Translate this page into:

The Correlation Between Perceived Social Support and Illness Uncertainty in People with Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in Iran

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Illness uncertainty is a source of a chronic and pervasive psychological stress for people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) (PLWH), and largely affects their quality of life and the ability to cope with the disease. Based on the uncertainty in illness theory, the social support is one of the illness uncertainty antecedents, and influences the level of uncertainty perceived by patients.

Aim:

To examine uncertainty in PLWH and its correlation with social support in Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional correlational study was conducted with 80 PLWH presenting to AIDS Research Center, Tehran, Iran in 2013. The data collected using illness uncertainty and social support inventories were analyzed through Pearson's correlation coefficient, Spearman's correlation coefficient, and regression analysis.

Results:

The results showed a high level of illness uncertainty in PLWH and a negative significant correlation between perceived social support and illness uncertainty (P = 0.01, r = -0.29).

Conclusion:

Uncertainty is a serious aspect of illness experience in Iranian PLWH. Providing adequate, structured information to patients as well as opportunities to discuss their concerns with other PLWH and receive emotional support from their health care providers may be worthwhile.

Keywords

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Iran

Social support

Uncertainty in illness

INTRODUCTION

During past decades, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) that naturally accompanied death changed into a chronic disease with coping challenges, such as chronic fatigue, complex treatments, and social stigma. Although some patients may be able to cope with mental stresses of the disease, a lot of them have difficulty coping with the disease due to depression, uncertainty, etc.[1] Uncertainty is a chronic and pervasive source of psychological stress for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH). Illness uncertainty appears when patients cannot determine the meaning of illness-related events, and thus, it is considered a major psychological stressor for patients with life-threatening diseases.[23] Various factors, such as complex and changing treatments, ambiguous pattern of symptoms, and fear of being ostracized from the community highlight illness uncertainty.[4]

Although the rate of HIV infection is very low in Iran (about 0.2%), it has an upward trend.[5] Based on recent statistics, 23,902 PLWH were identified in Iran, but the real rate is estimated to be more than 100,000 people. Men and women with HIV/AIDS comprise 91% and 9%, respectively, and needle sharing among drug users has been reported as the most frequent cause of AIDS in Iran.[6]

Patients with chronic diseases, like HIV, continuously and persistently live with uncertainty, which can damage their physical, social, spiritual, mental, and economic dimensions of life and daily activities.[78] Previous studies showed that increased uncertainty correlated with increased stress,[9] increased mood disorders,[10] and reduced quality of life and effectiveness of patients’ coping.[1112]

This study used theory of uncertainty in illness, according to which structure providers like education, healthcare providers, and social support influence uncertainty directly or indirectly.[7] Some studies showed that patients with higher levels of education experienced less uncertainty.[1113] Shannon and Lee (2008) reported a strong inverse correlation between social support and uncertainty in patients with AIDS.[14] Other studies also revealed a significant correlation between social support and uncertainty,[1516] but some other studies did not show such a significant correlation.[17] It seems that social support can create certainty in patients as informing them can reduce uncertainty.[18]

Numerous studies have been done on illness uncertainty mainly in western countries that culturally differ from Iran. Despite the importance of uncertainty in PLWH, no such published study was found in Iran. In this respect, this study was conducted to determine uncertainty in Iranian PLWH and its correlation with social support. This study also examined the correlation between uncertainty and some selected demographic variables (such as age, education, etc.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional correlational study was conductedwith 80 PLWH going to the AIDS Research Center in Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Research board of the center approved this study. Samples were selected using convenience sampling method. Sample size was determined with reference to similar previous studies as 50 people, but we set the sample size as 80. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Age over 18 years, consent to participate, diagnosed HIV/AIDS, ability to read and write in Persian, lack of significant psychiatric disorders, and lack of other important comorbidities. Participants were briefed and enrolled in the study after signing informed consent form.

Instruments

The data were collected using inventories including a demographics form, Mishel's uncertainty in illness scale– adult form (MUIS-A), and the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS). MUIS-A is a valid and reliable instrument used in different studies and languages for numerous diseases.[1920] This instrument has 32 items with 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Its total score ranges from 32 to 160, and higher score means higher uncertainty. MUIS-A has four subscales. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient for the entire instrument, ambiguity subscale (13 items), complexity (7 items), inconsistency (7 items), and unpredictability (5 items) is 0.87, 0.86, 0.81, 0.7, 0.65, respectively.[19] In this study, the Persian version of MUIS-A whose psychometrics was examined on Iranians and had a suitable reliability and validity[21] was used.

Social support was measured using MSPSS form. This instrument consists of 12 items with 7-point Likert scale from very strongly disagree to very strongly agree. Its total score ranges from 12 to 84, and higher score means higher perceived social support. The Persian version of the instrument was used in different studies in Iran and has a suitable reliability and validity.[2223]

Data analysis

The data were analyzed in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 16 software, using Pearson's and Spearman's correlation coefficients. Regression analysis was performed to determine the relative significance of variables in expression of uncertainty variance. Those variables that had a significant correlation with uncertainty were entered into the model.

RESULTS

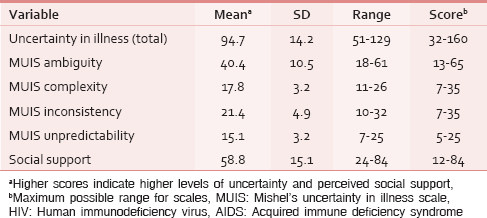

Table 1 shows participants’ demographics and clinical specifications [Table 1]. The results showed participants’ mean total score of uncertainty was 94.7 ± 14.2 (range: 51–129) that indicated a high level of uncertainty in patients. Mean score of the perceived social support was 58.8 ± 15.1 (range: 24–84) [Table 2].

Pearson's correlation test revealed a significant inverse correlation between social support and uncertainty (P = 0.01, r = −0.29). Analysis of data showed a significant inverse correlation between time since diagnosis and uncertainty (P = 0.015, r = −0.27) [Table 3]. Spearman's correlation showed an inverse, though not significant, correlation between education and uncertainty. There was also no significant correlation between other demographic specifications (age, occupation, etc.) and uncertainty.

Regression analysis was used to determine the correlation and predicting value of uncertainty with those of the independent variables. Regression analysis revealed that social support and time since diagnosis expressed 12.3% of the uncertainty variance in patients (P = 0.002, Adj R2 = 0.123). Social support (β = -0.27) and time since diagnosis (β = -0.25) significantly predicted uncertainty.

DISCUSSION

The results showed that PLWH in this study experienced high levels of uncertainty. The results agreed with the level of uncertainty reported in other studies on chronic diseases.[1724] However, mean uncertainty in the present study was somehow higher than that reported in Mishel's combined data for chronic diseases.[19] It can be due to our participants’ lower knowledge than that in western communities.

The results revealed that patients with HIV experienced a medium level of social support. This result agreed with that of a study performed on PLWH in Thailand.[25] Like in other eastern countries, in Iran, family members have a strong and close relationship with one another.

The present study showed a significant inverse correlation between social support and uncertainty (P = 0.01), as patients with higher perceived social support suffered less uncertainty. This result conformed to that of the previous studies on the correlation between uncertainty and social support.[141618] Social support received through public networks, friends, or others makes patients better understand the meaning of events and may increase their ability to clarify uncertain events.[24] This result agreed with that of other studies and the theory of uncertainty in illness.

Similar to the studies conducted by Lasker et al., (2010) and Kang (2011), this study showed no significant correlation between education and uncertainty.[1617] However, some other studies showed a significant correlation between education and uncertainty.[2627] In such studies, education did not have a fixed pattern in correlation with uncertainty; sometimes, the correlation was significant and sometimes not. A possible reason for this finding might be the small sample size because uncertainty score in a small sample shows less difference for the different educational levels and cannot be determined appropriately.

Unlike previous studies, this study did not find a significant correlation between age and uncertainty. Previous studies showed a significant inverse correlation between age and uncertainty, as uncertainty decreased with age.[2829] The lack of significant correlation between these two variables in this study might be due to its rather small sample size and the point that participants’ age was close to one another, which could hide the correlation between age and uncertainty.

The results showed a significant correlation between time since diagnosis and uncertainty, as the patients whose disease was diagnosed before others had less uncertainty. This result also conformed to the theory of uncertainty in illness and was rational because it is clear that patients will be familiar with the disease and its events, and their uncertainty will decrease with the passage of time since diagnosis.

Limitations

Thefirst limitation of this study was its rather small sample size, and the second limitation was related to the convenience sampling method that might have caused sampling bias. Moreover, samples were selected only from the AIDS Research Center in Tehran, and consequently, the results could not be generalized to PLWH in other parts of Iran.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the findings of this study showed that uncertainty is a serious aspect of illness experience in PLWH. Furthermore, the results provided more support in relation to the social support and uncertainty in PLWH. The inverse relationship of social support with uncertainty suggests that providing adequate, structured information to patients, as well as opportunities to discuss their concerns with other PLWH and receive emotional support from their healthcare providers may be worthwhile. The specific nursing strategies for PLWH may include: (a) HIV/AIDS information sheets or pamphlets that explain about the illness (diagnosis procedures, options for treatments, prognosis, etc.), (b) education sessions for newly diagnosed patients and their family members, and (c) support group meetings where newly diagnosed patients can meet other PLWH, share their concerns and form an information network among them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Hereby, we appreciate all patients who intended to participate in our study. The authors express their thanks to the personnel of AIDS Research Center in Tehran and Yarane—Mosbat Club due to their kind cooperation.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- The contribution of adult attachment and perceived social support to depressive symptoms in patients with HIV. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1535-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social support and the management of uncertainty for people living with HIV or AIDS. Health Commun. 2004;16:305-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncertainty in illness across the HIV/AIDS trajectory. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 1998;9:66-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV/AIDS WHOJUNPo. AIDS Epidemic Update. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/islamicrepublicofiran/

- [Google Scholar]

- Iran's Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME). Islamic Republic of Country Report Tehran. Iran: Centre for Disease Management; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theories of uncertainty in illness. In: Smith M, Liehr P, eds. Middle Range Theory for Nursing (3rd ed). New York: Springer; 2013. p. :53-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coming to terms with a diagnosis of HIV in Iran: A phenomenological study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:249-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationships between uncertainty and posttraumatic stress in survivors of childhood cancer. J Nurs Res. 2006;14:133-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Mishel's uncertainty in illness scale-brain tumor form (MUIS-BT) J Neurooncol. 2012;110:293-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncertainty and psychological adjustment in patients with lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1396-401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Illness uncertainty and quality of life of patients with small renal tumors undergoing watchful waiting: A 2-year prospective study. Eur Urol. 2013;63:1122-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- PROSTQA Consortium Study Group. Uncertainty and perception of danger among patients undergoing treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013;111:E84-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV-infected mothers’ perceptions of uncertainty, stress, depression and social support during HIV viral testing of their infants. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:259-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of a conceptual model based on Mishel's theories of uncertainty in illness in a sample of Taiwanese parents of children with cancer: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1510-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationships between uncertainty and its antecedents in Korean patients with atrial fibrillation. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1880-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncertainty and liver transplantation: Women with primary biliary cirrhosis before and after transplant. Women Health. 2010;50:359-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of HIV counselling and testing, self-disclosure, social support and sexual behaviour change among a rural sample of HIV reactive patients in South Africa. Curationis. 2005;28:29-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring illness uncertainty in men undergoing active surveillance for prostate cancer. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24:193-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the mishel's uncertainty in illness scale in patients with Cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:52-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychometric properties of the persian version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in iran. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1277-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncertainty, symptoms, and quality of life in persons with chronic hepatitis C. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:138-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing quality of life among people living with HIV (PLWH) in Suphanburi Province, Thailand. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23:63-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informational needs, health locus of control and uncertainty among women hospitalized with gynecological diseases. Chang Gung Med J. 2005;28:559-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Finding more meaning: The antecedents of uncertainty revisited. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:863-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Testing a model of symptoms, communication, uncertainty, and well-being, in older breast cancer survivors. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:18-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age-related differences in worry and related processes. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2008;66:283-305.

- [Google Scholar]