Translate this page into:

Stress among Care Givers: The Impact of Nursing a Relative with Cancer

Address for correspondence: Dr. Priyadarshini Kulkarni; E-mail: priyadarshini.kulkarni@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aims:

The aim of the present study is to assess the level and areas of stress among care givers nursing their loved ones suffering from cancer.

Setting and Design:

An assessment of care givers’ stress providing care to cancer patients at Cipla Palliative Care Center was conducted. The study involves data collection using a questionnaire and subsequent analysis.

Materials and Methods:

A close-ended questionnaire that had seven sections on different aspects of caregivers’ stress was developed and administered to 137 participants and purpose of conducting the survey was explained to their understanding. Caregivers who were willing to participate were asked to read and/or explained the questions and requested to reply as per the scales given. Data was collected in the questionnaires and was quantitatively analyzed.

Results:

The study results showed that overall stress level among caregivers is 5.18 ± 0.26 (on a scale of 0-10); of the total, nearly 62% of caregivers were ready to ask for professional help from nurses, medical social workers and counselors to cope up with their stress.

Conclusion:

Stress among caregivers ultimately affects quality of care that is being provided to the patient. This is also because they are unprepared to provide care, have inadequate knowledge about care giving along with financial burden, physical and emotional stress. Thus interventions are needed to help caregivers to strengthen their confidence in giving care and come out with better quality of care.

Keywords

Care giver

Interventions

Palliative care

Quality of life

Stress

INTRODUCTION

Cancer affects the entire family, not just the patient. Treating a cancer patient is often an exercise of treating a part if not the whole family of the patient. Northouse[1] and Brown[2] suggest that in addition to causing distress to the patient, it puts financial, personal, social and health stress on family members. If care givers are among the family, as they usually are, stress reduces the quality of care that the patient receives. The amount and type of stress is culturally determined and needs to be evaluated accurately, if strategies are to be developed to combat it. If the stress of the care givers is reduced, then one can expect the patient to benefit.

Studies on caregiver stress have been conducted, using different tools. How well each of these tools correlate with each other is not known with certainty, nor is it known how these tools will perform in different cultural set-ups like those in our country. In fact, no studies have been conducted on care giver stress in India; hence there is a lack in appreciation of the problem. In the absence of any such data, it is difficult to formulate policies which would support the care givers in this arduous task.

As patients move through the stages of diagnosis, therapy, remission and relapse, their quality of life (QOL) deteriorates steadily, state Girgis et al. (2013).[3] During this, Calman[4] and Patterson et al. (2013)[5] note, daily routines of the family are disrupted, typical duties and activities performed by one member may change or shift onto other family members and there are financial issues. The impact of the disease is higher in a country like ours, state Broom and Doron,[6] where the family and not the state, is the source of all support to the patient and the role played by the family is very crucial.

Palliative care should begin right from the stage of diagnosis, but Smith et al.[7] observe that it rarely is given at this stage. At least in India, palliative care is mostly used in the end-of-life stage. By this time, the disease has consumed both the victim and the family and both are in need of support. Treating the care givers becomes imperative, since stress erodes the quality of support they can give to the patient, as demonstrated by Ekedahl and Wengström[8] , Vrettos et al.[9] Often the disease has severe financial impact on the family that lasts for years after the demise of the patient as shown by Brown et al.[10]

Clearly the burden of the disease on care givers needs to be measured and reduced. This was first quantified by Zarit et al.,[11] who introduced the Zarit Burden Inventory. This scale has undergone revisions and a number of newer instruments have been developed. Some of these are disease specific while others are generic and aimed at exploring the effect of the stress on a particular aspect of the care givers’ life, as shown in a review by Van Durme et al.[12] After a careful study of the available scales we decided to develop our own which will be more suited for conditions prevailing in our country.

At Cipla Palliative Care and Training Center, a premium is placed on family providing the day to day care to the patient. The family member who will be the main care giver is required to stay with the patient in the center and is trained to look after the patient totally. The care giver is trained to manage the nutrition, nursing, dressing and even medical emergencies, in a home setting. The duty thrust upon the care givers often impacts their health and reduces their efficiency in delivering quality care as shown by Ross et al. (2013)[13] and Chang et al (2013).[14] Hence the present investigation was undertaken to identify stressors and quantify their impact.

At our center, patients in need of palliation are routinely admitted as in patients, for a short duration. The admission could be for the management of acute symptoms, titrating drug dosages or management of emergencies. When the caregivers are confident that they will be able to manage the patient at home, the patient is discharged. The patient may be readmitted for similar reasons. Annually around 25-30% of patients are readmitted to the center. This is a survey based study that was conducted on care givers of patients admitted to the center.

The highest number of admissions took place in the year 2011-2012. During these 12 months (from January 2011 to January 2012), a total of 984 patients were admitted to the center. However the population of cancer patients in the city and its surroundings is not known. In order to have adequate statistical power it was determined that a minimum of 96 caregivers must be surveyed to obtain data that would reflect the views of care givers, with 95% confidence limits and an error of 10%. Given the high possibility of unusable data, a sample size of 160 was planned so that even with a 40% drop out we would still be left with a 96 samples. However after deleting incomplete questionnaires we were left with 137, which have been analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A bilingual questionnaire was developed to assess the views of caregivers of patients admitted to the Cipla Center. The caregivers were encouraged to seek clarification from the staff in case of failure to understand a question, but were not influenced to provide any particular answer. The questionnaire had seven sections and each section asked a series of questions. Most questions required answers on a scale of 0-4 while stress and health status was graded on a scale of 1-10. Since no information that would identify the care giver or the patient was collected, it was not considered essential to have an Ethics Committee approval for the study. The questionnaire was structured as follows:

Personal information

This section collected personal information of the care giver namely age, gender, education, employment, family details and place of residence (urban or rural). They were asked their relation with the patient, the duration of care giving, prior experience if any etc.

Financial

The 3 questions of this section enquired about financial impact of the disease and the treatment and the impact of finances on the management of the patient. They were also asked whether they would have preferred a private hospital over our center, finance permitting.

Personal

This section probes the issues that relate to the personal life of the caregiver. The 7 questions were aimed to explore the fears and anxieties of the care givers and their perception about the service they are rendering to the patients.

Entrapment

People involved in the care of a sick individual often perceive entrapment in the situation. The 6 questions of this section try to elicit the views of care givers toward this aspect of patient care. The care giver often finds himself caught in the situation from where he can hardly escape. This leads to the feeling of being entrapped.

Homecare

Admission of patients to the center is principally to prepare them and their care givers for home care of the patients. In the absence of data on the preference of patients of the place for death, we assumed that most patients will prefer to live and finish their last days at home. In this section, the 4 questions probed whether the caregiver was ready and confident of managing the patient at home if discharged from the center and aimed to assess the care givers’ readiness to manage the patients at home.

Health

Caregivers rated their current health status on a 1-10 scale (1 being very healthy).

Areas of stress

Stress for the care givers is multidimensional. It originates from the patients’ disease and condition and gets magnified by other concerns the caregiver may have. The 3 questions of this section probed the stress level on a scale of 1-10 and the different areas of stress.

The questionnaire was administered to 160 care givers of patients admitted to the Cipla Center. After dropping out the incomplete ones, we were left with 137 for analysis. Only one caregiver per patient was interviewed and it was ensured that that caregiver was the primary caregiver. The filled questionnaires were entered in Microsoft Excel and analyzed.

RESULTS

-

Number of responders: 137

-

Mean age of responders: 43.46 ± 1.39 (range: 17-83 years)

-

Gender distribution: 85 Females: 52 Males

-

Relation with patient:

-

Wife 37

-

Daughter 32

-

Mother 10

-

Sister 6

-

Husband 18

-

Son 27

-

Brother 4

-

Father 3

-

-

Urban/Rural breakup: 84 among our responders came from urban areas while 53 came from rural areas

-

Education: Only 132 respondents’ educational data was available and their distribution was as follows:

-

26 of our care givers were uneducated

-

65 of our care givers were minimally educated (primary school)

-

18 care givers had studied up to high school

-

23 care givers were graduates.

-

-

62 of the care givers were employed while 71 were not employed, one had retired and there was no data for three

-

Most care givers came from non-nuclear families and the average number of people in the family was 5.39 ± 0.21

-

There was a very wide disparity in care giving experience, the least being 0.1 month and the maximum being 360 months. Average duration of care giving was 24.02 months (Standard error-3.43 months)

-

Only 50 had previous experience as care givers, 85 had no experience and 2 care givers did not respond

-

65 care givers had some knowledge about the disease while 44 did not have any, 28 respondents provided ambiguous data.

Financial impact

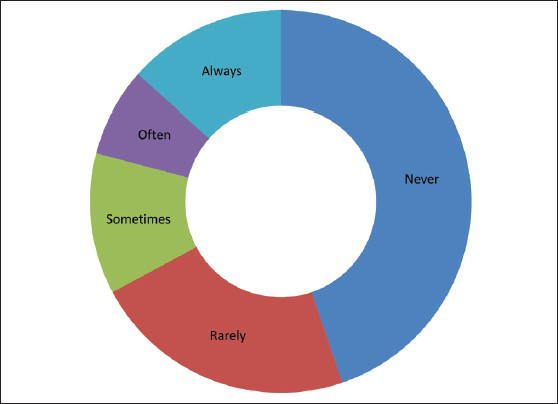

The financial impact of the disease on caregivers is shown in Table 1. Majority of caregivers responded by saying that the disease of their relative did not impact them financially. This result is rather surprising, since most of the care givers were of modest means. Some of the care givers perceived that the shortage of money prevented them from providing private facilities for their relatives, but their proportion was low. One of the reasons could be that the care givers were satisfied with the services provided at the center. This is shown in Figure 1.

- How often did the care givers feel that the shortage of money prevented them from offering care at a private centre for their relatives?

Personal

The responses of caregivers concerning impact on their personal life are given in Table 2. The redeeming feature was that care givers mostly felt that their presence was of use to the patient and they felt needed. An overwhelming proportion of care givers had this positive perception, which probably helps them override many negative perceptions that they have. The results of this are shown in Table 3.

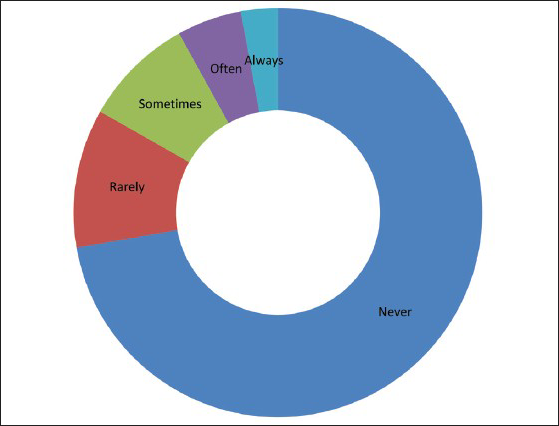

Entrapment

Many care givers feel entrapped due to the situation, however due to the relation with the patient and their intense feeling for the patient, there is very little wish to run away from the situation. There seems to be very little uncertainty about the patient's future, which could be due to the exposure to various programs conducted at the center. The care givers perceive a very high dependence of the patient on them, which is only to be expected. They also feel that the patients cannot be left alone. However on the question whether they feel over whelmed, the response is evenly distributed. The details are given in Table 4 and Figure 2.

- Do you ever feel like running away from the situation?

Family support

Support of the family during crises is of paramount importance. Most care givers felt that they always had the support of the family. They also stated that the family supported the care givers rather than blaming them. This supports the wide spread belief that family ties are very strong in India and the entire family takes an active part in care giving. Very often the caregiver is the target of the patient's anger and the family also blames the care giver, making the person an unfortunate victim of the circumstances. Happily, this did not occur in our case. The care givers’ feeling about family support is given in Table 5.

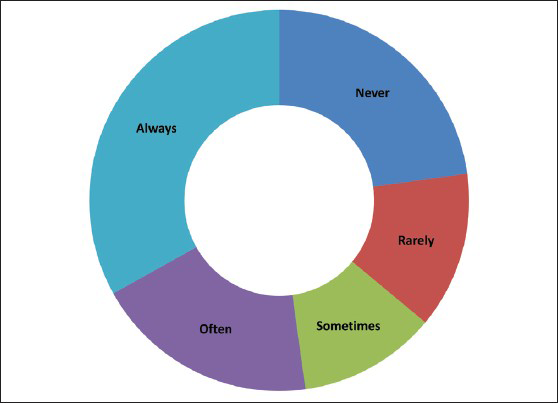

Home care

The care giver's comfort level at caring for the patient at home depends on a variety of factors including easy access to medication, medical personnel, equipment and skill in managing symptoms. A majority of care givers perceived no problem in these areas, yet the comfort level in caring for the patient is not commensurate with these findings. These results are shown in Table 6 and Figure 3.

- Are you comfortable giving care at home?

Health

Stress is likely to lead to tiredness and a reduction in physical health and it does appear to affect some care givers more than others. These parameters are affected among care givers, details are given in Table 7.

Caregivers rated their current health status on a 1-10 scale (1 being very healthy) as: 4.67 ± 0.26

Stress

Current Stress level (1 being least stressed) 5.18 ± 0.26.

Of the respondents, 55 declared that they had other areas of stress while 58 said that they had no other stress. There was no response from 24.

74 of the care givers were open to asking for professional help in case of need, while 45 showed dependence on family only 18 had no response to offer. Current status of the patient's disease was as follows:

-

Patient just diagnosed-1

-

Progressive but patient active-3

-

Disease advanced but patient active-37

-

Disease advanced patient dependent-86

-

Fully bedridden-3.

DISCUSSION

Stress is both a cause and an effect of the disease. In cancer, the disease of the patient causes stress to both the patient and the care giver and this stress may affect the QOL of both. Bevans and Sternberg,[15] suggested that the burden of the disease is perceived to be more by the care givers than the patients themselves. In many cancers, there is a prolonged period of illness and therefore prolonged stress. In this study, the average duration of care has been 24.02 (±3.43) months, the wide variation was due to a few cases succumbing shortly to the disease while a few surviving for long. However, the mean duration of care giving is adequate to induce stress and for all effects of stress to be manifest.

Taking care of a chronically ill patient is not an easy task. It demands a lot of patience, compassion, commitment and kindness, which the patient constantly tests. Patients of chronic disorders very often lose their own patience and start taking out their frustrations on their near and dear ones and the care giver is usually the first person in the line of fire state Bevans and Sternberg.[15] Care givers often ignore or fail to recognize when stress starts to produce physical illness and end up with serious physical and mental illness.

Life in India is highly family oriented. All care givers (without exception) in this study were family members of the patients. Most patients in India cannot hire professional nurses as care givers; hence there is dependence on the family to provide care. The deployment of family member as care givers makes both cultural and economic sense. Chen et al.[16] suggest that familial attachment between the patient and the care giver does not protect the care giver from stress, but at times can actually lead to higher stress. The care givers in our study were from a very wide age range, with an average age of 43.46 ± 1.39 (range: 17-83) years. Most also came from conjugal families with a mean family size being 5.4 (±2.1) members. Allendorf[17] demonstrated that the joint family in India is being replaced with nuclear or conjugal families; this appears to be true among the care givers at our center too.

The most common relation of the care giver to the patient was that of wife, followed by that of daughter. Women dominate over men in the role of care givers with a ratio of 1.6:1, in keeping with the traditional division of labor between sexes. It is only of late that men have entered the field of nursing and midwifery, professions which were hitherto reserved for women only as noted by Brodsky.[18] Females constituted 55.4% while males constituted 44.6% of the care givers, displaying the predominance of women in nursing. The dominance of wives over husbands in care giving is very striking and has been noted elsewhere.[19]

Our center is located in Pune, a Class I city with a population of about 6.11 million (2011 census). It is therefore not surprising that 84 (61.3%) care givers described their home setting as urban while the balance 53 (38.7%) described the setting as rural. Larger families are more common in the rural areas, but conjugal families dominate in the city.

Among our care givers 26 (19.6%) were uneducated, 65 (49.2%) had been educated only up to primary school, whereas 18 (13.6%) had studied high school and 23 (17.4%) had completed their graduation. Almost 47% (62/132) of the care givers were employed while the rest were unemployed.

Most of the care givers (62%) had no previous experience of care giving and half of all care givers had some information about the disease, the level of the knowledge of the others was difficult to evaluate. The reasons why they were giving care to the patient were varied and care givers entered multiple reasons. Love and affection for the patient were quoted as the most common reason for care giving, in some cases family responsibility was cited, as was absence of any other person to take care of the patient.

Cancer being a chronic disease with an unpredictable course, it exacts a high toll from the patient and the family. Treatments of cancer are also very expensive and a case of cancer often means financial ruin of the family as noted by Emanuel et al.[20] It is pitiable that the family after sacrificing everything loses the ailing member too. One often wonders what pushes the family to spend everything that they have trying for a cure. Success stories of patients overcoming cancer are probably the prime movers. Rarely do people realize that examples like those of Kumar[21] are statistical outliers, they do not represent the majority or even the average.

Financial impact

It is self-evident says Kanavos[22] that a chronic disease like cancer would put financial strain on the family of the patient. Yet respondents varied significantly in their answer regarding financial strain. 51 responders said that the disease did not (or rarely) impose a financial burden, while the rest (82) felt that financial sacrifices were required on the part of the family more frequently. Shortage of financial means was felt by about half the respondents, which prevented them from getting their patient treated at a private facility, whereas the other half did not. Their response could also be interpreted to mean that they did not feel the need of taking their patient to a private hospital, as they were satisfied with the care provided at the center.

Personal impact

A majority of care givers were concerned about the patients’ future and they felt that they were not doing enough for the patient. The feeling of the majority of care givers that they did not do enough for the patient and that they wish they could do more, probably stems from the incurable nature of disease. Most of the patients come to this center when therapeutic options have closed and chances of recovery of the patients are very low. For a caregiver, death of the patient is the ultimate failure. We need to focus on this aspect in care giver training, since the loss of a family member causes a guilt complex among the other members. Most of the care givers did not expect that life would take such a turn, which is natural since no one in his or her right senses would expect such a crisis in the family.

Social impact

The disease has been reported to exert a severe social burden all over, but surprisingly we found that most of the caregivers did not feel that their social life has been disrupted because of the disease, nor were they duly worried about the loss of privacy and personal time. The mean score on this point was less than midway (1.35 on a 0-4 scale). The perception about loss of personal time and privacy was also not very high; in fact the score was comparable to that of social life. Social life of the average Indian is highly family oriented and when a near relative is sick, no loss of social life is felt. Such a feeling probably stems from the cultural set up in India and that in this population blood is still thicker than water.

A redeeming feature is the feeling of a majority of care givers that they were needed and their efforts were useful to the patient. This is despite the stress, privations and irritability of the patient. The patient generally takes out all his or her frustrations on the care givers, since they are the persons who are available and ones who would not retaliate. This tells us that care givers need to have some very special skills, along with patience and empathy. The feeling of being needed and wanted, overrides negative feelings that the care giver may have had from time to time.

Entrapment

Most of the caregivers (58%) always felt that the patients were dependent on them and about the same number felt that the patient could never be left alone. Nearly 70% were sure of what is to be done for the patients. The perception of being overwhelmed was not widely felt and the mean score on this count was less than the half way mark. 72% of care givers never thought of running away from the situation and an additional 11% rarely thought about it. Yet there was a small minority of 11 care givers who were totally overwhelmed and wanted to run away from the situation. Special efforts need to be taken to identify these and counsel them rigorously, if we are to improve care giving.

It is possible that care givers said that they did not think of running away from the situation, out of fear of public ridicule. All care givers at the center live together and hence peer pressure could have affected the response. The care givers were told that their identity and responses would be kept confidential, but we know not how many care givers understand the concept of confidentiality in research. This was the first survey of its kind conducted by us among care givers; more studies in subgroups of care givers would be required before one can come to a definite conclusion.

Family support

In our sample, the support of the family was found to be very high and 80% of caregivers were satisfied with the family support they received. It is interesting that an identical number said the family did not hold them responsible for the patients’ health implying that the patient's well-being is the responsibility of the whole family and not just if the main caregiver. The authors would interpret this as a sign of growing maturity of the Indian society but this needs to be confirmed. It also supports the feeling that the more support a person gets, the more confident he/she is.

Though joint families dominate the society in India, there are a significant number of nuclear families too. The strength of the family bond is crumbling slowly in India and in a few decades our society may lose its family centric nature. Our country is probably in the transition stage and this picture may change totally in a few years.

Health impact

The disease has varied impact on the caregiver's health. A large number of caregivers reported feeling continually tired and exhausted (52.17%). Lack of sleep was reported by a sizeable number of care givers (45.98%). Inability to focus and mental confusion were reported by 45.65% care givers. None the less it was observed that about half of the caregivers had adapted themselves to the situation very well, while the other half did not. High levels of stress could negatively impact care giver's health, well-being and on-the-job performance. Caregiver burnout has been demonstrated by Akintola et al.[23] and Johnson et al.[24] have shown increased C-reactive protein levels in caregivers. Buyck et al.[25] have demonstrated an increased risk of heart disease in care givers who had poor health to start with. It would be essential to design a scale to help identify caregivers at risk and support them. Such a step would help both the caregivers and the patients.

There was no report of increased incidence of illness during care giving and when they were asked about their health compared to the previous year's, the overall rating was 4.67 (±0.26). This question was graded from 1 to 10 and 1 meant very healthy while 10 meant very ill. Most caregivers were neither healthier nor sicker than the previous year.

Home care

The paucity of medical support in the Indian community has been often reported by many authors such as Desai et al,[26] Grewal et al.[27] and Jeurkar et al.,[28] yet in our survey the care givers were not unduly worried about the availability of doctors, medical supplies or equipment. This could be because of a variety of reasons. Most caregivers came from in and around the city of Pune where medical care is easily accessible; alternately they could have given up the expectation of recovery of the patient and knew that medicines and medical equipment were not going to make a tremendous difference to the patient's health.

There is much confidence in care givers about home care. A good 52% are comfortable with home care. The possibility that care givers would like to take the patient home, so that their personal responsibility lessens, cannot be discounted. Surveys on patients conducted worldwide show that patients are most comfortable at home and would probably be better off there, as shown by Krieger,[29] but considering the confidence level of the caregivers this may not be the best option for all. This is yet another point for focusing care giver training. With more intensive training those with low confidence could be made competent to manage the patients at home.

Overall stress

Majority of the care givers were aware of the final outcome, none the less their overall stress level was at 5.18 ± 0.26. Stress was measured on a scale of 1-10 with 1 meaning no stress and 10 meaning very stressed out. This stress was certainly induced by the disease, but about half of the caregivers said that this was not the only reason. They had other sources of stress which were adding to their overall misery. A large number (62%) was ready to ask for professional help in managing the patient while over a third (37%) were inclined to turn towards the family for help if needed. Care giver stress can be reduced by providing them training to handle stress, providing physical, mental and spiritual support as shown by Harris et al.[30] and required information as shown by Longacre.[31] Existential behavioral therapy has been suggested by Fegg et al.[32] to exert beneficial effects on distress and QOL of informal caregivers of palliative patients.

The condition of the patients whom these care givers were caring for differed significantly. Although three patients were almost critical, 86 patients had advanced disease and were totally dependent on care givers for survival. Majority of the care givers in our survey were looking after advanced cases of cancer, a job that can be very taxing.

Care of the chronically ill patient is one of the most difficult jobs. Unless the care giver has deep affection for the patient, incentive, family support and adaptability, the patient will not receive quality care. Chronic sickness and pain makes most patients turn cantankerous and impatient, they tend to vent their frustration on those near them and the care giver is the usual victim. It is obvious that most of the care givers are doing a thankless job and the end in all the cases is going to be the death of the patient. To keep on taking care of the patient while knowing what the end will be, requires a very special courage.

In the past focus has been on the patients, it is suggested by Kutner et al.[33] and Mitnick et al.[34] that it is time attention is paid to the woes of the care giver. The care giver needs and deserves all the support that we can give. It is important to remember that caring consumes the care giver, just as the disease consumes the victim. Along with doctors and nurses, care givers form the three pillars of palliative medicine; all the three need to be strengthened.

Despite the battering the family receives, due to disease and death, it stands firm providing support to the its suffering members. Toffler's[35] description of the family as ‘the giant shock absorber of society’ holds good even when a family member is diagnosed with cancer. It is the family that stands behind the patient as the sole supporter and care giver. There is no doubt that the family too suffers along with the patient, it would therefore be in the fitness of things to support the care givers and the family.

There are a few shortcomings to this study. Though most questions were close ended, some had to be open ended and these evoked responses which were not amenable to analysis. Secondly, the general condition of the patients whom the caregivers were tending differed significantly, though the majority was in an advanced stage. A selection of caregivers of patients in a similar general condition might have given more uniform results.

CONCLUSION

This survey has helped us identify the support needs of care givers. With interaction and training many of the problems faced by caregivers can be addressed. A stress free and confident relative would be able to care for the patient more efficiently than one who is stressed out and confused. Confident and competent care givers will relieve the workers at the Palliative care center, for other important responsibilities, improving the overall efficiency of the center. Aeschylus the Greek Philosopher (525-456 BC) said “Count no man happy until his end is known” we need to improve the end of life care, which forms a part of palliative care.

Source of Support: All authors are working with Cipla Palliative Care and Training Center in Pune

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- The impact of cancer on the family: An overview. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1984;14:215-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- The national economic burden of cancer: An update. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1811-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Some things change, some things stay the same: A longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers’ unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1557-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Head and neck cancer and dysphagia; caring for carers. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1815-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traditional medicines, collective negotiation, and representations of risk in Indian cancer care. Qual Health Res. 2013;23:54-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nurses in cancer care : Stress when encountering existential issues. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:228-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparing health-related quality of life of cancer patients under chemotherapy and of their caregivers. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:135-283.

- [Google Scholar]

- The burden of illness of cancer: Economic cost and quality of life. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:91-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20:649-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tools for measuring the impact of informal caregiving of the elderly: A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:490-504.

- [Google Scholar]

- A labor of love: The influence of cancer caregiving on health behaviors. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:474-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burdens, needs and satisfaction of terminal cancer patients and their caregivers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:209-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA. 2012;307:398-403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of attachment quality on caregiving of a parent with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013 In Press

- [Google Scholar]

- Going nuclear. Family structure and young women's health in India, 1992-2006? Demography. 2013;50:853-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spouses’ experience of caregiving for cancer patients: A literature review. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60:178-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economic impact of terminal illness and the willingness to change it. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:941-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- The rising burden of cancer in the developing world. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(Suppl 8):viii15-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceived stress and burnout among volunteer caregivers working in AIDS care in South Africa. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2738-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of the evidence of a relationship between chronic psychosocial stress and C-reactive protein. Mol Diagn Ther. 2013;17:147-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informal caregiving and the risk for coronary heart disease: The Whitehall II study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1316-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human Development in India-Challenges for a society in transition. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inclusive growth in India: Past performance and future prospects. Indian Economic Review. 2011;8:2229-5526.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which hospice patients with cancer are able to die in the setting of their choice? Results of a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2783-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Defining and investigating social disparities in cancer: Critical issues. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:5-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Trouble won’t last always”: Religious coping and meaning in the stress process. Qual Health Res. 2013;23:773-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer caregivers information needs and resource preferences. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:297-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Existential behavioural therapy for informal caregivers of palliative patients: A randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2079-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Support needs of informal hospice caregivers: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:1101-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family caregivers, patients and physicians: Ethical guidance to optimize relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:255-60.

- [Google Scholar]