members and experts from the three project sites. Data were collected and collated by key programme developers, which included demographic and clinical data at presentation and for every follow-up, physical or telephonically. All interventions were recorded and assessed at taskforce meetings. Efforts to ensure morphine availability and its use at every site were recorded and regularly followed up. Reasons for non-availability were reviewed and pragmatic solutions were charted. Data on QoL were collected using Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Measurement Model.[8] Focus group discussions were held with parents in cases where PedsQL was not feasible. Interview notes were transcribed by a researcher; content analysis was done and open coding was used to identify common themes.[9] Descriptive statistics were used to summarise all data. Regular trainings for all cadres of healthcare workers involved in the project were conducted, and regular assessments of all elements of the project were done by members of the taskforce to audit the real-time development versus projected timelines. Wherever not achieved, reasons were documented and adjustments to targets were made.

Coordination and timeline compliance

The project was coordinated by the CPC team led by a Project Coordinator with mentorship by Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH) and IAPC, along with data managers. The coordinator arranged for trainings, empowerment activities, and site monitoring. The scheduling was planned in consultation with partners during stakeholder meetings and site visits through a logical framework. Regular team meetings were arranged to monitor for timeline compliance. We followed a mixed-method approach where quantitative data analyses were done with SPSS software and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant,[10] and for qualitative data, we followed thematic content analyses as suggested by Clarke and Braun.[11] The data were stored securely and unanimously by the project investigators in accordance with institutional data protection policies. This was a service project and permission was granted through a memorandum of understanding between the TMH, NRHM, Maharashtra, and the IAPC details in [Appendices 1-3].

RESULTS

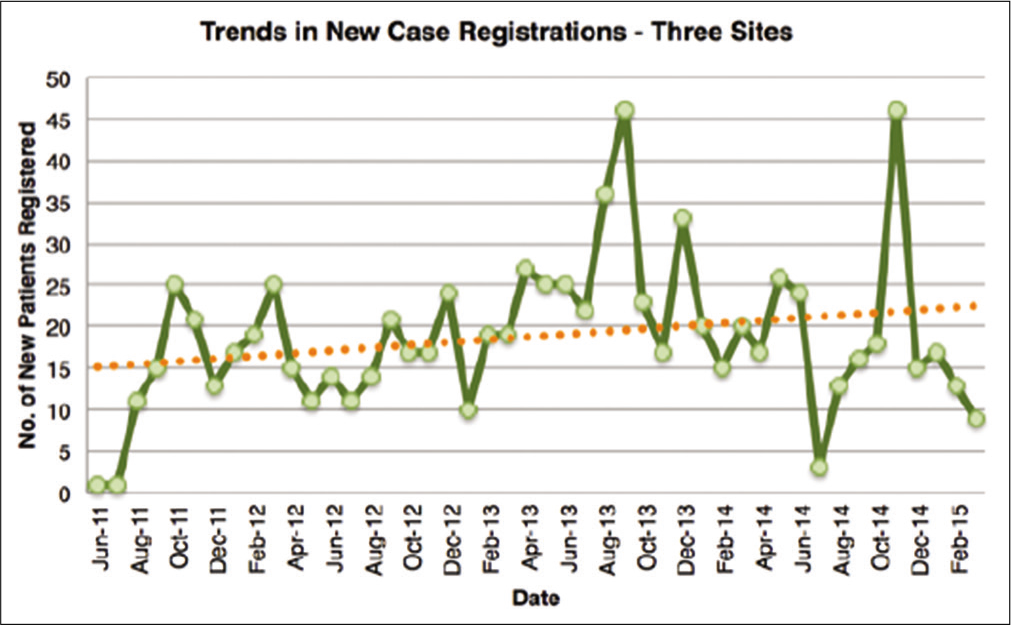

The results of the first two objectives will be presented in this paper, as the results from the third objective have been described in a separate paper.[7] New Case Record Form was developed for the 1st time in India for CPC in non-cancer conditions. With some minor adjustments to expected targets, the project demonstrated good results. The total number of children enrolled in the CPC project across three sites was 866 [Figure 3].

- Recruitment trends in new cases.

Demographic profile

Mean age was 9.3 years (average age of children enrolled in Sion Hospital was 11 years, Jawhar Hospital was 9 years and 6 years in Kalamboli Hospital), 525 (60.6%) were male (217 [58%] at Sion Hospital, 216 [61%] in Jawhar Hospital and 92 [68%] in Kalamboli Hospital). Even though children were affected with life-limiting conditions in all sites, 499 (57.6%) of them attended regular schools or CANSHALA[12] (special school for children with cancer), with an average dropout rate of 106 (12.2%). The most of the children enrolled for the CPC services in urban and rural settings belonged to the low-income group 687 (79%). The documented primary caregiver was the mother in 489 cases (56.5%) [Table 1].

| Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital and Medical College, Sion, n(%) | Patangshah Cottage Sub District Hospital, Jawhar, n(%) | Mahatma Gandhi Mission Hospital, Kalamboli, n(%) | Total,[1]n(%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 160 (42) | 138 (39) | 43 (32) | 341 (39.4) | ||

| Male | 217 (58) | 216 (61) | 92 (68) | 525 (60.6) | ||

| Age | ||||||

| ≤5 years | 42 (11) | 95 (27) | 69 (51) | 206 (23.8) | ||

| 6–10 years | 81 (21) | 76 (21) | 42 (31) | 199 (22.9) | ||

| 11–12 years | 138 (37) | 105 (30) | 13 (10) | 256 (29.6) | ||

| >12 years | 116 (31) | 78 (22) | 11 (8) | 205 (23.7) | ||

| Patient status | ||||||

| New | 14 (4) | 0 (0) | 13 (10) | 27 (3.1) | ||

| Follow-up | 327 (87) | 343 (97) | 121 (90) | 791 (91.3) | ||

| Died | 10 (3) | 10 (3) | 1 (1) | 21 (2.4) | ||

| Lost to follow-up | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Transfer to other centres | 16 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (1.8) | ||

| Transfer to adult medicine | 9 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (1.0) | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| AIDS | 377 (100) | 6 (1.7) | 3 (2.2) | |||

| Neurological conditions | 0 (0) | 125 (35.3) | 38 (28.1) | |||

| Cardiovascular conditions | 0 (0) | 26 (7.3) | 15 (11.1) | |||

| Thalassemia | 0 (0) | 12 (3.4) | 17 (12.6) | |||

| Pulmonary Koch’s | 0 (0) | 13 (3.7) | 3 (2.2) | |||

| Neonatal conditions | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (3.7) | |||

| Down syndrome | 0 (0) | 9 (2.5) | 8 (5.9) | |||

| Juvenile diabetes | 0 (0) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (4.4) | |||

| Tuberculous meningitis | 0 (0) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Cancer | 0 (0) | 6 (1.7) | 0 (0) | |||

| Congenital anomalies | 0 (0) | 11 (3.1) | 8 (5.9) | |||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Respiratory conditions | 0 (0) | 14 (3.9) | 10 (7.4) | |||

| Leprosy | 0 (0) | 11 (3.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Rheumatic heart disease | 0 (0) | 12 (3.4) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Muscular dystrophy | 0 (0) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Severe malnutrition | 0 (0) | 34 (9.6) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Nephrotic syndrome | 0 (0) | 5 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Sickle cell anaemia | 0 (0) | 21 (5.9) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Various disabilities | 0 (0) | 34 (9.6) | 0 (0) | |||

| Neurodegenerative conditions | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Biliary atresia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Haemophilia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Guillain–Barré syndrome | 0 (0) | 6 (1.7) | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Education | ||||||

| Regular | 251 (67) | 193 (55) | 55 (41) | 499 (57.6) | ||

| Dropout | 52 (14) | 49 (14) | 5 (4) | 106 (12.2) | ||

| Irregular | 35 (9) | 33 (9) | 6 (4) | 74 (8.5) | ||

| Informal schooling | 39 (10) | 79 (22) | 69 (51) | 187 (21.6) | ||

| Medicine adherence | ||||||

| Good | 343 (93) | 252 (71) | 102 (76) | 697 (80.5) | ||

| Fair | 25 (7) | 82 (23) | 28 (21) | 135 (15.36) | ||

| Poor | 2 (1) | 19 (5) | 5 (4) | 26 (3) | ||

| Primary caregiver | ||||||

| Mother | 193 (53) | 202 (57) | 94 (70) | 489 (56.5) | ||

| Father | 32 (9) | 75 (21) | 32 (24) | 139 (16) | ||

| Grandparents | 68 (19) | 55 (16) | 6 (4) | 129 (14.9) | ||

| Brother | 19 (5) | 13 (4) | 1 (1) | 33 (3.8) | ||

| Aunty/uncle | 32 (9) | 7 (2) | 1 (1) | 40 (4.6) | ||

| NGO/institution | 7 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 8 (0.9) | ||

| Parents (both) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.6) | ||

| Others | 10 (3) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 12 (1.4) | ||

| Family income | ||||||

| Low | 327 (48) | 294 (43) | 66 (10) | 687 (79) | ||

| Middle | 39 (24) | 56 (35) | 65 (41) | 160 (18) | ||

| NA | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) | 6 (1) | ||

| High | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 3 (0.3) | ||

| General examination | ||||||

| Good | 224 (60) | 213 (60) | 13 (10) | 450 (51.9) | ||

| Fair | 150 (40) | 125 (35) | 101 (75) | 376 (43.4) | ||

| Poor | 2 (1) | 16 (5) | 21 (16) | 39 (4.5) | ||

| Intervention | ||||||

| Counselling | 306 (82) | 229 (65) | 78 (58) | 613 (70.8) | ||

| Nutritional | 21 (6) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 28 (3.2) | ||

| Telephonic follow-up | 25 (7) | 16 (5) | 37 (27) | 78 (9) | ||

| Non-governmental organisation | 10 (3) | 11 (3) | 7 (5) | 28 (3.2) | ||

| Medical | 9 (2) | 12 (3) | 9 (7) | 30 (3.5) | ||

| Educational | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (0.6) | ||

| Physiotherapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Orphanage | 0 (0) | 13 (4) | 0 (0) | 13 (1.5) | ||

| Home-based care | 1 (0) | 59 (17) | 0 (0) | 60 (6.9) | ||

| Vocational guidance | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.5) | ||

| Focus group discussion | ||||||

| Yes | 197 (54) | 102 (29) | 8 (6) | 307 (35.4) | ||

| No | 167 (46) | 252 (71) | 127 (94) | 546 (63) | ||

| Total | 377 (43.5) | 354 (40.9) | 135 (15.6) | 866 | ||

AIDS: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Clinical profile

On average, 450 (51.9%) had good general condition (224 [60] at Sion Hospital, 213 [60] in Jawhar Hospital and 13 [10] in Kalamboli Hospital). The pain was the most common symptom encountered among the enrolled children – in Sion Hospital, 5% of children had pain score of 6/10, in Jawhar Hospital, 5% of children have pain score above 4/10 and in Kalamboli Hospital, 19% of children had a pain score up to 3/10. The majority of the pain could be taken care of by Step I analgesics. At each site, key interventions were symptom management and counselling, medical, nutritional, educational and vocational guidance. Children were also referred to special referral services where possible for example, 41 (11%) of children in Sion to the psychiatric unit for counselling and 16 (12%) of children from Kalamboli were referred for physiotherapy for cerebral palsy. Other specialty referral services included referrals to orthopaedics, neurology and ophthalmology. Jawhar Hospital had done 60 (17%) of home visits and Kalamboli Hospital had 36 (27%) of phone follow-up. Networking and referral to NGO were made for 121 (32%) in Sion and 74 (21%) in Jawhar, respectively. The impact of interventions was measured by administering the PedsQL questionnaire.

Home visits

Efforts were made to identify issues such as child abuse and domestic violence during home visits. Continuum of care was assured through ward visits and ‘Open door policy’ for children transferred to adult services.

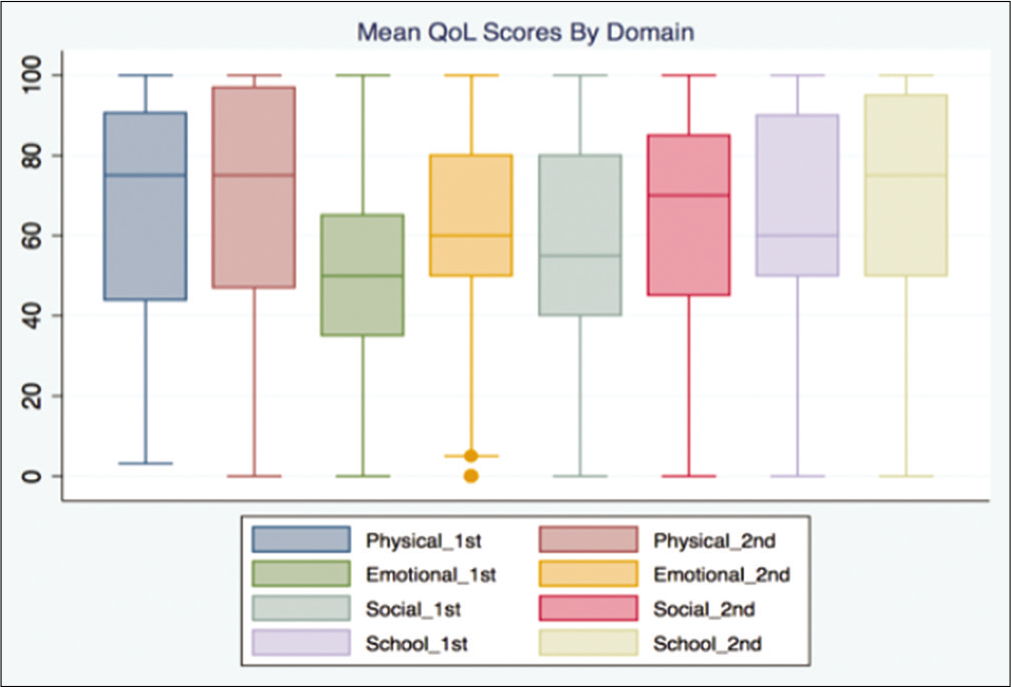

Paediatric QoL

The improvement in QoL was measured by filling PedsQL questionnaire at the interval of 3 months. It was seen that though there was not much improvement in the physical functioning, there was a statistically significant improvement in social, psychological and school performance [Table 2].

| Items | Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital and Medical College, Sion (%) | Patangshah Cottage Sub District Hospital, Jawhar (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | |||||

| Physical functioning | ||||||||

| Walking more than 1 block | 50 | 75 | 61 | 58 | ||||

| Running | 50 | 72 | 45 | 58 | ||||

| Participating in sports activity or exercise | 53 | 78 | 68 | 81 | ||||

| Lifting something heavy | 54 | 75 | 66 | 78 | ||||

| Taking a bath or shower by him or herself | 62 | 84 | 71 | 81 | ||||

| Doing chores around the house | 46 | 77 | 52 | 83 | ||||

| Having hurts or aches | 46 | 71 | 52 | 63 | ||||

| Low-energy level | 41 | 66 | 47 | 53 | ||||

| Emotional functioning | ||||||||

| Feeling afraid or scared | 21 | 58 | 22 | 44 | ||||

| Feeling sad or blue | 20 | 58 | 23 | 47 | ||||

| Feeling angry | 19 | 64 | 23 | 60 | ||||

| Trouble sleeping | 34 | 66 | 47 | 70 | ||||

| Worrying about what will happened to him or her | 29 | 66 | 40 | 74 | ||||

| Social functioning | ||||||||

| Getting along with other children | 42 | 71 | 51 | 64 | ||||

| Other kids not wanting to be his or her friend | 40 | 69 | 48 | 70 | ||||

| Getting teased by other children | 39 | 74 | 52 | 75 | ||||

| Not able to be doing things that other children of his or her age can do | 35 | 69 | 48 | 61 | ||||

| Keeping up when playing with other children | 34 | 69 | 47 | 77 | ||||

| School functioning | ||||||||

| Paying attention in class | 42 | 67 | 48 | 66 | ||||

| Forgetting things | 43 | 68 | 44 | 61 | ||||

| Keeping up with schoolwork | 42 | 67 | 41 | 62 | ||||

| Missing school because of not feeling well | 58 | 85 | 56 | 84 | ||||

| Missing school to go to other doctor or hospital | 52 | 79 | 56 | 80 | ||||

| Differences in summary scores of PedsQL | Paired differences | Std. deviation | 95% confidence interval of the difference | t | df | p value (2-tailed) | ||

| Mean | Std. error mean | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital and Medical College, Sion | 29.4 | 6.3 | 1.4 | 26.6 | 32.1 | 22.478 | 22 | <0.001 |

| Patangshah Cottage Sub District Hospital, Jawhar | 19.2 | 9.5 | 1.9 | 15.1 | 23.3 | 9.724 | 22 | <0.001 |

Paediatric quality of life inventory

Morphine availability

Although there were some challenges in getting morphine license for urban project sites, the rural site got the license, and they were prescribing morphine for pain management. With advocacy with the Ministry of Health, Maharashtra State, 17 other district hospitals also got NDPS licenses in 2015.

Status at last follow-up (March 2015)

Over a period of 5 years, 736 (85%) of the children in all three sites were followed up with the CPC project. The number of deaths was 11 (3%) in Sion, 11 (3%) in Jawhar and 1 (1%) in Kalamboli Hospitals.

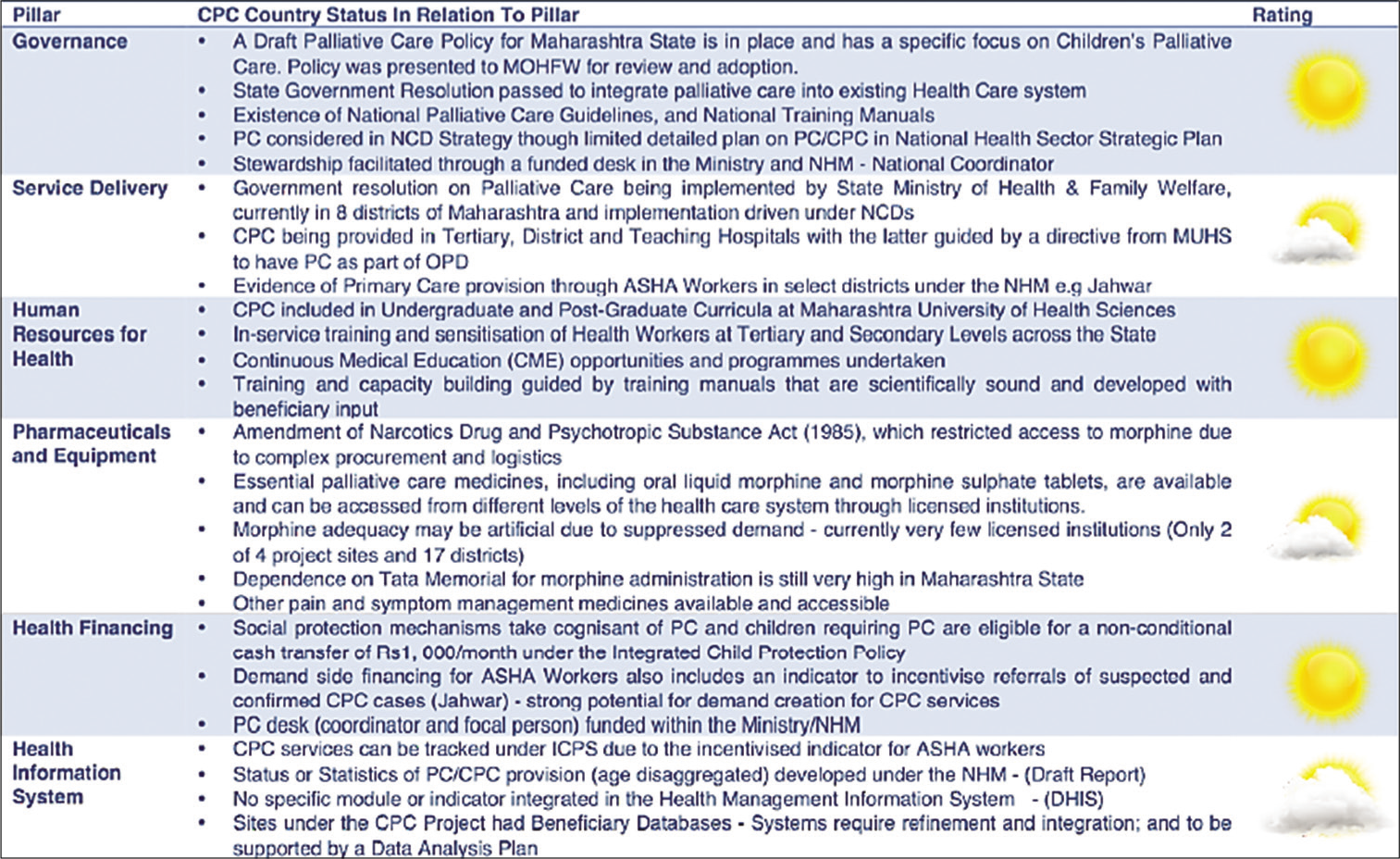

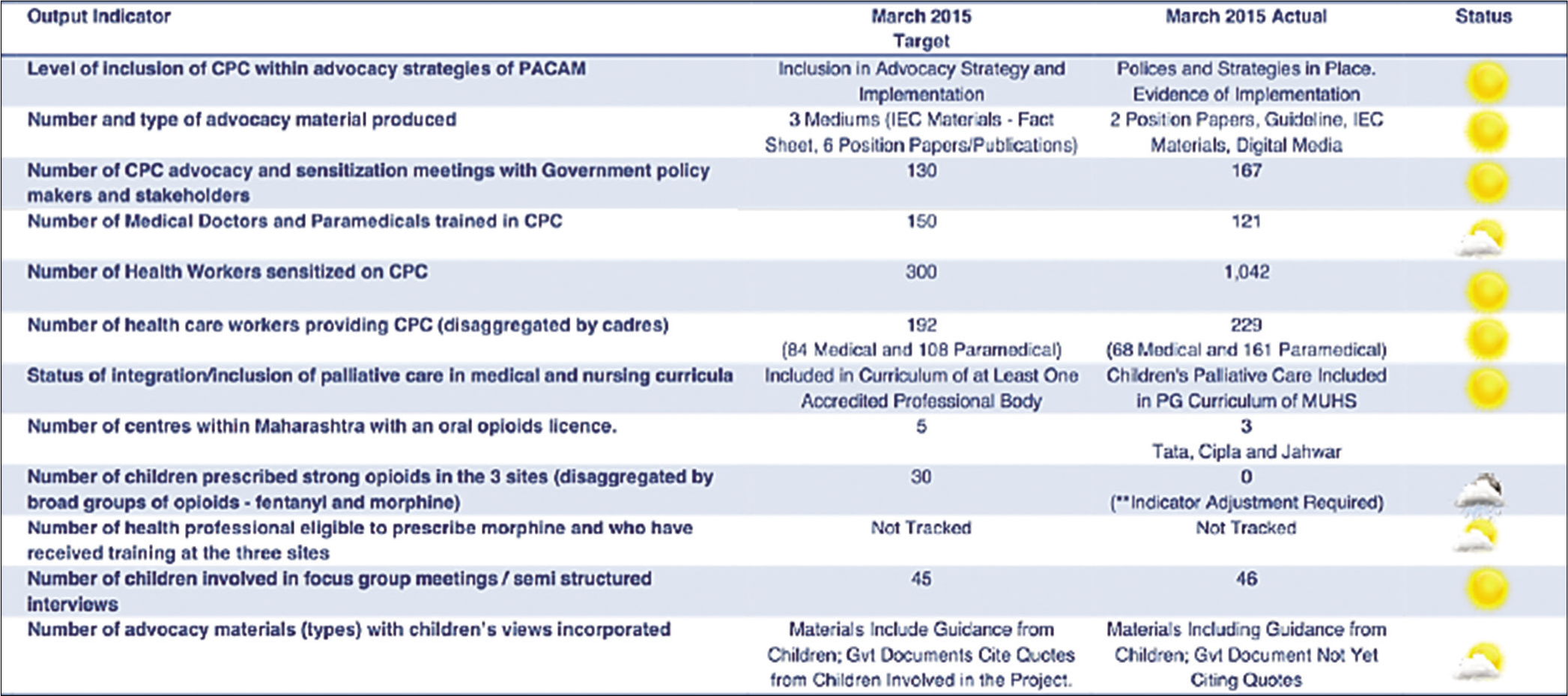

Advocacy

The core set of activities were undertaken successfully as planned and in line with the project’s design [Figure 4]. The project impact led to increased access to palliative care for children as well as to changes in Maharashtra’s healthcare policy. Key developments were the establishment of CPC services at the three new sites, two of which still serve as training sites, improvements in health worker knowledge on CPC as well as increased community awareness of CPC.[7] There was good output target compliance as shown in [Figure 5]. Maharashtra Palliative Care Policy was passed on 15 June 2013 by the Government of Maharashtra for the implementation of palliative care in Maharashtra[13] and was included in the non-communicable diseases programme of the state.[14] A project implementation plan was formed in collaboration with the National Health Mission since 2011 for implementing palliative care in different districts of Maharashtra. Palliative care has been implemented in Jawhar and Igatpuri Cottage Rural Hospital. Advocacy meetings were held both at state and central level with various stakeholders to facilitate the inclusion of CPC; capacity building of various health cadres and the implementation and delivery of CPC in various healthcare settings urban, peri-urban and rural. The continuation of the project focused on policymaking for state (this would influence centre – set pattern in India), capacity building (medical training), and availability of essential narcotic drugs; conforming to the WHO recommended public health model for national PC delivery. Integrated Child Protection Scheme (ICPS) for children and families suffering with a life-limiting illness was approved by the Ministry of Women and Child Development on 27 December 2013 for sponsorship of INR 2000 ($ 27). The Tata Memorial Centre implemented the Child Protection Policy for safeguarding the rights of children availing care in hospital settings in 2012. The same was implemented at Sion Hospital. Media outreach included – Beautiful Life Project (English and Marathi leaflets about CPC), CPC Documentary: Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) – A documentary film highlighting the need of CPC in Maharashtra, Clip-on YouTube – CPC services in Sion Hospital, Media Awareness – Celebrating Children’s Day, programme on IBN Lokmat Marathi News Channel for awareness about CPC and A film ‘Little Star – Taabish’s story’ on Thalassemia.[15]

- Integration analysis matrix.

- Integration analysis matrix.

- Output target compliance matrix.

DISCUSSION

The CPC project was the first of its kind in India, to develop a comprehensive paediatric palliative care programme in Maharashtra, as a model for future implementation in the rest of India. The project was primarily an advocacy project and was designed to improve access to CPC through integration within the healthcare system. Health information was provided through existing channels and formats in the public health system. Funding from DFID UK, collaboration from ICPCN and peer-review process helped to develop and implement the plan efficiently through logical framework project management. The Tata Memorial Centre was chosen for this project due to local expertise availability, and it continues to be one of the champions for the development of CPC in India. The results identify the necessity for tailored and coordinated models of care. Clinicians working with these families need to be alert to the supportive and palliative care needs and ensure that specific needs are addressed early in the illness trajectory. Timely evaluations in the project, as part of the inbuilt monitoring plan, helped in integrating palliative care in the public health system of the state. Maharashtra became the second state in the country to create a palliative care policy to be integrated into the public health system, with an aim of equitable access. Our findings support those of Wolfe et al. that earlier recognition of a child’s prognosis will lead to a stronger emphasis on treatment directed at lessening the suffering and greater integration of palliative care and should be offered to all children with life-threatening or chronic illnesses/disabilities with complex care needs.[16]

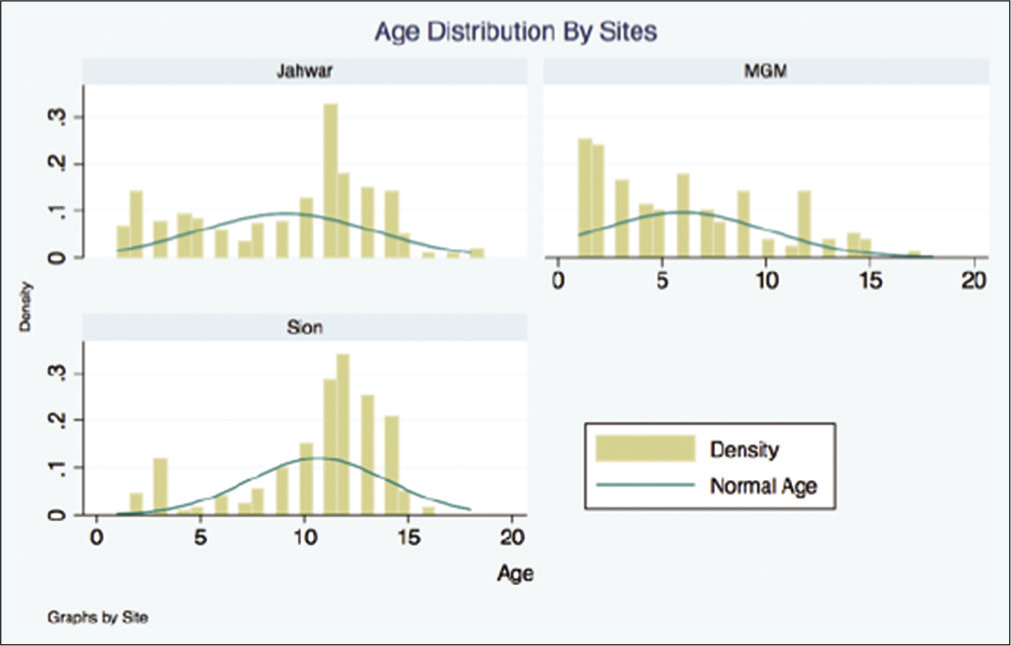

The setting-up of the three project sites was challenging considering the novelty of the project, but in the end, it was intensely rewarding as well to be able to care for children suffering from life-limiting illnesses. The three sites catered for children with different age groups [Figure 6]. At Sion Hospital, for children with HIV, going beyond medicine compliance to holistic care for each child and family, was highly enriching for paediatric healthcare staff working there. The children were able to grapple with the disease and followed up with the unit, all the while helping peers.

- Age distribution by site.

The role of supporting extended families came to the forefront with the grandparents ably taking care of children, whose parents had already succumbed to the disease. In rural Jawhar, the setting-up and response to holistic care in improving outcomes led the government to set up another centre at Igatpuri, a nearby rural health centre. The site at Kalamboli paved the way to start neonatal palliative care in Maharashtra.

The strength of this study lies in the novelty and adaptability of the project to periodical inbuilt reviews. The logical framework model aided in this. Results varied between sites, due to differences in geographical location, socioeconomic status and disease conditions. The Sion site was purely urban, and a well-developed centre for paediatric HIV; the rural site at Jawhar was a remote, hilly area with very few primary health facilities where ASHA workers were the strength of this site. They were the mainstay to identify the patients and bring them to the rural hospital, as well as aid in follow-up. The urban site at Kalamboli allowed a huge catchment area of varying disease types. It was the first centre developed for providing neonatal palliative care and served as a nidus for the future development of neonatal palliative care in India. The project made use of an experiential learning model that was built on the expertise and experience of palliative care experts in the training of health workers and that of TMH as a centre of excellence. The selection of TMH is supported by their experience of providing palliative care. TMH’s Palliative Medicine Department, led by a professor specialising in paediatric malignancies, is renowned in India and is regarded as a centre of excellence in PC provision. The approach provided an opportunity to expose the new sites to the concept of CPC and to what works when applying acquired knowledge through practical learning. Trained health workers felt the training and ‘placement’ at TMH enabled them to have a practical feel of the management of CPC clients. Interviewed health personnel mentioned how this helped them grasp skills for communicating with children and caregivers including breaking bad news, holistic assessments and bereavement counselling. The feedback of trained groups brought to the fore the logic of the process undertaken that is, the three phases: (i) Training of concept (Experts – ICPCN, IAPC and TMH), (ii) build skills through placement and mentorship and (iii) implementation supported by supervision and quality improvement services. There are certain limitations which need careful acknowledgement. The multidimensional design was difficult to implement with the project stakeholders, and at times, it resulted in a loose set of activities which might have limited the project’s potential. The project was holistically applied at all the sites and healthcare outcomes; data were collected in the form of QoL, policy, and training aspects. Greater attention could have also been placed on strengthening the referral mechanisms, establishing a system for quality improvement of healthcare delivery and data capture through electronic medical record system rather than through emails. At times, there was an absence of post-training/placement activities to strategise and develop an operational plan that reflects an adaptation of lessons drawn from the placement at TMH as well as minimal peer exchange among the new sites may have limited the transfer and application of acquired skills in the localised setting.

Current scenario and future strategies

As of 2021, dedicated paediatric palliative care service units have started in Kerala, Delhi, Hyderabad, Chennai, Mumbai, and Manipal. Smaller centres have been set up under the guidance of Tata Memorial Hospital at Goa and Aurangabad, and three more centres in Mumbai have been set up for non-cancer. A few years ago, the Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India, passed an amendment to the ‘ICPS,’ by which children with life-limiting conditions could avail of a monthly stipend, life-long. The ‘Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram’ had also passed a scheme for the early identification of children with life limiting conditions to be identified and rehabilitated.

Other activities include:

A National Strategy for PPC with an involvement of paediatricians and other specialists to maximize resources based on needs analysis,

Networking with NGOs and other voluntary groups,

Inclusion and implementation of CPC into existing health system which is community oriented and sustainable to ensure quality care to all children and their families with life-limiting conditions,

Research in the field of CPC to make it accessible and affordable to all,

Respite services to improve the QoL for children and all other family members (either in-home or residential),

Developing criteria for dedicated home care and children’s hospices for residential or daytime respite wherever feasible.

CONCLUSION

The CPC project was challenging, but a very rewarding experience as well and could fulfil its objectives. The project led to changes in healthcare system in the state of Maharashtra, where a lot of progress has been made in making CPC an integral part of the public health system as well as part of the curriculum and practical training for healthcare professionals. Although there were aspects which were unachievable, the experience should benefit future endeavours.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the project staffs from ICPCN, DFID, Government of Maharashtra, patients and their families.

Data availability statement

Available on request to the corresponding author. Not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of data containing patient details and clinical information.

Data deposition

Available with the corresponding author.

Geolocation information

Maharashtra, India.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

The project is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and is coordinated by the ICPCN and Help the Hospices (UK), with the Tata Memorial Centre providing mentorship.

Conflicts of interest

Arunangshu Ghoshal is a member of the editorial group of IJPC.

References

- Experiences of healthcare, including palliative care, of children with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions and their families: A longitudinal qualitative investigation. Arch Dis Child. 2020;106:570-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home Association for Paediatric Palliative Medicine (APPM) Available from: https://www.appm.org.uk [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- Committee on bioethics and committee on hospital care. Palliative care for children Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 Pt 1):351-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Definition of Palliative Care Geneva: World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/# http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en [Last accessed on 2021, Dec 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Global Atlas on Palliative Care at the End of Life. Available from: http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 09]

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of educational training in improving skills, practice, attitude, and knowledge of healthcare workers in pediatric palliative care: Children's palliative care project in the Indian state of Maharashtra. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:411-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Validity and responsiveness of the pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL) 4. 0 generic core scales in the pediatric inpatient setting. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:1114-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Software India IBM. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/in-en/analytics/spss-statistics-software [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 24]

- [Google Scholar]

- CanShala (School for Cancer Children) CANKIDS KIDSCAN. Available from: http://www.cankidsindia.org/canshala-school-for-cancer-children.html [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 21]

- [Google Scholar]

- Government Policies Pallium India. Available from: https://palliumindia.org/resources/policies [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 25]

- [Google Scholar]

- State Government Comes up with Palliative Care Policy Indian Express. Available from: http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/state-government-comes-up-with-palliative-care-policy/1087167/1 [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 25]

- [Google Scholar]

- India ICPCN. Available from: http://www.icpcn.org/india [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 24]

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: Impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:2469-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Appendix 1: Protocol of Referrals of Children to Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital and Medical College, Sion.

It is an urban centre set up in July 2011 in collaboration with Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital (L.T.M.G.H) to look after children with HIV/AIDS, provide them with psychosocial supportive care, counselling/focus group discussion/training of doctors and outreach workers/activities for children and caregivers).

Appendix 2: Protocol of Referral of Children to Palliative Care, Patangshah Cottage Sub District Hospital, Jawhar.

It was a rural healthcare programme set-up in October 2011 in collaboration with the National Rural Health Mission (N.R.H.M) to mainstream palliative care into the Rural Cottage Hospital and implemented into four primary health centres (PHCs) working at the grassroot level, through liaison with the ASHA workers for identifying and referral of patients. Conditions in children included – cerebral palsy, mental retardation, epilepsy, cancer, malnutrition, HIV, thalassemia and sickle cell. It was designed for

Integration of palliative care into the existing public health systems at grassroot level Training and education of all cadres of health workers To network and strengthen linkages with existing NGO’s, CBO’s for referral of patients Community mobilization To train ASHA’s and ANM’s in Basic Nursing Assessment and Symptom Management to provide palliative care to patients at a basic level

Collaboration with the National Rural Health Mission (N.R.H.M) and structure of CPC implementation

Appendix 3: Protocol of Referral of Children to Palliative Care, Mahatma Gandhi Mission Hospital, Kalamboli.

This programme was set up in March 2013 in collaboration with Mahatma Gandhi Mission Hospital (MGM), Kalamboli. MGM has specialised paediatric and neonatal intensive care units along with an outreach programme. Conditions in children included – cancer, thalassemia, cerebral palsy, congenital heart disease, haemophilia and genetic disorders. Interventions were counselling, focus group discussion, training of doctors and outreach workers and activities for children and caregivers.